|

A CONCISE HISTORY OF THE CIVIL WAR

"We divorced, because we have hated each other so." That is how Mary

Chesnut of South Carolina summed up what happened in America in the

early months of 1861. North and South, wedded by bonds of history,

blood, and sacrifice, simply could no longer make the marriage work. As

with any marriage, theirs contained the seeds of breakup from the very

outset, and as with any marriage, their life together had seen periods

of harmony and cooperation intermingled with stresses and discords

settled only by compromise, by each giving in a little to the other. But

by 1860-1861 the stresses were greater, the compromises fewer and less

effective, and finally what millions have known as "irreconcilable

differences" emerged on a national scale to drive the sections apart.

Only there was no judge to sit in deliberation on the dispute between

North and South or to impose a settlement. The struggle for their

divorce would have to be played out in a different sort of courtroom,

across ten thousand battlefields on the land itself. When the Founding

Fathers first agreed upon the Constitution, they little envisioned the

struggle for balance of power between the sections that the next century

would bring. Expansion and settlement of new territories to the west led

inevitably to new states joining the original thirteen. Gradually North

and South developed along different lines, dictated largely by geography

and immigration. In the states south of the Ohio River, soil and climate

lent themselves chiefly to large-scale agriculture and the planting of

cash crops, first tobacco and then cotton. Industry never saw much

expansion because there seemed to be little need for it, and the raw

materials proved less abundant than in the North. Instead, large stores

of cheap labor were needed to till and harvest the fields, a practice

for which slavery was ideal. Few cities emerged, and none of any size

other than New Orleans. Such as there were sprouted mainly on the

coastline as shipping ports to send the produce of Southern fields to

the North and Europe.

|

ILLUSTRATION FROM HARPER'S WEEKLY OF SLAVES

COVERING IN THE COTTON SEED. (LC)

|

By contrast, the soil of the North, plus its colder climate, favored

much more the small holding of the individual farmer rather than the

larger plantation-style agriculture. Instead, the abundant raw materials

in the earth encouraged a growth of industry. That, in turn, sparked the

growth of many and larger cities than in the South, and they soon

offered the lure of jobs and a new chance to untold thousands of

immigrants from Europe, which swelled the North's numbers even more.

Although slavery initially existed in the North, too, it quickly died

out, being both impractical for the needs of small farmers and growing

industry, as well as odious to the new immigrants and to their largely

strict Protestant fellow Northerners.

It required but a single generation after the Constitution's

ratification for the pressures of population and growth to lead to the

inevitable challenge to the balance of power. So long as the slave

states of the South stood evenly numbered with the nonslave states of

the North, political representation—and therefore power—in

Washington remained unthreatened. Each state was entitled to two members

in the Senate, and an even North-South split of the states ensured that

in the Senate, the interests of one section would not overpower those of

the other. By 1820 this became vitally important to Southerners, because

the growth of population, and its location, dictated that the House of

Representatives moved steadily toward a Northern majority thanks to the

influx of immigrants to the North. At least the Senate provided a check

on the House, and since by 1820 all but one of the presidents had come

from Virginia, the South stood in no fear of becoming a minority in

Washington.

|

(George Skoch)

|

But then Missouri applied for statehood. It would be the "odd" state,

if admitted with a prohibition of slavery, the so-called "free" states

would finally have a majority in the Senate as well. If Missouri was

admitted with slavery, the slave states would control the Senate. The

controversy quickly escalated into the first major crisis over

sectionalism faced by the young America. The Compromise of 1820, the

so-called Missouri Compromise, settled the issue, but that settlement

only postponed the controversy. It decreed that an artificial line be

drawn across the continent. All territories above that line would be

prohibited from embracing slavery when they became states, while all new

states from below the line could have it if they chose.

|

SENATOR JOHN C. CALHOUN OF SOUTH CAROLINA (LC)

|

For a time the compromise worked, but when war with Mexico came in

1846, Southerners quickly seized upon the opportunity to acquire huge

new tracts of Mexican land below the Missouri Compromise line that might

become new slave states. The North largely opposed the war, and for the

same reason, and the resulting agitation between the sections heated the

controversy even more. Meanwhile, already faced with minority status,

the South had seen the rise of a growing sentiment for an alternative to

majority rule. John C. Calhoun of South Carolina promoted a policy of

"concurrent majority" whereby any act of the national government would

not be binding on the minority states, unless a "majority" within those

states also concurred in the measure. Failing to do so, the minority

states could declare such acts null within their borders. This policy of

"nullification" became itself a major controversy, though the South

never attempted to put it into practice seriously. But the declared

alternative to nullification came more and more to be

discussed—secession.

Two years after the conclusion of the Mexican War, the crisis

escalated to a higher level in 1850, when California sought admission to

statehood. Hard and inventive work by Senator Stephen A. Douglas of

Illinois and Henry Clay of Kentucky crafted a patchwork compromise.

Their Omnibus Bill, which came to be called the Compromise of 1850,

admitted California as a free state and organized New Mexico and Utah as

territories without restrictions on slavery. The argument was put forth

that territories could decide the issue of slavery for themselves at the

time of their organization as territories. Southerners, notably Calhoun,

argued that this could prevent slaveholders from coming into a new

territory after its organization, virtually guaranteeing that when it

achieved statehood, its people would be overwhelmingly free staters and

opt to prohibit slavery. Only on applying for statehood itself, said

Calhoun, should the people of a territory be allowed to choose for or

against slavery. That way, Southern interests would have a chance to

expand, too. Very quickly the new lands to the west were becoming a tool

in the hands of those in the East, a lever that each side sought to use

to pry advantage to its side. The compromise also contained the Fugitive

Slave Law, which made it a crime for any Northerner to refuse to give

aid to those from the South seeking to recapture runaway slaves.

|

SENATOR STEPHEN A. DOUGLAS OF ILLINOIS (LC)

|

The outcry from both North and South after 1850 was more of outrage

over the losses incurred in the compromise than glee over gains.

Inevitably, the patchwork peace could not last, and in 1854 when talk of

Kansas coming into the Union emerged, the explosion erupted. The

Kansas-Nebraska bill abolished the Missouri Compromise line, outraging

the North, destroying the old Whig Party, and leading to the rise of a

new, entirely sectional Republican Party dedicated to containing slavery

where it existed. Moreover, it provided for "popular sovereignty," the

power of the inhabitants of a territory to decide the slavery issue for

themselves prior to statehood. The North felt outrage at what appeared a

massive giveaway to the slave interests. The South quickly sought to

capitalize on it, and soon, both pro- and antislave men flocked to

Kansas to try to constitute a majority. For the next four years Kansas

literally bled as they fought, connived, plotted, and plundered, in the

attempt to intimidate each other and dominate the slave issue. A

fanatical old man named John Brown soon emerged on the antislave side,

willing to murder any slaveholder indiscriminately. Soon the Southerners

reciprocated, and what could be called the first shots of civil war were

fired. The failure of a proslavery constitution in 1858 largely ended

the bloodshed, and a Supreme Court decision in the case of Dred Scott

that affirmed the unconstitutionality of the old Missouri Compromise

left slavery virtually intact in the Kansas territory and still

technically a possibility in all the remaining territories then

established or yet to be.

|

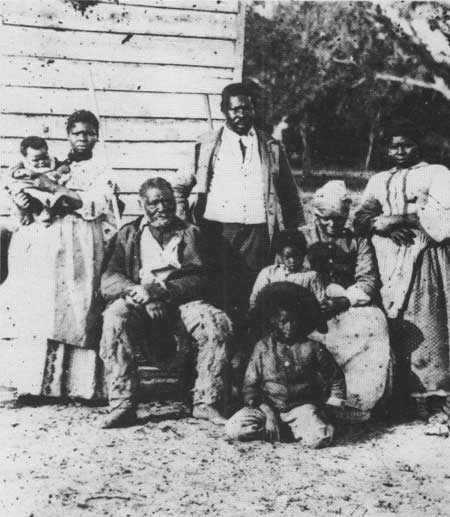

FIVE GENERATIONS OF A SLAVE FAMILY (LC)

|

|

JOHN BROWN (LC)

|

Through all of the controversy over the decades, a number of issues

arose to divide North and South. A protective tariff that favored

Northern interests rankled Southerners, and with justification: For

their part, Southerners came increasingly to suspect and then resent a

growing centralization of power in the Federal government, an

aggregation of power that seemed to them to reject the original notion

of their fathers in forming the Union as a "compact" of independent

states, banding together for mutual defense and benefit but yielding

none of their individual sovereignty.

These and other arguments flew back and forth, but in the end the one

overriding irreconcilable difference was slavery. Inevitably, when any

cry of "state's rights" was reduced to its bedrock, slavery lay there.

After decades of debate and argument, North and South each evolved

extreme positions that had as much to do with serving their political

interests as with any genuine feeling about the morality of slavery

itself. Virtually all people of the time regarded Negroes as inferior,

mentally unable to care for themselves or to function in a white

society. Even among the most prominent Northern abolitionists, dedicated

to abolishing slavery by law, there were few who believed in racial

equality. They simply did not like the idea of one man owning another.

Most anti-slavery people in the North would have shipped all the freed

slaves back to Africa, where the nation of Liberia had been formed many

years earlier expressly for that purpose.

Southerners were no more racist than Northerners. Believing in black

inferiority, they looked on slavery as a benevolent institution that

provided food, clothing, and shelter for their slaves, in return for

their labor. It was, they argued, the only way the two races could live

in the same country together. Southerners, in fact, felt a mortal fear

of what would happen if the slaves in their midst should be freed. By

1860 there were 9 million Southern whites and more than 4 million

slaves. Freed, without property, money, education, or trades, the blacks

might become a dread danger to the fabric of Southern economy and

society. And of course, they were the labor upon which Southern economy

was founded. Planters had an enormous capital investment in slavery.

Abolition could ruin them. By 1860 slavery was not an institution that

the Southerners of the time had created. Many even felt uncomfortable

with it, for moral, religious, and other reasons. But it was an

institution that they were stuck with. And for both North and South, it

had become the single issue over which power in America was to be

defined, and with it the future of the Union.

|

THE

U.S. MARINES. LED BY COLONEL ROBERT E. LEE, STORM THE ENGINE HOUSE

CONTAINING BROWN'S MEN. (LC)

|

Matters came to a head with alarming speed. In October 1859 old John

Brown, now at the head of a tiny "army" of fellow fanatics dedicated to

overthrowing slavery by violent means, led an early morning raid on the

United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. He hoped to seize the

arms and use them to equip thousands of slaves whom he expected to rally

to him. Instead, he bungled the raid, was trapped and besieged, and

finally captured. Two months later he and his companions were hanged. A

failure in life, John Brown became, in death, a martyr for the abolition

cause and a lightning bolt to electrify Southern fears of a conspiracy

to overturn slavery. The next year, when Abraham Lincoln won the

presidency at the head of the Republican Party, Southerners believed

their worst fears had been realized. From their point of view, there was

no alternative but secession from the Union if they were to protect

their institutions from Northern assault.

Each state's action was entirely

separate; they did not leave the Union in a group, nor did they

coordinate their movements.

|

South Carolina went first in December, to be followed shortly by

Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia, Florida, Louisiana, and Texas. Each

state's action was entirely separate; they did not leave the Union in a

group, nor did they coordinate their movements. And they did not leave

one nation with the specific intent of creating another. Nevertheless,

it became evident quickly that their strength lay in banding together.

On February 4, 1861, delegates from the states then seceded met at

Montgomery, Alabama, and created a new government, the Confederate

States of America. In a remarkably short time they drafted a

constitution, elected Jefferson Davis their president, and set up the

basis of a working government.

A brilliant martial enthusiasm seized the South at the same time.

Volunteers poured out of every city and state, flocking to Montgomery,

seizing United States property in their states, or gathering at

Pensacola, Florida, and Charleston, South Carolina, where Federal

garrisons still refused to give up Forts Pickens and Sumter. Within

barely more than two months, the Confederates had more than 20,000 men

under arms, actually outnumbering the United States Army, which at the

time had barely over 13,000 soldiers, most of them scattered around

frontier posts in the West.

|

VIEW OF MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA, CIRCA 1861. (LC)

|

Thus, when Lincoln took office on March 4, he faced a terrible

dilemma. His oath of office obliged him to hold and occupy all Federal

property, and his concept of the Constitution and of the Union as being

perpetual required that he view the Confederates not as a separate

people but as Americans in rebellion. Yet he, like they, did not want to

come to blows. Unfortunately, conflict seemed inevitable. Confederate

emissaries came to Washington to attempt to negotiate a peaceful

settlement of differences, seeking to get the Union troops out of Forts

Sumter and Pickens, and prepared to discuss compensating the Union for

Federal property seized in the South. But Lincoln could not meet with

them without constituting a form of recognition of their independence,

which he denied. Nor could he abandon the forts without betraying his

oath and crippling his administration at its outset.

As a result, while intermediaries unofficially tried to put off the

Southern commissioners in the hope that the passage of time would dampen

their enthusiasm, Lincoln and General-in-Chief Winfield Scott and Navy

Secretary Gideon Welles planned to resupply the starving garrison of

only 79 men in Fort Sumter. But then, just as the relief expedition was

ready to sail for Charleston, the Confederate emissaries decided that

their mission was futile and notified Montgomery. At once President

Davis telegraphed to his general commanding Confederate forces in

Charleston, Pierre G. T. Beauregard, to demand the surrender of Fort

Sumter on threat of bombardment.

|

SECRETARY OF THE NAVY GIDEON WELLES (USAMHI)

|

Fort Sumter was a massive masonry edifice on an island of rubble in

the middle of Charleston Harbor. Still unfinished, it mounted only a few

of the heavy guns it was designed to hold, and the tiny garrison,

commanded by Major Robert Anderson, was hardly large enough to work even

the few cannon in place. A Southerner himself, Anderson felt some

sympathy with the Confederates, but his uniform and flag meant more to

him, and he resolutely stood by his orders to hold the fort. Only his

dwindling rations might force him out. Hoping to avoid bloodshed, he

told Beauregard that he could not hold out beyond April 15, at which

time, his supplies exhausted, he would have to evacuate. Beauregard was

willing to wait, but when word came that the relief expedition was on

its way, he realized that Anderson might hold out indefinitely if

resupplied. Consequently, late on the night of April 11-12 Beauregard

demanded Anderson's surrender. If he refused, the Confederate batteries

on the shore ringing Sumter would open fire at 4:30 A.M., April 12.

Anderson had no choice but to refuse.

|

ATTACK ON FORT SUMTER, APRIL 12, 1861, SIGNALING THE START OF THE CIVIL

WAR. (LC)

|

The bombardment commenced with the skies still dark, the shells

tracing blazing paths across the skies over the harbor. All of

Charleston turned out to watch the event. At first Anderson did not fire

back, having little ammunition, few working guns, and no desire to

expose his men to harm. But in time he began to return a sporadic fire,

and the Confederates actually cheered when he did. They did not want a

victory in which the foe refused to fight back. All through that day and

the night following the bombardment continued. By the morning of April

13 wooden barracks inside Fort Sumter had been set afire, Anderson's men

could not fight the fire without exposing themselves to the shells

exploding in their parade ground, and the flames were creeping closer

and closer to the powder magazine. At 1:30 in the afternoon Anderson

signaled that he would give up. The next day, allowed to carry out his

arms and to fire a salute to his flag, Anderson and his unhurt garrison

marched out of Fort Sumter and boarded a ship to take them north. Such

as it was, the Confederates had a victory.

|

GENERAL PIERRE G. T. BEAUREGARD (CWL)

|

|

MAJOR ROBERT ANDERSON (CWL)

|

North and South were stunned by the events in Charleston Harbor.

Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion,

proclaimed a blockade of Southern ports, and began making plans first to

protect Washington and then to invade the South. In Montgomery, Davis

and his government redoubled their own efforts, calling for up to

100,000 more volunteers. Great news came just days after Sumter's fall

when Virginia seceded. Like other states on the border between North and

South, the Old Dominion had ties to both sections and remained neutral

at first. But when the firing broke out and Lincoln made it clear that

he would attempt to coerce the South back into the Union by force, most

of the border states took sides. Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina

followed Virginia into the Confederacy, while Missouri, Kentucky, and

Maryland wavered but eventually remained in the Union.

With Virginia's secession it became evident that it would be the

first target of the army Lincoln was building in Washington. Deciding

that Montgomery was too remote, the Confederate Congress voted to move

the capital to Richmond, and in the last week of May Davis and his

cabinet made the move, followed by the rest of the government. Already

Davis had been concentrating new volunteer regiments in northern

Virginia near Manassas on what would have to be the main route of any

Yankee advance toward Richmond. He assigned the South's new hero

Beauregard to command there, while building a smaller army led by

General Joseph E. Johnston 100 miles to the west in the Shenandoah

Valley. In case of advance against either army, the Confederates could

use a railroad between them to travel to each other's aid.

They did not have to wait long. Lincoln and Scott built an army

mostly of volunteers numbering over 30,000 in and around Washington. A

former major, Irvin McDowell, now commanded it as a brigadier general in

spite of never having led troops in battle before. It was to be a time

of amateurs, North and South, for no one had experience with armies of

the size the Civil War would see, and those officers who had seen action

in the Mexican War had rarely led more than a company of soldiers.

Everyone had to learn on the job now, and those who learned the fastest

would be the first to succeed.

|

|