|

Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site North Dakota |

|

NPS photo | |

For centuries the Upper Missouri River Valley was a lifeline winding through a harsh land, drawing Northern Plains Indians to its wooded banks and rich soil. Earthlodge people, like the nomadic tribes, hunted bison and other game but were essentially farmers living in villages along the Missouri and its tributaries. At the time of contact with Europeans, these communities were the culmination of more than 500 years of settlement in the area. Traditional oral histories link the ancestors of the Mandan and Hidatsa tribes living on the Knife River with tribal groups east of the Missouri River. Migrating for several hundred years along waterways, they eventually settled along the Upper Missouri. One Mandan story tells of the group's creation along the river. Coming into conflict with other tribes, the Mandan moved north to the Heart River and adopted architecture using round earthlodges.

The Hidatsa were originally divided into three distinct sub-tribes. The Awatixa were created on the Missouri River, according to their traditions. Awaxawi and Hidatsa-Proper stories place them along streams to the east. The Hidatsa moved farther north to the mouth of the Knife, settling Awatixa Xi'e Village (Lower Hidatsa Site) around 1525 and Hidatsa Village (Big Hidatsa Site) about 1600. The Hidatsa borrowed from the Mandan, learning corn horticulture and adopting some of their pottery patterns. Inter-marriage and trade helped cement relations, and eventually the two cultures became almost indistinguishable. With the Arikara to the south, they formed an economic force that dominated the region.

These three tribes shared a culture superbly adapted to the conditions of the Upper Missouri River Valley. Their summer villages, located on natural terraces above the river, included up to 120 lodges. These circular structures sheltered families of 10 to 30 people from the region's extreme temperatures. The villages were strategically located for defense, often on a narrow bluff with water on two sides and a palisade on the third. In winter the inhabitants moved into smaller lodges along the river, where trees provided firewood and protection from the wind.

The 1837 smallpox epidemic greatly reduced the populations of the Indian nations. By 1845 the Mandan and Hidatsa moved about 40 miles up the Missouri River to form a new village, Like-A-Fishhook. For mutual defense the Arikara joined them in 1862. In 1885 the U.S. Government forced the tribes to abandon Like-A-Fishhook and make a final move to the Fort Berthold Reservation as part of the Fort Laramie Treaty. Today their nation is known as the Three Affiliated Tribes.

Western Contact

When trader Pierre de la Verendrye walked into a Mandan village in 1738—the first recorded European to see Indians of the upper Missouri—he found an American Indian society at the height of prosperity. His arrival was the start of a relentless process that within 100 years transformed a culture. At first the three tribes remained relatively isolated, although there were increasing contacts with French, Spanish, English, and American traders. Their culture was still healthy when explorer David Thompson reached the area in 1797, but the pace of change quickened after Lewis and Clark visited in 1804. Explorers such as Prince Maximilian of Wied and artists such as Karl Bodmer and George Catlin drew sharp portraits of a society in transition. An influx of fur traders set up new trade patterns that undermined the tribes' traditional position as middlemen. The village people grew more dependent on European goods such as horses, weapons, cloth, and iron pots. Diseases brought by Europeans and overhunting of the bison further weakened the failing cultures.

Finally, the Federal Government moved the tribes to individually owned reservation plots and told them to grow wheat. Their societies and rituals were banned. Within one generation the three tribes were forced into radical changes that eroded their ancient relationship with the land and ended a way of life.

Village Life on the Upper Missouri

Lewis and Clark Encounter Indian Village Life

In 1804-05 Lewis and Clark's expedition, the Corps of Discovery, experienced upper Missouri village life firsthand. With orders from President Thomas Jefferson, Captains William Clark and Meriwether Lewis embarked on the adventure of their lives—to locate the Northwest Passage across the newly acquired Louisiana Purchase. After leaving St. Louis on May 14, 1804, and traveling 1,600 miles up the Missouri River, they arrived at what is now the Knife River Indian Villages. With cold weather approaching, the Corps built a fort and spent the winter among the Mandan and Hidatsa. Lewis noted in his journal, "This place we have named Fort Mandan in honour of our Neighbors."

Throughout the winter Mandan and Hidatsa people visited the fort to trade corn, beans, and squash and share information with the expedition party. Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian trader who had been living with the Hidatsa, came to the fort to ask about being hired as an interpreter. Along with Charbonneau came his Shoshone wife, Sakakawea (Sacagewea). Lewis and Clark knew that her translations of the tribal languages to the west would be invaluable. Charbonneau was hired, and the couple spent much of the winter at the fort. There Sakakawea gave birth to her first child, Jean Baptiste, who Clark nicknamed "Pomp."

On April 7, 1805, the Corps left the fort, and after many hardships reached the Pacific Ocean. To their disappointment they had discovered no waterway from St. Louis to the Pacific. The captains had hoped to reach the west coast in time to catch a boat back to St. Louis but were too late, so the expedition was forced to spend the 1805-06 winter in a structure they named Fort Clatsop. Anxious to return home, the Corps set out prematurely for St. Louis on March 23, 1806. On reaching the Rocky Mountains on June 15, they realized they would have to wait, as snow in the mountains was too deep. A couple of weeks later they made it over the mountains. By August 17, 1806, the expedition had returned to the confluence of the Knife and Missouri rivers. They bade farewell to Charbonneau, Sakakawea, and Pomp, who left the expedition to live with Hidatsa relatives. As Lewis and Clark headed downstream they noted in their journals that most of Fort Mandan had been washed away by the river and another part had burned. On September 23 Lewis and Clark reached St. Louis amidst cheers for their safe return.

Village Economy

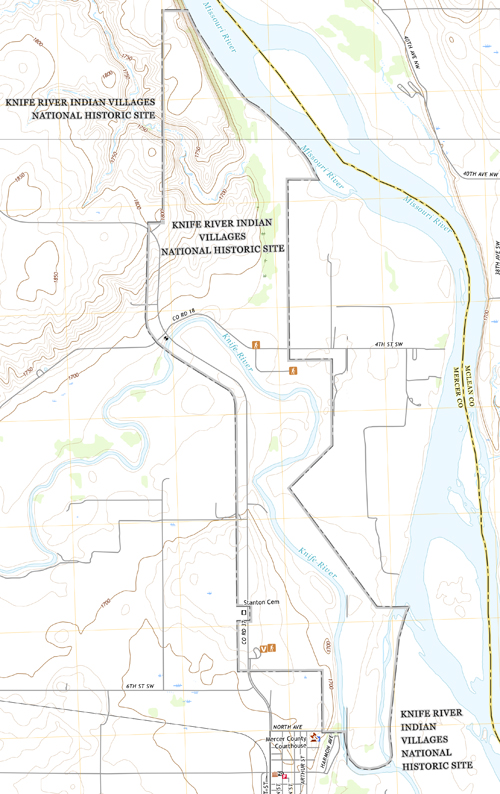

(click for larger maps) |

Agriculture underlay the economy of the Hidatsa and Mandan, who harvested much of their food from the rich floodplain gardens. Gardens, like earthlodges, were passed down through the female line. Women tended gardens, raising corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers. The size of the family and the number of women who could work in the garden determined the size of the plot. Summer's first green corn was celebrated in the Green Corn ceremony. Berries, roots, and fish supplemented their diet. Upland hunting provided bison, deer, and small game animals for meat, hides, bones, and sinew.

These proficient farmers traded their produce and Knife River flint to nomadic tribes for buffalo hides, deerskins, dried meat, catlinite (red pipestone), and items in short supply. Knife River flint is one of the best materials for making stone tools. It was quarried locally and traded throughout North America. Because of their location at the junction of major trade routes, the Hidatsa and Mandan became middlemen in the trade. Items brought into the villages for trade with other tribes included obsidian from Wyoming, copper from the Great Lakes region, dentalium shell from the West coast, and during the 1800s, guns, horses, and metal items from the Europeans.

Battle and Hunt

In this warrior culture, raiding and hunting were the chief occupations of the men. When conflict was imminent, a war chief assumed leadership of the village Tangible results—horses and loot—often came from the raids. Hunting parties were also scheduled, with a respected hunter choosing participants and planning the event. Prowess in battle and hunt led to status in the village, both individually and for the societies and clans. Ambitious young men would risk leading a party—highly rewarding if successful, ruinous to a reputation if not. The primary weapon was the bow and arrow, along with clubs, tomahawks, lances, shields, and knives. Ambition did not spur every action. Warriors often had to defend the village against raids by other tribes. When the men prevailed in battle or hunt, women celebrated with dance and song throughout the village.

Spirit and Ritual

Spirits guided the events of the material world, and, from an early age, tribal members (usually male) sought their help. Fasting in a sacred place, a boy hoped to be visited by a spirit, often in animal form, who would give him power and guide him through life. The nature of the vision that he reported to his elders determined his role within the tribe. If directed by his vision, he would as a young man make a greater sacrifice to the spirits, spilling his blood in the Okipa ceremony. The Okipa was the most important of a number of ceremonies performed by Mandan clans and age-grade societies to ensure good crops, successful hunts, and victory in battle. Ceremonies could be conducted only by those with "medicine," which was obtained by purchasing from a fellow clan or society member one of the bundles of sacred objects associated with tribal mythology. With bundle ownership came responsibility for knowledge of the songs, stories, prayers, and rituals necessary for spiritual communication. Certain bundle owners were looked upon as respected leaders of the tribe.

Reading the Past

The story of Knife River is still being written. Long-held theories have been revised by recent archeological research. From 1976 to 1983 Dr. Stanley Ahler of the University of North Dakota directed excavations here, recovering more than 800,000 artifacts. After piecing the story together from these artifacts. Dr. Ahler believes that the Hidatsa arrived here around 1300, earlier than once thought. Evidence from village sites provides an unbroken record of more than 500 years of habitation. This period, however, represents only a fraction of the time that humans lived here. Evidence from 50 archeological sites shows that the Knife River area has been occupied for more than 11,000 years. The earliest known people were the Paleo-Indians (11,000-6000 B.C.E. [Before Common Era]). The earliest artifacts from Knife River date from this period. These nomadic tribes hunted now-extinct large game. Archaic people came next (6000 B.C.E.-1 C.E.). These people lived by hunting and gathering. Signs of semi-sedentary living and rudimentary agriculture occur in the Woodland period (1000 B.C.E.-1000). Permanent earthlodge villages and a horticultural economy characterized the Plains Village Period (1000-1885); the Knife River sites represent one of the final phases.

Help us preserve this unique record of cultural development by leaving artifacts and site remains undisturbed. All natural and cultural resources in the park are protected by federal law.

About Your Visit

The area is 60 miles north of Bismarck, N.D. The park has a visitor center,

reconstructed earthlodge, (furnished with replica artifacts in summer), a film,

exhibits, remains of three village sites, and trails.

Source: NPS Brochure (2010)

|

Establishment Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site — October 26, 1974 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Acoustic Monitoring Report: Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/NSNS/NRR—2016/1303 (Jacob R. Job, September 2016)

Aquatic Invertebrate Monitoring at Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NGPN/NRTR—2013/778 (Lusha Tronstad, July 2013)

Archeological Resources Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site Final (March 2018)

Baseline Water Quality Data Inventory and Analysis: Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site NPS Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-97/127 (July 1997)

Breakdown of Relations: American Expansionism, the Great Plains, and the Arikara People, 1823-1957 (©Stephen Robert Aoun, Masters's Thesis Virginia Commonwealth University, April 2019)

Contact With Northern Plains Indian Villages and Communities: An Administrative History of Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, North Dakota (Anthony Godfrey, 2009)

Cultural Affiliation Statement and Ethnographic Resource Assessment Study for Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, Fort Union Trading Post National Historic Site, and Theodore Roosevelt National Park, North Dakota Final Report (Maria Nieves Zedeño, Kacy Hollenback, Christopher Basaldú, Vania Fletcher and Samrat Miller, December 8, 2006)

Elbee Site (32ME408) and Karishta Site (32ME466), 2010 Archeological Test Excavations, Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, Mercer County, North Dakota (Dennis L. Toom and Michael A. Jackson, March 2012)

Elbee Village Site (32ME408), 2003 Archeological Test Excavations, Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, Mercer County, North Dakota (Dennis L. Toom, Michael A. Jackson, Carrie F. Jackson, Zachary W. Wilson and Robert K. Nickel, October 2004)

Environmental Assessment/Revised General Management Plan for Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site (March 1986)

Foundation Document, Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, North Dakota (June 2013)

Foundation Document Overview, Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, North Dakota (July 2013)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2015/1016 (J.P. Graham, September 2015)

Geophysical Investigations of Three Sites within the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, Mercer County, North Dakota Midwest Archeological Center Archeology Report Series No. 10 (Steven L. De Vore, 2015)

Introduction To Middle Missouri Archeology Anthropologic Papers Series No. 1 (Donald J. Lehmer, 1971)

Junior Ranger Booklet (Ages 6-12), Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site (2012; for reference purposes only)

Like-A-Fishhook Village And Fort Berthold Garrison Reservoir North Dakota Anthropologic Papers Series No. 2 (Hubert G. Smith, 1972)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Big Hidatsa (or Olds) Village Site (32ME12) (April 29, 1964)

Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site Archeological District (Thomas D. Thiessen, c1987)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/KRI/NRR-2014/775 (Andrew J. Nadeau, Shannon Amberg, Kathleen Kilkus, Kevin Stark, Michael R. Komp, Eric Iverson, Sarah Gardner and Barry Drazkowski, February 2014)

Park Newspaper: 1990 • 2009 • 2011 • 2012 • 2014 • 2015 • 2016 • 2017

Phase I Archeological Research Program for the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site: Part I: Objectives, Methods, and Summaries of Baseline Studies Midwest Archeological Center Occasional Studies in Anthropology No. 27 (Thomas D. Thiessen, ed., 1993)

Phase I Archeological Research Program for the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site: Part II: Ethnohistorical Studies Midwest Archeological Center Occasional Studies in Anthropology No. 27 (Thomas D. Thiessen, ed., 1993)

Phase I Archeological Research Program for the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site: Part III: Analysis of the Physical Remains Midwest Archeological Center Occasional Studies in Anthropology No. 27 (Thomas D. Thiessen, ed., 1993)

Phase I Archeological Research Program for the Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site: Part IV: Interpretation of the Archeological Record Midwest Archeological Center Occasional Studies in Anthropology No. 27 (Thomas D. Thiessen, ed., 1993)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring Protocol for the Northern Great Plains I&M Network Version 1.01 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NGPN/NRR-2012/489 (Amy J. Symstad, Robert A. Gitzen, Cody L. Wienk, Michael R. Bynum, Daniel J. Swanson, Andy D. Thorstenson and Kara J. Paintner-Green, February 2012)

Plant Community Composition and Structure Monitoring Annual Reports: 2011 • 2012 • 2013 • 2014 • 2011-2016 • 2017 • 2018

Revised General Management Plan: Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, North Dakota (August 1986)

Statement for Management — Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site (March 1986)

The Arikara Indians and the Missouri River Trade: A Quest for Survival (Roger L. Nichols, extract from Great Plains Quarterly, Spring 1982)

The Geologic Story of the Great Plains USGS Bulletin 1493 (Donald E. Trimble, 1980, reprinted 1990)

The History and Culture of the Mandan, Hidatsa, Sahnish (Arikara) (Linda Baker, Dorreen Yellow Bird, Cheryl Kulas, Greta White Calfe, Yvonne Fox, Melvina Everett, Lena Malnourie and Rohda M. Star, 2020, ©North Dakota Department of Public Instruction)

Water Quality Monitoring for Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site: 2013 Data Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/KNRI/NRDS-2020/1257 (Isabel W. Ashton and Stephanie L. Rockwood, February 2020)

Water Quality Monitoring for Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site: 2016 Data Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/KNRI/NRDS-2020/1262 (Isabel Ashton and Stephanie Rockwood, February 2020)

Water Quality Monitoring for Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site: 2019 Data Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/KNRI/NRDS-2022/1382 (Anine T. Rosse and Myles J. Cramer, December 2022)

White-Nose Syndrome Surveillance Across Northern Great Plains National Park Units: 2018 Interim Report (Ian Abernethy, August 2018)

knri/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025