|

|

MACHINES OF WAR

by William Marvel

War tends to bring out the inventiveness of those whose countries

fight, and the American Civil War was no exception. Many of today's

sophisticated weapons and tools of war are the direct descendants of

inventions that saw their first successful employment in the Civil

War.

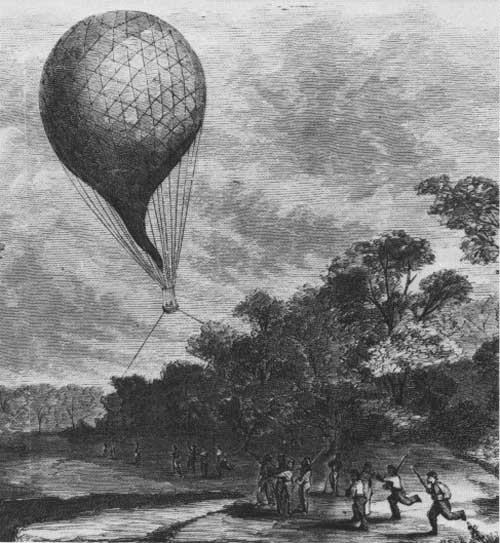

One of the earliest innovations employed by either side was the

observation balloon. Balloons had seen some limited use in Europe a

couple of generations earlier, but they had not caught on. As early as

the spring of 1861 Thaddeus S. C. Lowe convinced the Federal government

to test the potential of his hydrogen balloon, and on June 18 he

ascended from the grounds of the Smithsonian Institution and relayed his

observations to the ground by telegraph. The War Department hired him,

and by November his apparatus was operating on the Potomac River from

the deck of a coal barge towed by a steam tug. This was not the earliest

employment of such an aircraft carrier, though, for the U.S. steamer

Fanny carried a balloon within sight of Norfolk the previous August. The

Confederates also used a ship board balloon during the Seven Days'

campaign in 1862, watching Federal forces while Lowe's aeronauts

observed from the opposite side.

|

SKETCH OF FEDERAL OBSERVATION BALLOON SCOUTING REBEL POSITIONS. (LC)

|

The Civil War saw the introduction of land mines, hand grenades, and

battlefield telegraphs, but the most significant efforts went into the

production of firearms: the rifles that helped win this war changed the

face of warfare forever. President Lincoln sometimes tested new weapons

himself, and in the summer of 1861 he authorized two regiments of

sharpshooters armed with breechloading rifles: these could be fired much

more quickly than the muzzle-loading standbys, and shorter

breech-loaders proved especially useful for cavalry. Most of the

breech-loaders fired a metallic cartridge, which in turn allowed for the

development of repeating rifles.

The most popular repeater was the Spencer, which was fed through a

tubular magazine inserted in the stock. With a Spencer carbine, a

horseman could fire seven rounds as quickly as he could cock the hammer

and pull the trigger, and he could reload in less time than it took his

enemy to cram a charge down the barrel of a rifle. The less common

Henry, a lever-action rifle produced by the company that became

Winchester, could fire sixteen rounds without reloading.

In 1862 Richard Gatling produced a carriage-mounted gun with several

revolving barrels. Bullets were fed through a hopper atop the gun, and

as the gunner turned a handcrank the barrels moved into place like the

chambers of a revolver, The Gatling gun could fire 150 rounds a minute,

and the multiple barrels allowed a couple of seconds for each one to

cool before it was fired again. The same system was employed in the

miniguns of Vietnam renown.

The first periscope was patented in 1864. It was used by infantry

officers in their trenches, rather than by naval forces, but naval

warfare was likewise transformed by Civil War innovations. Most

obviously, the meeting of the USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia sounded

the death knell of wooden warships. Both sides came to rely more on

ironclads thereafter, though Southern shipbuilders had to improvise

cumbersome rams from railroad iron by the waning months of the war. With

iron ships came other inventions, like the revolving turret, which

remains in use at sea today.

While impractical submarines had been used as early as the American

Revolution, the first ship sunk by one was the USS Housatonic, which

went to the bottom on February 17, 1864, off Charleston, With her went

the hand-propelled Confederate submarine Hunley, which had been

extemporized from two steam boilers. Sailors also learned to fear

underwater mines for the first time in history, and the ironclad Federal

gunboat Cairo became the first victim of one on December 12, 1862, in

the Yazoo River, near Vicksburg.

|

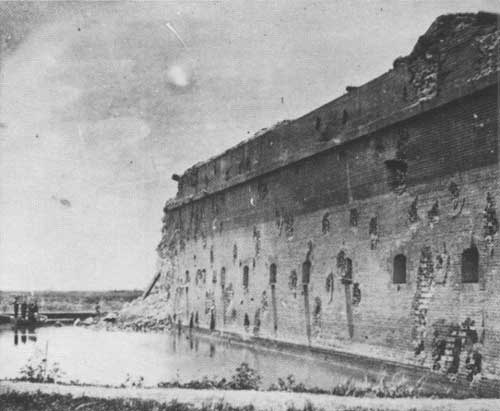

THE FEDERAL BOMBARDMENT OF FORT PULASKI WITH LONG RANGE GUNS ENDED

FORTIFICATION ARCHITECTURE AS THE WORLD HAD KNOWN IT. (NPS)

|

Some of the Civil War's technological developments were devoted to

the amelioration of war's effects. The first soldier to lose a limb in

battle—a Confederate wounded on June 3, 1861—used barrel

staves and some common hardware to fashion an ingenious artificial leg,

and he spent the rest of his life manufacturing prostheses based on his

original design. The first orthopedic hospital opened in New York City

on May 1, 1863, at least partly to respond to the sheer mass of human

wreckage from the battlefield. Perhaps with an idea of saving nearby

Fort Monroe in case it were attacked with incendiary shells, the

postmaster at Old Point Comfort, Virginia, invented the first fire

extinguisher in 1863.

Industrial development accelerated as a result of wartime demands.

The first Bessemer steel converter went into commercial production in

Michigan in 1864, and the first steel railroad track was laid in

Pennsylvania that same year. Heavy troop and freight traffic led to the

installation of the first railroad signal system between Philadelphia

and Trenton in 1863, The first oil pipeline was completed in 1863, and a

year later came oil tank cars.

After 1865, armies would not march abreast at an enemy, fire a

volley, and charge with the bayonet. Never again would the crews of

powerful ships enjoy complete security. In four brutal years,

technological development had advanced decades, and the war that changed

America changed the world.

|

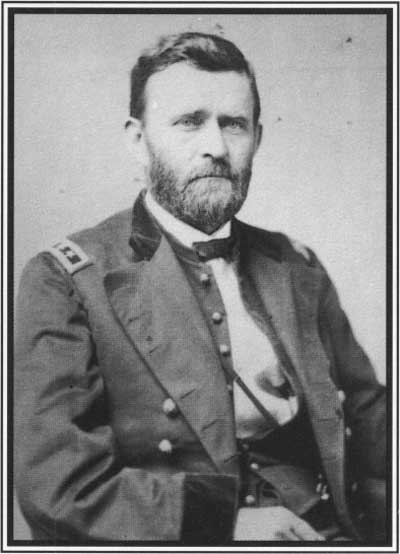

Indeed, by 1864 it was that determination to press on, despite

setbacks or dangers, that came to characterize the Union war effort,

thanks chiefly to Grant. In March Lincoln brought him to the East and

made him general-in-chief of all Union armies, charged to direct a

coordinated offensive from Virginia to the Mississippi and beyond. It

would be the first time that a single guiding hand exerted absolute

control over the several armies wearing the blue, and Lincoln now felt

convinced that in Grant he had the man with the right grip. If he could

keep all Confederates fully engaged on all fronts, no more

reinforcements could move from one army to another as happened at

Chickamauga. Moreover, in this way Grant could wear the Rebels down,

taking advantage of Union superiority in manpower, material, and

everything else. He was no butcher planning a war of attrition by

trading the lives of his men for those of the enemy in order to win. But

he knew what his predecessors had failed to grasp, that superiority was

worthless unless a commander used it again and again. There would be no

turning back from now on. Yes, he and his generals would suffer

setbacks, defeats even. But they would never again run back to

Washington after a bad battle. Win or lose, they would press on. It was

a strategy that even the valor and wit of the Confederates could not

withstand indefinitely.

|

LIEUTENANT GENERAL ULYSSES S. GRANT (USAMHI)

|

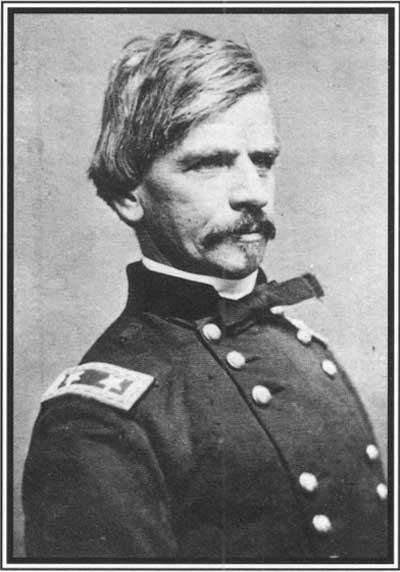

Grant assigned General Nathaniel P. Banks to lead a small army up the

Red River of Louisiana to occupy Confederates in the Trans-Mississippi.

Meanwhile, his most trusted subordinate, William T. Sherman, assumed

command of three armies combined into an army group, his task being to

drive south out of Chattanooga and strike through Georgia to the rail

center at Atlanta. That done, he could press on eastward across Georgia

to strike Savannah and then move up the coast against Charleston,

eventually ending up in North Carolina or even Virginia. His move would

carve the southeastern Confederacy in two and disrupt or destroy the

already shaky remaining Confederate rail and supply communications. As

for Grant, he would go east and move with Meade and the Army of the

Potomac, their goal being not Richmond this time but Lee's army itself.

With a small force commanded by General Franz Sigel moving at the same

time to take the Shenandoah Valley, there would be no place in the

Confederacy safe from the threat of invasion or Confederate soldier not

constantly committed to battle in his front.

Grant got a mixed bag of success and failure, but fortunately for the

Union, the failures came where they mattered rather little. Banks, like

Sigel, was a commander forced on by expedience. Both Lincoln and Davis

had to try to appease political factions within their domains by doling

out military commissions to men with no real experience or training at

warfare. Called "political generals," more often than not these men

proved woeful failures. Banks had been around since the beginning of the

war and was one of the commanders beaten by Stonewall Jackson in the

Shenandoah in 1862. Now he conducted an inept campaign up the Red River,

accompanied by thirteen ironclads and a number of other gunboat, and

with a total of around 40,000 troops at his disposal in three different

columns. Facing him, Confederate General E. Kirby Smith had perhaps

30,000 men, widely scattered over his vast Trans-Mississippi command.

Banks got as far as Alexandria to discover that low water on the Red

River would make it difficult for his fleet to continue. Nevertheless,

he pushed on, intending to follow the withdrawing Rebels to Shreveport.

But then the Southerners handed him a sharp setback at Sabine Cross

Roads on April 8. Banks retaliated with a small victory of his own the

next day at Pleasant Hill but then decided to give up his campaign and

retreat. By now the Red's depth had fallen further, and Captain Porter

found that he could not get his fleet back down the river along with

Banks's retiring army. Only ingenuity on the part of an engineer who

built artificial dams to raise the level temporarily allowed the fleet

to pass by. The campaign ended as a fiasco, and Banks himself finally

was relieved of command in May, a result almost worth the cost of a

failed expedition.

|

MAJOR GENERAL NATHANEL P. BANKS (USAMHI)

|

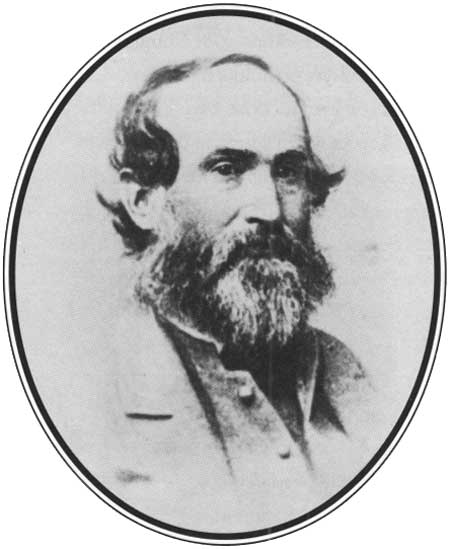

The same could have been said for Sigel, a prominent immigrant with a

large following in the German population of the North. He gained high

command because of his influence at enlisting other immigrants to the

cause, but he was trouble wherever he served. In May 1864 he led his

small army south into the Shenandoah hoping to ravage the valley called

the "bread basket of the Confederacy." He conducted an even more inept

campaign than Banks, however, moving too slowly, weakening his command

in the face of small Confederate feints, and finally arriving near New

Market, Virginia, with an army little more than half the size of what he

started with. His opponent, another political general who proved to be

the exception to the rule, was John C. Breckinridge, once vice president

of the United States, and a very capable commander. Putting together a

scratch force of Confederate volunteers partisans, home guards, and even

the students from the Virginia Military Institute, he met Sigel on May

15. Sigel foolishly split his army, with the result that though he

outnumbered Breckinridge by three to two or better, in the actual

fighting Breckinridge met him on even terms by using every man and boy

at his command, They fought all day in the rain, and in the end

Breckinridge sent Sigel fleeing back north in panic. Sigel, too, would

be replaced, and in June his successor, David Hunter, came back and this

time ravaged the Shenandoah.

|

SKETCH BY CIVIL WAR ARTIST ALFRED WAUD OF WOUNDED SOLDIERS ESCAPING FROM

THE BURNING WOODS OF THE WILDERNESS. (LC)

|

|

GENERAL EDMUND KIRBY SMITH (CWL)

|

|

MAJOR GENERAL FRANZ SIGEL (USAMHI)

|

Elsewhere in Virginia, however, the daily headlines told a different

story. On May 4 the 100,000-strong Army of the Potomac under Meade

crossed the Rappahannock once more and marched into the dense woods

where Hooker met defeat at Chancellorsville exactly a year before. But

this time these men were led by Meade and with him the even more

resolute Grant. During the next three days the heavy terrain called "the

Wilderness" hampered and baffled their attempts to get through, with Lee

and a mere 61,000 before them. Lee conducted a masterful defense and in

the end stopped Grant's progress.

|

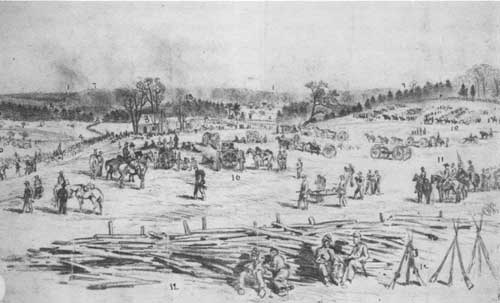

PERIOD DRAWING SHOWS THE CENTER OF THE UNION POSITION AT SPOTSYLVANIA

COURT HOUSE. (LC)

|

|

BOMBSHELL EXPLODES DURING RATTLE AT COLD HARBOR, FROM A SKETCH MADE AT

THE TIME. (BL)

|

But gone were the days when a repulse ended a campaign. Grant and

Meade decided on the night of May 7 that if they could not push through,

they would simply go around. And so the Yankees stepped back and shifted

to their left, hoping to get between Lee and his supply and

communications line to Richmond. Lee stayed with them and met the

Yankees next at Spotsylvania. During almost two weeks to follow, Grant

maneuvered and attacked again and again, and Lee countered him each

time. May 9 and 10 Grant hit Lee's left, then nearly pierced his center.

May 12 Grant attacked again along much of the line, and yet once more on

May 18, even as Lee extended his own line southward to meet Grant's next

expected try to get around him, Grant was undeterred. He just kept

shifting to his left and south and met Lee again for five days along the

North Anna River.

Grant was taking heavy casualties by now, but so was Lee, and with

every shift the Yankees got closer to Richmond. Lee was beginning to

realize that if he could not stop Grant's progress in the open field, he

would be forced eventually back into the defenses of Richmond itself.

Once Lee's army was there, unable to maneuver, Grant's numerical

superiority must inevitably allow him to surround the city and lay

siege. Once that happened, Lee warned Davis, it would be but a matter of

time.

Once more Grant failed to penetrate Lee's defenses, and on May 26 he

pulled back and moved southward to Totopotomoy Creek and then on to Cold

Harbor, Lee all the time in his front. Now Grant had moved, without

winning a battle, all the way to the eastern environs of Richmond. Lee

had to stop him at Cold Harbor, and stop him he did. On June 3, himself

frustrated by now at his inability to bring Lee to bay, Grant decided on

a tactic he had not tried before and that Lee's own experience at

Gettysburg suggested would not work. He ordered a massive frontal

assault against the right and center of the Confederate line, in a

movement that he would later confess he regretted. In less than an hour

of bitter fighting, he took 7,000 casualties without making a

sustainable breakthrough in the Rebel line, and in the end he ordered

the engagement broken off. Once more Lee had saved Richmond and his own

army.

Even after this terrible reverse, however, the Yankees stood their

ground. Stunned by the magnitude of the repulse and exhausted by their

month of campaigning and almost daily fighting, the bluecoats waited and

caught their breath. Then Grant pulled on Lee his greatest surprise of

the war. On June 15, without the Confederates knowing it, Grant's

engineers built a pontoon bridge across the James River below Richmond.

In eight hours his engineers created a 2,200-foot span, and soon

afterward, undetected by Lee, Grant pulled his army out of its position

at Cold Harbor and marched. it across the bridge. At once he drove

toward the vital rail and supply center at Petersburg, the back door to

Richmond barely twenty miles north. Only the fact that his exhausted

army could not move as it once did and the bumbling of his commanders on

the scene prevented Grant from taking Petersburg almost without

resistance.

|

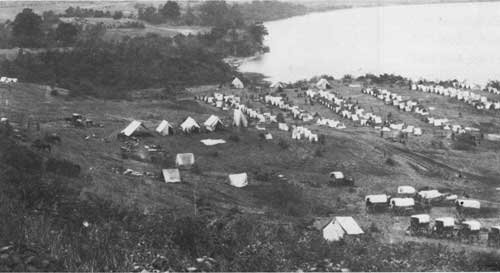

CAMP OF THE FIRST MASSACHUSETTS AND SECOND NEW YORK AT BELLE PLAIN ON

THE WAY TO PETERSBURG. (LC)

|

|

GENERAL JUBAL EARLY (CWL)

|

Lee hurriedly moved south when he realized what had happened and only

barely got into Petersburg's defenses before Grant struck again. He held

the Yankees at bay, but at the cost of what he had long feared. He could

move no more. Grant had him stuck in earthwork defenses that he could

not abandon without giving up Petersburg and Richmond itself. Lee's army

was exhausted. Almost half of it as casualties had been suffered in the

past weeks, and he had no replacements. Grant and Meade took over 50,000

casualties, and the soldiers who remained were bone weary and almost in

shock. But the Yankees could get more men, and now Grant accepted the

siege he had hoped to avert. From the end of June through the end of the

year and on into the spring of 1865 he gradually extended his lines,

pressing Lee ever closer. One by one he cut off the rail lines into

Richmond until only one remained, and from time to time he tried to end

the siege by breaking through, to no avail. But as Lee had said, time

now fought beside the Federals. The best he could do was to send General

Jubal Early and his corps on a daring raid through the Shenandoah and

into Maryland. Early actually got to the environs of Washington, where

President Lincoln came briefly under fire as he watched skirmishing

before Early was forced to retire. Later that summer Grant sent his

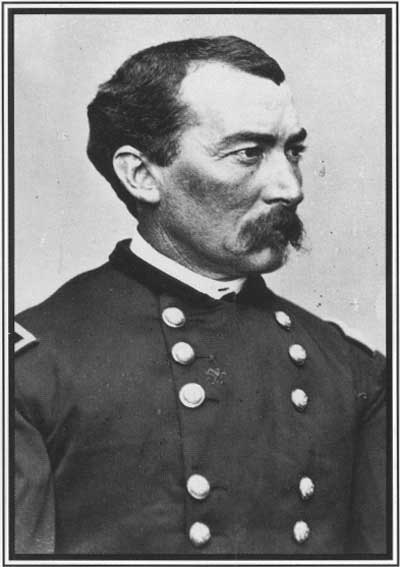

trusted henchman General Philip Sheridan to clean Early out of the

Valley, and in a series of battles in September and October Sheridan

essentially took Early out of the war, and with him the Shenandoah

itself. Meanwhile, out in the Trans-Mississippi, Confederates launched

their last major offensive of the war when General Sterling Price struck

north out of Arkansas in August and drove north into Missouri. He got

all the way to the Missouri River, near present-day Kansas City, before

Federal cavalry stopped him at Westport in the greatest battle fought in

that territory.

|

MAJOR GENERAL PHILIP SHERIDAN (LC)

|

|

GENERAL JOHN B. HOOD (CWL)

|

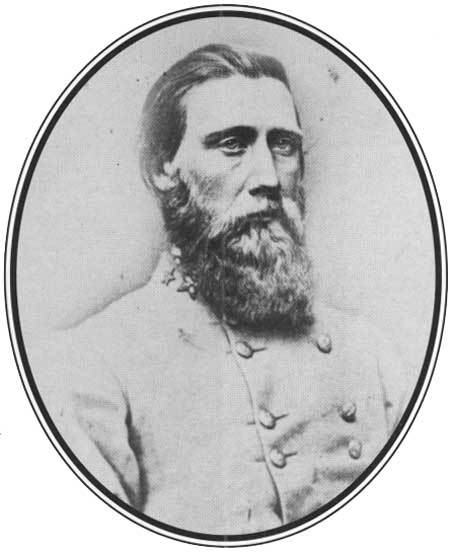

By this time Grant's great lieutenant Sherman enjoyed much more

spectacular success out in the West and much more room for maneuver, in

part because he faced a much lesser foe than Lee. Davis had no choice

but to replace Bragg after the rout at Missionary Ridge, but he had no

other commanders to equal his great Virginian. Despite his distrust of

Joseph E. Johnston, Davis was persuaded to turn to him in the hope that

he could hold north Georgia and keep Sherman from knocking at the door

to Atlanta. He hoped in vain. When the campaign began on May 7 with

Sherman's advance south, Johnston set the pattern for the campaign to

follow. With a very favorable defensive position on Rocky Face Ridge

near Dalton, Georgia, he neglected to guard a crucial gap that Sherman

penetrated, forcing Johnston to withdraw to avoid having his army cut in

two. Johnston pulled back without accepting a serious engagement and

next took up a line several miles south near Resaca. Hereafter Sherman

would advance, feint in Johnston's front, and then threaten to move

around his left flank, and the Confederate would withdraw without a

fight. Johnston pulled back to Cassville, and then again to Allatoona

Pass, and so on. Only at Kenesaw Mountain, on June 27, did Johnston

actually make a genuine stand, and there Sherman suffered a severe

repulse when—like Grant at Cold Harbor—he abandoned his own

policy and ordered a frontal assault up the steep slope against strong

enemy defenses.

|

SHERMAN'S SOLDIERS DESTROY RAILROAD TRACKS IN ATLANTA. (LC)

|

He need not have bothered, perhaps, for Johnston soon pulled back

again to the Chattahoochee River, a wonderful natural line of defense

that Sherman feinted him out of without difficulty. By now Jefferson

Davis in Richmond was almost frantic. Not only was Johnston in almost

constant retreat without giving battle, but he would not tell the

president what he intended to do. Finally convinced that Johnston would

abandon Atlanta itself without a fight, Davis relieved him on July 17

with General John B. Hood. Hood at least was a fighter, but his audacity

sometimes outweighed his good sense. Pushed back into the defenses of

the city after a sharp engagement at Peachtree Creek, Hood bravely tried

to save Atlanta by turning from hunted to hunter. He moved out of his

defenses to attack on July 22. Despite able planning, the effort failed,

and Sherman now spread out to do to Atlanta what Grant even then was

doing to Petersburg. For over a month Sherman laid siege to the city,

all the while extending his lines until they nearly encircled Hood.

Finally the Confederates had no choice but to evacuate on September 1 to

avoid being completely surrounded, and Atlanta fell at last. It was an

enormous morale boost to the Union, which was wearied by the high losses

in Virginia and the stagnant siege at Petersburg. Sherman's victory

played no small part in helping Lincoln achieve reelection, and that, in

turn, helped ensure the eventual outcome of the war.

|

"THE BATTLE OF NASHVILLE" PAINTED BY HOWARD PYLE IN 1907. (PHOTO BY GARY

MORTENSON, COURTESY OF MINNESOTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

|

SHERMAN'S PATH OF DESTRUCTION LED THROUGH SAVANNAH, GEORGIA. (LC)

|

This was not to be the last heard from Hood, however. Later that

fall, in an effort to regain Tennessee and force Sherman to abandon

Georgia, the Confederate drove north through Georgia and all the way to

the center of the Volunteer State. Rather than be turned from his

mission to go on to the Atlantic, however, and knowing that Hood led a

weakened army, Sherman did not follow. Instead, he ordered several army

corps under Major General George H. Thomas to deal with Hood. By late

November Hood had reached Franklin, Tennessee, where he encountered

General John Schofield and unsuccessfully attacked in a battle that saw

five Confederate generals killed, including the "Stonewall of the West,"

Patrick R. Cleburne. Meanwhile, Thomas was in Nashville seeing to the

city's defenses and laboriously readying himself to move against Hood,

who now moved up within sight of the city and took up a position. Too

weak to attack and too stubborn to retire, Hood glared at Thomas for

days until the Yankee general finally made his move, an assault that

routed and all but erased Hood's organization. In tatters, his army

retreated back toward northern Mississippi, where Hood asked to be

relieved of command.

Meanwhile, leaving Thomas and Schofield to deal with Hood, Sherman

pressed on toward the sea on November 15. Thirty-six days later he

marched into Savannah, having cut yet another slice across the

Confederacy, and left a path of industrial and agricultural waste in his

wake. Now he perched on the Atlantic, ready to march northward to strike

Lee from the rear while Grant faced him at Petersburg. Unquestionably

the Confederacy was on its knees.

With almost four years of increasingly brutal warfare behind them,

North and South faced greater costs than the loss of cities and

hilltops. They were ravaging a whole generation of men. By the dawn of

1865 more than half a million men had died, 200,000 or more of them in

battle and the rest from disease. The wounded totaled well over a

million, and for any man injured in a vital organ, death was almost

inevitable. Yet sometimes the living would maintain that survival was

almost worse than death.

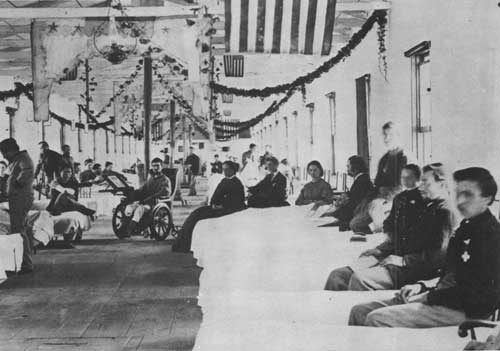

|

CARVER HOSPITAL IN WASHINGTON, SEPTEMBER, 1864 (LC)

|

Conditions in military hospitals on both sides could be appalling.

Medical and surgical knowledge had not progressed markedly for

generations. The only anesthesia available was opiates, chiefly

laudanum, that ran the risk of killing by an overdose or addiction if

taken over too long a period of recuperation, and chloroform, which

carried hazards of its own. Contrary to myth, almost all operations,

even in the hard-pressed South, were conducted with the patient under

some kind of sedative. Unfortunately, almost the only operation that

could be performed was bullet extraction. If the lead hit a bone in an

arm or leg, amputation almost always resulted, and then surgeons lost a

high percentage of patients from gangrene and other infections that

could set in afterward. Stonewall Jackson lost an arm as a result of his

mortal wound and was recovering from that nicely until pneumonia

attacked his weakened constitution. Thanks to utter ignorance about

asepsis and infection even minor wounds often led to death when treated

with contaminated instruments or handled by surgeons who went from

patient to patient without cleansing their hands, literally spreading

the infections they sought to prevent. Any form of internal surgery was

out of the question. Men with abdominal wounds were most often simply

left to heal or die on their own as the doctors turned their attention

to the less severe injuries that an amputation or some needle and thread

might help recover. For generations after the war, the empty sleeves and

trouser legs of aging veterans North and South paid mute testimony to

the ravages of bullets and surgery and the pain inflicted on mortal

flesh.

Disease proved to be an even greater killer. Except for those men who

had been city dwellers before the war, most of these men and boys had

never been exposed to large numbers of people before, and as a result

many never experienced even the minor childhood diseases like measles

and mumps, or the more severe scarlet fever and whooping cough. But in

camps with tens of thousands of men cramped together constantly, these

viruses raged through the regiments, and of course adults risk far

greater consequences from these diseases than children. Measles killed

almost as many as bullets in many units, and the surgeons were powerless

to help them.

|

SANITARY COMMISSION TENT AT GETTYSBURG, PA (USAMHI)

|

All that the doctors could do was try to make them comfortable. With

tens of thousands of casualties during and after the campaigns, some of

them taking years to recuperate, hospitals all across the nation bulged.

Cities like Nashville and Richmond, and even Washington, saw massive

tent cities arise on their outskirts. Inside the cities any available

warehouse or private dwelling could become a hospital, and on some

battlefields, as at Gettysburg, the wounded remained behind for months,

housed in tents as the doctors and nurses came to them. A host of

civilians volunteered to assist in relieving the suffering, and

charitable organizations such as the United States Sanitary Commission

raised funds to buy medicines and provide nurses. It seemed to many a

losing battle, a fight against unseen forces far more insidious than

mere cannon and bullets. Disease, infection, shock, and a host of other

enemies made no distinction between blue or gray. If a wound or the

measles did not kill the soldier, his other enemy could. From the time

of Fort Sumter, both sides dealt with the issue of prisoners of war,

never very adequately. No one at the outset envisioned the phenomenal

numbers of men who would be captured, whom the opposing side must

somehow care for. More than 150 prison camps operated during the

conflict, from small stations holding only a few hundred, to the massive

centers like Camp Sumter at Andersonville that housed almost 30,000. In

all during the war, at least 430,000 men, North and South, fell into

enemy hands, not counting the final surrenders. While about half of them

were paroled—released on their oath not to fight again—the

rest went to prisons that ranged from a simple city of tents in a field,

to old warehouses and factories, and even city jails.

Wherever a prisoner went, conditions were not good. In the North,

prison officials believed that a man in custody required less to eat

than an active soldier in the field. In the South the jailors simply did

not have enough to give them, and despite later claims that the

Confederacy deliberately starved Yankee prisoners, in fact the men ate

about as well as the Rebel soldiers themselves. Buildings were drafty,

often unheated and damp in winter, and hot in the summer. Confederates

kept at Johnson's Island on Lake Erie nearly froze to death. Yankees

kept at Camp Sumter and elsewhere suffered from fevers and malaria in

the heat and humidity. Occasionally prison guards did behave brutishly.

Occasionally fellow prisoners turned brutes themselves, bullying their

mates to claim precious food or fresh water. But mostly they all

suffered together. At Andersonville alone more than 12,000 perished, and

death rates ran almost as high in some Northern compounds like Fort

Delaware. At war's end many of the men released from these hell holes

looked more like skeletons than living humans, and the bitterness

engendered by prison suffering lasted longer than all of the other

animosities between Johnny Reb and Billy Yank.

|

BURYING THE DEAD AT ANDERSONVILLE, 1864 (USAMHI)

|

|

ELMIRA PRISON CAMP, ELMIRA, NY (LC)

|

|

|