|

EBEY'S LANDING

Ebey's Landing National Historical Reserve Reading the Cultural Landscape |

|

LANDSCAPE DEVELOPMENT AND SETTLEMENT PATTERNS

Introduction to Settlement Patterns

As a way of understanding historic trends and significant landscape elements on the reserve, it is valuable to trace the patterns of settlement, types of land use, and the structures that reflect human use and adaption to the natural environment over time.

Previous studies (see bibliography) have identified five general historic periods and themes on the reserve including: The Salish Occupation, 1300-1850; White Settlement, 1850-1870; Community Development, 1870-1910; Community Stabilization, 1910-1940; Tourism and Recreation, 1940-present.

While these "eras" are general and the historic themes frequently overlap from one period to another, such an organization provides a framework for understanding the human impacts, artifacts and historic remnants on the landscape we see today. The following is not, therefore, a chronology of events so much as a history of land patterns and significant pieces of the past that still remain in the landscape of the reserve.

The Salish 1300-1850

More than 500 years before white settlement, the Skagit, Snohomish, Kikalos, and Clallam tribes occupied the land and shared the resources of Central Whidbey Island. Attracted to the inland waters and low sandy beaches that made canoe landing safe, the Skagit established three permanent settlements along the shores of Penn Cove. Although different in size, these villages were sited on extended points of land with the largest at Snakelum Point, one on Long Point, and one across the cove at Monroe's Landing.

The Skagit were not a nomadic tribe, but populations in the villages could fluctuate dramatically according to seasonal supplies of fish and game and the harvest of camus and fern which provided their primary diet. In gathering their food crops the Skagit generally lived within the natural balance of the island's food resources. They did, however, practice field burning to enhance the production of camus, bracken fern and nettles which were not naturally abundant in the prairies. Their agricultural practices also included transplanting plant materials to increase production, mulching their crops with organic matter to increase fertility, and cultivating crops like wild carrot and lily by dividing the roots and bulbs.

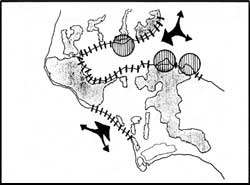

Early Indian settlements along the shores of Penn Cove.

These land practices, though rather contained, altered the native plant communities of Central Whidbey over time. When the Hudson's Bay Company introduced the potato for cultivation in the early 1800s, several tribes tested the agricultural potential of the prairies around Penn Cove. Their great success signaled what was to become a significant and permanent change, the transformation of the prairies into permanent crop-producing lands.

|

|

|

Early Settlement 1850-1870

The white settlers who came to Central Whidbey in the mid-1800s were primarily farmers and merchants. Taking advantage of the Donation Land Claim law, many claimed the rich prairies and shore areas of Penn Cove. Because the claims were made before land surveyors reached the territory, property boundaries often followed natural land forms or a neighbor's claim. The Ebeys, Engles, Crocketts, Kineths, Smiths, Terrys, and Hills settled next to one another on claims that varied in size and shape, each extending to a ridge or woodlot. Virtually all the prairie lands of Central Whidbey were claimed by 1853. These claims meshed together to form major clusters of settlement and it is within these collective boundaries that the structure of white settlement occurred.

Primary access to Central Whidbey occurred along the west shore of the island near Ebey's Landing. Travelers and settlers landed there and moved overland, often stopping at the Ferry house which served over the years as an inn, tavern, mail station and freight depot. Those not staying traveled on to Coveland, where a trading post provided supplies to those individuals leaving for other island communities via Penn Cove. Early roads developed along property lines and followed natural boundaries. By 1855 four roads connected Coveland, Ebey's Prairie, Snakelum Point and other points north.

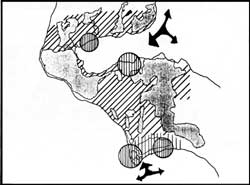

Early homes and newly planted orchards in the open lands around Coupeville.

Most farmers who settled on the prairies of Central Whidbey considered native plants (bracken fern, camus, nettle) weeds that impaired the growth of "valuable" market crops such as wheat, oats, barley, corn, peas and cabbage. Almost immediately they set about improving the prairie fields. They laboriously dug through the root masses of bracken fern using oxen simple plows and hand tools. They built worm fences to enclose domestic livestock and separate cultivated lands from "wilderness". Although the work was difficult and slow, an 1860 census reported 74 established farms clustered in the prairies of Central Whidbey and nearly 1500 acres of improved farm land in Ebey's Prairie and the San de Fuca area.

|

|

|

|

Slowly over the years the population increased and early scattered settlement began to take the shape of a community. As farms began to produce crops for market, the development of ports and service-oriented facilities like blacksmiths and trading posts remained concentrated around Penn Cove, especially at Coveland and Coupeville. The primary economic activity remained agriculture into the 1870s. Even twenty years after claims were made in the prairies, eight of nine original families were still living on Ebey's Prairie and six of nine original families still farmed the lands around San de Fuca.

View of the Ferry House (1865) looking southeast from Ebey's Landing Road.

Community Development 1870-1910

Some early farms on Central Whidbey prospered over the next few years due primarily to productive agricultural soils, improving farm technologies and the skill of the farmer. Several others were not as fortunate and some original donation land claims were broken into smaller properties. Settlers arriving after 1860 claimed upland areas and tried farming in newly-cleared forest lands. Not many of these efforts were profitable and most turned to tenant and subsistence farming.

While land use patterns in the prairies continued to follow the early settlement patterns, farmers also were experimenting in search of a stable market crop. Their success brought more activity and, in response, the town of Coupeville grew into the dominant port and commercial center for the region. By 1881 Coupeville had hardware stores, drug stores, hotels, saloons, a blacksmith shop, courthouse, school, post office and church. Coupeville's growth was based on providing services to the farming community and exporting local goods. In contrast, during the 1880s three other towns were planned, based largely on speculation. Chicago and Brooklyn along Keystone Spit and San de Fuca along Penn Cove all developed as "boom towns" in a flurry of highly-speculative growth. While all three were platted and some developed hotels, saloons and residential areas, none survived as a viable town into the twentieth century.

View of Front Street in Coupeville (c.1900) looking east.

Another major impact on settlement patterns on Central Whidbey near the turn of the century occurred as the military began construction of Fort Casey on Admiralty Head. Requiring large amounts of materials and resources, the Fort included-wharfs and docks, roads, a variety of buildings and several gun emplacements. This significant effort had both immediate and long-range impacts on the physical landscape and social fabric of Central Whidbey. Many acres of forest lands were cut and large volumes of earth moved in the construction of the facility. Keystone became a major wharf drawing traffic to it and affecting transportation networks over the entire island.

Officers' Row (ca. 1905) looking north from the

barracks at Fort Casey on Admiralty Head. Many of these structures

remain as do the parade grounds in the foreground.

By the early twentieth century the landscape of Central Whidbey--the buildings, fields, towns and military structures--reflected a complex of interrelated events, trends and physical change that in a very real sense, carried human history into the fabric of the land itself.

|

|

|

Tourism and Recreation 1910-Present

The community of Central Whidbey Island remained relatively stable over the next several years. Coupeville's growth was gradual, with new residential neighborhoods and Prairie Center spreading the city south and east.

Agriculture continued to dominate land use in the prairies. In San de Fuca however, soils could not withstand intensive crop production and many farmers switched to less intensive feed crops and pasture lands. Two new trends, tourism and recreation, brought new changes to the landscape, just as they continue to influence the economy and physical development of the reserve today.

Construction of the Whid-Isle Inn (1901) on Penn Cove and boathouses at Good Beach signaled an early interest in recreation, focusing around Penn Cove. The increasing number of second or vacation homes around Penn Cove today reflects the continued impact of that trend today. Additional housing needs created by numbers of military personnel stationed to the north in Oak Harbor, brought subdivision of lands in Coupeville, San de Fuca and on the ridge east of Crockett Prairie beginning in the 1950s. Also by 1950 the military complex at Fort Casey, which never saw action, was placed on caretaker status. Several military buildings were sold and moved from the complex to properties outside the reservation and used for other purposes. Their presence marks yet another era in the development of the landscape of the reserve.

The Captain Whidbey Inn, formally the Whid-Isle Inn

on Penn Cove continues as a popular resort today.

In addition to the buildings brought by both tourism and the military, new transportation networks developed and old ones strengthened. Regular ferry service connecting south Whidbey Island to the mainland began in the 1920s. The island's major overland route along Highway 20 took travelers north, and in 1935, the opening of the Deception Pass Bridge assured easy access to the north end of the island. These improved circulation networks, coupled with the establishment of the Naval Air Station, boosted the local economy and after forty years of relatively little growth, the permanent population of Coupeville doubled in the ten years between 1950 and 1960.

|

|

|

|

Ferry landing at Keystone, linking the island with

the Olympic Peninsula.

Cover | Preface | Introduction

Landscape Development and Settlement Patterns

Looking at Landscapes | Reading the Landscape | Preservation Principles

Appendix | Bibliography

rcl/rcl3.htm

Last Updated: 07-Dec-2015