|

|

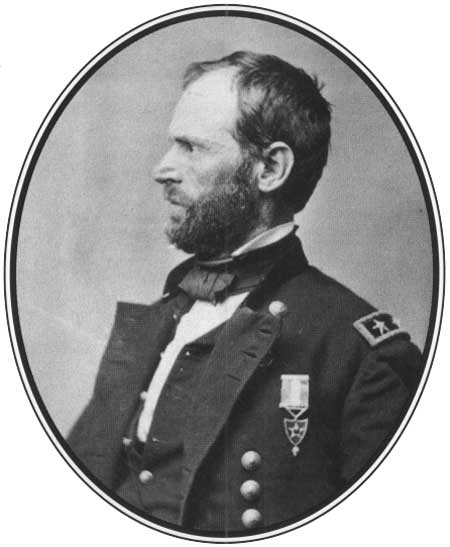

IN DURANCE VILE

by William Marvel

In the years following the war, former prisoners from both sides

wrote voluminously about their experiences in captivity. Almost without

exception they exaggerated their suffering, though there was really no

need for such amplification, and most of them tried to implicate their

captors in schemes of deliberate attrition. North and South, though, the

majority of prison-keepers attempted to meet their obligations.

Early in the conflict, when many hoped for a short war, prisoners

could look forward to long incarcerations. Men captured at First Bull

Run were sent to warehouses and forts from Richmond to Charleston, and

some were transferred to the Deep South, where they spent as long as a

year awaiting release. As the war dragged on, however, authorities

sought a means of repatriating prisoners on a regular basis. Opposing

officers negotiated various proposals, but not until July 22, 1862, did

the two sides agree on a formula for prisoner exchange.

The Dix-Hill cartel, named for the Union and Confederate generals who

devised it, required that, within ten days after they were captured, all

prisoners would be paroled—that is, they would take an oath not to

fight again until they had been exchanged for an enemy soldier of equal

rank. The captors would then transport the prisoner to an agreed-upon

point of exchange and release him to his own officers. Sometimes the

exchange was made right at the steamboat landing where the prisoner was

delivered; if one side turned over more men than the other, the

unexchanged prisoners went free anyway, though they were still bound not

to fight until their government had exchanged an equivalent enemy

soldier.

This arrangement continued in force for about a year without serious

interruption. Whole regiments, divisions, and even armies were released

under its provisions, including the Federal garrison at Harpers Ferry

and the Confederate army captured at Vicksburg. Confederate and Union

exchange agents began to dispute their tallies in the summer of 1863,

particularly when Confederates announced the questionable exchange of

troops captured at Vicksburg, but late that year an even greater

impediment arose in the form of black Union soldiers. Confederates had

threatened to try U.S. Colored Troops and their officers for inciting a

slave revolt, which meant the noose, and they steadfastly refused to

exchange black prisoners suspected of having fled from bondage. That

proved unacceptable to the North, and by the end of 1863 prisoner

exchanges had all but ceased.

Prison populations grew quickly from there, particularly after the

campaigns of 1864 began. In January of that year Confederates began

building an open stockade pen in Sumter County, Georgia, that came to be

known as Andersonville and four months later Northern carpenters began

raising a board fence around some empty barracks at Elmira, New York.

Existing prisons from Chesapeake Bay to Texas began to swell with

inmates, and as the months passed the health of those prisoners grew

progressively worse.

Andersonville was the worst, by far. By August of 1864, 33,000

undernourished Yankee prisoners lay within its twenty-seven acres, and

before the war ended over 41,000 had been confined there at one time or

another: just under 13,000 of them lie buried in the prison cemetery,

and hundreds more died before they reached home. Nearly a quarter of the

12,000 Confederates held at Elmira also perished.

In the cold, damp climate of the North, respiratory ailments carried

away the greatest number of prisoners. In the South, dietary

deficiencies and dysentery accounted for the worst mortality. Perishable

produce could not be obtained in sufficient quantities to accommodate

imprisoned Federals, especially the masses at Andersonville, and scurvy

probably caused or contributed to more deaths than any other single

factor. The postwar complaints of former Union prisoners

notwithstanding, their prison rations did not fall so short in quantity

as they did in quality and variety. Scurvy also affected Confederate

soldiers, both those in the field and those in Union prisons.

Confederate authorities faced depleted provisions and an abysmal

transportation system in their quest feed not only their own troops but

their unwilling guests.

Confederate authorities faced depleted provisions and an abysmal

transportation system in their quest to feed not only their own troops

but their unwilling guests. Ironically, it was the better-supplied

government of the United States that deliberately withheld food from its

prisoners: after listening to bitter tales brought back by Union

soldiers who had escaped from places like Andersonville, Lincoln's

secretary of war ordered rations in Northern prisons reduced in

retaliation.

With the end of the war in sight, the Federal government agreed to

resume general exchanges in the first weeks of 1865. By spring the

trains and steamships had begun returning thousands of frail, filthy

survivors to receiving stations where attendants shook their heads in

pity. The last of nearly half a million wartime prisoners had come home

by the end of June, but decades of recriminations had only begun.

|

|

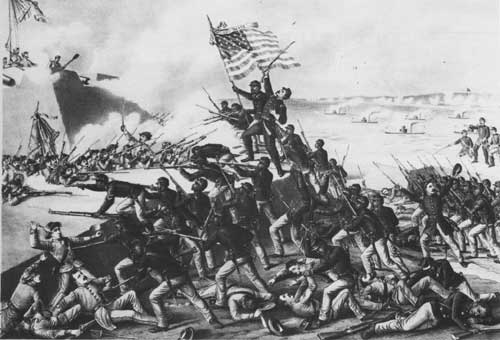

STORMING FORT WAGNER, CHARGE OF THE 54TH MASSACHUSETTS. (LC)

|

While the conflict chiefly offered the men in blue and gray an

opportunity to lose their lives in a host of ways, or else to spend the

rest of life as invalids, the war did actually broaden the horizons of

opportunity for others. Most notable, of course, were the several

million blacks in America, free and slave. A successful maintenance of

the Union meant for all slaves, after the war's end, freedom at last.

But for the blacks of the North, it meant something more immediate even

while the war raged. Almost from the outset abolitionists and others

raised a cry that black men should be allowed to become soldiers in

order that they, too, could fight for the Union. After the Emancipation

Proclamation, the cry became even more to the point when now these men

would also be fighting for the freedom of their brothers in bonds.

And blacks wanted to fight. It would be the first time they would be

recognized as almost the equals of whites, for even if they remained at

the bottom of the class ladder in civilian life, a soldier on the

battlefield carried the same weapon, wore the same uniform, fought under

the same flag, and shared the same risks, white or black. Although

efforts to enlist them began as early as 1861, Lincoln prudently waited

until after the Proclamation for fear that putting blacks in uniform

would stampede the slave states like Kentucky and Missouri that still

remained in the Union. In September 1862, however, the first tentative

recruiting began, and blacks showed themselves eager to enlist. By the

end of the war more than 175,000 wore the Union blue, and that did not

include thousands more who served as civilian teamsters, cooks, and

laborers. They formed at least 166 regiments of what were designated

United States Colored Troops, as well as in some of the state services,

and when they got the opportunity to go into battle, they acquitted

themselves as soldiers. In spite of an early reluctance to use them in

battle, their commanders found them reliable and valorous, especially

when they went into action knowing that Confederates had vowed no

quarter for captured ex-slaves. In fact, in a few engagements, chiefly

at Fort Pillow, Tennessee, and Saltville, Virginia, both in 1864,

Confederates did shoot down wounded and surrendered blacks after the

fighting had ceased, but especially at the latter the Richmond

government did not countenance such actions and instituted its own

investigation to punish perpetrators. Before the war's end, blacks won

the coveted Medal of Honor and saw the first of their number rise to

officer rank. Even the Confederacy considered enlisting blacks early in

the war, but of course could not without undermining its own foundation

on the inequality of the races. But by 1865 Davis and the Congress,

desperate for manpower, authorized the raising of black troops from

among slaves volunteered by their masters, with the conditional promise

of emancipation for their services after the war. In the end, of course,

all Confederate blacks got their freedom.

Women, too, came into a bit more of their own during the conflict. In

fact, some wanted as much as their husbands and brothers to share in the

excitement. Perhaps as many as 400 of them posed as men to enlist and

fight in the armies. Some did so to be close to their husbands. Others

simply sought adventure, and a few kept up the masquerade even after the

war ended. Jenny Hodgers served throughout the war as Private Albert

Cashier with no one ever suspecting her secret until decades later.

|

CLARA BARTON (NA)

|

Such women were the exception, of course. Tens of thousands

contributed in other ways. Most worked as volunteer nurses in the

hospitals, and in the Confederacy some were actually given military

rank. Others organized and ran soldiers' relief organizations. Clara

Barton established the forerunner of the Red Cross in her efforts to aid

the sick and wounded, while in Richmond Phoebe Pember acted as chief

matron of the massive Chimborazo Hospital, the largest of the war. And

with so many of the men gone to war, and especially in the Confederacy,

the women left behind ran the farms and managed the small businesses and

took over the schoolrooms abandoned by their husbands. Women ran

newspapers and factories, acted as spies and scouts, and performed every

other task that the men would allow—or that they could take on

themselves. Never before in American society had women so boldly stepped

out from behind their aprons to participate in the life of the

nation.

|

WOMEN WORKERS FILLING CARTRIDGES AT A FEDERAL ARSENAL. (LC)

|

The war also saw the involvement of a number of others on the fringes

of traditional white American society. Indians fought on both sides in

the war, chiefly in the Trans-Mississippi. For some it was merely a

continuation of old intertribal rivalries, but others sensed that in

helping the white man they might help their own lot. Most were doomed to

disappointment, of course, yet one of them, the Cherokee Stand Watie,

rose to become a brigadier general in the Confederate army, while Ely S.

Parker, a Seneca, became Grant's military secretary and gained a

brevet—or honorary—promotion to brigadier. Mexican-Americans

also served in a few units from Texas for the Confederates, and Colorado

for the Yankees, again chiefly in the Trans-Mississippi. Huge numbers of

Irish immigrants went into the Northern armies, constituting whole

regiments like the famous "Fighting 69th" New York. Germans from the

several Prussian states also gave their unwavering support to the Union,

especially when urged on by men like Sigel. In all, half a million

foreign-born men enlisted to constitute more than a fourth of the Union

army, leading Confederates derisively to call them mercenaries. In fact,

having fled the Old World with its chaos and autocracy, they embraced

wholeheartedly the ideals of the Union and fought for it

unreservedly.

Indeed, both sides fought without reservation, which is why the war

proved so costly. By the spring of 1865, after almost four years of it,

Americans North and South were exhausted, continuing the fight out of

grim determination. Inevitably it had to end, and perhaps it was

inevitable that it end as it did. Grant, who had been a Confederate

nemesis since Fort Donelson, precipitated the final collapse. He

continued his gradual encirclement of the Richmond and Petersburg

defenses until April 1, when at last he stood within striking distance

of the last railroad leading out of the Confederate capital. Lee and

Davis had no choice but to move their army and evacuate the city the

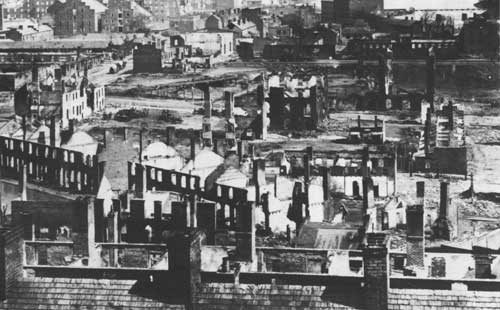

next day, or else be completely surrounded and cut off. On April 2 the

government burned what records and supplies it could not take with it

and began the sad march west.

|

RICHMOND, THE FORMER CAPITAL OF THE CONFEDERACY, LIES IN RUINS. (LC)

|

Lee's retreat was a daily tale of sorrow. Dogged at every step by

Grant, and especially by his relentless cavalry under Sheridan, the

Confederates staggered onward. On April 6, as they lay stretched out for

miles along the road, the column became badly divided and the Yankees

swooped in upon them. More than 8,000 Rebels fell captive, leaving Lee

with fewer than 30,000 soldiers. The next day Lee fought them at

Farmville and delayed Grant's pursuit for several hours. He crossed the

Appomattox River and pressed onward, hoping somehow to reach North

Carolina to join with the other Confederate army there. Unfortunately,

while he fought at Farmville, Lee gave Sheridan time to move on south

and west, poised to cut off his line of march. This same day Grant sent

Lee a message suggesting that now was the time to surrender. Lee

responded saying not yet, not yet, but he did ask what Grant's terms

would be.

|

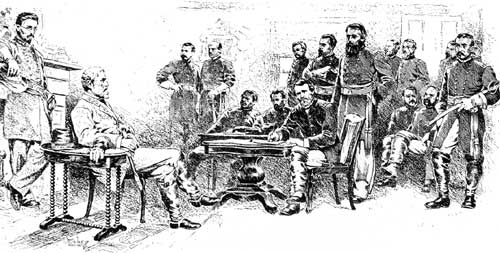

THE SURRENDER SCENE AT APPOMATTOX AS SKETCHED BY WALTON TABOR. (BL)

|

The next day it happened. Sheridan's cavalry got ahead of Lee and

captured vital supplies that were awaiting him at Appomattox Station.

Infantry soon joined him, and by that evening, when Lee was near

Appomattox Court House, he learned that he had nowhere to go unless he

could attack Sheridan and push him aside. His senior commanders

suggested that it was time to surrender. Grant sent another note

offering the most generous of terms. Still Lee said not yet. The great

fighter could not yield until he felt convinced that he could fight no

more.

The next morning he launched an attack that startled but could not

budge the Yankees. Now at last Lee knew that he had fought his last.

Further fighting would be murder. He sent a message to Grant asking for

a meeting. Soon thereafter they both rode into Appomattox Court House, a

small village between the armies, to the home of Wilmer McLean.

Ironically, McLean's earlier home on Bull Run had been Beauregard's

headquarters during the first battle of the war, and now one of its last

acts was to take place in his parlor. The two commanding generals were

uncomfortable at first, Lee feeling humiliation in defeat and Grant

overwhelmed with sympathy for a gallant foe. They made brief small talk

of earlier days, and then Grant made good on his promised generosity.

Lee's army must surrender only its arms and give its parole to go home

and fight no more. He even allowed any Confederate claiming to own one

of its army's horses to take it with him, to use in his spring planting

when he got home. And Grant opened his commissaries to the hungry

Confederates. Lee accepted, and it was over. Within hours old friends in

blue and gray began to mingle in each other's camps to renew

acquaintances and bind their emotional wounds. Three days later the

formal surrender ceremony took place, and the Army of Northern Virginia

passed into history.

|

THE MCLEAN HOUSE SHORTLY AFTER THE WAR. (LC)

|

But the war was not over. President Davis and his cabinet had moved

to Danville, Virginia, but on learning of Lee's surrender, they had to

continue their flight south into North Carolina. The only other

remaining army in the East was there, a remnant of the once mighty Army

of Tennessee combined with other commands, and since February once more

commanded by Davis's old foe Joseph E. Johnston. Only Lee's specific

request persuaded the president to give the post to Johnston once more.

Meanwhile, on February 1 Sherman had begun his drive north from

Savannah. He moved behind Charleston, cutting it off and virtually

forcing its surrender without a fight, and moved on toward the South

Carolina capital at Columbia. Some 60,000 men marched with Sherman, and

facing them were only scratch forces totaling less than 25,000, though

more small commands joined the Confederates throughout the following

campaign.

As soon as he took command, Johnston concentrated all of these

scattered commands in the vicinity of Fayetteville, North Carolina,

knowing that his only hope of stopping Sherman was to use every man at

his disposal. But Johnston had to withdraw before he could accomplish

his objective and continued to retreat through North Carolina until he

turned and struck at Sherman at Averasborough on March 16. Still he had

to retreat once more, but three days later he turned at Bentonville and,

in an unusual act for Johnston, launched a concerted attack that

achieved some success until the weight of the Yankee numbers forced him

to withdraw. Johnston would not fight again. He took position not far

from the capital at Raleigh, where he hoped Lee would be able to join

him. But when he learned of Lee's surrender, he believed that his own

must follow. By April 12 Davis and his cabinet were in Greensborough,

and there Johnston told them he thought it was useless to continue.

Davis disagreed but allowed Johnston to meet with Sherman to discuss a

temporary armistice. Instead, five days later Johnston and Sherman

reached an agreement calling for the disbanding of all remaining

Confederate forces in the field, something Johnston had not the power to

order. A week later Washington rejected the terms because Sherman did

not have the authority to make such an agreement either. Johnston then

immediately surrendered his own army without seeking Davis's permission.

The war in the East was over.

|

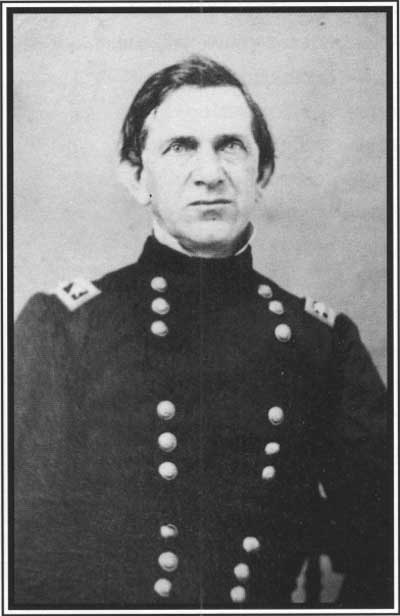

MAJOR GENERAL EDWARD CANBY (CWL)

|

|

MAJOR GENERAL WILLIAM T. SHERMAN (CWL)

|

It remained now to stop resistance in the West. On May 4 the last

remaining Rebel army east of the Mississippi surrendered to General E.

R. S. Canby at Citronelle, Alabama. Three weeks later Kirby Smith's

representatives met with Canby's officers in New Orleans and agreed on

the surrender of the Trans-Mississippi army. Now all of the armies had

laid down their arms, with only a few scattered Confederate commands

still either holding out or else simply going home without formal

surrender. A month later, on June 23, in faraway Doaksville in the

Indian Territory, Stand Watie made the last formal surrender of a

Confederate military command. It was all over, all, that is, except for

one ship. The CSS Shenandoah, a commerce raider plying the

Pacific, did not get word of the surrenders until August 2 and meanwhile

kept taking Yankee prizes. She finally steamed halfway around the world,

at last turning herself over to British authorities in Liverpool,

England, on November 6, seven months after Lee's surrender. The last

guns, at last, had been fired.

Even as the surrenders were taking place, one shot rang out that

would be heard throughout the ages. On April 14, flush with victory,

President Lincoln fell to an assassin's bullet at Ford's Theater in

Washington. The shock of the act stunned even the South. The Union went

into deep and lasting mourning. Confederates, who had nothing to do with

the lone act of the assassin, realized that Lincoln had been their best

hope for reconciliation without reprisal. Andrew Johnson succeeded

Lincoln in the White House and bravely tried to carry out Lincoln's

moderate policy, but he would come increasingly into conflict with the

radical element in the Republican Party who wanted to impose a more

punitive reconstruction on the South. The seeds for the acrimony and

excesses on both sides that would follow during the era of

Reconstruction had been sown.

Many blamed Davis, who had no knowledge of the assassination plot and

would not have countenanced it. After Johnston's surrender, he and his

cabinet continued their flight, but one by one his advisers left him,

and by early May he was almost on his own with a small escort. He still

hoped to reach the Trans-Mississippi, there to continue the fight, but

on May 10, near Irwinville, Georgia, Yankee cavalry finally caught up

with him. He would be sent to Fort Monroe and kept there as a prisoner

for two years before the government finally decided not to prosecute him

for treason.

|

EXECUTION OF MAJOR HENRY WIRZ. (USAMHI)

|

|

THE ASSASSINATION OF PRESIDENT LINCOLN AT FORD'S THEATRE ON THE NIGHT OF

APRIL 14, 1865. ILLUSTRATION FROM HARPER'S WEEKLY. (LC)

|

Indeed, despite all the anger and hatred generated by the war, the

Union authorities showed incredible magnanimity. No one was tried for

treason. Davis and a few others were imprisoned for a time, but by 1867

all were released, and many eventually recovered their citizenship and

even held public office once more. Only one Confederate lost his life to

justice after the war, and that was Henry Wirz, commandant of the prison

camp at Andersonville. Even he probably did not deserve his fate, but

the emotionalism over Andersonville was so great that someone had to

pay, and the unlucky Wirz was the most visible object. Nevertheless,

after four years of war, after the loss of more than 600,000 lives, with

hundreds of thousands of others carrying the mental and physical scars

of their war, the empty sleeves and the broken lives, the speed with

which North embraced the South once more, and with which the veterans

tried to put their war behind them, stands perhaps unique in the annals

of history.

|

PARADE IN WASHINGTON, DC CELEBRATING THE END OF THE WAR. (LC)

|

|

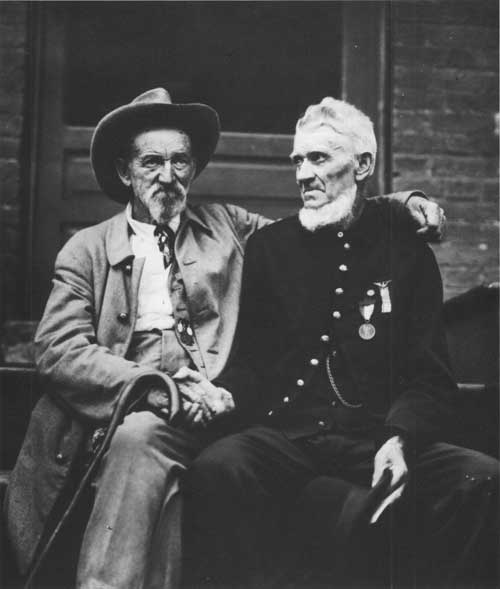

CONFEDERATE AND UNION CIVIL WAR VETERANS AT THE 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE

BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG. (LC)

|

And as they went back to their fields, their schoolrooms, and their

clerks' desks, the men of North and South pondered what it had all been

about and what they had accomplished. Two questions they settled

irrevocably for all time. Slavery was at an end in America. The blacks

may have gotten nothing else from the war, but they got their freedom.

That counted for a lot, but it was all they got, and even as the day of

trial for whites came to an end, the century of black struggle was just

beginning. And the war also settled once and for all that the Union was

greater than its component parts, that it was eternal and indivisible.

Never again would state or section countenance or even talk of

secession.

Win or lose, living and dead, soldier and civilian, they had

participated in something that set America apart, that renewed a nation

and set it on the path to world power.

|

Yet other questions remained. It all came at such a terrible price.

Would not slavery have come to a natural end in a few more decades

anyway, as the scorn of the rest of the Western world made it an

increasing embarrassment to the South? Would not the inevitable coming

of industrialization and mechanization have rendered slave labor too

expensive and therefore encouraged voluntary emancipation? And if

Southerners manumitted their slaves on their own at some future day,

what other issue could ever arise that could foment the kind of rancor

and division that led them to try to break away in 1861? No one could

know the answers. All they knew, North and South, were the answers the

war gave them, and each man had to decide for himself if the result

justified the sacrifice. Yet on one thing they could all unite. Win or

lose, living and dead, soldier and civilian, they had participated in

something that set America apart, that renewed a nation and set it on

the path to world power. In the process, they had spent their blood and

their youth and experienced the greatest adventure of their generation

and left their mark upon the defining moment of their century.

|

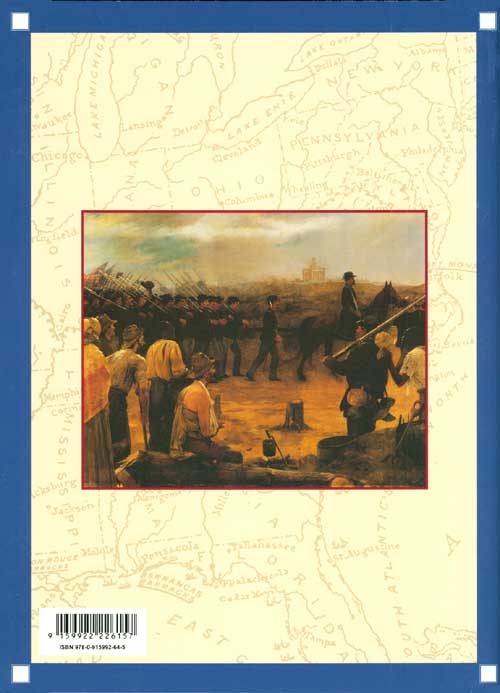

Back cover: "Fourth Minnesota Regiment Entering Vicksburg,"

painting by Frances Millet, courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society.

|

|

|