|

|

PLOWSHARES INTO SWORDS

by William Marvel

The great smoke and clank of Northern factories credited an economy

different from, and in many ways hostile to that of the agrarian South.

|

Industry forged the forces that rent the country asunder in 1861. The

great smoke and clank of Northern factories created an economy different

from, and in many ways hostile to, that of the agrarian South, and the

underlying economic rivalries did as much to inflame the sections as the

emotional rhetoric over slavery. But industry also played a significant

role in welding the nation back together, for multitudes of Union troops

might not have won the war without Northern iron and steel.

Had anyone guessed the importance of railroads to the movement and

supply of armies, a rail map alone might have dampened Southern ardor.

The vast Confederacy contained less than half the track mileage found in

the loyal states, and much of its sparse network lay unconnected only

one fragile corridor linked the key cities of Richmond and Chattanooga,

and it was virtually impossible to reach the heart of the Confederacy by

rail from west of the Mississippi or the state of Florida. In the North,

a passenger could travel between almost any major cities with little

more than a change of cars.

The distribution of iron and steel works told an even more alarming

tale. In 1858 the vast majority of forges and foundries lay in

Pennsylvania, and most of the rest were found north of the Ohio and

Potomac Rivers. Of the twenty-two cities that employed more than 5,000

hands at manufacturing in 1859, only one, Richmond, was in the South;

Cincinnati and Chicago counted more than 25,000 operatives, while

Philadelphia boasted over 50,000. The greatest manufacturing center of

all was New York, with well over 100,000 employees. In the year before

the war began, the South's percentage of the national manufacturing

output still lagged in the single digits.

This industrial backwardness quickly caught up with the Confederacy.

Railroads soon began to suffer from insufficient spare parts for

locomotives and from a shortage of rail stock, for the South began the

war with too few machine shops and only one rolling mill. And when the

gray armies moved cross-country their wagons creaked precariously on

homemade repairs. Efforts to correct the deficiencies succeeded only

moderately and briefly, for Federal armies advanced to swallow new

factories as quickly as they could be constructed.

Even clothing grew scarce. With no textile production outside private

homes, the Confederate War Department began ordering shirts, socks,

uniform material, and shoes from abroad as early as the summer of 1861.

Shoes remained a prized commodity throughout the conflict: rumors of

shoes drew the Southern troops who began the battle of Gettysburg, and

the next winter Confederate generals gave their men patterns and

instructions for making their own moccasins. In the final year of the

war, Confederate quartermasters scoured their prison camps for Yankee

cobblers.

Weapons were the greatest embarrassment, however. From the outset,

Confederate troops found themselves outgunned. Southern forces captured

about 150,000 small arms when they closed in on U.S. armories in 1861,

but three times that many remained in the North. As each side geared up

for wartime production, the South only fell further behind.

By September of 1862 only 14,349 small arms had been manufactured in

the entire Confederacy, though public and private armories had been

established for the production of as many as 3,600 weapons monthly. That

capacity fell short of its promise, though, and by September of 1863

fewer than 35,000 more rifles, carbines, and revolvers had been

delivered. Southern production dropped to 20,000 for 1864, while just

one Northern facility, the National Armory in Springfield,

Massachusetts, was capable of manufacturing 300,000 rifles a year.

The Confederacy looked to foreign suppliers for firepower, and after

1861 most of its small arms came through the blockade. By the autumn of

1862 some 300,000 muskets and rifles had been issued to Confederate

troops, while Northern soldiers had drawn more than a million. Another

1,275,000 Federal small arms stood in various stages of completion by

November of 1862, and Northern armories lay largely idle by the end of

the war, for the U.S. Army held 750,000 rifles in storage, besides the

million and more still in the hands of its soldiers.

Artillery was more difficult to import, and much of the South's

heavier ordnance came from Richmond's Tredegar Iron Works. At full

production in the year ending with October of 1863, the South put a

total of 677 new cannon into the field from all sources, including

purchase. A year earlier, Northern foundries had already turned out

2,121 finished guns, and they had cast the tubes of 3,100 more.

By the final act in the drama, the slow-moving wheels of Southern

industry had ground to a complete halt. The Confederacy's last

manufacturing center went up in smoke the day the Army of Northern

Virginia evacuated Richmond, and none of the wagons or guns lost on that

final march could ever be replaced. Of the 28,000 ragged Confederates

who straggled in to Appomattox Court House for the surrender, barely one

in three still carried a rifle.

|

|

THE CITIZENS OF THE SOUTH SUFFERED INCREDIBLE HARDSHIPS DURING THE WAR.

(LC)

|

From the outset, the Confederates believed that much of their hope of

independence lay in persuading European powers, especially England and

France, to grant them diplomatic recognition followed by military

intervention. To persuade—or coerce—them into doing so, the

Confederates relied on "King Cotton." They would voluntarily withhold

sale and shipment of cotton to Europe's hungry textile mills, hoping

that nations would risk siding with them in order to reopen the trade.

Yet by the end of 1861 Davis and others realized that the policy would

not work. Britain already had a surplus of cotton on hand, and other

sources in India and Egypt were opening. Nations, like men, acted

chiefly out of self-interest, and Britain and France had nothing to gain

from going to war with the Union. Moreover, both felt uneasy about

slavery, having abandoned it themselves long before. Siding with the

Confederacy would not put them on the moral high ground. Toward the end

of the war, when Davis actually offered the prospect of

emancipation—which he had not the power to enforce—in return

for recognition, it came as too little and far too late.

|

PHOTOGRAPH OF UNION WEAPONS STOCKPILE. THE NORTH HAD THE ADVANTAGE OF A

STRONGER INDUSTRIAL BASE BEHIND ITS WAR EFFORT. (LC)

|

Part of Davis's success against his enemies within lay in the nature

of his people. The common folk of the Confederacy willingly sustained

incredible sacrifice during the first three years of the war. A

significantly higher proportion of its military-age men volunteered than

in the North, most of them motivated not by slavery—few were

slaveholders—or even by a sense of Confederate nationalism.

Overwhelmingly they enlisted to protect their homes and hearths from an

invader's heel. And whereas the North waged war while engaging in a host

of other domestic endeavors not related to the conflict, almost from the

first the South had to divert every muscle, every sinew, every fiber of

its body to the one task of defending itself. All industry converted to

war production. Civilians lived in some areas at subsistence levels in

order to get foodstuffs to the armies. Hundreds of thousands were

dislocated as refugees by the moving armies and swarmed to the cities to

work in factories or hospitals or simply to try to survive. Beautiful

iron railings and church bells were turned into cannon, wedding dresses

became battle flags, and gold and jewelry were exchanged for cash to buy

weapons and munitions from abroad. Only in 1864 did the exhaustion from

this incredible exertion finally begin to tell in increasing desertions

from the army, in a mounting war resistance among the largely Unionist

peoples of the Appalachian hill country, and in a growing resignation

among even the most patriotic that they had done all they could and that

it would not be enough. As 1865 dawned, even if the Confederate armies

had enjoyed enough manpower to fight with a hope of victory—which

they did not—they no longer had a potent civilian and industrial

phalanx behind them. Too much lay destroyed, too many were dead.

A harbinger of the direction the war would take came just two days

after Davis received that telegram from Bragg announcing his victory at

Stones River. From what looked like certain triumph on December 31, the

conflict went against the Confederates in more fighting that followed,

and in the end Bragg had to abandon the field. Stones River now loomed

as a Yankee victory, though marginal. Moreover, it only presaged what

was to follow in the West. Bragg's army fell into some demoralization

after being led by him in two successive defeats and retreats, and

internal squabbling broke out in his high command that would last for

the rest of the year. In fact, he would not lead the Army of Tennessee

in battle again for over eight months as he battled with his own

commanders and dithered over what course to adopt in the field.

Meanwhile, the war went on around him.

|

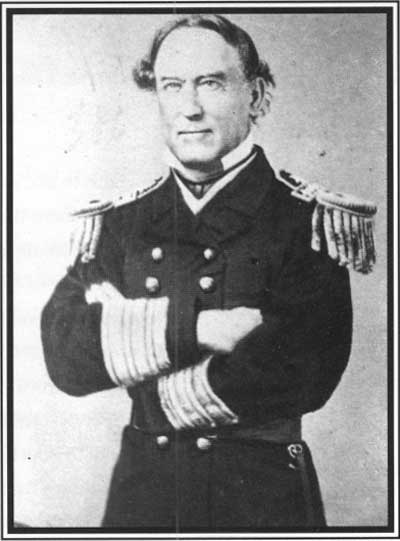

ADMIRAL DAVID DIXON PORTER (USAMHI)

|

|

MAJOR GENERAL JOHN C. PEMBERTON (USAMHI)

|

U. S. Grant, now a major general thanks to his successes in 1862,

never gave up his intention to take Vicksburg on the Mississippi,

despite a series of reverses the year before. Throughout the winter and

on into the spring he steadily planned and maneuvered. During April he

moved much of his army down the river, then landed it on the opposite

bank of the river and started the laborious process of moving it south

through the swamps and bayous of Arkansas, until it emerged once more on

the riverbank several miles below Vicksburg. Then in a daring maneuver,

Captain David Dixon Porter ran his fleet of gunboats, troop transports,

and barges south by night, right past the looming batteries on the

bluffs around Vicksburg. Although discovered, they kept on, and in the

end all but one gunboat and seven transports made it safely past.

Rendezvousing with Grant downstream, they ferried his army across to the

east bank, and the Yankees started advancing north, now deep in the

enemy rear and threatening to take Vicksburg from its land side.

Grant's operations left the Confederate defender, General John C.

Pemberton, only two alternatives. Either he moved out of Vicksburg to

try to defeat Grant in the open field, or he waited in his defenses,

where inevitably the Federals would surround him and lay siege.

Pemberton chose to take a risk and marched out. On May 16, 1863, after

Grant had already brushed aside some smaller Rebel forces at Jackson, he

engaged Pemberton at Champion's Hill and defeated him, sending some of

the Confederate army scurrying off to the south and the rest back to

Vicksburg. Three days later Grant stood at Vicksburg's gates. His

initial attacks failed to break through, and he decided to erect siege

works instead. For 47 days Vicksburg held out. Nothing could get into or

out of the city. Soldiers and civilians alike were reduced to eating

horses and mules, even rats. Pemberton expected a relief force commanded

by Joseph E. Johnston—now recovered from his wound—to come to

his aid, but Johnston was as irresolute as ever and simply watched from

a distance as Pemberton's force withered. Finally, unable to break out

and unable to hold out, Pemberton surrendered on July 4, giving the

Union a resounding victory for its Independence Day. A few days later

the other Rebel river bastion at Port Hudson, Louisiana, fell after a

siege. Now at last, the Union controlled the entire length of the

Mississippi, and the Confederacy was split in twain.

|

THE FOURTH MINNESOTA REGIMENT ENTERING VICKSBURG (PAINTING BY FRANCES

MILLET. COURTESY OF MINNESOTA HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

|

MAJOR GENERAL JOSEPH HOOKER (USAMHI)

|

In the East, after what appeared to be yet another repeat of the

Confederate successes of previous years, Southern fortunes took a

drastic downturn as well. Lincoln had little choice but to replace

Burnside after Fredericksburg, and the new commander seemed to inspire

his men almost as much as McClellan had. Major General Joseph Hooker had

been one of the Army of the Potomac's most combative corps commanders

and he actively politicked to get the command. Lincoln gave it to him,

and Hooker launched an excellent campaign in the spring to make one more

drive toward Richmond. At first, he seemingly took Lee unawares and got

his army across the Rappahannock before Lee was ready for him. But then

the audacious Lee, outnumbered more than two to one, turned and marched

to attack Hooker, which so unnerved the Federal that he stopped and

dithered. That was all the opening Lee needed. As he occupied Hooker's

attention in his front, he discovered that Hooker's right flank lay

exposed and unprotected. Early on May 2 Stonewall Jackson led most of

the army in a hard march some sixteen miles around the Yankee right and

in the late afternoon emerged unsuspected on Hooker's flank and rear and

put almost half of the Union army to rout. In the process, Jackson's own

men accidentally gave him a mortal wound. Lee's cavalry chieftain,

General J. E. B. Stuart, took over Jackson's command and the next day

continued to push the Yankees back until Hooker lost his fight

altogether and withdrew back across the Rappahannock.

|

MEMBERS OF THE 24TH MICHIGAN INFANTRY LIE DEAD AFTER FIGHTING AT

GETTYSBURG. (LC)

|

|

MAJ. GEN. J.E.B. STUART (USAMHI)

|

The startling victory came at a high price with the death of Jackson,

but Lee saw a whole summer of campaigning weather ahead of him and knew

that he could not let his army lie idle. Having the initiative, he must

keep it. In June he launched another invasion of the North, this time

driving across Maryland and into Pennsylvania, very nearly to the

capital of Harrisburg. The movement panicked the North, Washington

feared for its safety, and Lincoln, lacking confidence in Hooker,

replaced him on June 28 with General George G. Meade, Less than 72 hours

later Meade would be locked in the greatest battle ever fought on the

continent.

|

MAJOR GENERAL GEORGE G. MEADE (USAMHI)

|

Hurrying to catch up to Lee and get his own army between the

Confederates and Washington, Meade finally stopped him in central

Pennsylvania. Their advance units encountered each other at Gettysburg

on July 1. It all went against the Yankees on that first day, and by

evening they had fallen back to some high ground just south of town.

Hurriedly both commanders rushed more troops to the battlefield during

the night, and on July 2 the fighting renewed. A host of places became

immortal. The Wheat Field. The Peach Orchard. Devil's Den. Little Round

Top. Culp's Hill. Lee took the offensive throughout the day, but no

matter where he struck, the Federals either held their ground or else

pulled back to better defenses. The climax came the following day.

Having tried the left and right flanks of the enemy line, Lee launched a

massive assault against the center. Two whole divisions and portions of

others massed for what came to be called Pickett's Charge. Across almost

a mile of open ground the Confederates marched, then rushed up against

the guns and infantry on the Union line. Briefly a few broke through

before Federal firepower and valor drove them back with appalling

casualties. Lee had nothing left. His army was battered and

disorganized, and he had no choice but to retreat back to Virginia.

Coming as it did the day before the surrender of Vicksburg, the

victory at Gettysburg supercharged the North and cast a pall over

Southerners. Yet the battle severely damaged Meade, too. His army would

not be in shape to fight another battle for months, while Lee took such

heavy losses in men and commanders that the Army of Northern Virginia

would never be the same again. For the balance of the year, both Meade

and Lee did little more than feint and maneuver as they sought to

recover from Gettysburg.

Out in the West, however, Bragg finally showed some activity. He and

Rosecrans traded possession of Chattanooga in August and September and

then set out in a stumbling way, each hoping to drive the other out of

southeastern Tennessee. On September 19, after considerable earlier

skirmishing, they met along Chickamauga Creek a few miles south of

Chattanooga. Neither commander knew enough of the confusing terrain to

control his own army, much less know what his opponent was about and

Bragg especially suffered with balky corps commanders who ignored or

delayed in obeying his orders. As a result, the first day's fight was

indecisive. But during the night a massive reinforcement from Virginia,

led by Lee's premier corps commander, James Longstreet, arrived to

bolster Bragg. The next day Bragg launched his main attack and so

managed to harry Rosecrans's left flank that repeated pleas for

reinforcement led to a confusion in the Federal center, resulting in a

division moving off to support the left and leaving a huge gap in the

line just as Longstreet launched an attack. He split the Army of the

Cumberland in two. Rosecrans and many of his generals fled back to

Chattanooga, and only the spirited resistance of George H. Thomas and

those remaining kept the rout from becoming a disaster. It would be the

Confederacy's greatest victory in the West.

Unfortunately, Bragg followed it with the most humiliating defeat.

When the Federals retreated to Chattanooga, Bragg besieged them by

placing his army on the heights of Missionary Ridge and Lookout

Mountain, effectively boxing Rosecrans in with his back to the Tennessee

River. Soon Lincoln put Thomas in charge in Rosecrans's place and

ordered Grant to come to Chattanooga to retrieve the situation. On

November 24, after breaking the siege and resupplying and reorganizing

the army, Grant attacked and took Lookout Mountain. The next day Thomas

ordered his army to move against Missionary Ridge. Going beyond their

orders, the bluecoats drove straight up its slopes and completely routed

Bragg's army, sending it fleeing in disorganization into north Georgia.

As 1863 closed, well might people North and South wonder at what a

difference a year could make.

|

PHOTOGRAPH OF CAPTURED CONFEDERATE CANNON AFTER THE BATTLE OF

CHATTANOOGA. (USAMHI)

|

There was another theater of the war in which Union fortunes now

looked good, one not bounded by mountains or dotted with cities. From

the very first, both sides knew that this conflict would be fought on

the water as well as the land. Neither came prepared. Lincoln's entire

fleet amounted to no more than a dozen modern warships well outfitted in

1861. Several were scuttled in Southern ports when the Union navy

abandoned them to Confederates, and others were far away on distant

seas. Yet with this small nucleus Lincoln declared a blockade of

Confederate ports on April 16, 1861, and ordered his few ships to post

themselves off Charleston, Wilmington, and the other major harbors into

which foreign shipping could bring arms and munitions. By the summer, as

Lincoln pressed obsolete warships, New York ferry boats, and even

private luxury yachts into service, the blockade began to have some

small effect, and every month thereafter it became tighter and stronger.

Only about 10 percent of the ships that attempted to run the blockade in

1861 fell prey to Yankee blockaders, but by 1864, when a total of 600 or

more vessels patrolled the Confederate coast and its harbors, one of

every three blockade runners never got through. Pinning so much of its

hopes on outside support and materials that it could not manufacture for

itself, the Confederacy encouraged private entrepreneurs to build fast,

sleek vessels that could get in and out of port through the cordon of

enemy ships. Some runners made considerable fortunes, and even a single

successful run with a full cargo of guns or powder, not to mention

civilian luxuries, could make a captain a wealthy man and pay for the

vessel as well.

|

LIEUTENANT GENERAL JAMES LONGSTREET (USAMHI)

|

|

ENGRAVING FROM HARPER'S WEEKLY DEPICTS THOMAS'S MEN REPULSING THE

CONFEDERATE CHARGE AT THE BATTLE OF CHICKAMAUGA. (LC)

|

By contrast, the Confederacy started with nothing. Its first navy

consisted only of the few ships it captured at the outset. Immediately

Secretary of the Navy Stephen R. Mallory started a program of buying

ships abroad and converting them for war service. He also perceived the

potential of ironclad warships, as yet untried in America. At Hampton

Roads, Virginia, he raised the hulk of the Federal frigate

Merrimack and had it rebuilt and converted, covered with a long

barnlike shed with sloping sides covered with heavy iron plating, and

renamed it the Virginia. On March 8, 1862, it steamed out into

the Roads and challenged the Union blockaders, almost destroying the

wooden fleet single-handedly. But when it went back the next day to

finish the job, it encountered the Yankees own ironclad, the little

Monitor. Better designed, better built, and a much smaller

target, the Monitor steamed circles around the Virginia.

At the end of the day both vessels retired, each thinking the other had

given up, but the real victory lay with the Monitor, for the

Virginia never steamed into the Roads again to threaten the Union

fleet.

|

THE BROOKLYN, NY NAVY YARD, 1861

|

|

THE MONITOR ATTACKS A CONFEDERATE WAR VESSEL IN THIS ILLUSTRATION FROM

SHEET MUSIC OF THE TIME. (LC)

|

|

ADMIRAL DAVID G. FARRAGUT (CWL)

|

Seeing what these vessels accomplished started a virtual ironclad

fever North and South. Dozens would be constructed during the remainder

of the war. Most Confederate ships followed roughly the pattern of the

Virginia, and most suffered its weaknesses of faulty engines and

makeshift construction. The Union used a variety of designs, including

behemoth ships that plied the Mississippi and its tributaries.

Ironclads, and the lesser gunboats that sailed with them, rarely met in

actual combat with each other, but where they did on the Mississippi,

the Confederates almost invariably found themselves out-gunned and

facing better armor. Still, the exploits of a few gallant ships like the

Arkansas and the Tennessee showed that valor and

determination could make up for what these Rebel ironclads lacked in

armament and iron.

On the high seas, the Confederates early decided to take the

offensive by attempting to disrupt Union commerce. Sinking Yankee

merchant vessels, Davis reasoned, would discourage foreign shippers from

risking their cargoes to Northern ships and at the same time show Union

civilians that they were not immune to the war's hazards. Hit the enemy

in the pocketbook, Confederates thought, and they would quit quickly,

for the average Confederate believed erroneously that the Yankee valued

his money above all else. Powerful vessels like the Sumter, the

Florida, the Shenandoah, and most of all the

Alabama, spread terror among Yankee captains, especially when

commanded by daring and ruthless men like Admiral Raphael Semmes. In the

end, however, their impact on the Northern war effort was minimal. Most

were hunted down and sunk, and their greatest impact on the war was the

international turmoil they caused between the Union and England, where

many of them were built or fitted out.

By the dawn of 1865, the Confederacy had almost no navy left. As each

of its major ports fell, one after another, to Union gunboats, the ships

defending them were either lost or, having nowhere to go, steamed up

rivers to the interior, where they posed no threat at all and were

usually scuttled by their own crews. Some of the fighting for these

ports was dramatic, nowhere more so than at Charleston in 1863, when it

was demonstrated that ironclads did have limitations as a fleet of

Yankee ironclads tried unsuccessfully to attack Fort Sumter and only got

terrible losses for its pains. On the other hand, at Mobile Bay on

August 5, 1864, the daring Farragut demonstrated, as he had on the

Mississippi, that ironclads could simply ignore forts and steam right on

past to do battle with enemy vessels. Braving the fire of two masonry

forts on either side, he ran his fleet past them and then took the bay

itself and the Confederate ships in it, even while the Rebels still held

the forts at the bay's mouth. Inevitably, they later had to surrender.

Farragut also immortalized himself by his determination to "damn the

torpedoes," when he was told that the Confederates had placed underwater

mines called torpedoes in the main channel. One of his ironclads, the

Tecumseh, struck one and went to the bottom in seconds, but

Farragut pressed on undeterred.

|

|