|

Virgin Islands National Park Virgin Islands |

|

NPS photo | |

A Treasure Trove of Discoveries

Time is something to be ignored when you visit Virgin Islands National Park and Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument. Pay no attention to your wristwatch; better yet, don't even wear one. Adjust yourself instead to St. John's slower pace. Forget about trying to cram too many things into your visit. Ignore this advice and you will depart less enriched than those who have made a successful transition to island time.

Rumor has it that pirates buried fortunes throughout this Caribbean area. Today's island visitors find treasures of greater value than gold and silver. A wealth of beaches, coral reefs, plantation ruins, and diverse plants and animals is awaiting discovery here. This national park is indeed a treasure trove filled to the brim. You will be rewarded!

The Island of St. John

Throughout history people seeking paradise on Earth have traveled—or dreamed of traveling—to a tropical island where they could find beauty, refreshment, and refuge. Today just over half of the small, rugged volcanic island of St. John is protected as a natural paradise within Virgin Islands National Park. Among the earthly delights are tropical forests, wildlife, wildflowers, and breathtaking views. Just offshore, dazzling natural riches are preserved in the marine areas. Combined, the land and waters of St. John are, in many ways, a world apart.

As on most Caribbean islands, the natural world of St. John has undergone tremendous changes. Forests were cleared over almost all of St. John for sugar plantations, farms, and houses in the 1700s and 1800s. Foreign trees and shrubs, introduced to provide food or medicines, invaded the native forests, and by the early 1900s no sizable original stands were left. People also introduced new animals that have devastated the natural environment here. The mongoose, for example, eats eggs of ground-nesting birds and sea turtles.

But today, with an ample part of St. John's natural resources managed by the national park, the tropical forest and much of the island's native wildlife are protected. The island's variety of over 800 species of plants includes the teyer palm, St. John's only native palm tree; the bay rum tree, whose aromatic leaves once provided the oil for world-famous bay rum cologne; and rare, brilliantly colored wild orchids. St. John is a sanctuary for animals as diverse as corals, sea turtles, and reef fish; insect- and fish-eating bats; frogs; gecko, anole, and iguana lizards; and birds. Over 50 species of tropical birds breed on St. John, including the bananaquit, black, parrot-like smooth-billed ani, and two species of Caribbean hummingbirds. Many warblers and other birds seen in the continental United States in summer, known as neotropical migrants, spend the winter in the park's dense forests. On St. John island life flourishes.

Scurrying Lizards

Anole lizards, geckos, and iguanas abound. Male anole lizards extend colorful dewlaps and do pushups in territorial and courtship displays.Bananaquit

The everpresent bananaquit is the official bird of the Virgin Islands. With its long, downward-curving bill it feeds on the nectar of tropical flowers.A Richness in Plant Life

St. John's forests vary from moist subtropical forests of the interior mountains to semi-arid cactus scrublands on south-facing slopes and rocky, windswept peninsulas. They host over 800 species of trees and other plants. Inviting park trails wind through forests that are now a mix of native and introduced species.Only at Night

Largest of the island's blossoms, the vanilla-scented, night-blooming cereus is pollinated by bats and may be seen, true to its name, only at night.

Beaches

White beaches of the Virgin Islands have a well-deserved reputation for being some of the world's most beautiful. These picture-postcard beaches fringe Hawksnest Bay, Trunk Bay, Cinnamon Bay, Saltpond Bay, and other sheltered coves.

Sand, the key ingredient to a beach, is brought to the island's shore by waves, tides, and currents. Where does that sand come from? Primarily from two sources within a bay: from marine algae that grow just offshore and from living coral reefs. Both, when broken down into tiny fragments, make sand. Without the algae and the reefs, in time the ready supply of sand would disappear, as would the beaches.

Reefs also serve as the first line of defense for the beaches by reducing the full force of incoming waves that otherwise would cause serious erosion. On stretches of St. John's rugged coast that lie exposed and unprotected by the reefs, the shoreline is made up of cobbles and bare rocks.

Except for sunbathers and swimmers, the beaches can appear to be lifeless. Not so.

Sandpipers and other shorebirds visit the beaches and probe along the water's edge in the sand for small crabs, mollusks, and other burrowing creatures that live off morsels of food the waves bring in. Sea turtles spend most of their lives in tropical seas, but must come ashore to lay their eggs in sand. Beaches on St. John and throughout the world are essential to the survival of these critically endangered animals.

Sea Turtles

Two endangered sea turtles, the hawksbill and the green, are commonly seen in St. John waters. The hawksbill comes ashore on St. John beaches to dig its nest and lay eggs. After burying eggs in the warm sand, the female returns to the offshore waters. The hatchlings will instinctively turn toward the sea. Despite laws protecting them in many countries, sea turtles are still hunted In some areas for their shells and meat.Migrating Thousands

An island riddle: "Ah lib on Ian' an' walk about. But always home in or out." Give up? It's the soldier crab who lives in abandoned shells, mostly the West Indian top shell, locally called whelk. Found all over the island, thousands of them come down to the beach in annual August migrations to breed and lay eggs at the water's edge.

Nearshore Waters

Ecologically important mangrove communities edge parts of the island, between terrestrial and marine ecosystems. Red mangroves with their distinctive prop roots occur in shoreline areas where reefs or bays protect them from waves. Undersea meadows of seagrass beds also prefer these calmer waters.

Mangroves and seagrass beds provide food and shelter to an astonishing variety of organisms.

Submerged prop roots of the mangroves are encrusted with a colorful assortment of algae, tunicates, sponges, anemones. from predators, juvenile snappers, grunts, groupers, doctorfish, and many other species find shelter amid the maze of roots. When older and larger, many of them venture out to spend the rest of their lives on the coral reef.

Turtle grass and manatee grass predominate in the seagrass beds. Their gently undulating blades provide food for sea turtles, fish, and sea urchins. Also roaming throughout this area are unusual animals like sea cucumbers, batfish, spotted eagle rays, goldspotted eels, and queen conch.

Mangrove Nurseries

Mangrove swamps in the park's coastal areas are productive nurseries for sea life. In turn, young fish, juvenile lobsters, and other organisms that live in the maze of underwater mangrove roots provide food for green herons, other birds, and large fish.Schools of Grunts

French grunts are one of many reef fish that begin their lives hiding in the seagrass beds, where they eat crabs, shrimp, and marine worms. Adult grunts hover in huge schools over reefs by day, but each night they leave the safety of the reefs and feed again among undersea grasses.

Coral Reefs

"Magical." "I always see something different." "Unbelievable colors and shapes." These words from snorkelers and divers describe the fascinating underwater world of the coral reefs. Kaleidoscopic changing colors, the variety of unusual shapes, and the diversity of coral, fish, and other life combine to make your exploration of the reef a priceless, never-to-be-forgotten experience.

Snorkeling is an excellent way to enjoy this underwater wonderland. Be observant. Fish, lobsters, and feather duster worms disappear and reappear within mere seconds in one location!

Reefs have been compared to underwater cities. Alleys, streets, and cul-de-sacs twist between high-rise coralline structures in which a vacant dwelling is virtually nonexistent. Wispy cleaner shrimp dance about to attract their more-than-willing finned hosts. By day moray eels, spiny lobsters, deflated porcupinefish, and crimson squirrelfish hole up in reef crevices.

At night, they come out to feed, and the city is transformed into an eerie nether world where octopuses slither about and parrotfish seek protection, resting in their veil-like mucus cocoons. Coral polyps emerge from their stony skeletal homes, stretching their tentacles out to feast on tiny plankton.

Throughout day and night, lacy-looking sea fans, sea whips, sea plumes, and other soft corals undulate in the current.

They create the appearance of an underwater garden, but nothing could be farther from the truth. This is a garden that cannot afford even the slightest damage. The fastest growing corals grow only two to three inches per year, and large brain corals are hundreds of years old. A carelessly placed anchor or flipper, or excessive sediments running off newly cleared slopes can devastate reef life. Virgin Islands National Park and Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument preserve what is fast becoming a disappearing natural phenomenon worldwide.

Coral City Builders

A tiny coral polyp shown here at over 1,000 times its size is mostly soft stomach, stinging tentacles, and mouth surrounded by a hard limestone skeleton. Working together in huge colonies, these simple animals have built all the world's coral reefs.Beach Builders

While feeding on algae that grow on coral, parrotfish ingest some of the hard coral skeletons. Later, they excrete the undigested calcareous matter. Each year as much as a ton of sand per acre may pass through the intestinal tracts of reef fish.Reefs Worldwide

Coral reefs grow in tropical waters where sea temperatures are over 70°F throughout the year. They are all at risk from climate change and invasive species. Unprotected reefs also face damage from water pollution, sedimentation, boat anchors, and overfishing.Snapping Shrimp

Anything but silent, the underwater world gets punctuated by many sounds. Looking for protection at the base of a ringed anemone, the red snapping shrimp defends its home and stuns prey by snapping its enlarged claw to make a pistol-like sound easily heard by snorkelers.Fish-cleaning Fish

At reef cleaning stations, small fish like sharknose gobies eat parasites from larger fish like Nassau groupers, who stop by and sometimes even line up for this special service.

St. John's Historical Heritage

A Cultural Crossroads

Virgin Islands' history can be traced back 3,000 years. Archeological work shows that people who had moved north in canoes from South America lived on St. John as early as 710 BCE (before common era). They hunted and gathered food, mostly from the sea. Like its other island neighbors, by 100 CE (common era) St. John was home to a small population of Taino who lived in sheltered bays, made pottery, and practiced agriculture.

Columbus may have named the islands in 1493, but no European settlements were in place until the 1720s. Attracted by the lucrative prospects of cultivating sugar cane, the Danes took formal possession in 1694 and raised their flag in 1718, establishing the first permanent European settlement on St. John, at Estate Carolina in Coral Bay.

Rapid expansion followed, and by 1733 virtually all of St. John was planted in sugar cane and cotton. As the plantation economy grew, so did the demand for slaves. Many captured in West Africa were tribal nobles and former slaveholders themselves. They revolted in 1733, killing European families throughout the island. The Africans controlled St. John for six months and were finally subdued not by Danes but by French troops from Martinique.

Emancipation of enslaved people in 1848 and a drop in population contributed to the decline of St. John's plantations. By the early 1900s cattle and subsistence farming and bay rum production were the main occupations.

Century of Change "Of white people there are only a Danish official who is stationed there as a local judge and Chief of Police, and a few missionaries, who attend to the spiritual welfare of the 900 negro inhabitants of the island." A few decades after this 1900 report, sleepy St. John caught the public eye. By the 1930s word of this Caribbean paradise spread, and the tourist industry took off. In 1956 Rockefeller interests bought land, giving it to the federal government for a national park. In 1962 the park was enlarged to include 5,650 acres of adjacent offshore marine habitat. In 2001 Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument was created to protect more than 12,000 acres of underwater habitat.

Planning for the Future Today the park works with local, stateside, and Caribbean-wide conservation-minded interests to preserve the area's natural and cultural resources. In recognition of its outstanding natural resources, the park is a part of the international network of biosphere reserves. As the future unfolds, the park and the territory strive to ensure the preservation of America's tropical treasures.

Taino People

At one time, Taino villages lined the coast of St. John. Archeologists have studied such sites to learn about these people who once lived throughout the West Indies. The Taino welcomed Christopher Columbus when he arrived in the new world. But the natives were decimated by European diseases, and from enslavement and overwork during Spanish colonization.Annaberg Sugar Mill

Remnants of the windmill, horse mill, and factory buildings tell the story of sugar production at Annaberg.At Work and Play

Sugar cane is no longer harvested on St. John although it is on some islands. A St. Johnian makes traditional market baskets out of local hoop vine. Steel bands, mocko jumbies and other masqueraders celebrate "mas" each July 4 in a dazzling carnival parade on St. John.

Exploring Virgin Islands

Park Travel Advisory

When you visit Virgin Islands National Park and St. John, be aware of

these local customs and park regulations and safety tips (see below).

• When walking in town, both men and women should wear a T-shirt or

other coverup. • Private property exists within the park boundary.

Please respect land owners' rights; do not trespass. • All driving

is on the leftside of the road throughout the Virgin Islands. Mountain

roads are narrow and winding; drive carefully and observe speed limits.

• Practice safe boating. Watch for unmarked reefs, other boats, and

swimmers. Divers and snorkelers must fly a diver's flag if outside boat

exclusion areas; stay 100 feet away. • You must have a passport to

visit the British Virgin Islands or other Caribbean islands. • An

island courtesy includes greeting others with a cheerful "Good-day."

US Virgin Islands

American Tropical Treasures

The three main US Virgin Islands offer tropical pleasures. St. John, with Virgin Islands National Park and Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument, is least developed. Next door is the tourist mecca of St. Thomas, with its cruise ship harbor of Charlotte Amalie. St. Croix has quaint towns and pastoral landscapes.

Island Hopping Ferries run between Cruz Bay, St. John, St. Thomas, and the British Virgin Islands. Red Hook ferry runs hourly from 6 am (departing St. John) to midnight (departing Red Hook); Charlotte Amalie ferry runs less often. Water taxis are available. Flights connect St. Thomas and St. Croix.

Services and Accommodations Taxis and safari buses operate on St. Thomas and St. John. You can find land, sea, air, and underwater tours and rent boats and snorkeling and scuba gear. Major services are available. Lodging ranges from campgrounds to luxury hotels; reserve ahead. Peak season is December through April. For more information contact the Virgin Islands Department of Tourism, www.usvitourism.vi.

National Parks on St. Croix Christiansted National Historic Site preserves the architecture of Christiansted from the 1700s and 1800s when these islands were a Danish colony. Daytrips to the island and coral reefs of Buck Island Reef National Monument can include snorkeling, glass-bottom boat tours, and hiking. Salt River Bay National Historical Park and Ecological Preserve is the only site under the US flag where Columbus's crew made landfall. For more information contact Christiansted National Historic Site, www.nps.gov/chri.

Virgin Islands National Park and St. John

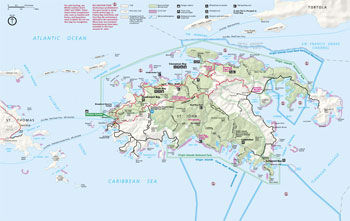

Over half of St. John is national parkland; the rest is small towns, shops, homes, and territorial or private lands. The national park and Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument protect offshore waters.

Touring the Park

(click for larger map) |

Cruz Bay Visitor Center Start here for information, publications, activities schedules, exhibits, and gift shop. It is open daily except Thanksgiving Day, December 25, and July 4. Staff can help you plan your visit, including hikes, historical tours, snorkeling, and camp-ground programs. Advance registration and fees are required for some events or activities. Call the park or check the park website.

Getting Around Two-hour guided island tours begin and end at the public ferry dock in Cruz Bay. They stop at beach and hillside overlooks and at remnants of Annaberg and other sugar plantations. Taxis and safari buses serve north shore beaches.

Beautiful Beaches St. John's beaches are ideal for sunbathing, and the clear turquoise water is perfect for swimming and snorkeling. The beach at Trunk Bay has a bathhouse, snack bar, and snorkel gear rentals.

Cinnamon Bay has restrooms, a bathhouse, and a family-friendly restaurant. The sports center rents snorkel gear, kayaks, and paddleboards. It can arrange day sailing, snorkeling, scuba diving lessons, and excursions. Contact info@cinnamonbayresort.com.

Hawksnest Bay has change rooms and is the closest park beach within driving distance of Cruz Bay. Roads and trails go to remote beaches. Picnic areas have tables, grills, and restrooms, and are wheelchair-accessible.

Underwater Explorations Trunk Bay has a 225-yard underwater snorkeling trail marked by signs that identify coral reef life. Fish can appear tame, but do not feed them; they need a natural diet to survive. Snorkel shops are located at Honeymoon Beach, Trunk Bay Beach, Cinnamon Bay Beach, and Maho Bay Beach. Dive shops rent snorkel and scuba gear and run trips to offshore reefs.

Boating and Sailing The US and British Virgin Islands offer hidden harbors, beaches, and dive spots. Charter operations provide excursions: a half day to many weeks; power or sail; crew or uncrewed. Caneel, Francis, and Maho bays are popular for overnight stays. Be sure to contact the park about moorings and their use. Boats are limited to 30 nights in park waters during a 12-month period. Restrictions include 7 nights per bay. Rent powerboats in Cruz Bay or Coral Bay on St. John or in Red Hook on St. Thomas.

Fishing You may fish in Virgin Islands National Park with a rod and reel or hand line, except in designated swim zones and when tied to a mooring ball. Bait fish may be taken by nets; restrictions apply. Spear guns and commercial fishing, including chartered trips and fly-fishing excursions, are prohibited. • Fishing is not allowed in Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument, except for bait fishing in Hurricane Hole and blue runner (hardnose) fishing at designated yellow mooring locations near Cabritte Horn Point. You must have a special permit for each activity.

Hiking Trails range from easy walks to difficult climbs, from well-maintained to brushy. Ask for a trail guide at the visitor center. On guided hikes of Reef Bay Valley (five hours) you can see petroglyphs (rock carvings) and the remains of St. John's last active sugar mill. In winter the Francis Bay Trail offers excellent birding of the nearly 160 species of resident and neotropical birds, including the white-cheeked pintail duck and mangrove cuckoo. Stay on trails. Protect yourself from sun, insects, and thorny vegetation: wear a hat and loose clothing and use sunscreen and insect repellent.

Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument

Presidential proclamation created this underwater monument from 12,708

acres of federal submerged lands. Explore it by kayak, paddleboard, or

charter vessel. Snorkel the bays of Hurricane Hole to discover the

unique mangrove ecosystem that is a nursery for young marine animals and

home to brilliantly colored brain corals, sponges, cushion sea stars,

and healthy seagrass beds.

Facilities and Services

Campgrounds Camping is restricted to Cinnamon Bay Campground. Accommodations include bare tent sites, tent-covered platforms, eco tents, and cottages. Prepared sites and cottages have cooking supplies and linens. A store has food, supplies, and cafeteria. Reservations are recommended. For more information, contact info@cinnamonbayresort.com.

Accessibility We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. For information go to the visitor center, ask a ranger, call, or check the park website.

Emergencies and medical services, call 911

A Different Time

The Virgin Islands are in the Atlantic time zone. In winter the time here is one hour later than eastern standard time. In summer, when the US goes on daylight-saving time, the time is the same.Many Points of View

Views from each pullout seem more spectacular than the last. The scent of bay rum trees at higher elevations like Bordeaux Mountain, elevation 1,277 feet, recalls past times when the leaves were harvested to produce St. John's famous Bay Rum Oil. You can see the British Virgin Islands from Centerline Road (Route 10).Sugar Plantations

Explore remnants of old sugar plantations at Annaberg on Leinster Bay Road; Catherineberg just off Centerline Road; and Cinnamon Bay.

Safety and Regulations

Protect yourself from overexposure to tropical sunlight. If you burn easily, stay indoors or in the shade between 10 am and 2 pm. Wear a hat, sunglasses, and protective clothing like a rash guard. If you need sunscreen, use a kind that is reef-safe.

Some plants are toxic or poisonous and can cause rashes and illness. Do not touch or taste any unfamiliar plant.

Feral donkeys bite and kick. Do not feed or approach them.

Pets must be leashed and attended. They are not allowed on beaches, in the campground, or in picnic areas. Service animals are welcome.

Large, shore-breaking waves—especially in winter on the North Shore—are dangerous. Use extreme caution when entering or leaving the water when surf is high. Body surfing is not recommended. Never swim or snorkel alone. For your own and the reef's protection, do not stand on reefs or touch or scrape coral and other marine life when snorkeling or scuba diving.

Scuba diving is not allowed in designated boat channels, shipping lanes, near docks, and in boat exclusion areas. Personal watercraft and waterskiing are not allowed in park and monument waters.

Smoking, fires, and n!ass bottles are not allowed on the beach.

Virgin Islands territorial law prohibits public nudity.

Defacing, breaking, or removing any natural or historical features on the island or in the water is prohibited.

Do not climb on old walls and structures. They crumble easily, and you can be seriously injured.

Lock valuables in your vehicle or take them with you.

It is illegal to dump litter in park waters or on land.

For firearms and other regulations check the park website.

Source: NPS Brochure (2019)

|

Establishment Virgin Islands National Park — August 2, 1956 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Cooperative Multiagency Reef Fish Monitoring Protocol for the U.S. Virgin Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem, v. 1.00 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SFCN/NRR—2013/672 (David R. Bryan, Andrea J. Atkinson, Jerald S. Ault, Marilyn E. Brandt, James A. Bohnsack, Michael W. Feeley, Matt E. Patterson, Ben I. Ruttenberg, Steven G. Smith and Brian D. Witcher, June 2013)

A Timeline of TaÍno Development in the Virgin Islands (Ken Wild, 2013)

A Unique Coral Community in the Mangroves of Hurricane Hole, St. John, US Virgin Islands (Caroline S. Rogers, extract from Diversity, Vol. 9(29), 2017)

An Archaeological and Historical Investigation of a 19th Century Leprosarium at Hassel Island, St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands (Amanda Marie Barton, December 2012)

An Introduction to the Mangrove Lagoon (A.R. Teytaud, 1970)

Annaberg: An Updated Survey of the Annaberg Factory Complex, Virgin Islands National Park, St. John, USVI (David W. Knight, 2001)

Brown Bay, St. John, US Virgin Islands: Uncovering an Eighteenth Century Landscape and its Inhabitants though Archival and Archeological Research (Marie Veisegaard Olsen and Agnes Elbæk Wraae, 2009)

Caneel Bay Area Redevelopment and Management Environmental Assessment, Virgin Islands National Park (January 2023)

Caneel Bay Area Redevelopment and Management Environmental Assessment Newsletter, Virgin Islands National Park (January 2023)

Chikungunya outbreak in the Caribbean and South America — Update (June 16, 2014)

Classified Structure Field Inventory Reports

Annaberg Historic District (c1981)

Brown Bay Plantation Historic District (c1981)

Dennis Bay Historic District (c1981)

Hermitage Plantation Historic District (c1981)

Jossie Gut Historic District (c1981)

L'Esperance Historic District (c1981)

Liever Marches Bay Historic District (c1981)

Liind Point Fort (c1981)

More Hill Historic District (c1981)

Reef Bay Great House Historic District (c1981)

Reef Bay Sugar Factory Historic District (c1981)

Rustenberg Plantation South Historic District (c1981)

Trunk Bay Sugar Factory (c1981)

Coastal vulnerability assessment of Virgin Islands National Park (VIIS) to sea-level rise USGS Open-File Report 2004-1398 (Elizabeth A. Pendleton, E. Robert Thieler and S. Jeffress Williams, 2005)

Coral Bleaching and Disease Deliver "One - Two Punch" to Coral Reefs in the U.S. Virgin Islands (Matt Patterson, Caroline Rogers, Bane Schill and Jeff Miller, October 2006)

Coral diseases following massive bleaching in 2005 cause 60 percent decline in coral cover and mortality of the threatened species, Acropora palmata, on reefs in the U.S. Virgin Islands USGS Fact Sheet 2008-3058 (Caroline S. Rogers, Jeff Miller and Erinn M. Muller, June 2008)

Coral Reefs in the U.S. National Parks: A Snapshot of Status and Trends in Eight Parks NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/NRR-2009/091 (Nash C. V. Doan, K. Kageyama, A. Atkinson, A. Davis, J. Miller, J. Patterson, M. Patterson, B. Ruttenberg, R. Waara, L. Basch, S. Beavers, E. Brown, P. Brown, M. Capone, P. Craig, T. Jones and G. Kudray, April 2009)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory, Annaberg Sugar Factory, Virgin Islands National Park (2010)

Diverse coral communities in mangrove habitats suggest a novel refuge from climate change (K.K. Yates, C.S. Rogers, J.J. Herlan, G.R. Brooks, N.A. Smiley and R.A. Larson, extract from Biogeosciences, Vol. 11, 2014)

Ecological Research in the Virgin Islands: Historical and Administrative Background (O. Marcus Buchanan, April 24, 1973)

Economic Impact Analysis for the Virgin Islands National Park: Final Report (1981)

Foundation Document, Virgin Islands National Park/Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument, U.S. Virgin Islands (December 2016)

Foundation Document Overview, Virgin Islands National Park/Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument, U.S. Virgin Islands (January 2016)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Virgin Islands National Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2010/226 (K. Hall and K. KellerLynn, July 2010)

Geology of St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands USGS Professional Paper 1631 (Douglas W. Rankin, 2002)

Guía Para Identificar los Corales Someros del Gran Caribe (Ernesto Weil y Héctor Ruiz, 2003)

Guide for the Identification of the Shallow Water Corals of the Wider Caribbean (Ernesto Weil and Héctor Ruiz, 2003)

Herpetofaunal Inventories of the National Parks of South Florida and the Caribbean: Volume II. Virgin Islands National Park US Geological Survey Report Series 2005-1301 (Kenneth G. Rice, J. Hardin Waddle, Marquette E. Crockett, Raymond R. Carthy and H. Fanklin Percival, 2005)

Historic Architecture of the Virgin Islands Selections from the Historic American Buildings Survey No. 1 (February 1966)

Historic Preservation in the U.S Virgin Islands: Preserving our Past for our Future for 2016-2021 — The U.S. Virgin Islands Statewide Historic Preservation Plan (Virgin Islands State Historic Preservation Office, September 2016)

Historic Resource Study: St. John Island ("the quiet place"), Virgin Islands National Park with Special Reference to Annaberg Estate, Cinnamon Bay Estate (Charles E. Hatch, Jr., January 1972)

Historic Structure Report: Creque Marine Railway Head House and Residence, Virgin Islands National Park (Julie Duggins, Janet Rozick, Elayne Anderson, Helen Juergens, Christopher Cheny, Ileana Olmos, Chris Baker and Brett Brumbaugh, January 28, 2021)

Historic Structures Report (Part I) Architectural Data Section: Reef Bay Great House, Reef Bay Estate, Virgin Island National Park (Frederik C. Gjessing, November 1968)

Historic Structures Report (Part I) / History Data Section: Reef Bay ("Par Force") Estate Great House and Reef Bay Sugar Factory, Virgin Islands National Park (Charles E. Hartch, Jr., June 1, 1970)

Impact of Visitor Spending and Park Operations on the Regional Economy: Virgin Islands National Park (Jane Israel, October 2004)

Indigenous Gold from St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands: A Materials-Based Analysis (©Stephen E. Jankiewicz, Master's thesis, 2016)

Initial Inventory of Three Permanent Forest Plots in the Virgin Islands National Park Biosphere Reserve Research Report No. 27 (John E. Earhart, Anne E. Reilly an Matt Davis, 1988)

Investigations at Cinnamon Bay, St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands and Social Ideology in the Virgin Islands as Reflected in Pre-Columbian Ceramics (Ken S. Wild, 2001)

Management of Natural Resource Information for the Virgin Islands National Park and Biosphere Reserve Special Biosphere Reserve Report (Island Resources Foundation, 1988)

Marine and Terrestrial Ecosystems of the Virgin Islands National Park and Biosphere Reserve Biosphere Reserve Report No. 29 (Caroline S. Rogers and Robert Teytaud, September 1988)

Measuring, Interpreting, and Responding to Changes in Coral Reefs: A Challenge for Biologists, Geologists, and Managers (Caroline S. Rogers and Jeff Miller, 2016)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Christiansted Historic District (Russell Wright and Thomas Richards, May 22, 1976)

Caneel Bay (Cinnamon Bay Plantation) (Frederick C. Gjessing, April 1976)

Cathrineberg, Jockumsdahl, Herman Farm (Hammer Farm Plantation) (Frederick C. Gjessing, February 1976)

Historic Resources of Virgin Islands National Park (partial inventory, Historic & Architecture) (Frederick C. Gjessing, August 2, 1978)

Lameshur Plantation (Frederick C. Gjessing, June 1976)

Mary Point Great House and Factory (Fredrick C. Gjessing, November 1975)

Petroglyph Site (Lindsay Christine Beditz, June 28, 1978)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Virgin Islands National Park and Virgin Islands Coral Reef National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/VIIS/NRR-2022/2408 (Danielle E. Ogurcak, Maria C. Donoso, Alain Duran, Rosmin S. Ennis, Tom Frankovich, Daniel Gann, Paulo Olivas, Tyler B. Smith, Ryan Stoa, Jessica Vargas, Anna Wachnika and Elizabeth Whitman, June 2022)

Observations of the Architecture at Reef Bay Estate and Fortberg Hill, St. John, Virgin Islands (F.C. Gjessing, November 3, 1954)

Phytosociology of Vascular Plants on an International Biosphere Reserve: Virgin Islands National Park, St. John, US Virgin Islands (Sonja N. Oswalt, Thomas J. Brandeis and Britta P. Dimick, extract from Caribbean Journal of Science, Vol. 42 No. 1, 2006)

Preliminary Report on the Architecture of Par Force Great House, Reef Bay, Virgin Islands National Park as Revealed by Archeological Testing (Roy W. Reaves III, 1988)

Proceedings of the Workshop on Biosphere Reserves and Other Protected Areas for Sustainable Development of Small Caribbean Islands, Caneel Bay, St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands, May 10-12, 1983 (Jim Wood, ed., 1984)

Proposed Establishment of Virgin Islands National Park (Elbert Cox, 1956)

Recreational Uses of Marine Resources in the Virgin Islands National Park and Biosphere Reserve: Trends and Consequences Biosphere Reserve Research Report No. 24 (Caroline S. Rogers, Larry McLain and Evonne S. Zullo, 1988)

Report on Archeological Investigations Conducted for the Installation of a Parking Lot at Great Maho Bay, Virgin Islands National Park (J. Lauran Riser, Ken S. Wild and Michal F. Wigal, 2009)

Report on Archeological Investigations at the Trunk Bay Sugar Factory, Virgin Islands National Park VIIS Accession Number 335 (J. Lauran Riser, Agnes Wraae, Marie Veisegaard and Ken Wild, 2011)

Research of the Barge Wreck in Careening Cove and it's role in 19th Century Charlotte Amalie Harbor Logistics (Casper Toftgaard Nielsen, 2009)

Resource Briefs (Coral Reef Monitoring in the Virgin Islands National Park): September 2013 • October 2017

Shallow-Water Benthic Habitats of St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands NOAA Technical Memorandum NOS NCCOS 96 (Adam G. Zitello, Laurie J. Bauer, Timothy A. Battista, Peter W. Mueller, Matthew S. Kendall and Mark E. Monaco, August 2009)

Terrestrial Invertebrate Animals of the Virgin Islands National Park, St. John, U.S.V.I: An Annotated Checklist (William B. Muchmore, October 1987)

The Danish Colonization of St. John, 1718-1733 (Lief Calundann Larsen, 1986)

The Historic Resources of the U.S. Virgin Islands: A Review and Assessment and Forms for Public Comment (The Cultural Resource Group, May 1988)

The Leinster Bay Estate (Nanna Wienecke and Louise Rasmussen, 2015)

The Pasquereau Estate, 1721-1848 (Anne-Kristine Sindvald Larsen and Charlie Emil Krautwald, December 2014)

Twenty years of forest monitoring in Cinnamon Bay Watershed, St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands (Peter L. Weaver, 2004)

Understanding the Petroglyphs, U.S. Virgin Islands (Ken Wild, 2004)

U.S. Virgin Islands: A Guide to National Parklands in the United States Virgin Islands NPS Handbook No. 157 (1999)

Virgin Islands Beach Processes Investigation, St. John, Virgin Islands Occasional Paper No. 1 (Scott Hoffman, Alan Robinson and Robert Dolan, February 1974)

Virgin Islands National Park (July 1955, reprinted November 1956)

Visitor Guide (Friends of Vigin Islands National Park, 2021)

viis/index.htm

Last Updated: 17-Mar-2025