|

Mesa Verde National Park Colorado |

|

NPS photo | |

Ancestral Pueblo People and Their World

About AD 550, long before Europeans explored North America, some of the people living in the Four Corners region decided to move onto the Mesa Verde. For over 700 years these people and their descendants lived and flourished here, eventually building elaborate stone communities in the sheltered alcoves of canyon walls. In the late 1200s in the span of a generation or two, they left their homes and moved away.

Mesa Verde National Park preserves a spectacular reminder of this ancient culture. Archeologists have called these people Anasazi, from a Navajo word sometimes translated as "the ancient foreigners." We now call them Ancestral Pueblo people, reflecting their modern descendants.

Local ranchers first reported the cliff dwellings in the 1880s and since then archeologists have sought to understand the lives of the people who lived there. Despite decades of excavation, analysis, classification, and comparison, our knowledge is incomplete. The cliff dwellings speak eloquently of a people adept at building, artistic in their crafts, and skillful at making a living from a difficult land. The structures are evidence of a society that, over centuries, accumulated skills and traditions and passed them on from generation to generation. By the Classic Pueblo Period, from 1150 to 1300, Ancestral Pueblo people were heirs of a vigorous civilization, whose accomplishments in community living and the arts must be ranked among the finest expressions of human culture in North America.

Using nature to their advantage, about AD 1200 Ancestral Pueblo people began to build their villages beneath the overhanging cliffs. Their basic construction material was sandstone that they shaped into rectangular blocks about the size of a loaf of bread. The mortar between the blocks was a mix of dirt and water. Living rooms averaged about six feet by eight feet, space enough for two or three people. Isolated rooms in the rear and on the upper levels were generally used for storing crops. The construction testifies they were experienced builders.

Many daily activities took place in open courtyards in front of the rooms. Fires built in summer were mainly for cooking. In winter, when alcove rooms were damp and uncomfortable, fires probably burned throughout the village. Smoke-blackened walls and ceilings are reminders of the biting cold these people lived with for several months each year.

Ancestral Pueblo people spent much of their time getting food, even in the best years. They grew most of their food, but supplemented crops of beans, corn, and squash by gathering wild plants and hunting deer, rabbits, squirrels, and other animals. Their only domestic animals were dogs and turkeys. Fortunately, Ancestral Pueblo people tossed their trash close by. Scraps of food, broken pottery and tools, anything not wanted, went down the slope in front of their homes. Much of what we know about daily life here comes from these garbage heaps.

Spruce Tree House was one of the largest villages in Mesa Verde. It had 130 rooms and eight kivas. Some 60 to 90 people lived here at any time. Autumn was the villagers' busiest time of year. The harvest is underway. Some men are still gleaning the fields, while others are spreading the crops on a rooftop to dry. These are the stores that will see them through the long winter and even the next year or two if there is drought. Women are making pottery and grinding corn. Children scamper about, and old men sit in the sun telling stories.

Family Life at Mesa Verde

Ancestral Puebloan families wore hides, warm footwear, and feather-cloth robes for winter. The turkey was important in their economy—providing food, feathers used in weaving, and bones used for tools.

Archeology has yielded some facts about Mesa Verde's ancient people, but without a written record we cannot be sure about their social, political, or religious ideas. We must rely for insight on comparisons with modern Pueblo people of New Mexico and Arizona.

In the Classic Pueblo Period at Mesa Verde (from 1150 to 1300) several generations probably lived together as a household.

Each family occupied several rooms and built additional rooms as it grew. Several related families likely made up a clan, probably matrilineal, that traced descent through the woman's line. Based on current Hopi practices, each clan would have had its own kiva and its own agricultural plots.

Tools

Ancestral Pueblo people used all available materials, with no metals. From locally available trees, plants, animals, and stone they made tools for grinding, cutting, pounding, chopping, scraping, perforating, polishing, and weaving.

They used the digging stick for farming, stone axe for clearing land, bow and arrow for hunting, and sharp-edged stones for cutting. They ground corn with the metate and mano and made wooden or clay spindle whorls for spinning. From bone they fashioned awls for sewing and scrapers for working animal hides.

Other than the mano and metate, most stone tools were made from stream cobbles, not the soft cliff sandstone.

Trade

Mesa Verde's economy was more complex than you might think. Even in a small farming community, some people would have more skill than others at weaving, working leather, or making pottery, arrow-points, jewelry, baskets, sandals, or other specialized articles. A surplus would be shared or bartered with neighbors.

Exchanges also took place between communities. Seashells from the Pacific Coast and turquoise, pottery, and cotton from the south came to Mesa Verde, passed from village to village or carried by traders on foot over a far-reaching network of trails.

Basketry and Pottery

The finest baskets made at Mesa Verde were created before the people developed fired ceramic pottery. Using the spiral twilled technique, they wove handsomely decorated baskets of many sizes and shapes and used them for carrying water, storing grain, and even for cooking. They made baskets waterproof by lining them with pitch and cooked in them by dropping heated stones into the water. The most common coiling material was split willow, but sometimes rabbitbrush or skunkbush was used. As pottery-making techniques advanced about AD 550 basket-making declined. The few baskets found here from the Classic Period are not as well made as earlier baskets.

These accomplished potters made vessels of many kinds, including bowls, canteens, ladles, jars, and mugs. Corrugated ware was used mostly for cooking and storage. Elaborately decorated, smooth-surfaced black-on-white wares may have had both ceremonial and everyday uses. Women were probably the potters. Designs tended to be personal and local and most likely were passed down from mother to daughter. Design elements changed over time, which helps archeologists and modern descendants date and possibly track locations of early populations.

Before the Cliff Dwellers

The first Ancestral Pueblo people settled in Mesa Verde (Spanish for "green table") about AD 550. Archeologists call this early period "Basketmaker" to reflect the finely crafted baskets made then. The people farmed corn, beans, and squash, hunted wild animals, and gathered a wide variety of edible and useful plants. They made ingenious tools from stone, wood, and bone, and built pit houses for homes. Pit houses were often clustered as small villages on mesa tops and in cliff alcoves. The people became prolific potters and acquired the bow and arrow, a more efficient hunting weapon than the atlatl, an ancient type of spear thrower.

On the Mesa Tops

Ancestral Pueblo people grew crops and hunted game on the mesa tops. Hand-and-toe-hold trails connected the mesa-top fields to alcove villages and canyons below. The soil was fertile and, except in drought, about as well watered as today. The vegetation is probably about the same. There may have been fewer standing trees and snags. The ancient people cut pinyon and juniper for building materials, firewood, and to clear fields; recent wildfires have left many standing snags.Pit houses People lived in pit houses here from about AD 550 to 750. The pit house was dug into the ground and featured four corner timbers that supported the roof. The firepit had an air deflector to help air circulate through the room. An antechamber might contain storage bins or pits. Some pit houses included a sipapu, a small hole in the floor, which may have had important symbolic meanings.

These were fairly prosperous times for the people, and their population grew. About AD 750 some people began to build houses above ground, with upright walls fashioned of poles and mud. They built their houses one against another in long, curving rows, often with a pit house or two in front. Pit houses would later evolve into kivas. Archeologists call this period "Pueblo," Spanish for town or village, to reflect this architectural change.

Kiva

Kiva comes from the Hopi language and is used in Mesa Verde to refer to round chambers, usually underground, built in or near almost every village or homesite. Most have similar features and were likely used for combined religious, social, and utilitarian purposes. Entry was by ladder through a hole in the center of the roof.The roof, made of timbers, juniper bark, and mud, often formed part of a plaza or public space. In modern Pueblo communities the kiva is still an important ceremonial structure.

By AD 1000, architectural skills had advanced from pole-and-adobe construction to stone masonry. Walls of thick, double-coursed stone often rose two or three stories high and were joined as units of 50 rooms or more. Pottery also evolved, as black drawings on a white background replaced simple designs on a dull gray background. Farming accounted for more of their diet than before, and much mesa-top land was cleared for agriculture.

Farming

At Mesa Verde the people grew their staple crops of squash, corn, and beans in fields scattered across the mesa tops. They worked the soil with digging sticks and often built check dams across draws to catch and hold rain and snow.

Between 1150 and 1300, the Classic Pueblo Period, thousands of people lived on Mesa Verde. Many lived in compact villages of several rooms, often with kivas or courtyards. Carefully shaped building stones, finely built and plastered wall surfaces, and advancing artistry in pottery-making characterize this period. About 1225, another major population shift saw people moving back into the cliff alcoves that sheltered their ancestors centuries before. Why did they make this move? We don't know: perhaps for defense; perhaps for better protection from the elements; perhaps for religious or other reasons. Whatever the events and circumstances, the people began to build the cliff dwellings for which Mesa Verde is most famous.

Most of the cliff dwellings were built from the late 1190s to late 1270s. They range from one-room houses to community centers of about 150 rooms: Cliff Palace and Long House. There is no standard ground plan. Builders fit the structures to the available space. Most walls were single courses of stone, perhaps because alcove roofs limited height and protected the walls from weather erosion. Masonry work varied in quality—rough construction is found alongside walls of well-shaped stones. Many rooms were plastered on the inside and decorated with painted designs.

Exploring Mesa Verde—A World Heritage Site

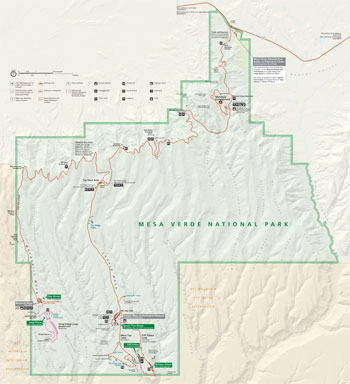

(click for larger map) |

Mesa Verde National Park was created in 1906 to preserve the archeological heritage of the Ancestral Pueblo people, both atop the mesas and in the cliff dwellings below. The park includes over 4,500 archeological sites; only 600 are cliff dwellings. Plan to spend at least a full day discovering the opportunities in the park.

Getting Here Mesa Verde National Park can be reached by air, with daily flights into Cortez and Durango, and from rail terminals in Grand Junction, CO, and Gallup, NM; buses from those points serve Cortez. The park's only entrance and main park road are open 24 hours all year.

Visitor Centers To get the most from your trip, start at the Visitor and Research Center, located just east of the park exit ramp off US 160. Open year-round. Rangers, exhibits, and a bookstore. Chapin Mesa Archeological Museum, 21 miles (45 minutes) from the park entrance, is open all year. Exhibits and dioramas trace the development of the Ancestral Pueblo people.

Interpretive Programs To see Balcony House, Cliff Palace, and Long House, you must join a ranger-guided tour. Tickets are required and are sold at the Visitor and Research Center. Interpretive programs are offered year-round. Check the park website and visitor guide for more information.

Visitor Services Far View Lodge and associated services (lodging and restaurant, cafeteria and gift shop nearby) are available from late April through late October. For reservations contact: Aramark Mesa Verde, PO Box 277, Mancos, CO 81328; www.visitmesaverde.com. Concession bus tours of Chapin Mesa leave from Far View Lodge.

Spruce Tree Terrace, near the Chapin Mesa Archeological Museum, sells food, gifts, and souvenirs year-round.

Camping Morefield Campground, open mid-May to mid-October, has single and group campsites, first-come, first-served. Campsites have tables and fireplaces with grills. Some have utility hookups. There is an RV dump station. Campground services: groceries, carry-out food, firewood, showers, and laundromat. Camping limited to 14 days. Commercial campgrounds are near the park entrance.

Hiking and Backpacking Hike on designated trails only. No overnight backpacking or crosscountry hiking is allowed in the park. Hikers must register at the trailhead or museum for Petroglyph Point and Spruce Canyon trails. Hikers must carry water in summer. Trails can be muddy and slippery after rain; proper footwear is essential. Visitors with health problems should be aware that all trails except Soda Canyon Overlook Trail and Knife Edge Trail include steep elevation changes. Trails are closed by snow in winter.

Bicycles Bicycling is permitted on the park road to Chapin Mesa; use extreme caution due to sharp corners, narrow shoulders, and rocks and large vehicles on the road. Wetherill Mesa Road is closed to bicycles. The Long House Loop, a paved six-mile loop that begins at the Wetherill Mesa kiosk, is open to bicycles.

For Your Safety and Protection Visits to cliff dwellings can be strenuous. Trails are steep and uneven, with steps and ladders to climb. Visiting cliff dwellings or hiking is not recommended for those with heart or respiratory problems. Major cliff dwellings can be seen from overlooks. Parents: Watch carefully for your children's safety, especially near canyon rims and in archeological sites. Do not throw anything into the canyons; there may be people below. Emergency first aid is available; check with a ranger.

Park roads have sharp curves and steep grades. Be alert for falling rocks. Do not park on roadways; use pullouts. Roads and trails may be hazardous in winter; ask for details at the entrance station.

Never leave valuable items unattended and visible in your car. Take valuables with you if possible; lock large items in your trunk. Lock car doors and windows.

Accessibility We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. For information go to a visitor center, ask a ranger, call, or check our website. Overlooks are wheelchair-accessible with assistance. Wheelchairs with wide-rim wheels are recommended. Trails may not meet legal grade requirements.

Regulations Visitors to cliff dwellings must be accompanied by a park ranger during scheduled tours or open hours. • Camp only in the designated campground. • Feeding, capturing, or teasing wildlife, and picking, cutting, or damaging plants are prohibited. • Pets must be physically restrained and are not allowed in public buildings or on trails. • Be careful with fire. One careless match can wipe out the growth of a lifetime. • Firearms regulations are on the park website. • Motor vehicles are allowed only on roadways, pullouts, or parking areas. • Report all accidents or injuries to a park ranger.

Stewardship and Preservation Most cliff dwellings are unexcavated and closed to the public. The Antiquities Act of 1906 and the Archeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 prohibit the excavation, injury, or destruction of any archeological site on federal land and the defacing, destruction, or removal of any object of antiquity in the park. Fines up to $100,000 and imprisonment up to 20 years are possible. Sites in the park are fragile. Please help us protect them for future generations.

Visiting Chapin Mesa and Wetherill Mesa

May through September, visit both Chapin Mesa and Wetherill Mesa. Start at the Visitor and Research Center to plan your trip and purchase tickets for ranger-guided tours of Balcony House, Cliff Palace, and Long House. In winter, Chapin Mesa is open but Wetherill Mesa is closed.

CHAPIN MESA (road open year-round)

Highlights:

• Chapin Mesa Archeological Museum Exhibits, bookstore,

introductory movie.

• Spruce Tree House The best preserved cliff dwelling.

Self-guiding site, spring through fall; free ranger-led tours in winter,

weather and trail conditions permitting.

• Mesa Top Loop Self-guiding auto tour of 600 years of

Ancestral Puebloan architectural development. Short, paved walkways;

most are wheelchair-accessible.

• Cliff Palace Open to ranger-guided hikes during summer

months; tickets required. Hike includes four ladders. Site visible from

overlooks on Mesa Top Loop.

• Balcony House Open to ranger-guided hikes spring through

fall; tickets required. Hike includes climbing long ladder and crawling

through short tunnel.

• Far View Sites Self-guiding trail through a mesa-top

farming community, with five villages and a reservoir. Most walkways are

wheelchair-accessible with help.

• Petroglyph Point and Spruce Canyon trails Loop trails lead

to a petroglyph panel and through scenic wildlife habitat. Hikers must

register at the trailhead or museum.

WETHERILL MESA (open May through September,

weather permitting)

This 12-mile road ends at the Wetherill Mesa kiosk. From there, the Long

House Loop, a paved walking/bicycling trail, leads to overlooks and

archeological sites. • Park your vehicle near the ranger station.

• Stay on trails. • Do not enter closed sites. • Keep

bicycles on the paved trail and park them at trailheads. •

Information, books, and snacks available Memorial Day-Labor Day. No

services rest of season; be prepared!

Highlights:

• Long House Open Memorial Day-Labor Day. Ranger-guided

hikes only; tickets required. Ladders, steep staircase. Visible from

overlook on Long House Loop.

• Step House Open Memorial Day-Labor Day. Self-guiding trail

to site. Alcove, pit houses, cliff dwelling. Rangers are present.

• Badger House Community Self-guiding paved trail through

several communities showing 600 years of changing architectural styles.

Wheelchair-accessible with help.

• Nordenskiold #16 trail Self-guiding trail to a cliff

dwelling overlook.

Source: NPS Brochure (2019)

|

Establishment

World Heritage Site — September 6, 1978 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A City, Asleep: Revisiting and Reevaluating History and Interpretation at Mesa Verde National Park (Andrew Maziarski, 2012)

A Prehistoric Mesa Verde Pueblo and its People: an excerpt from Annual Report, Smithsonian Institution (J. Walter Fewkes, 1916)

An Administrative History, 1906-1970: Mesa Verde National Park (PDF) (HTML edition) (Ricardo Torres-Reyes, 1970)

Anasazi Cultural Parks Study: Assessment of Visitor Experiences at Three Cultural Parks NPS Technical Report NPS/NAUCPRS/NRTR-95/07 (Martha E. Lee and Douglas Stephens, September 1995)

Antiquities of the Mesa Verde National Park: Cliff Palace (HTML edition) Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 51 (Jesse Walter Fewkes, 1911)

Antiquities of the Mesa Verde National Park: Spruce-Tree House (HTML edition) Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 41 (Jesse Walter Fewkes, 1909)

Aquatic Macroinvertebrate and Physical Habitat Monitoring for the Mancos River in Mesa Verde National Park

Aquatic Macroinvertebrate and Physical Habitat Monitoring for Mesa Verde National Park: 2007 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2009/002 (Stacy E. Stumpf and Stephen A. Monroe, July 2009)

Aquatic Macroinvertebrate and Physical Habitat Monitoring for the Mancos River in Mesa Verde National Park: 2008 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2010/033 (Stacy E. Stumpf and Stephen A. Monroe, February 2010)

Aquatic Macroinvertebrate and Physical Habitat Monitoring for the Mancos River in Mesa Verde National Park: 2009 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2011/288 (Stacy E. Stumpf and Stephen A. Monroe, September 2011)

Aquatic Macroinvertebrate and Physical Habitat Monitoring for the Mancos River in Mesa Verde National Park: 2011 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2012/419 (Stacy E. Stumpf and Stephen A. Monroe, December 2012)

Aquatic Macroinvertebrate and Physical Habitat Monitoring for the Mancos River in Mesa Verde National Park: 2012 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2014/684 (Stacy E. Stumpf and Stephen A. Monroe, August 2014)

Aquatic Macroinvertebrate and Physical Habitat Monitoring for the Mancos River in Mesa Verde National Park: 2014 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2016/1061 (Stacy E. Stumpf, September 2016)

Aquatic Macroinvertebrate and Physical Habitat Monitoring for the Mancos River in Mesa Verde National Park: 2015 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2017/1111 (Stacy E. Stumpf, July 2017)

Archeological Excavations in Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, 1950 (HTML edition) Archeological Research Series No. 2 (James A. Lancaster, Jean M. Pinkley, Philip F. Van Cleave and Don Watson, 1950)

Archeological Techniques Used at Mesa Verde National Park (Gilbert R. Wenger, ©Mesa Verde Museum Association, Inc., 1982, digital edition by permission of Mesa Verde Museum Association, all rights reserved)

Are the Ruins Deteriorating Because of Air Pollution? Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado (undated)

Big Juniper House, Mesa Verde National Park—Colorado Archeological Research Series No. 7-C (Jervis D. Swannack, Jr., 1969)

Bird Community Monitoring for Mesa Verde National Park

Bird Community Monitoring for Mesa Verde National Park: 2007 Summary Report, revised NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2011/201 (Jennifer A. Holmes and Matthew J. Johnson, October 2011)

Bird Community Monitoring for Mesa Verde National Park: 2009 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2012/420 (Jennifer A. Holmes and Matthew J. Johnson, December 2012)

Bird Community Monitoring for Mesa Verde National Park: 2012 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2014/623 (Jennifer A. Holmes and Matthew J. Johnson, February 2014)

Bird Community Monitoring for Mesa Verde National Park: 2015 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2016/1065 (Jennifer A. Holmes and Matthew J. Johnson, November 2016)

Circular Relating to Historic and Prehistoric Ruins of the Southwest and Their Preservation (Edgar L. Hewitt, 1904)

Condition Assessment Report: CCC Barracks #5/"Jack Gray Warehouse", Mesa Verde National Park (A. Sayre Hutchison, January 1999)

Condition Assessment Report: Spruce Tree House Alcove Sandstone Arch, Mesa Verde National Park, Mesa Verde, CO (James A. Mason, January 19, 2016)

Contributions to Mesa Verde Archaeology: I — Site 499, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado University of Colorado Studies Series in Anthropology No. 9 (Robert H. Lister and Florence C. Lister, September 1964)

Contributions to Mesa Verde Archaeology: II — Site 875, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado University of Colorado Studies Series in Anthropology No. 11 (Robert H. Lister, November 1965)

Contributions to Mesa Verde Archaeology: III — Site 866, and the Cultural Sequence at Four Villages in the Far View Group, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado University of Colorado Studies Series in Anthropology No. 12 (Robert H. Lister, December 1966)

Contributions to Mesa Verde Archaeology: IV — Site 1086, An Isolated, Above Ground Kiva in Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado University of Colorado Studies Series in Anthropology No. 13 (Robert H. Lister, February 1967)

Contributions to Mesa Verde Archaeology: V — Emergency Archaeology in Mesa Verde National Park Colorad, 1948-1966 University of Colorado Studies Series in Anthropology No. 15 (Robert H. Lister, ed., August 1968)

Deric in Mesa Verde (extract from El Palacio, Vol. 21 No. 9, November 1, 1926)

Effects of Fire on Cultural Resources in Mesa Verde National Park (William H. Romme, Lisa Floyd-Hanna and Linda Towle, February 9, 1993)

Environment of Mesa Verde, Colorado, Wetherill Mesa Studies Archeological Research Series No. 7-B (James A. Erdman, Charles L. Douglas and John W. Marr, 1969)

Excavations in Mancos Canyon, Colorado University of Utah Anthropological Papers No. 35 (Erik K. Reed, August 1958)

Foundation Document, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado (October 2015)

Foundation Document Overview, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado (January 2015)

General Management Plan, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado (May 1979)

Geologic Resource Evaluation Report, Mesa Verde National Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2006/015 (J. Graham, March 2006)

Guide to the Fossils of the Cretaceous Cliff House Sandstone, Mesa Verde National Park (Vincent L. Santucci and Justin S. Tweet, December 2020)

History of Ruins Stabilization at Cliff Palace and Spruce Tree House, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado (Jonathon C. Horn and Susan M. Chandler, 1989)

Impacts of Visitor Spending on the Local Economy, Mesa Verde National Park, 2012 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/EQD/NRR-2013/667 (Philip S. Cook, June 2013)

Integrated Upland Vegetation and Soils Monitoring for Mesa Verde National Park

Integrated Upland Vegetation and Soils Monitoring for Mesa Verde National Park: 2007 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2009/007 (James K. DeCoster and Megan C. Swan, July 2009)

Integrated Upland Vegetation and Soils Monitoring for Mesa Verde National Park: 2008 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2009/019 (James K. DeCoster and Megan C. Swan, December 2009)

Integrated Upland Vegetation and Soils Monitoring for Mesa Verde National Park: 2009 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2011/172 (James K. DeCoster and Megan C. Swan, June 2011)

Integrated Upland Vegetation and Soils Monitoring for Mesa Verde National Park: 2010 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2013/513 (James K. DeCoster and Megan C. Swan, July 2013)

Integrated Upland Vegetation and Soils Monitoring for Mesa Verde National Park: 2011 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2013/517 (James K. DeCoster and Megan C. Swan, July 2013)

Integrated Upland Vegetation and Soils Monitoring for Mesa Verde National Park: 2012 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2014/696 (James K. DeCoster and Megan C. Swan, August 2014)

Interpretive Prospectus, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado (1993)

Junior Ranger Booklet, Mesa Verde National Park (2018; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Activity Book: Mesa Verde National Park (2024)

Mesa Verde National Park Online Junior Ranger Booklet (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Line Officer Guidelines to Incoming Overhead Team Incident Commander, Mesa Verde National Park Colorado (October 31, 1989)

Livestock Removal Environmental Assessment, Mesa Verde National Park (April 2018)

Long Mesa Fire 1989 — Fire Effects and Cultural Resources: An Annotated Bibliography (Faith L. Duncan, September 1990)

Long Mesa Fire 1989 — Fire Effects on Pollen: An Evaluation (Suzanne K. Fish, 1989)

Master Plan (Draft), Mesa Verde National Park (September 1975)

Measuring Visibility From Far View, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado (undated)

Mesa Verde Museum Exhibit Guide (1987)

Mesa Verde National Park (United States Railroad Administration, 1919)

Mesa Verde National Park Historic Furniture Research Project (Patti Bell, August 2024)

Mesa Verde National Park: Portfolio (undated)

Mesa Verde National Park: Shadows of the Centuries (Duane A. Smith, 1988, rev. ed. 2002)

Mesas, Cliffs, and Canyons: The University of Colorado Survey of Mesa Verde National Park, 1971-1977 Mesa Verde Research Series No. 3 (Jack E. Smith, ©Mesa Verde Museum Association, Inc., 1987, digital edition by permission of Mesa Verde Museum Association, all rights reserved)

Monitoring of Air Chemistry and Sandstone Masony Degradation at Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado (Donald A. Dolske and William T. Petuskey, c1985)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Mesa Verde National Park Headquarters, Museum, Post Office, Ranger Dormitory, Superintendents Residence and Community Building (Laura Soullière Harrison, 1986)

Paleontological Resource Inventory (Non-Sensitive Version), Mesa Verde National Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/MEVE/NRR-2017/1550 (G. William M. Harrison, Justin S. Tweet, Vincent L. Santucci and George L. San Miguel, November 2017)

Proceedings of the Anasazi Symposium 1981 (Jack E. Smith, ed., ©Mesa Verde Museum Association, Inc., 1983, digital edition by permission of Mesa Verde Museum Association, all rights reserved)

Park Newspaper (InterPARK Messenger): c1990s • 1992

Park Newspaper

2007: Summer/Fall • Winter

2008: Early Spring • Late Spring • Summer/Fall

2009: Summer/Fall • Winter

2010: Spring • Summer/Fall

2011: Summer/Fall • Winter

2012: Summer/Fall • Winter

2013: Spring • Summer/Fall • Winter

2014: Spring • Summer/Fall • Winter

2015: Spring • Summer/Fall • Winter

2016: Spring • Summer/Fall • Winter

2017: Spring • Summer/Fall • Winter

2018: Spring • Summer/Fall • Winter

2019: Spring • Summer/Fall • Winter

2020: Summer • Winter/Early Spring

Wetherill Mesa: Summer 2015 • Fall 2015 • 2016 • 2017 • 2019

Plant Salvage Report, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado (Patty Cascio, September 15, 2009)

Prehistoric Settlement and Physical Environment in the Mesa Verde Area University of Utah Anthropological Papers No. 53 (Joyce Herold, November 1961)

Proceedings of the Anasazi Symposium 1991 (Art Hutchinson and Jack E. Smith, eds., ©Mesa Verde Museum Association, Inc., c1993, digital edition by permission of Mesa Verde Museum Association, all rights reserved)

Proposed Mesa Verde National Park Wilderness: Final Environmental Impact Statement (1974)

Report of the Acting Superintendent of the Mesa Verde National Park to the Secretary of the Interior: 1911 (HTML edition) (Richard Wright, 1911)

Report to the Secretary of the Interior by the Superintendent of the Mesa Verde National Park: 1915 (HTML edition) (Thomas Rickner, 1915)

Reports of the Superintendent of the Mesa Verde National Park and J. Walter Fewkes, in Charge of Excavation and Repair of Ruins to the Secretary of the Interior: 1909 (HTML edition) (Hans M. Randolph and J. Walter Fewkes, 1909)

Spruce Tree House Alcove Arch Stabilization Newsletter 1 (December 2021)

Spruce Tree House Alcove Arch Stabilization Environmental Assessment, Mesa Verde National Park (March 2023)

Strategic Plan: Mesa Verde National Park, October 1, 2001-September 30, 2005 (2000)

Surficial Geologic Map of Mesa Verde National Park, Montezuma County, Colorado U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 3224 (Paul E. Carrara, 2012)

The 1926 Re-Excavation of Step House Cave, Mesa Verde National Park Mesa Verde Research Series No. 1 (Jesse L. Nusbaum, ©Mesa Verde Museum Association, Inc., 1981, digital edition by permission of Mesa Verde Museum Association, all rights reserved)

The Archeological Survey of Wetherill Mesa Archeological Research Series Number 7-A (Alden C. Hayes, 1964)

The Colorado Cliff Dwellings Association (David L. Hartman, extract from The Denver Westerners Roundup, Vol. 34 No. 4, July-August 1978; ©Denver Posse of Westerners, all rights reserved)

The Mesa Verde Museum (Richard M. Howard, ©Mesa Verde Museum Association, Inc., 1968, digital edition by permission of Mesa Verde Museum Association, all rights reserved)

The Mule Deer of Mesa Verde National Park Mesa Verde Research Series No. 2 (Gary W. Mierau and John L. Schmidt, eds., ©Mesa Verde Museum Association, Inc., 1981, digital edition by permission of Mesa Verde Museum Association, all rights reserved)

The Road Inventory for Mesa Verde National Park (August 2000)

Traffic Safety Study: Far View/Weatherill, "Three-Way", "Four-Way", Mesa Verde National Park Final Report (Lee Engineering, April 4, 1996)

Transportation Study, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado (April 2000)

Two Chimaeroid Egg Case Remains from the Late Cretaceous, Mesa Verde National Park, Colorado, USA (G. William M. Harrison IV, James I. Kirkland, Jan Fischer, George San Miguel, John R. Wood and Vincent L. Santucci, from New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin No. 82, 2021, ©New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, all rights reserved)

Vegetation Classification and Distribution Mapping Report: Mesa Verde National Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SCPN/NRR—2009/112 (Kathryn A. Thomas, Monica L. McTeague, Lindsay Ogden, M. Lisa Floyd, Keith Schulz, Beverly Friesen, Tammy Fancher, Robert Waltermire and Anne Cully, May 2009)

Visitor Study: Summer 2012, Mesa Verde National Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/EQD/NRR—2013/664 (Ally Begly, Gail A. Vander Stoep, Yen Le and Steven J. Hollenhorst, May 2013)

Wetherill Mesa Design Directive, Mesa Verde National Park (December 1969)

Water Quality Monitoring for the Mancos River in Mesa Verde National Park

Water Quality Monitoring for the Mancos River in Mesa Verde National Park: 2010 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2012/351 (Stephen A. Monroe, Clay Bliss, Melissa Dyer and Kelly Lawrence, July 2012)

Water Quality Monitoring for the Mancos River in Mesa Verde National Park: 2011 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2013/567 (Melissa Dyer and Stephen A. Monroe, September 2013)

Water Quality Monitoring for the Mancos River in Mesa Verde National Park: 2012–2013 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2016/1221 (Melissa Dyer, Stephen A. Monroe and Stacy E. Stumpf, May 2016)

Water Quality Monitoring for the Mancos River in Mesa Verde National Park: 2014 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SCPN/NRDS—2017/1132 (Melissa Dyer and Stacy Stumpf, November 2017)

meve/index.htm

Last Updated: 19-Mar-2025