|

EBEY'S LANDING

Ebey's Landing National Historical Reserve Reading the Cultural Landscape |

|

LOOKING AT LANDSCAPES

Introduction to Natural Features

Looking at landscapes involves identifying the individual elements and resources that taken together, create the whole landscape. Natural features such as landforms, soil types and vegetation form the physical parameters within which the built landscape develops.

The built landscape, based on human adaption to the natural environment and use of available resources, is reflected in the types of land use, style and function of structures, and systems of transportation.

When we look at our surroundings, we do not always see these elements so singularly. Often however, identifying each as a specific resource in the context of the whole landscape enhances our understanding of the relationships among these elements, and enriches our understanding of a place and its history.

Formed by geological processes, the various natural resources of a landscape develop over many years. From the earliest shaping of physical land forms to the formation of soils and the establishment of vegetation patterns, these kinds of resources can have a strong influence on settlement patterns and on the physical development of a community over time.

Other reports provide comprehensive inventories of the reserve's natural resources (see bibliography). The following summary considers a few specific resources as they developed and influenced settlement patterns on the reserve.

Evolution of Landforms

Major landforms of the reserve, including the ridges, uplands, prairies and shorelines, formed as the Vashon Glacier began receding 13,000 years ago. The glacier scraped, carved and deposited the islands of Puget Sound as it retreated northward over Washington State.

On Whidbey, the largest island, huge slabs of ice broke away from the main lobes of the glacier and formed giant lake beds. Slowly, as the climate warmed, the water receded and glacial deposits mixed with organic matter to form rich loamy soils in these former lake beds. Today the former lake beds are the prairies of Central Whidbey Island.

In other places, deposits and glacial till collected and formed upland areas and ridges, rarely exceeding 300 feet above sea level. Vegetation on the island established quickly around low-lying marshes and bogs. Highly adaptive and prolific pine tree communities were the first to establish. Slowly, over thousands of years, changing climate and ecological succession replaced pine with fir, spruce, alder, ash and maple. This forest cover remained the primary plant community on central Whidbey until human occupation, some 10,000 years ago, began the equally-slow alteration of the natural environment.

Soils

Soil is a living and constantly changing material formed over many years and influenced by such things as topography, parent material and climate. Each individual soil has distinctive inherent properties that define its potential hazards, its limitations for development, and its qualities as a useful resource. The focus here is on soil as a natural resource specifically related to agricultural land use on the reserve.

On the reserve there is a strong correlation between historic land use and current agricultural capability of soils located on the reserve. Two large areas of extremely fertile soils are located in Ebey's and Crockett prairies, which are the most productive agricultural lands, on the entire island. It is important to note that in all of Island County, only a small portion of the total land mass is comprised of such rich soil and in the entire county, nearly half of that soil is found on the reserve. In addition to this prime resource, the majority of remaining area on the reserve is dominated by a variety of soils which, as a group, are suitable for agriculture with proper management.

Vegetation

As a resource, vegetation on the reserve can best be understood by identifying primary communities as they influenced land use over time. The location and composition of these plant communities can also reflect various impacts and influences as a result of human settlement. Four primary plant communities on the reserve include: beach vegetation, salt marsh vegetation, forest vegetation, and cultural vegetation.

Forest Vegetation

Looking east over the dense forest which covers the narrow neck of

Whidbey Island. The forest extends from the west shore to Penn Cove,

pictured here.

There are no old-growth or original forests on the reserve but there are areas where no cutting or burning has occurred since 1900 and where mature Douglas fir, grand fir and western hemlock can be found. The primary forest cover naturally occurs along the ridges and upland areas of the reserve. Forest cover ranges from very dense and inaccessible to relatively small woodlots interspersed with pasture areas or croplands. The original dense forests on the reserve forced early settlers into naturally open areas, primarily because clearing such large trees involved not only great physical effort, but required valuable time away from crop production in already cleared lands, an activity essential to survival.

Dominant forest vegetation includes Douglas fir, western red cedar, red alder, western hemlock, and occasional madrona and bigleaf maple. Primary understory, or smaller plants, includes elderberry, rhododendron, snowberry, willow, oceanspray, Oregon grape, salal and fern.

Salt Marsh and Beach Vegetation

Fragile beach bluff and Perego's Lake, looking south from Fort Ebey State Park.

Significant salt marsh areas are located at Crockett Lake, Peregos Lake and Grasser's Lagoon. These natural lowland areas provide food and habitat for a variety of bird species and small mammals. Salt marsh plant communities also create seams or ecotones between different habitats which enhance the diversity of both plants and animals.

Historically, all three marsh areas restricted development. They were, nevertheless, subject to a variety of cultural impacts including grazing, cultivation, and recreation activities, which partially altered the native plant communities.

Primary plant species associated with salt marshes on the reserve include pickleweed, saltgrass and saltbrush.

Beach and associated bluff vegetation occurs primarily along the eight-mile western shore of the reserve and along Penn Cove. In addition to routine disturbance by winds and tides, human use over many years has impacted native plant areas, leaving a variety of non-native species. This is especially evident in the public access areas around Penn Cove, and along the west shore of the reserve at Ebey's Landing. Some native plants have survived in less accessible areas, such as in areas around Perego's Lake and protected bluff areas. Historically, the unstable nature of the bluffs along the west coast restricted development and left the area covered primarily by native vegetation.

Primary plants in beach communities include: orchard grass, creeping bentgrass, dune wildrye, velvet grass, yarrow and sand verbena. Primary bluff species include: wild rose, snowberry, bracken fern, orchard grass, blue grass, pea vine, yarrow and seaside plantain.

Cultural Vegetation

Cultural vegetation (or plant communities introduced by humans) occurs in areas where human impact is most evident, primarily in the prairies and upland pastures. Cultural practices, including the introduction of non-native crops, field burning, plowing, grazing domestic livestock, and logging, inevitably and permanently altered original vegetative communities. The current plant cover reflects these practices and disturbances not only in the prairies, but in adjacent lands where the spread of weeds and pasture grasses impacted areas of native vegetation.

Another product of cultural practices over time resulted in a large number of hedgerows on the reserve. Developing along former fence lines, hedgerows are valuable ecological resources in the rural landscape. Although they take many years to develop naturally, once established they can favorably influence micro-climate, minimize soil erosion, conserve soil moisture and provide wildlife habitat, which in turn can increase soil fertility and restrict the growth of undesirable weeds. Most of the hedgerows on the reserve are the result of birds perching on fences and either dropping berries or scratching in the nearby soil accidently planting seeds. With care, hedges can be encouraged to grow to usefulness "in the time it takes for a fence to fall in disrepair" (del Moral, 1980).

Primary vegetation in open areas includes various commercial crops in cultivated fields, as well as Canadian thistle, pickly lettuce, goldenrod, nettle, quackgrass, yarrow, brome, bluegrass and perennial ryegrass.

Primary vegetation along hedgerows includes nootka rose, snowberry, bracken fern and Himalayan blackberry.

Introduction to the Built Landscape

The built landscape is represented by those features and patterns reflecting human occupation and use of natural resources. Virtually every landscape we see is, to some degree, impacted this way. Clearing or planting vegetation, building homes, fencing crop lands or pastures, establishing political boundaries and transportation networks and other activities, all reflect human manipulation of the natural landscape. Over time, community values, social tastes, or basic needs may change, but frequently, as on the reserve, built elements in the landscape survive as characteristics or reminders of a particular historic era or cultural trend.

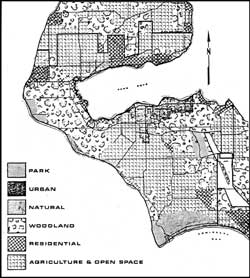

Land Use

In response to natural resources, economic conditions and community development, land use on the reserve today reflects the evolution of activities and land use patterns from early settlement. These primary and consistent patterns include: agricultural use of the prairies, concentration of service and commercial development around Coupeville and the maintenance of natural areas (woodlands and forests) on the ridges and upland areas. While new development is occurring and land uses are changing in specific areas, these broad land use systems represent historic patterns and reflect continuity of use based on the inherent qualities of the natural landscape. This is particularly evident in the consistent agricultural use of the prairies and the stability of Coupeville.

Coupeville

Coupeville includes 740 acres of land, and remains, as it has since established in 1881, the governmental and commercial center of the reserve.

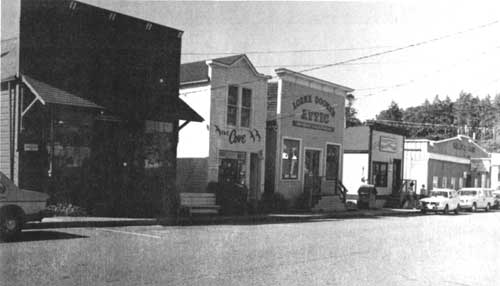

First developing along Front Street on the waterfront of Penn Cove, the town has a strong cohesive structure. This is due, in part, to the number of false front commercial structures along Front Street and the close proximity of residential neighborhoods (relative to the town).

The dominance of false front buildings along Front

Street contribute to the visual and structural unity of the town.

Prairie Center developed at the turn of the century and, although never competing with Front Street in terms of services, it did develop services that helped pull development in the town toward the south. In more recent years, the linear area along Main Street, linking Prairie Center, with Front Street, developed an importance of its own. Main Street became the primary entry to the historic waterfront when Highway 20 replaced the old entry along Penn Cove. Several government buildings, small shops, and stores located along Main Street, and the area became a district of its own. In the areas around these primary service districts, residential neighborhoods filled-in close to this commercial development and in some ways helped contain the spread of new commercial structures. These neighborhoods retain a cohesive character with a number of pre-1900 residential structures remaining on their original city lots. Newer residential development is primarily occurring in clustered developments around Penn Cove and the upland areas surrounding Coupeville, reflecting an influx of permanent and seasonal populations.

Agriculture

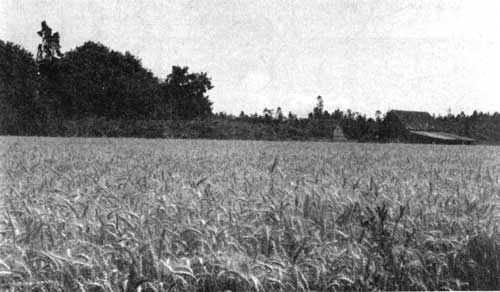

Cultivated fields, pastures, woodlands and open space comprise the majority of lands on the reserve (nearly 90 percent) Agriculture remains viable largely because of the rich soils (see previous section), low rainfall and relatively warm annual temperatures. A survey (see Comprehensive Plan, 1980) indicated the reserve has 48 working farms ranging in size from five to seven hundred acres. Altogether these farms cover approximately 6,000 acres of agricultural land and of that 6000 acres, 3,500 acres is in cropland.

Along with Ebey's Prairie pictured below, Crockett

Prairie contains some of the richest agricultural soils in the entire

county.

Land leasing, a practice similar to historic farming practices where farm land is worked by non-owners, is still practiced on the reserve. In some cases, several generations of a single family continue in the farming community and, despite the relative difficulty of small scale farming and competitive markets, the current farm community appears committed to maintaining productive prairie lands in agricultural use.

Structures

Like land use, structures are a response to both individual needs and the inherent qualities and specific resources of the landscape. Building type, location, materials, details, location, function, and siting reflect cultural customs, economic conditions, technology, and a basic relationship between human need and the natural environment. Whether on a south-facing ridge or along the road into Coupeville, many structures on the reserve reflect these adaptations and a number of them survive as significant historic and cultural resources.

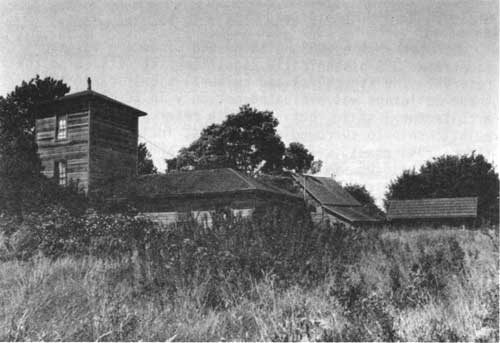

Historic buildings like this farm complex in Ebey's

Prairie (above) and this residence (below) were recorded in the 1983

Inventory of the reserve.

In 1983, all structures on the reserve built before 1940 were surveyed and the historic significance of each evaluated according to National Register criteria (see bibliography). Based on that work and additional field work, structures on the reserve can be defined as. below-ground, which primarily includes archeological sites, and above-ground structures which can be broken into three categories: historic buildings, including barns and residences, transportation-related structures such as roads and docks, and remnant and small-scale structures like fences, walls, or road markers.

Historic Buildings

Altogether the 1983 Building and Landscape Inventory identified 338 historically significant structures on the reserve. The structural and cultural significance of these buildings was evaluated not only in terms of architectural style, but also with reference to their relationship to surrounding elements, including other structures, roads, vegetation, water, and topography. Primary building styles range from the simple saltbox to the more ornate Victorian residence and the twentieth-century bungalow. Although no single style dominates the building character of the reserve, there is a cohesiveness among the various structures. Many buildings throughout. the reserve are constructed of wood with clapboard or shiplap siding, and the colors, lines, materials, details, and construction techniques create a sense of locale and visual continuity.

One hundred and seventy-seven historically significant buildings are located in Coupeville alone, including most of the false front commercial buildings and a variety of significant residential structures. Many of these older homes are located on early platted city lots with original walks, gates, orchards, or gardens still intact. The proximity of historic buildings to newer residences and structures adds a dimension of time and richness to the community landscape.

In the outlying areas, several historic buildings, primarily residences and farm buildings, are located along the earliest roads and sited in response to the natural contour of the land. Many farm complexes with a main residence, a barn and several outbuildings, remain as examples of farm building practices over several generations. The viability of these buildings throughout the reserve and their continued function as useful structures adds a valuable dimension to the landscape we see.

Transportation-Related Structures

A number of significant roadways, wharfs and docks, bridges, paths and foot trails still remain as remnants or working structures within the reserve.

Primary vehicular access to the reserve is along Highway 20 and Highway 525. These relatively recent roadways connect to a compact system of secondary roads, many of which are based on the earliest roads established on the reserve. Roads from Ebey's Landing into the Prairie Center area (1865), Coupeville to Coveland (1853), Ebey's Prairie to Smith Prairie (1854) and Keystone to the Prairie Center area (1874) are examples of this network.

Associated with these roads are a number of internal farm roads and pathways that have remained patterns of movement for over a century. The remnants of a wagon bridge once linking Keystone with Crockett Prairie remain in the marshy waters of Crockett Lake. That same road (1874) traveled overland to Prairie Center along what is now Fort Casey Road.

The early dominance of water transportation is evidenced in the remains of several wharfs and docks on the waters of the reserve. Two docks at San de Fuca and the large wharf and dock at Coupeville (1905) reflect the significance of areas around Penn Cove as ports for market goods and travelers. The oldest extant wharf and dock (1898) is located near Keystone and was used by the military during construction of Fort Casey.

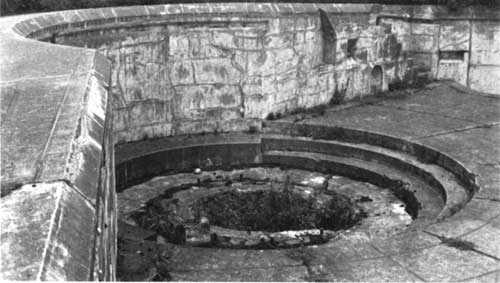

Remains of the military wharf and dock (1898) along Keystone Spit.

Other Structures and Small-Scale Elements

Other significant above-ground structures include military emplacements, blockhouses, th.e cemetery, and smaller elements such as walls, fences, wells, and irrigation structures.

Abandoned gun emplacements are located along the west shoreline of the reserve. Collectively, they represent the military presence on the reserve and have interpretive value as well as sculptural quality.

Gun emplacement along the west shore of the reserve.

Four blockhouses built by early settlers to protect them from the Indians are located on the reserve. Although never used for defense, the physical presence, similar materials and construction techniques and, in some cases, original location of these structures are significant.

The pioneer cemetery, located on a ridge overlooking Ebey's Prairie, was officially deeded in 1869, and named Sunnyside after Jacob Ebey's farm. The oldest sections of the cemetery contain Ebey, Crockett, and Kellogg graves, as well as several other pioneers of Central Whidbey. Generally, monuments and markers face east and, while some fragile wooden markers remain, most of the monuments are stone.

The markers in a cemetery and fence

details can help define a unique sense of place.

Fences, walls and other small structures built on the landscape can express technical capability, as well as conventions or styles of a period. Equally significant, these small aspects of the landscape may also express the personality and spirit of a place, showing individual innovations and even whimsy. When they reflect historic systems and patterns, or express its spirit they are significant resources for understanding cultural history in the landscape.

In many places old and abandoned farm

machinery, tools and various kinds of equipment

like this scale remain

on the landscape of the reserve.

Below-Ground Structures

Below-ground structures are primarily represented by archeological sites. Archeological sites can provide information ranging from the identification of a resource found in a specific place to the physical activities of a culture interacting with these resources. The development of technologies land uses, and even the relationship to larger cultural trends and behavior patterns can often be understood by studying archeological sites. Thirty-five known archeological sites are located on the reserve. Archeological work on the reserve was conducted in the 1950s and reviewed again in 1983 (see bibliography).

Indian long boat in Coupeville.

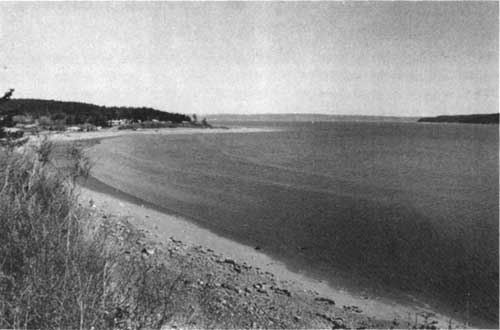

Findings from the initial work indicate that with the exception of one site on Ebey's Prairie and four sites on the upland ridges around Penn Cove, all remaining (known) sites are located in the littoral environment of Penn Cove. Most of these sites are high density artifact clusters. Since little information exists on the distribution of other sites, it is not possible to evaluate the relationship among sites or ascertain details of prehistoric settlement patterns or land uses (Harris, 1983). Lack of information does not pre-empt the significance of known or potential archeological sites on the reserve.

Quiet inland waters of Penn Cove used by the Indians of Central Whidbey.

Landscape Development and Settlement Patterns | Looking at Landscapes | Reading the Landscape

Preservation Principles | Appendix | Bibliography

rcl/rcl4.htm

Last Updated: 07-Dec-2015