|

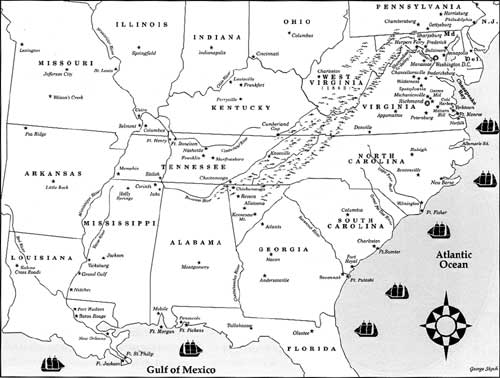

BATTLES

by William Marvel

Below are twenty-five of the most important land battles of the Civil

War. Although the bloodiest encounters are included here, some of those

that bore the greatest strategic or political fruits were relatively

small affairs. All figures for the numbers of troops involved are

approximate, as well as arguable. Casualty figures represent killed,

wounded, and missing, and many are estimates, especially on the

Confederate side.

1. MANASSAS, VIRGINIA, JULY 21, 1861. Union forces 32,000, casualties

2,708; Confederate forces 35,000, casualties 1,982. Also known as First

Bull Run, this tactical Confederate victory left Southerners

overconfident and stiffened Northern resolution.

2. WILSON'S CREEK, MISSOURI, AUGUST 10, 1861. Union forces 5,400,

casualties 1,235; Confederate forces 12,000, casualties 1,184. Another

tactical victory for the South, this engagement almost stopped

Confederate momentum in a key border state.

3. GLORIETA, NEW MEXICO, MARCH 28, 1862. Union forces 1,300;

Confederate forces 700; casualties just over 100 on each side. This

desperate skirmish saved the Far West for the Union.

4. SHILOH, TENNESSEE, APRIL 6-7, 1862. Union forces 60,000,

casualties 13,000; Confederate forces 40,000, casualties 10,700. Here

the Confederacy missed an opportunity to destroy the major Federal army

in the western theater.

5. SEVEN DAYS' BATTLES, VIRGINIA, JUNE 25-JULY 1, 1862. Union forces

100,000, casualties 15,849; Confederate forces 90,000, casualties

20,614. This series of battles drove the principal Union army away from

the Confederate capital.

6. MANASSAS, VIRGINIA, AUGUST 29-30, 1862. Union forces 60,000,

casualties 13,783; Confederate forces 50,000, casualties 8,681. In this,

the second battle of Bull Run, Robert E. Lee's Confederates routed the

second prong of the Federal effort against Richmond.

McClellan failed to destroy Lees isolated and weakened army, but

he stopped the first invasion of the North and allowed President Lincoln

to issue the Emancipation Proclamation.

|

7. ANTIETAM, MARYLAND, SEPTEMBER 17, 1862. Union forces 80,000,

casualties 12,410; Confederate forces 40,000, casualties 10,318. In a

battle known to the South as Sharpsburg, George McClellan failed to

destroy Lee's isolated and weakened army, but he stopped the first

invasion of the North and allowed President Lincoln to issue the

Emancipation Proclamation.

8. PERRYVILLE, KENTUCKY, OCTOBER 8, 1862. Union forces 37,000,

casualties 4,211; Confederate forces 16,000, casualties 3,396. This

fierce little battle ended the Confederate invasion of Kentucky.

9. FREDERICKSBURG, VIRGINIA, DECEMBER 11-15, 1862. Union forces

105,000, casualties 12,653; Confederate forces 80,000, casualties (est.)

5,000. Two assaults on either end of Lee's army both failed with heavy

Union losses, and the defeat severely affected Northern morale.

10. STONES RIVER, TENNESSEE, DECEMBER 31, 1862-JANUARY 2, 1863. Union

forces 44,000, casualties 12,906; Confederate forces 38,000, casualties

11,740. The repulse of this Confederate attack helped to improve the

North's flagging will to fight.

11. CHANCELLORSVILLE, VIRGINIA, MAY 2-4, 1863. Union forces 90,000,

casualties 16,792; Confederate forces 45,000, casualties 12,754. This

classic defeat of the advancing Federal army paved the way for another

invasion of the North.

12. GETTYSBURG, JULY 1-3, 1863. Union forces 90,000, casualties

23,190; Confederate forces 76,000, casualties 27,899. Here the Union

Army of the Potomac won its first real victory over Lee's Confederates,

ending the deepest invasion of Northern territory, but once again the

crippled Southern army escaped back into Virginia.

13. SIEGE OF VICKSBURG, MISSISSIPPI, MAY 19-JULY 4, 1863. Union

forces 45,000, casualties 8,765; Confederate forces 32,000, casualties

32,000 (mostly prisoners). The capture of an entire Confederate army

spread gloom through the South and opened the Mississippi River to

Federal navigation, splitting the Confederacy in two.

14. CHICKAMAUGA, GEORGIA, SEPTEMBER 19-20, 1863. Union forces 58,000,

casualties 16,179; Confederate forces 66,000, casualties 18,454. A rare

concentration of superior Confederate forces drove the Union Army of the

Tennessee out of Georgia and bottled it up in Chattanooga.

15. CHATTANOOGA, NOVEMBER 24-25, 1863. Union forces 61,000,

casualties 5,824; Confederate forces 44,000, casualties 6,667. Ulysses

Grant broke the siege of Chattanooga and sent the Confederates fleeing

back into northern Georgia.

16. ATLANTA, GEORGIA, CAMPAIGN, MAY 6-SEPTEMBER 2, 1864. Union forces

99,000, casualties 35,000; Confederate forces 60,000, casualties (est.)

30,000. The capture of this important manufacturing and communications

center helped President Lincoln win reelection.

17. WILDERNESS, VIRGINIA, MAY 5-6, 1864. Union forces 119,000,

casualties 17,666; Confederate forces 65,000, casualties (est.) 11,000.

Lee interrupted Grant's determined offensive but did not stop it despite

furious resistance.

18. SPOTSYLVANIA, VIRGINIA, MAY 9-21, 1864. Union forces 105,000,

casualties 18,399; Confederate forces 54,000, casualties (est.) 10,000.

Again Lee stalled Grant, inflicting severe casualties but suffering

commensurate losses.

Here Lee diverted Grant from Richmond one more time, stunning the

Union army and discouraging it from attacking entrenchments.

|

19. COLD HARBOR, VIRGINIA, JUNE 2-4, 1864. Union forces 100,000,

casualties 7,000; Confederate forces 58,000, casualties (est.) 1,500.

Here Lee diverted Grant from Richmond one more time, stunning the Union

army and discouraging it from attacking entrenchments.

20. SIEGE OF PETERSBURG AND RICHMOND, VIRGINIA, JUNE 15, 1864-APRIL

2, 1865. Union forces 104,000 (monthly average), casualties 55,000;

Confederate forces 63,000 (average), casualties (est.) 30,000. While the

Confederate army prolonged the war by holding out so long, the outcome

was virtually assured from the moment the siege began.

21. CEDAR CREEK, VIRGINIA, OCTOBER 19, 1864. Union forces 40,000,

casualties 5,665; Confederate forces 18,000, casualties (est.) 2,600.

What began as a Federal rout turned into a spectacular victory that

ended effective Confederate resistance in the Shenandoah Valley.

22. NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE, DECEMBER 15-16, 1864. Union forces 50,000,

casualties 3,061; Confederate forces 30,000; casualties (est.) 6,000.

The Confederate Army of Tennessee was driven from the field and all but

destroyed by a Federal counterattack.

23. SAVANNAH CAMPAIGN, NOVEMBER 15-DECEMBER 22, 1864. Union forces

65,000, casualties 1338; Confederate forces 12,000, casualties (est.)

600. William Sherman cut a broad swath across Georgia in his March to

the Sea, depleting civilian resources and morale while hopelessly

outnumbered Confederates offered faint resistance.

24. BENTONVILLE, NORTH CAROLINA, MARCH 19-21, 1865. Union forces

48,000, casualties 1,527; Confederate forces 18,000, casualties (est.)

2,300. Accumulated fragments of the Confederacy's western and southern

armies made one last bold attack on Sherman's advancing host, but

overpowering Federal reinforcements forced a retreat.

25. APPOMATTOX, VIRGINIA, APRIL 8-9, 1865. Union forces 80,000,

casualties (est.) 300; Confederate forces 30,000, casualties 30,000

(mostly prisoners). With the surrender here of its most powerful and

prestigious army, the Confederacy's doom was assured.

|

(click on image for a PDF version)

(George Skoch)

|

|