|

Haleakala National Park Hawai'i |

|

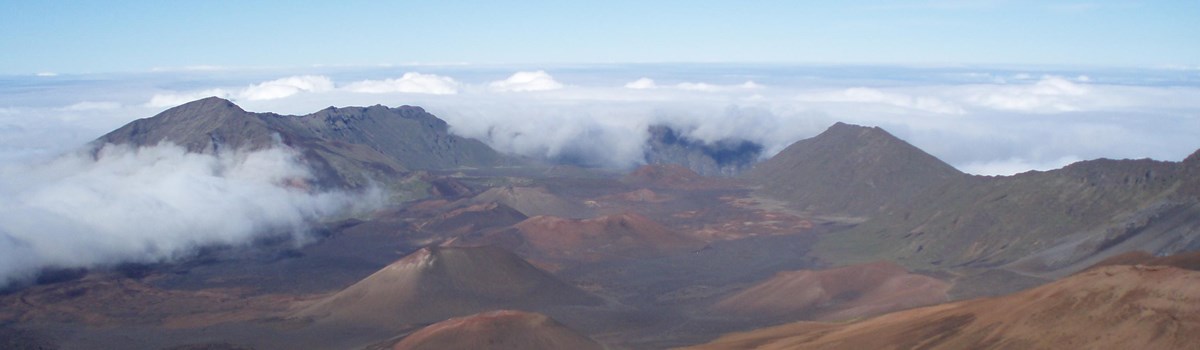

NPS photo | |

The most isolated major island group on Earth, the Hawaiian archipelago is 2,400 miles from the nearest continent. The chain reaches from the Big Island of Hawaii (at about the same latitude as Mexico City) to Kure Atoll 1,500 miles to the northwest, and it is still growing. For at least 81 million years, new islands have been forming as the Pacific Plate moves northwestward over a stationary plume of magma rising from a "hot spot" within the Earth's mantle. The fluid rock makes its way up through the ocean floor, and countless eruptions over hundreds of thousands of years eventually create a volcanic island. But the plate's unceasing movement slowly separates the volcano from its source, terminating its growth even as a new volcano rises from the ocean floor over the hot spot. The volcano that formed East Maui, part of which lies within the boundaries of the national park, last erupted about two centuries ago.

Across vast expanses of ocean, life eventually came to Maui and the other islands in the form of seeds, spores, insects, spiders, birds, and small plants. They drifted on the wind, floated on ocean currents, or hitched a ride on migrating or storm-driven birds. Many groups of organisms (amphibians, reptiles, social insects, and all land mammals except earlier ancestors of the monk seal and of bats) were unable to make the long journey, while some arrived but did not survive in their new home. It is estimated that an average of only one species every 35,000 years successfully colonized the islands. The survivors found themselves in a land of vast opportunity. The Hawaiian Islands are a mosaic of habitats, from rain forest to alpine, often in close proximity. In the surrounding ocean, rainfall averages 25-30 inches annually. Yet Maui and the other islands, trapping moist trade winds, receive rainfall ranging from over 400 inches annually on the windward side of the mountains to less than 10 inches on the leeward side. Average temperatures range from 75°F at sea level to 40°F at the summit of the highest volcanoes. Isolated by the sea, these mountains have created an extremely diverse environment in a small area.

The colonizers gradually adapted to the environment of the islands and to life without the predators and competitors of their homelands. Eventually most evolved into entirely new (and often defenseless) species found nowhere else in the world. The roughly 10,000 native species of flora and fauna of the Hawaiian Islands are thought to have evolved from about 2,000 colonizing ancestral species. The isolation that has made the plants and animals of the Hawaiian Islands unique also makes them vulnerable to rapid changes brought on by humans. Hawaiian species often cope poorly with habitat alterations, foreign diseases, predation, and competition from introduced species. (Today about 20 alien species are introduced to the islands every year.) Active intervention by conservation managers is essential to the survival of the natural heritage of Hawaii.

The distinctive cinder cones that dot the summit landscape of Haleakalā resulted from relatively recent eruptions. Material from these mildly explosive, fountaining eruptions settled back around the vent forming the cones. Only a few plants, birds, and insects have adapted to the harsh conditions created at the summit and on the upper slopes of the volcano. 'Ahinahina (silverswords) have shallow root systems that allow them to catch moisture in the porous, loose cinders and long tap roots that anchor the plants in high wind. The dense covering of silvery hairs on the leaves helps conserve moisture and protect the plants from the intense, high-elevation sun.

By adapting to a variety of food sources and habitats through the process of adaptive radiation, a single finch-like ancestor from the Americas gave rise to an estimated 52 species of Hawaiian honeycreepers. The slightly curved bill of the 'akohekohe is ideal for feeding on the nectar of native flowers. Strategies for feeding on insects resulted in other bill shapes: the 'akialoa (probably extinct) foraged among leaves and branches; the alauahio feeds on insect larvae and nectar of ohi'a and lobelia flowers; and the Maui parrotbill crushes twigs to find prey.

Endemic species evolved in the Hawaiian Islands from ancestral colonizers and are unique to a specific area. Haleakalā 'ahinahina is a silversword endemic to the upper slopes of Haleakalā. This 'ahinahina grows as a compact rosette of narrow silvery leaves for up to 50 years before finally flowering. After flowering once in its lifetime, the plant dies. The endemic insects that pollinate the Haleakalā 'ahinahina are essential to the long-term survival of these fragile plants and are dependent on them for nourishment.

Foreign species of plants and animals introduced purposely or accidentally by humans are known as aliens. Alien species have reduced populations of native Hawaiian species and in some cases threaten their survival. Aggressive alien plants, like kahili ginger, can spread into remote forests, displacing native vegetation. Goats eliminate vegetation, resulting in severe erosion. Mongooses, originally brought to the Hawaiian Islands to control rats in sugar cane fields, prey on the eggs and young of ground-nesting birds.

The State of Hawaii includes only two-tenths of a percent of the total U.S. land area, yet one-third of the plants and birds listed or considered for listing on the Federal Endangered Species List are Hawaiian. The impact of human activities on native species and ecosystems cannot be completely undone, but active management is limiting and even reversing some of the damage. Today's natural area managers build fences, control alien species, restore native vegetation, and work to increase our knowledge of Hawaiian ecosystems.

The long, curved bill of the 'i'iwi, a rain forest honeycreeper, is ideally adapted to sipping nectar from the tubular flowers of Hawaiian lobelias. As lobelia species have declined due to deforestation and the introduction of grazing and browsing animals, the 'i'iwi is often found feeding on the smaller flowers of the 'ōhi'a. Other species have not been so successful in adapting to the rapid changes brought on by humans. Eighty-five species of Hawaiian birds have become extinct and 32 are on the Federal Endangered Species List, with seven of these possibly already extinct or on the brink. The extinction crisis is real. We can't take back what has been done, but what we do now is important.

Diversity on Haleakalā

Found at the highest elevations, the alpine/aeolian zone appears barren. Rainfall sinks rapidly into the porous, rocky ground, whose bare surface becomes summer every day, winter every night. Few plant species can establish seedlings in this harsh environment, and plant cover is sparse; only a few hardy shrubs, grasses, and the 'ahinahina (silversword) survive. Unique communities of insects and spiders thrive by feeding on wind-imported insects, other organic matter, and moisture from lower elevations.

The subalpine shrubland covers extensive areas below the alpine/aeolian zone and above the forest line. Over a dozen species of shrubs and grasses inhabit this zone, many found nowhere else on Earth. Shrubs are sparse in the shallow soils at higher elevations, but form dense thickets where soils are deeper. The shrubs provide food for many bird species, including the nēnē (Hawaiian goose).

Rain forest occupies the windward slopes of Haleakalā. Annual rainfall ranges from 120 inches to 400 inches or more. The forest canopy is dominated by 'ōhi'a trees in the upper elevations, grading into a mixed 'ōhi'a and koa canopy at lower levels. Diverse vegetation—smaller trees, ferns, shrubs, and herbs—grows in the understory. One of the most intact rain forest ecosystems in Hawaii, the Kīpahulu Valley is home to numerous rare birds, insects, and spiders.

The dry forest zone is found on the leeward slopes of Haleakalā, in areas with 20 to 60 inches of annual rainfall. Dry forests may once have been more extensive than rain forests, but browsing animals, grass invasions, and fire have drastically reduced them. Small patches of dry forest are preserved in Kaupo Gap.

Cutting across several life zones, stream ecosystems hosting fish, shrimp, and limpets meet the lowland/coastal zone. These low elevation ecosystems have been more heavily modified by humans than any other life zone. Native shrubs and herbaceous plants remain only in pockets along the coast.

The trail leading from Kīpahulu Visitor Center to 400-foot Waimoku Falls winds for 1.83 miles through a forest of non-native plants like bamboo, mango, and guava. Farther up the valley, above 1,000 feet, the Kīpahulu Valley Biological Reserve protects one of the last intact native rain forest ecosystems left in the Hawaiian Islands. To help preserve this fragile, pristine environment, the reserve is closed to the public. Researchers and managers study this little-known system and attempt to control the encroachment of non-native species.

The Shaping of Maui

East and West Maui began life millions of years ago ais two of a group of five shield volcanoes. These volcanoes rose from the ocean floor with countless eruptions of lava, eventually emerging from the sea to form volcanic islands. A million years ago the growing islands had coalesced into a huge single island with multiple volcanic peaks.

Eruptions continued until about 400,000 years ago, building a mountain (Haleakalā) on East Maui that rose higher than today's 10,023-foot summit. At the same time the forces of erosion and subsidence were reducing the height of the volcanic peaks and flooding the lowlands between them. By 150,000 years ago the peaks had separated, forming the islands of Maui, Kaho'olawe, Lāna'i, and Moloka'i.

As water and wind cut large valleys into the sides of East Maui, upstream erosion created the dramatic features composing today's park. The amphitheater-like heads of Ke'anae, Kaupō, and Kīpahulu valleys slowly cut their way toward the summit. The first two eventually merged, forming a huge basin at the top. Later, new lava flows partially filled the basin. Numerous volcanic vents, called cinder cones, mark the younger eruption sites.

Countless times over hundreds of thousands of years, hot lava met the ocean amidst clouds of steam. Each time the island grew a little larger. Today sharks, octopi, green sea turtles, humpback whales (winter only), and fish inhabit the coastal waters of Kīpahulu. Many of the native stream dwellers in the Hawaiian Islands were originally ocean species that over time adapted to live in fresh water. The 'o'opu (gobies), bottom fish with frog-like faces, spend their adult lives in streams. After adults spawn, the eggs are washed out to sea. As hatchlings the young 'o'opu migrate back up to the freshwater pools where they began their lives. Suction cups (actually fused fins) on their bellies aid the 'o'opu in their upstream journey.

Hiking Haleakalā

Summit Area Trails

A number of trails in the summit area allow for trips ranging

½-mile self-guiding nature trail at Hosmer Grove, with a 120-foot

elevation change each way, and a ½-mile nature trail to Leleiwi

Overlook, with a 40-foot elevation change each way. There are over 30

miles of hiking trails within the Wilderness Area. Two trails, Halemau'u

and Sliding Sands, enter the wilderness from the summit area, with a

third trail exiting to the coast via Kaupõ Gap.

Kīpahulu Area Trails

Pīpīwai Trail (3.7 miles round trip, 800-foot elevation change each way)

passes the 184-foot waterfall at Makahiku, winding through alien bamboo

and guava forests to the base of the 400-foot Waimoku Falls.

Kūloa Point Loop Trail (½-mile round trip, 80-foot elevation change each way) leaves Kīpahulu Visitor Center and continues past a Hawaiian cultural demonstration area to Kūloa Point at the mouth of the stream. Hikers can swim in several pools and waterfalls along the lower stream. Swimmers should use caution. (See "Swimming" below.)

Kahakai Trail (½-mile round trip, 15-foot elevation change each way) extends from Kūloa Point, along the shore, to the Kīpahulu campground.

The coastal Kīpahulu area once supported a large population of Hawaiians. Current estimates place several hundred thousand people in the Hawaiian Islands at the time of Captain Cook's arrival in 1778.

These people were skilled at fishing, farming, collecting, and craftwork. Management of their resources was based on mālama 'āina (caring for the land), an ideal still alive among Hawaiians today. Successful farming, fishing, and gathering depended also on the concepts of lōkahi (working together) and laulima (many hands). Lo'i kalo (taro patches), fishing shrines, heiau (temples), canoe ramps, and retaining walls are lasting reminders of these dynamic cultural ideals.

Hawaiians adapted to some Western influences on dress and on architectural elements such as the Western door. At the same time they maintained their basic cultural identity and continued to live in extended families. This social unit remained intact for pursuing agricultural and cooperative fishing ventures and gathering materials. The hālau (long house) was the community gathering place. Buildings were usually thatched with pili grass, although other materials, including lauhala (pandanus leaves), were used. Being greeted with aloha and invited into a home to eat (Aloha, e 'ai kākou) is still a primary requisite of good manners in the Hawaiian Islands.

Hawaiians showed great skill in creating ingenious and beautiful practical items from stone, bone, wood and shell. A broad range of tools and utensils, like poi pounders, fish hooks, octopus lures, and adzes, were fashioned using only stone implements. The poi pounder was one of the most frequently used. Poi was prepared fresh daily by pounding cooked corms (underground stems) of the kalo (taro) plant and thinning them with water to the desired consistency.

Visiting the Park

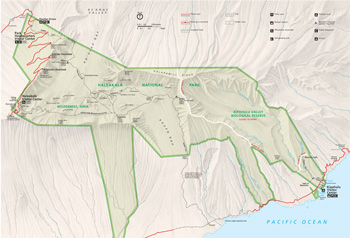

(click for larger map) |

Visitors to the park can explore the summit area or the Kīpahulu area on the coast. Park headquarters and the 10,023-foot summit can be reached from Kahului via Hawaii 37 to 377 to 378. Driving time to the summit from the resort areas of Kīhei and Kā'anapali is about two hours. Kīpahulu is reached via Hawaii 36 to 360 to 31. Driving time from resort areas to Kīpahulu is three to four hours.

Weather Weather and viewing conditions at the summit are unpredictable and can change rapidly. Be prepared for cold (30-50°F), wet, windy weather (10—40 mph) and intense sun. Sunrise is often clear, but the summit is a popular spot, so expect crowds. Kīpahulu is subtropical with light rain showers occurring anytime of the year.

Driving Vehicles must remain on roads or in parking areas. Road hazards in and en route to the park include steep turns, rocks, fog, rain, slippery pavement, cattle, bicyclists, large buses, and heavy traffic. When driving down from the summit of Haleakalā, use lower gears to prevent brake failure. Slower vehicles must use pullouts. If you have mechanical problems, move your vehicle out of traffic lanes to wait for help.

Regulations and Safety Report accidents, violations, unusual incidents, or sightings of alien species to a ranger. Bicycles are restricted to paved roads and parking areas. Prohibited: hunting, firearms, in-line skates, and skateboards.

High altitude may complicate health conditions and cause breathing difficulties. Pregnant women, young children, and those with respiratory or heart conditions should consult their doctor regarding travel to high elevations. Turn back and seek medical aid if you have problems. The summit is about 30°F colder than beaches. The weather conditions change rapidly. Hypothermia is a possibility any time of year.

Activities and Facilities Begin your visit by stopping at one of the visitor centers: Park Headquarters Visitor Center (7,000 feet), Haleakalā Visitor Center (9,740 feet) in the summit area, or the Kīpahulu Visitor Center. An entrance fee is charged to enter the summit area. No food or gas is available in the park. No water is available at Kīpahulu. Public phones are at park headquarters and the Kīpahulu parking lot.

Ranger Programs Talks and hikes are offered regularly. Groups may arrange special programs subject to staffing; call at least one month in advance. Contact the park for details.

Hiking Trails are rugged and strenuous. Hiking off designated trails and cutting switchbacks are prohibited; they cause erosion and unsightly scars that mar the scenery for years to come. Off-trail hikers can unknowingly crush the roots of native plants, like silversword, and trample unique insert species living among the rock and cinder.

Wilderness Area water supplies are not potable; water should be treated before drinking. Use portable toilets where provided. If toilets are not available, bury your waste and carry out paper; waste attracts alien ants that kill native species. Open fires are not permitted in the Wilderness Area. Sunscreen and plenty of water are essential.

Pets Pets must be physically restrained at all times and are not allowed on trails. Nēnē and other ground-nesting birds are vulnerable to harassment and predation.

Camping Wilderness Area camping is allowed only at Hōlua and Palikū. Required permits are free—first-come, first-served—at park headquarters on the day of the trip. Use cooking stoves only. No fire!

Drive-in campgrounds are available at Hosmer Grove and Kīpahulu—first-come, first-served. No permit is required, and no fee is charged. Grills, picnic tables, and restrooms are provided at both campgrounds. Hosmer Grove has water. NO water is available at Kīpahulu. Fires are allowed only in the grills.

At all campgrounds, stays are limited to three nights per month and group size is limited to 12 people.

Wilderness Area Cabins Three primitive cabins, accessible only by hiking or horseback, are in the Wilderness Area. Cabins are by reservation only. Call three months before your requested day for reservations or to fill vacancies. Cabins are rented to one group of up to 12 people per night. Stays are limited to three nights per month.

Swimming Kīpahulu streams are very dangerous at high water—the water can rise four feet in 10 minutes. People have died by ignoring warnings. Swimming is also not recommended when streams are stagnant and not flowing. Ocean swimming is not recommended due to high surf and currents.

Plants and Animals Remove seeds from boots, rain gear, and tents before entering the park. One of the greatest threats to native species is the introduction of alien plants, seeds, and animals. Although some species like the nēnē (Hawaiian goose) act tame, they are wild. Do not feed nēnē or other wildlife. Feeding causes the animals to beg and endangers them as they approach moving vehicles.

Cultural Resources All cultural resources are protected by law. It is illegal to alter, remove, damage, or destroy these resources. If you find an artifact, leave it in place and report the discovery to park staff. Do not create imitation artifacts by gathering or stacking rocks in ahu (piles).

Agricultural practices in the Islands were carefully managed according to the rhythms of nature. Mahi'ai (farmers) specialized in growing crops such as kalo or 'uala (sweet potato). The Hawaiian calendar recommended planting based on the changes of a year-round growing season. As with much of Hawaiian life, respect for the spiritual realm was shown during every phase of planting and harvesting. Fundamental patterns of Hawaiian culture were based on the planting and growth cycle of this plant. The concept of 'ohana (the family) is derived from 'oha, the sprout used to propagate kalo. The 'ohana worked together to build extensive irrigated terraces for the growing of over 300 varieties of kalo.

Approximately 1,500 years ago, Polynesian colonists sailed large double-hulled canoes on migrational voyages from the South Pacific. They navigated over 2,500 miles of open ocean using nature's signs—stars, birds, winds, tides, and currents. To sustain themselves the Polynesians brought to the Hawaiian Islands food and medicinal plants, introducing kalo, 'uala (sweet potato), uhi (yams), 'ulu (breadfruit), and kō (sugar cane), as well as dogs, pigs, and chickens. Koa trees, found only on the Hawaiian Islands, provided logs for hulls of double- and single-hulled canoes. Single outrigger canoes were mainly used by lawai'a (fishermen) to catch deepwater fish such as aku (bonito).

Source: NPS Brochure (2012)

Documents

2021 US National Seismic Hazard Model for the State of Hawaii (Mark D. Petersen, Allison M. Shumway, Peter M. Powers, Morgan P. Moschetti, Andrea L. Llenos, Andrew J. Michael, Charles S. Mueller, Arthur D. Frankel, Sanaz Rezaeian, Kenneth S. Rukstales, Daniel E. McNamara, Paul G. Okubo, Yuehua Zeng, Kishor S. Jaiswal, Sean K. Ahdi, Jason M. Altekruse and Brian R. Shiro, extract from Earthquake Spectra, September 22, 2021)

A General Index to Lassen Nature Notes, 1932-1936 and Hawaii Nature Notes, 1931-1933 (Hazel Hunt Voth, 1938)

A Morphometric analysis and taxonomic appraisal of the Hawaiian Silversword Argyroxiphium sandwicense Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 46 (Alain K. Meyrat, October 1982)

A test of four herbicides for use against strawberry guava (Psidium Cattleianum) in Kipahulu Valley, Haleakala National Park Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 90 (Linda W. Pratt, Gregory L. Santos and Charles P. Stone, June 1994)

An Administrative History of Hawaii Volcanoes National Park and Haleakala National Park (Frances Jackson, 1972)

An archaeological survey of Haleakala (1921)

An Ecological Survey of Pua'alu'u Stream Cooperative National Park Resources Study Unit Technical Report 27 (July 1979)

Part I. Biological Survey of Pua'alu'u Stream, Maui Cooperative National Park Resources Study Unit Technical Report 27 (R.A. Kinzie, III and J.I. Ford, July 1989)

Part II. Catalogue of the Vascular Plants at Pua'alu'u, Maui Cooperative National Park Resources Study Unit Technical Report 27 (P.K. Higashino and L.K. Croft, July 1979)

Part III. Report of Preliminary Entomological Survey of Pau'alu'u Stream, Maui Cooperative National Park Resources Study Unit Technical Report 27 (D.E. Hardy, July 1979)

Bryophytes and vascular plants of Kipahulu Valley, Haleakala National Park Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 65 (Paul K. Higashino, Linda W. Cuddihy, Stephen J. Anderson and Charles P. Stone, August 1988)

Civilian Conservation Corps In Hawai'i: Oral Histories of the Haleakala Camp, Maui (Kathryn Ladoulis Urban and Stanley Solamillo, July 20, 2011)

Climatology of Haleakalā Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 193 (Ryan J. Longman, Thomas W. Giambelluca, Michal A. Nullet and Lloyd L. Loope, 2015)

Critical assessment of habitat for release of Maui Parrotbill Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 146 (Valerie Stein, August 2007)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Civilian Conservation Corps Haleakala Crater Trails District (2009)

Ecology of introduced gamebirds in high-elevation shrubland Haleakala National Park Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 96 (Russell F. Cole, Lloyd L. Loope, Arthur C. Medieros, Jane A. Raikes, Cynthia S. Wood, and Laurel J. Anderson, September 1995)

Efforts at Control of the Argentine Ant in Haleakala National Park, Maui, Hawaii Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 109 (Paul D. Krushelnycky and Neil J. Reimer, December 1996)

Eruptions of Hawaiian Volcanoes: Past, Present, and Future USGS General Information Product 117 (Robert I. Tilling, Christina Heliker, and Donald A. Swanson, 1987)

Eruptions of Hawaiian Volcanoes: Past, Present, and Future USGS General Information Product 117 (Robert I. Tilling, Christina Heliker, and Donald A. Swanson, 2010)

Exploratory drilling and aquifer testing at the Kipahulu District, Haleakala National Park, Maui, Hawaii USGS Water-Resources Investigations Report 83-4066 (1983)

Exploring spatial patterns of overflights at Haleakalā National Park NPS Science Report NPS/SR-2025/224 (Bijan Gurung, J.M. Shawn Hutchinson, Brian A. Peterson, J. Adam Beeco, Sharolyn J. Anderson and Damon Joyce, February 2025)

Flowering plant and gymnosperms of Haleakala National Park Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 120 (A.C. Medeiros, L. L. Loope and C. G. Chimera, June 1998)

Forest bird and non-native mammal inventories at Ka'apahu, Haleakalā National Park, Maui, Hawai'i Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 145 (Cathleen Natividad Bailey, ed., July 2007)

Forest Bird Population Trends Within Haleakalā National Park Hawai'i Cooperative Studies Unit Technical Report HCSU-097 (Kevin W. Brinck, September 2020)

Foundation Document, Haleakala National Park, Hawai'i (September 2015)

Foundation Document Overview, Haleakala National Park, Hawai'i (January 2015)

General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement Haleakala National Park, Hawaii (1995)

Geologic map of the Crater section of Haleakala National Park, Maui, Hawaii USGS IMAP 1088

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Haleakalā National Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2011/453 (T.L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, September 2011)

Haleakala National Crater District Resources Basic Inventory: 1976-1977 Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 24 (L. Stemmermann, Clifford W. Smith and W. J. Hoe, April 1979)

Haleakala National Crater District Resources Basic Inventory: Birds Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 26 (Sheila Conant and Maile Stemmermann, July 1979)

Haleakala National Park Crater District resources basic inventory: conifers and flowering plants Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 38 (L. Stemmermann, P. K. Higashino and C. W. Smith, July 1981)

Haleakala National Park Crater District resources basic inventory: ferns and fern allies Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 39 (Tissa Herat, Paul K. Higashino and Clifford W. Smith, July 1981)

Haleakala National Park Crater District Resources Basic Inventory: Insects Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 31 (John Beardsley, July 1980)

Haleakala National Crater District Resources Basic Inventory: Mosses Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 25a (William J. Hoe, June 1979)

Haleakala National Park resources basic inventory, 1975: narrative report Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 9 (Clifford W. Smith, ed., with Andrew J. Berger, John Beardsley, Robert Burkhart, Paul K. Higashino, William J. Hoe, and H. Eddie Smith, November 1975)

Hawaii National Park (United States Railroad Administration, 1919)

Hawaii Nature Notes (1931-1959)

Hawai'i, the Military, and the National Park: World War II and Its Impacts on Culture and Environment (William Chapman, et al., 2014)

Hawaiian Subalpine Plant Communities: Implications of Climate Change (Alison Ainsworth and Donald R. Drake, extract from Pacific Science, Vol. 77 No. 2-3, 2023, ©University of Hawai'i Press)

Hawaiian Treeline Ecotones: Implications for Plant Community Conservation under Climate Change (Alison Ainsworth and Donald R. Drake, extract from Plants, Vol. 13, 2024)

History on the Road: The Hosmer Grove at Haleakalā National Park (Steven Anderson, extract from Forest History Today, Spring 2012)

Inventory of arthropods of the west slope shrubland and alpine ecosystems of Haleakala National Park Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 148 (Paul D. Krushelnycky, Lloyd L. Loope and Rosemary G. Gillespie, September 2007)

Junior Ranger Activity Booklet, Haleakalā National Park (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Kilauea — an Explosive Volcano in Hawai'i USGS Fact Sheet 2011-3064 (Dan Swanson, Dick Fiske, Time Rose, Bruce Houghton and Larry Mastin, July 2011)

Kipahulu Valley research plan Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 22 (Clifford W. Smith, October 1978)

Limnological survey of lower Palikea and Pipiwai Stream, Kipahulu Maui Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 17 (Robert A. Kinzie, III and John I. Ford, May 1977)

Living on Active Volcanoes — The Island of Hawai'i USGS Fact Sheet 074-97 (Christina Heliker, Peter H. Stauffer and James W. Hendley II, June 2000)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Haleakalā National Park (January 2003)

Mauna Loa — History, Hazards, and Risk of Living With the World's Largest Volcano USGS Fact Sheet 2012-3104 (Frank A. Trusdell, August 2012)

Monitoring of the freshwater amphidromous populations of the 'Ohe'o Gulch Stream system and Pua'alu'u Stream, Haleakala National Park Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 93 (Marc H. Hodges, December 1994)

National Parks in Hawaii University of Hawaii Cooperative Extension Circular 443 (Wade W. McCall, February 1972

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Crater Historic District, Haleakala National Park (Thomas Vaughn and Russell A. Apple, rev. E.J. Ladd, c1974)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Haleakala National Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HALE/NRR-2019/1977 (Paul D. Krushelnycky, Charles G. Chimera and Eric A. VanderWerf, August 2019)

Night Skies Data Report: Photometric Assessment of Night Sky Qua.ity at Halekalā National Park NPS Science Report NPS/SR-2024/170 (Erik Meyer, September 2024)

Ohia Decline: The Role of Phytophthora Cinnamomi Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 12 (Shin-Chuan Hwang, February 1977)

'Ohi'a Dieback in Hawaii: 1984 Synthesis and Evaluation (Dieter Mueller-Dombois, extract from Pacific Science, Volume 39, Number 2, 1985)

Ohia Rain Forest Study: Ecological Investigations of the Ohia Dieback Problem in Hawaii Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 20 (Dieter Mueller-Dombois, James D. Jacobi, Ranjit G. Cooray and N. Balakrishnan, December 1977)

Park Newspaper (Park Guide): Date Unknown

Plants of Haleakala National Park

Crater Aeolian Desert (Date Unknown)

Invasive Plants of Haleakalā National Park (Date Unknown)

Kaupo Mesic Forest (Date Unknown)

Kipahulu Coastal Strand (Date Unknown)

Subalpine Shrubland (Date Unknown)

Predicting Impacts of Sea Level Rise for Cultural and Natural Resources in Five National Park Units on the Island of Hawai'i Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 188 (Lisa Marrack and Patrick O'Grady, June 2014)

Proposal to study feral pigs in Kipahulu Valley, Haleakala National Park Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 19 (Clifford W. Smith and Cheong H. Diong, September 1997)

Prospects for biological control of non-native plants in Hawaiian National Parks Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 45 (Donald E. Gardner and Clifton J. Davis, October 1982)

Report of the Kipahulu Bicentennial expedition Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 11 (Charles H. Lamoureux and Lani Stemmermann, September 1976)

Resources Basic Inventory 1975: Narrative Report, Haleakala National Park Cooperative National Park Resources Study Unit Technical Report 9 (1975)

Resources Basic Inventory 1976-77: Haleakala National Park Crater District Cooperative National Park Resources Study Unit Technical Report 24 (L. Stermmermann, C.W. Smith and W.J. Hoe, April 1979)

Resources Basic Inventory: Birds, Haleakala National Park Crater District Cooperative National Park Resources Study Unit Technical Report 26 (Sheila and Maile Stemmermann, July 1979)

Resources Basic Inventory: Haleakala National Park Crater District Cooperative National Park Resources Study Unit Technical Reports 38 & 39 (July 1981)

Resources Basic Inventory: Conifers and Flower Plants Cooperative National Park Resources Study Unit Technical Report 38 (L. Stemmermann, P.K. Higashino and C.W. Smith, July 1981)

Resources Basic Inventory: Ferns and Fern Allies Cooperative National Park Resources Study Unit Technical Report 39 (T. Herat, P.K. Higashino and C.W. Smith, July 1981)

Resources Basic Inventory: Insects, Haleakala National Park Crater District Cooperative National Park Resources Study Unit Technical Report 31 (John Beardsley, July 1980)

Resources Basic Inventory: Mosses, Haleakala National Park Cooperative National Park Resources Study Unit Technical Report 25 (William J. Hoe, June 1979)

Seabird Inventory at Haleakala National Park, Maui, Hawai'i Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 164 (Cathleen S. Natividad Bailey, February 2009)

Shoreline Bird Inventories in Three National Parks in Hawaii: Kalaupapa National Historical Park, Haleakala National Park and Hawaii Volcanoes National Park Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 149 (Kelly Kozar, Roberta Swift and Susan Marshall, September 2007)

Some aspects of feral goat distribution in Haleakala National Park Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 52 (John Kjargaard, August 1984)

Status of native flowering plant species on the south slope of Haleakala, East Maui, Hawaii Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 59 (A.C. Medeiros, Jr., L. L. Loope and R. A. Holt, July 1986)

Status of the Silversword in Haleakala National Park: Past and Present Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 58 (Lloyd L. Loope and Carmelle F. Crivellone, May 1986)

Studies in montane bogs of Haleakala National Park: aspects of the history and biology of the montane bogs Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 76 (Lloyd L. Loope, Arthur C. Medeiros and Betsy H. Gagne, August 1991)

Studies in montane bogs of Haleakala National Park: degradation of vegetation in two montane bogs: 1982-1988 Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 78 (Arthur C. Medeiros, Lloyd L. Loope and Betsy H. Gagne, August 1991)

Studies in montane bogs of Haleakala National Park: recovery of vegetation of a montane bog following protection from feral pig rooting Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 77 (Lloyd L. Loope, Arthur C. Medeiros and Betsy H. Gagne, August 1991)

Superintendent Annual Reports

1922-1928 •

1927-1945 •

1928-1931 •

July 1931-June 1932 •

July 1932-June 1933 •

July-Dec 1933 & Jan-June 1935 •

1934 •

July 1935-Dec 1936 •

1937 •

1938 •

1939 •

1940 •

1941 •

1942-1943 •

1944-1945 •

1946-1947 •

1948 •

1949

Supplement to technical report 25, Haleakala National Park Crater District resources basic inventory: mosses Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 25b (William J. Hoe, June 1979)

The Haleakala Argentine ant project: a synthesis of past research and prospects for the future Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 173 (Paul Krushelnycky, William Haines, Lloyd Loope and Ellen Van Gelder, June 2011)

The Ohia dieback problem in Hawaii Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 3 (Dieter Mueller-Dombois, July 1974)

The status and distribution of ants in the crater district of Haleakala National Park Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 40 (Johan H. Fellers and Gary M. Fellers, September 1981)

The vegetation and environment in the Crater District of Haleakala National Park Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 35 (Louis D. Whiteaker, October 1980)

The Volcano Letter (complete set, ~1gb) or download by decade: 1920s • 1930s • 1940s • 1950s (The Volcano Letter is in the public domain, 1925-1955; the Preface, Acknowledgements, Introduction and Index are ©Smithsonian Institution, Robert S. Fiske, Tom Simkin and Elizabeth A. Nielsen, eds., 1987)

Upper Kipahulu Valley weed survey Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 33 (Alvin Y. Yoshinaga, September 1980)

Vascular plant inventory of Ka'apahu, Haleakala National Park Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 151 (Patti Welton and Bill Haus, February 2008)

Vegetation changes in a subalpine grasslands in a subalpine grassland in Hawaii following disturbance by feral pigs Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 41 (James D. Jacobi, September 1981)

Vegetation map and resource management recommendations for Kipahulu Valley (below 700 meters), Haleakala National Park Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 53 (Clifford W. Smith, Julia E. Williams and Karen E. Asherman, March 1985)

Viewing Hawai'i's Lava Safely — Common Sense is Not Enough USGS Fact Sheet 152-00 (Jenda Johnson, Steven R. Brantley, Donald A. Swanson, Peter H. Stauffer and James W. Hendley II, December 2000)

Yellowjacket (Vespula pensylvanica): biology and abatement in the National Parks of Hawaii Pacific Islands Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 86 (Parker Gambino and Lloyd L. Loope, February 1992)

Haleakala National Park, Hawaii

Haleakalā: A Rare and Sacred Landscape (June 19, 2019)

hale/index.htm

Last Updated: 14-Feb-2025