|

|

THE FIELD GENERALS

by William Marvel

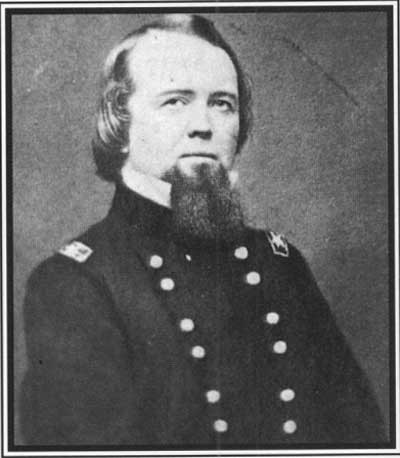

UNION

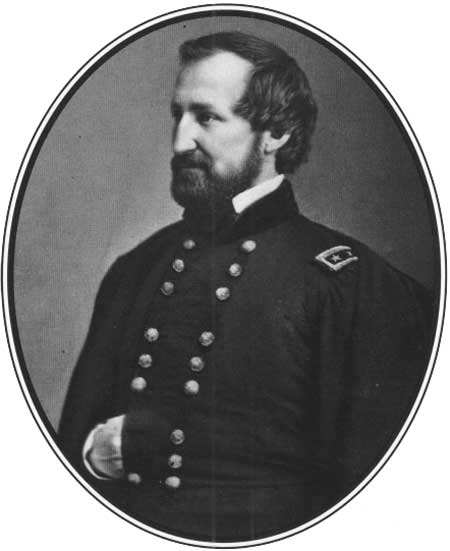

GEORGE BRINTON MCCLELLAN, 1826-1885. A top West Point graduate and a

promising staff officer before the war, McClellan had spent a few years

as a railroad executive before winning prominence in an early campaign

in western Virginia. This led President Lincoln to appoint him commander

of the army that had been defeated at First Bull Run, and later he put

McClellan in charge of all Union forces.

McClellan moved his army slowly up the York River peninsula toward

Richmond after much prodding from the government, but he was sent

reeling back to the James River in a week of almost continuous fighting.

Afterward he stopped the Confederate invasion of Maryland, but failed to

demolish the much smaller Southern army at the battle of Antietam.

A brilliant administrator, he instilled in the Army of the Potomac an

esprit de corps that survived his battlefield defeats. McClellan proved

insufficiently bold before the enemy, moving slowly and failing to

strike aggressively when the occasion called for it, For that Lincoln

removed him after the battle of Antietam. McClellan also harbored

political objectives hostile to those of the Lincoln administration, and

in the 1864 election he stood unsuccessfully as the Democratic candidate

for president.

GEORGE GORDON MEADE, 1815-1872. Born in Cadiz, Spain, where his

father was a diplomat, Meade entered West Point at the age of sixteen

and graduated in 1835. A year later he resigned to become an engineer,

but he was reappointed in 1842 and served in the Mexican War. He

remained in the army as an engineer until the outbreak of the Civil War,

when he was given his first field command as a brigadier general of

volunteer infantry. Wounded during the Seven Days in 1862, he led a

division at Antietam and rose to corps command after Fredericksburg.

Two days before the battle of Gettysburg Meade was assigned to

command the Army of the Potomac, which he led ably enough through that

battle, but he was criticized for his failure to capture the entire

Confederate army. He continued in command until the end of the war, but

from the spring of 1864 he was reduced to little more than a figurehead

because the general-in-chief, Grant, traveled with that army. A gruff,

disagreeable man with a violent temper, Meade argued with nearly all his

chief subordinates at one time or another.

ULYSSES SIMPSON GRANT 1822-1885. Grant enjoyed the greatest success

story of the entire Civil War. After graduating in the bottom half of

the West Point class of 1843, he served under both Zachary Taylor and

Winfield Scott during the Mexican War, but the peacetime army left him

lonely and bored. He turned to the bottle for solace and finally

resigned as a captain in 1854. He failed even more miserably in civilian

life and was virtually subsisting on the charity of his family when the

Civil War erupted.

Again showing the stubborn determination that served him so well,

he hammered the enemy mercilessly, launching coordinated offensives in

all theaters of the war.

|

First given command of an Illinois regiment, Grant was soon appointed

brigadier general. He achieved some notoriety with an attack on Belmont,

Missouri, in November of 1861, but real fame came the next February,

when he captured an entire Confederate army at Fort Donelson, Tennessee.

His failure to take adequate precautions at Shiloh led to a surprise

attack that nearly drove his army into the Tennessee River, but his

stubbornness saved the day and reversed the tide of battle.

With the capture of Vicksburg Grant gained command of all Union

forces in the western theater, and his spectacular victory at

Chattanooga led Congress to approve his appointment as lieutenant

general and general-in-chief of all Federal armies. Again showing the

stubborn determination that served him so well, he hammered the enemy

mercilessly, launching coordinated offensives in all theaters of the

war. Lee's surrender at Appomattox was the acme of Grant's career, which

was later tarnished by an embarrassing foray into politics, where his

simple principles of courage and determination proved ineffective

against special interests and greed.

WILLIAM TECUMSEH SHERMAN, 1820-1891. Sherman graduated near the top

of the class of 1840 at West Point. He spent the Mexican War in

California, where there was little armed conflict, and he resigned in

1853 to become a banker there. In 1857 he returned to Ohio and gained

admission to the bar, but that career displeased him and he sought

reappointment in the army. Instead he found employment at a military

school in Louisiana, resigning as superintendent two years later, when

war broke out.

Given a Regular Army commission as colonel, Sherman led a brigade at

First Bull Run, then took command of Union forces in Kentucky as a

brigadier general. There he ran afoul of hostile newspapers that throve

on his controversial remarks about the conduct of the war, and he

hovered on the brink of a nervous breakdown when he was relieved. His

career was saved by assignment to the army of Ulysses Grant: the two

worked together successfully for the next two years, and when Grant took

the top command he left Sherman in charge in the West.

Sherman waged war on all fronts, striking not only at the South's

armies but at its economy and its will to resist.

|

Sherman waged war on all fronts, striking not only at the South's

armies but at its economy and its will to resist, and his devastating

March to the Sea marked the advent of modern warfare. He proved as

magnanimous in peace as he had been relentless in war, however, and the

surrender terms he first offered to Joseph Johnston's Confederate army

were so generous that the government refused to honor them.

PHILIP HENRY SHERIDAN, 1831(?)-1888. Appointed to West Point in 1848,

Sheridan was dismissed for attacking a cadet sergeant, but he was

reappointed and graduated well down on the list in 1853. He served

inconspicuously in the peacetime army and was still a lieutenant when

the war began. For another year he remained at company rank, performing

quartermaster service in the western theater, but in May of 1862 he was

finally given command of an infantry regiment.

From there Sheridan rose meteorically to command of a brigade,

earning a general's star in July and taking command of a division in

September. He fought well at Perryville, Stones River, and Chickamauga.

Grant noticed his performance at Chattanooga, where Sheridan's division

stormed Missionary Ridge and chased the enemy into Georgia, and the

following spring Grant chose the diminutive Irishman to command the

cavalry of the Army of the Potomac.

Sheridan's troops killed General J. F. B. Stuart in their first raid

that year, and in August he was given command of the Union army in the

Shenandoah Valley. There he trounced a smaller Confederate army at

Winchester and Cedar Creek, and early in 1865 he scattered the remnants

of that force at Waynesboro. Grant gave Sheridan effective command of a

large portion of the Army of the Potomac at Five Forks, and Sheridan led

one wing of the pursuit to Appomattox. A feisty, egotistical, and

ambitious little fellow, once Sheridan tasted success he seemed

unwilling to let anything stand in his way.

|

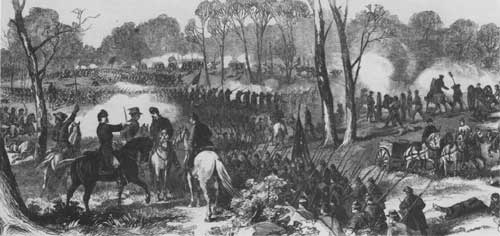

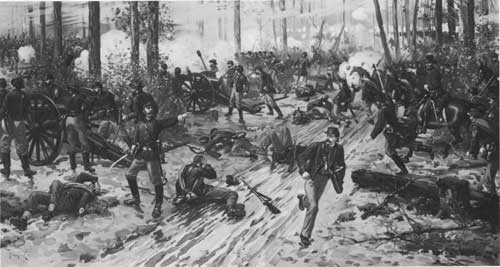

THE BATTLE OF PEA RIDGE (LC)

|

CONFEDERATE

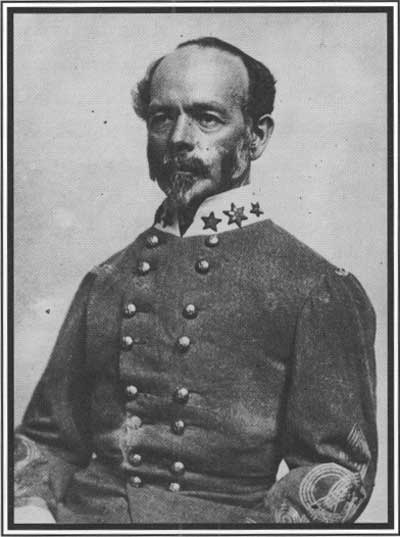

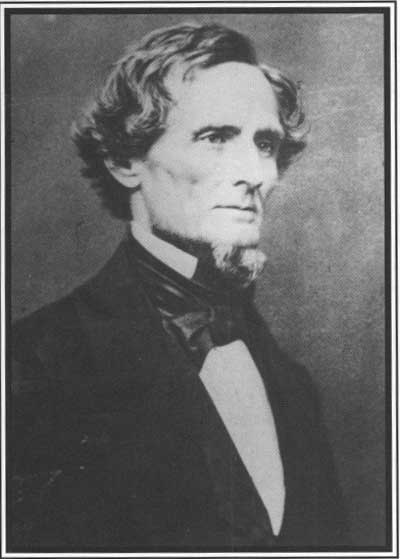

JOSEPH EGGLESTON JOHNSTON, 1807-1891. Johnston attended West Point

with both Jefferson Davis and Robert F. Lee, graduating with Lee in

1829. He was wounded in every war that he fought, starting with the

Seminole War, and in Mexico he was shot five different times. He served

as an engineer in peacetime until 1855, when he was assigned to a

mounted regiment as lieutenant colonel. In that capacity he served

through the Kansas troubles and the Mormon expedition, but in the summer

of 1860 he was appointed quartermaster general of the U.S. Army.

Johnston resigned that post ten months later, taking command of

Confederate troops at Harpers Ferry. His little army arrived in time to

help win the first battle at Manassas, after which Johnston was promoted

to full general and given command of the troops in northern Virginia.

Taking his army south to defend Richmond, Johnston was severely wounded

at the battle of Seven Pines, and he remained inactive until given

nominal command over all troops between the Tennessee and Mississippi

Rivers.

This frustrating assignment was marked by repeated failures, largely

because President Davis overruled Johnston, but at the end of 1863

Johnston was given direct command of the shattered Army of Tennessee.

Davis grew annoyed when Johnston met Sherman's advance on Atlanta with

defensive strategies, and late in July he replaced him with the more

aggressive John Bell Hood. Johnston again assumed command of what

remained of that army in February of 1865, jousting ineffectually with

Sherman's much larger army until he was forced to surrender on April 26.

Johnston was one of few senior Confederates who realized that offensive

tactics would drain limited Southern manpower, and his foresight led to

constant friction between him and President Davis.

ROBERT E. LEE, 1807-1870. The son of a renowned Revolutionary War

soldier, Lee took second place in the West Point class of 1829,

graduating without having accumulated a single demerit. Serving as an

engineer for most of his career, he was one of Winfield Scott's most

trusted staff officers during the Mexican War. He was superintendent of

the military academy for three years, after which he was appointed

colonel of a cavalry regiment on the frontier, but he spent much of that

assignment on leave of absence. He commanded a detachment of U.S.

Marines and stray soldiers who stormed John Brown's bastion at Harpers

Ferry in 1859, and he had just returned to his cavalry regiment in Texas

when secessionist troops forced him to return east.

Named one of the five original full Confederate generals, Lee served

a few dismal months in western Virginia and on the coast of South

Carolina before taking command of the Army of Northern Virginia on June

1, 1862. His three years at the head of that army made him a legend as

he first drove the Federals from the gates of Richmond, pushed them back

into northern Virginia, and twice invaded the North.

In the end many of his soldiers seemed to cling to the army out of

personal loyalty to the general himself.

|

Lee's boldness and sheer luck nearly brought the European recognition

that might have saved the Confederacy, but his aggression also cost

heavy casualties that the South could ill afford, and in the final year

of the war he was forced to follow a defensive strategy, though he still

attacked ferociously now and then within the confines of that strategy.

In the end many of his soldiers seemed to cling to the army out of

personal loyalty to the general himself.

THOMAS JONATHAN JACKSON, 1824-1863. Though he never commanded a large

independent army, "Stonewall" Jackson is far more famous than most of

those who did. A graduate of the West Point class of 1846, he served

with distinction as an artilleryman in Mexico, resigning in 1851 to

teach at Virginia Military Institute. Unimpressive as a professor there,

he was often ridiculed by the cadets, who were puzzled at his personal

idiosyncrasies.

Appointed a Confederate brigadier general in June of 1861, Jackson

led a brigade at First Bull Run that stemmed a Union onslaught and put

the enemy to his heels. There he earned his nickname and a slight wound

to the hand. The following spring, with about 10,000 men, he began a

campaign against three Union armies in the Shenandoah Valley, defeating

them all at one time or another by virtue of rapid movements and

surprise attacks; his maneuvering tied up some 70,000 Federals who might

otherwise have taken part in the movement against Richmond. Afterward he

served with Robert E. Lee in the Army of Northern Virginia.

He inspired his men with repeated successes rather than with his

person presence or attention, and his name came to strike terror in the

hearts of Union soldiers.

|

During the Seven Days Jackson put in a lackluster performance, but at

Second Bull Run he shone again, holding against the more powerful Union

army until the rest of Lee's troops could execute a decisive flank

movement. He captured Harpers Ferry and 12,000 Federal soldiers during

the Maryland campaign and staved off superior forces at Fredericksburg,

but his greatest battle was Chancellorsville, where he led a wide

flanking movement that crumbled the flank of the overwhelming Union

army. There Jackson was mortally wounded, though, and he died eight days

later. Laconic, dyspeptic, and secretive, Jackson was unsympathetic to

his enemy and his troops alike. He inspired his men with repeated

successes rather than with his personal presence or attention, and his

name came to strike terror in the hearts of Union soldiers.

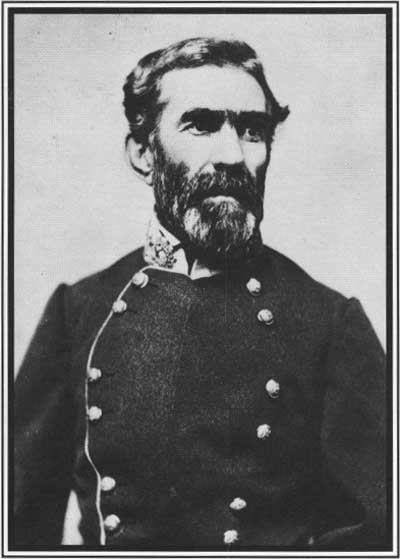

BRAXTON BRAGG, 1817-1876. After graduating near the top of the class

of 1837 at West Point, Bragg spent nine teen years on active duty. As an

artillery officer he fought in the Seminole War and in Mexico, most

notably at the battle of Buena Vista, where his battery helped repel a

key Mexican attack. After the war his battery was assigned to New

Mexico, but Bragg served instead on staff duty. He finally resigned in

1856 to manage a plantation in Louisiana, but he was appointed a

brigadier general in the Confederate army five weeks before the Civil

War began.

Bragg commanded a wing of the army at Shiloh, and late in June of

1862 he took command of the Army of Tennessee, which he retained for

seventeen unfortunate months. During a poorly coordinated invasion of

Kentucky that autumn, Bragg missed an opportunity to fight the enemy on

his own terms, and eventually he was forced to abandon everything he had

gained. At Stones River he surprised the stronger Federals but failed to

crush them, despite enormous casualties on both sides. His only real

victory came at Chickamauga, but he was unable to break down the Union

rear guard and scatter the retreating foe. His humiliating defeat at

Chattanooga two months later led to his promotion to military adviser

for President Davis.

Though extremely argumentative with subordinates and equals, Bragg

got along well with Davis, and he served the Confederacy far better in

this administrative capacity than he ever had on the battlefield. Toward

the end of the war he accepted another field command, taking a corps in

the army he had once led, and with that he participated in the final

defeats in North Carolina.

JOHN BELL HOOD, 1831-1879. A contemporary of Philip Sheridan, Hood

graduated near the bottom of his class at West Point in 1853, He fought

Indians as an infantryman until he resigned from the army in April of

1861.

Though a Kentuckian himself, early in 1862 Hood took command of a

Texas brigade, with which he broke the Union line at Gaines's Mill,

during the Seven Days' battles. He led this brigade at Second Bull Run

and Antietam, after which he was given a division. At Gettysburg he

suffered a wound that crippled his left arm, but ten weeks later he

returned to the front at Chickamauga, where he lost his right leg.

The wound would have put a less combative man out of the war, and it

might have been better for the Confederacy if Hood had retired, but when

the Atlanta campaign began, early in May, he took his place at the head

of a corps, though he had to be strapped into the saddle. Preferring the

offensive despite dwindling Confederate resources, Hood criticized

Joseph Johnston's more cautious strategy, and the equally aggressive

President Davis finally displaced Johnston in favor of Hood on July 17.

In three days of fruitless hammering at the advancing Federals Hood lost

more men than Johnston had during the entire campaign. Finally Hood

allowed Sherman's army to encircle Atlanta completely, and Hood

responded by swinging back on Sherman's line of communications, which

allowed Sherman to proceed virtually unmolested across Georgia.

Doubling back to Tennessee, Hood sacrificed one-sixth of his army and

his best division commander in an unsuccessful effort to eliminate part

of the Union army at Franklin, and two weeks later his army was

virtually destroyed at Nashville. In January of 1865 he asked to be

relieved of command, which essentially ended his Confederate career.

|

It was often overlooked even at the time that all the while the Union

waged its war to rebuild itself, it was also pushing its borders further

west, admitting new states, beginning the preliminaries that led to the

first transcontinental railroad, and after 1863 creating the land grant

colleges that later became many of the nation's great state

universities. Lincoln also conducted a remarkably successful foreign

policy, aimed chiefly at keeping other nations out of the war, helped

bring about a small social revolution by the enlistment of free Negroes

into black regiments, and brought about substantial changes in the

nation's economy, including the not exactly popular institution of the

first income tax. By 1864 the war was costing $4 million a day, a

staggering expense undreamed of before 1861, and a reflection not only

of the magnitude of the war itself but also of the national expansion

and organization that took place during the conflict. The Union was on

its way from being a major power in its hemisphere to becoming a major

power on the globe. Almost literally, Lincoln fought the Confederacy

with one hand while he oversaw the transformation of the United States

with the other.

|

MEN OF COMPANY E. 4TH U.S COLORED INFANTRY AT FORT LINCOLN. (LC)

|

|

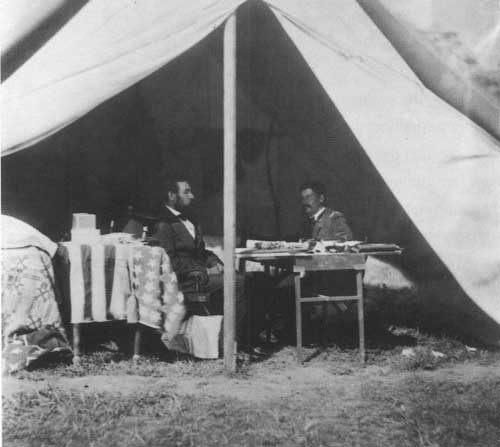

THE PRESIDENT CONFERS WITH GENERAL GEORGE B. MCCLELLAN. (LC)

|

By the end of 1862, events in the war in the eastern theater might

have suggested that Lincoln use both hands for his war, for the story of

defeat that began the war at Fort Sumter and Bull Run continued almost

without letup. Following the retreat of his army to Washington, Lincoln

brought a new man to its command, McClellan, who had made a name for

himself with some very minor successes in western Virginia. "Little

Mac," as his men affectionately called him, had the gift of inspiration

and proved to be perhaps the finest organizer of the war. He rebuilt the

demoralized army, soon to be called the Army of the Potomac. He selected

officers almost as inspiring as himself, gave the men renewed pride in

themselves, equipped them magnificently, drilled them to a degree

unheard-of among volunteer troops, and in all turned them into the most

impressive military body ever seen on the continent by early 1862.

Fortunately, the war stayed quiet in Virginia for months after Bull Run,

giving him time to do all this, but as the spring of 1862 approached,

Lincoln and the Union expected McClellan to use this wonderful army.

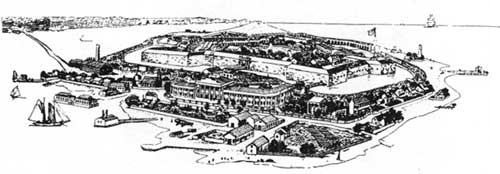

McClellan's plan looked brilliant when presented. He wanted to put

his army aboard transports and steam down the Potomac to Chesapeake Bay,

then south to Fort Monroe, a massive fortification at the tip of the

Virginia peninsula formed by the James and York Rivers. Monroe was too

strong for the Confederates to drive its Union garrison out, and so it

sat like a knife poised at the back of Richmond. McClellan would use it

as his base, land his troops, and march up the Peninsula to attack and

take Richmond from the rear. If he moved quickly, he could end the war

in the East in a few weeks.

|

FORT MONROE (BL)

|

|

GENERAL JOSEPH E. JOHNSTON (LC)

|

It all went wonderfully until McClellan landed. Then he showed the

other side of his generalship—timidity, a tendency to exaggerate

the size of the enemy before him, and a dread fear of responsibility in

case of defeat. Opposed to him at first were only a few thousand

Confederates at Yorktown. With more than 60,000 men ashore and more

coming every day, McClellan could have walked over them. Instead, he

stopped to prepare a siege. That gave Confederates time for the rest of

their army, commanded by Johnston, to come to the scene. In the end

Johnston would still have no more than 60,000 men while McClellan

commanded more than 100,000. But throughout the campaign that followed,

instead of moving quickly and taking advantage of his superiority,

Little Mac stalled, stumbled, and consistently believed that the Rebels

outnumbered him.

In fact, throughout April and most of May, McClellan advanced only

because the equally timid and fearful Johnston pulled back before him

without a fight. Not until May 31 did they finally meet in real battle

at Seven Pines, where Johnston took a serious wound that put him out of

the war for months. President Davis gave the command to Robert E. Lee,

his chief military adviser, and now the Confederates had a commander

worthy of their valor. Thereafter Lee completely dominated the campaign.

Stonewall Jackson had just finished an electrifying campaign a hundred

miles to the west in the Shenandoah Valley, where his small force had

decisively met and defeated three separate Federal forces and driven

them from the Valley and its vital agricultural resources. Lee now

summoned him to Richmond, and together they struck at McClellan on June

25, commencing what were called the Seven Days' Battles. Day after day

until July 1 Lee struck, and while he never obtained the decisive

victory he sought, still he so overwhelmed McClellan that the Federals

finally pulled back toward Fort Monroe and eventually withdrew entirely

without offering battle again.

Little Mac's reputation was severely tarnished, but Lee's rose to the

forefront, and through the balance of the year he polished it the

brighter. While McClellan stumbled on the Peninsula, Washington built

another command called the Army of Virginia, designed to protect it

while McClellan's army was away. In late July its commander, General

John Pope, led it south in the hope of drawing Lee away from Richmond to

allow Little Mac to advance once more. But Lee knew that McClellan would

not budge and sent Jackson to stop Pope. At Cedar Mountain on August 9

Jackson struck a devastating blow that turned back one of Pope's corps,

and then Lee, seeing that McClellan was starting to abandon the

Peninsula, took the balance of his army to reinforce Stonewall. On

August 28-30, along the banks of Bull Run and on some of the same ground

where the battle of the year before had been fought, Lee and Jackson

soundly defeated Pope, though this time the Federals did not run in

demoralization. Nevertheless, the sting of these defeats following hard

or one another badly humiliated McClellan—who withheld much-needed

support from Pope, ruined Pope himself, and stunned the North.

|

LIEUTENANT GENERAL ROBERT E. LEE (USAMHI)

|

|

BRIG. GEN. JOHN POPE (CWL)

|

|

MECHANICSVILLE, VIRGINIA, SITE WHERE THE SEVEN DAYS' BATTLES BEGAN.

(CWL)

|

Lee and Davis sensed that this was the perfect time to launch an

invasion of the Union, It would further disorganize Yankee morale and

give northern Virginia some relief from the exhausting presence of the

armies. He led his newly designated Army of Northern Virginia across the

Potomac in early September and drove into Maryland. McClellan, by now at

nearby Frederick, encountered a monumental stroke of luck when a copy of

Lee's plan of campaign fell into his hands, but he moved slowly to

capitalize on it, and the two armies did not meet each other until

September 17. Still, Little Mac caught Lee at a disadvantage, with much

of his army several miles distant and the remainder backed up against

the Potomac near Antietam Creek. Fortunately for the Confederates,

McClellan conducted a miserable battle, wasting time, making piecemeal

attacks with parts of his army instead of taking advantage of its

numerical superiority. In the end, after what proved to be the bloodiest

day of the whole war, with almost 5,000 killed between the two armies,

the balance of Lee's army arrived in the last moment and he held his

ground rather than be pushed back into the river. Typically, Lee wanted

to fight again the next day, but McClellan had no stomach for it, and

Lee, who was still in a very precarious position, had no choice but to

retire to Virginia.

Because the Federals held the field and Lee retreated, the Union

claimed Antietam as a victory, though if anyone should be counted the

victor it was Lee for saving his army from such a dangerous position.

Still, it was Lincoln's first success in the East, and he used it as the

pretext for his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. But it would be

McClellan's last battle. Fed up with the general's sloth and

haughtiness, Lincoln replaced him on November 7 with General Ambrose

Burnside. This handsome and well-liked officer would last through only

one battle as a commander before he, like McClellan, learned just how

formidable Lee and his army could be. Burnside advanced into Virginia

toward Fredericksburg, on the Rappahannock River, barely fifty miles

from Richmond, and there planned to cross and move on the Rebel capital.

Lee was waiting for him, well entrenched on the southern side of the

river, and when Burnside attacked on December 13, the Confederates

summarily stopped his campaign. Delays in getting the pontoon bridges

that he needed to cross the river lost Burnside valuable time, and when

he did get his bridges erected—under fire—and his men across

the river, Lee pinned them down in the streets of the city or met them

with withering fire as they attacked up a slope. In the end, after

suffering more than 12,000 casualties, Burnside gave up.

|

DEAD SOLDIERS OUTSIDE DUNKER CHURCH AFTER THE BATTLE OF ANTIETAM. (LC)

|

|

GENERAL AMBROSE BURNSIDE (SEATED, CENTER) AND STAFF PICTURED AT ARMY OF

THE POTOMAC HEADQUARTERS. (CWL)

|

|

PERIOD PAINTING OF THE BATTLE OF SHILOH. (LC)

|

|

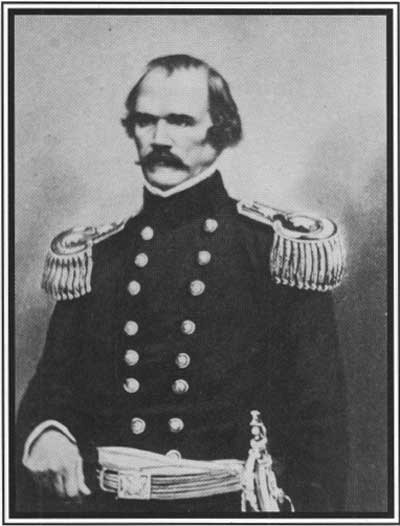

GENERAL ALBERT SIDNEY JOHNSTON (CWL)

|

If Union fortunes in the East looked grim as the end of the year

approached, they appeared a bit better in the West. In fact, the same

Grant who failed at Belmont started the year with a significant victory

in the taking of Forts Henry and Donelson, which guarded the lower

reaches of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers. These streams emptied

into the Ohio in Kentucky, but their upper reaches passed through all of

central Tennessee and northern Alabama. Yankee gunboats having access to

them could steam clear into the heart of the Confederacy and actually

get in the rear of Southern forces in Nashville and elsewhere. By taking

the two forts, Grant stood poised to do just that. As a result, the

Confederate commander in the region, Davis's bosom friend General Albert

Sidney Johnston, had no choice but to evacuate Tennessee to avoid being

cut off. He pulled into northern Mississippi, but then planned a

campaign to regain the territory he had lost. In late March he moved

north again and on April 6 almost completely surprised Grant and his

army camped near Pittsburg Landing, on the Tennessee. In the most

furious day's fighting yet seen in the West, Johnston struck all along

Grant's line. The struggle blazed in places with names like the Peach

Orchard, the Hornets' Nest, and beside Shiloh church. Johnston pressed

the Yankees almost back into the Tennessee itself. But then Johnston

fell from his saddle in a swoon and soon died. He bled to death from a

bullet wound in his leg that he foolishly ignored. Command shifted to

his second, Beauregard, who had been sent west chiefly because he and

Davis could not get along, and the new general almost immediately lost

his resolve. This, and large reinforcements during the night, saved

Grant, so that on April 7, he was ready to take the initiative, and by

the end of the day Beauregard was in retreat.

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL BRAXTON BRAGG (LC)

|

|

MAJOR GENERAL WILLIAM ROSECRANS (LC)

|

Hard on this success, Captain David G. Farragut's Union fleet steamed

up the Mississippi, past the forts guarding New Orleans, and on April 25

captured the city. This gave the Union control of the lower Mississippi

as well as the upper river, leaving the South only a hundred miles or so

of the stream between Mississippi and Arkansas and north Louisiana. Once

the Yankees gained complete mastery of the great river—if they

did—they would divide the Confederacy in two, isolating Texas,

Arkansas, and western Louisiana from the rest of the seceded states.

Slowly, just as in the taking of the Tennessee and Cumberland the

Yankees were carving the western Confederacy into slices by taking and

using its rivers.

The summer and fall of 1862 saw Grant and Farragut attempting to

close off the rest of the Mississippi, but the fortress city of

Vicksburg defeated their efforts. Meanwhile, Beauregard left his

command, and General Braxton Bragg took command of what was now termed

the Army of Tennessee. Moving in tandem with Lee's invasion of Maryland,

Bragg moved north in August hoping to retake middle Tennessee and push

into Kentucky, where he believed he would find large reinforcements

among Southern sympathizers. Instead, he found Kentuckians largely

indifferent to Confederate interests and more loyal to the Union than he

supposed. He got as far as the capital at Frankfort before a Union army

led by Don C. Buell began to threaten his line of retreat. Rebuffed by

Kentuckians, Bragg turned back, and at Perryville in October the two

armies fought an inconclusive engagement that still left Bragg with no

alternative but to continue his withdrawal.

In the end, Bragg pulled back to central Tennessee, while the Yankees

followed him as far as Nashville. For two months they refitted

themselves and planned their next move, and then a new commander,

William Rosecrans, led Buell's Army of the Cumberland south to attack

Bragg in December. Bragg met him in and around the small town of

Murfreesboro, along Stones River on December 31. For several hours the

armies hammered each other bloodily, and that evening Bragg wired

Richmond that he had won a great victory. The unending tale of defeat

for the Union seemed to roll onward without relief.

|

KURZ AND ALLISON PRINT FROM 1891 OF THE BATTLE OP STONES RIVER. (LC)

|

|

RUINS IN FREDERICKSBURG AFTER BOMBARDMENT IN DECEMBER 1862. (LC)

|

December 1862 was the high tide of the Confederacy. Never in all its

brief history did its prospects look brighter. Lee stopped Burnside at

Fredericksburg and was already showing himself to be the master of any

general the Yankees could send against him. Despite the loss of Albert

Sidney Johnston in the West and Bragg's repulse in Kentucky, the year

ended with Lee at the verge of sending Rosecrans back north in defeat.

Though much of the Mississippi fell to the enemy, still Vicksburg held,

as did Port Hudson a hundred miles south, keeping communications open

with the Trans-Mississippi Confederacy and its rich resources of men and

supplies. In Richmond Jefferson Davis had a government up and operating,

men still turned out with gusto to fill his regiments, and though

hard-pressed for weapons and money and every other article needled to

wage war, the Confederacy was still doing it thanks to the high resolve

of its people.

The infant nation had come a long way from the day back on February

4, 1861, when 47 delegates from South Carolina, Georgia, Florida,

Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana met in Montgomery, Alabama, to form

a defensive alliance. In four hectic days they formed a preliminary

constitution based on the old United States Constitution, adding an

article that specifically recognized the inalienable right to own

property in slaves. Then they chose a president. Everyone expected him

to be a Georgian because that state was a powerhouse of political

leaders, including Robert Toombs, Howell Cobb, and Alexander H.

Stephens. But Cobb had been too vacillating on Southern rights in the

past. Toombs could not hold his liquor and became embarrassingly drunk

just a night or two before the election. And Stephens took himself out

of the running, saying he had been too ardent a Unionist in the past for

Confederates to accept him now as their leader. Only on the last evening

before the election did the delegates settle on Jefferson Davis of

Mississippi, and on February 8 they elected him unanimously, making

Stephens his vice-president.

|

PRESIDENT OF THE CONFEDERACY JEFFERSON DAVIS (USAMHI)

|

|

COTTON BALES ON THE DOCKS OF CHARLESTON HARBOR. (SOUTH CAROLINA

HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

The task before him dwarfed even the Herculean challenge facing

Lincoln. To get his government going, Davis almost literally stole much

of it from the Union. More than one of his cabinet secretaries persuaded

Southern sympathizers working in similar departments in Washington to

come south, bringing their staffs and even their office forms with them.

Secretary of the Treasury Christopher G. Memminger began announcing

subscription loans to raise money for the government, and in the end

Confederates contributed tens of millions in return for interest-bearing

bonds to be redeemed after a successful conclusion of the war. The Post

Office Department put itself in a position to be entirely

self-sustaining and eventually returned a profit by reducing services

and raising rates.

The founding fathers of the Confederacy saw themselves not as rebels,

but as reformers. They did not try to establish some radical new form of

government. They wanted the constitutional democracy they felt that had

had all along until the balance of power shifted to the North. They

wanted free trade with the world rather than a high tariff that

protected certain—Northern—industries. They opposed spending

the revenues raised from one state to make "internal improvements" or to

encourage an industry in another state. They wanted the Constitution

strictly obeyed in its literal intent and not "interpreted" to expand

the powers of central government. And they wanted the sovereignty of the

states recognized in all those matters in which they did not

specifically grant power to the nation. Most especially, of course, they

wanted protection for slavery.

Yet these men proved to be idealists in a way, too. Having seen all

of the sectional discord caused by party politics, especially when the

entirely sectional Republican Party rose to prominence, they dreamed of

a nation and a government without parties. In February 1861 they could

have such dreams, since in the excitement, euphoria, and fear of the

time, men of all stripes seemed united to the one goal of Southern

unification and defense. Unfortunately, it could not last. An opposition

immediately arose, headed by men whose disappointed ambitions for high

office made them instinctive enemies of Davis and his policy. Then there

were those who favored an aggressive prosecution of the war, while Davis

and the majority knew that the South was not equipped to do more than

maintain a spirited defensive. Soon the state governors got into the

fray, increasingly standing in Davis's way when he tried to get troops

and supplies from them. They would willingly turn over their regiments,

of course, but they refused to recognize the right of the government to

command them to do so. Within only a few months of the formation of the

Confederacy, the very doctrine of localism and states' rights that lay

at its core began working against it. By early 1862, these elements and

more, though they had no other issues to unite them, began to bond on

the single matter of hostility to Jefferson Davis. In time, the

partyless Confederacy had a second party after all, one with no name and

but a single credo, to thwart the president. Happily, they never managed

to do more than interfere. They never stopped any of his efforts, and

even in the Congress, which by 1864 had a sizable minority of anti-Davis

members, his majority remained safe enough that only one of his vetoes

was ever overridden, and that was one of minor importance. Battered,

abused, and maligned, still Jefferson Davis remained in command of the

Confederacy from beginning to end and left his personal stamp on its

history—for good and ill—even more than did Lincoln on the

Union.

|

|