|

THE BATTLE OF CHICKAMAUGA

Of all of the armies that fought in the American Civil War, none

struggled in more scenic or more rugged territory than did the Federal

Army of the Cumberland and the Confederate Army of Tennessee. Second

only in size to their counterparts in the eastern theater, these two

armies contended for mastery of the vast area encompassing eastern

Tennessee and northern Georgia and Alabama. Separated from their

respective capitals by the Appalachian Mountains, the armies shared many

characteristics. Both were almost exclusively composed of Americans from

the trans-Appalachian region. Both quickly learned that the region's

formidable rivers and mountain ranges tended to hinder rather than

facilitate offensive movements. Both armies found logistical sustainment

difficult in the sparsely settled region, and both depended upon fragile

single-track railroads for their lifeblood. All of these difficulties

were compounded by the inability of the armies' commanders to make their

needs adequately understood in Washington and Richmond. Thus the Army of

the Cumberland and the Army of Tennessee labored in relative obscurity.

Nevertheless, their struggle was critical to the outcome of the Civil

War.

The arena in which the two armies maneuvered was diverse in

topography yet rich in resources and strategic potential. Beginning in

the rolling farmland around Nashville, Tennessee, the theater stretched

east and south toward the foothills, then the main ridges of the

Appalachian Mountains. Coursing southwestward through these mountains

was the broad Tennessee River, which reached northeastern Alabama before

breaching the mountain wall on its way to the Ohio. Nestled on the south

bank of the river in the midst of the mountains was the city of

Chattanooga, Tennessee, home to some 2,500 people and a growing

commercial center. The river brought some of this commerce to

Chattanooga, but the city's primary link to the outside world was the

railroad. Four major rail lines entered the city, connecting it with

Memphis, Nashville, Richmond, and Atlanta. These railroads both enriched

Chattanooga and made it a military objective.

|

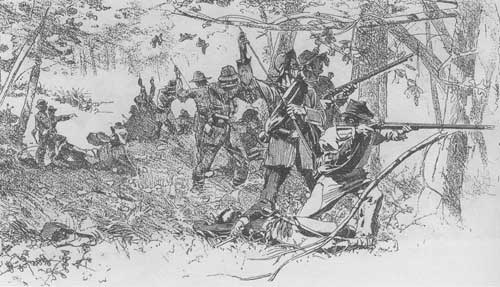

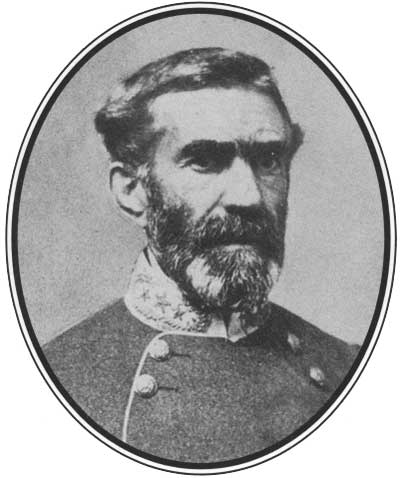

CONFEDERATE BATTLE LINE IN THE WOODS OF CHICKAMAUGA. (BL)

|

Several factors made retention of the region a matter of the greatest

importance to the Confederacy. First, the resources found within it were

vital to the new nation's war-making potential. The fertile land

southeast of Nashville provided great quantities of food and animals to

sustain the basic needs of the Army of Tennessee. In the mountains

themselves, numerous caves provided significant amounts of niter, a

critical ingredient in gunpowder. Similarly, mines in the vicinity of

Ducktown, Tennessee, produced 90 percent of the Confederacy's copper,

raw material for percussion caps and artillery projectiles. Second, in

strategic terms the region served as a shield protecting the

Confederacy's industrial and agricultural heartland in Alabama and

Georgia. Taken together, the multiple mountain ranges and the Tennessee

River represented a series of physical obstacles that, if used

intelligently, could deny enemy access to the Confederacy's vitals for

years, if not forever.

For the Union, too, this theater of war was critical to national

success. Because southeastern Tennessee provided food, fodder, and

animals to sustain the Army of Tennessee, the Union needed to deny it to

the Confederacy. Because the mineral resources of the southern mountains

contributed mightily to the Confederate war effort, those resources had

to be wrested from Richmond's grasp as soon as possible. If the

heartland of the Confederacy was ever to be pierced, the combined

barrier of Tennessee River and Appalachian Mountains had to be breached.

Finally, and this reason loomed large in the thinking of Abraham

Lincoln's government, thousands of citizens in eastern Tennessee

northern Georgia, and northeastern Alabama remained loyal to the Union

and suffered persecution for that loyalty. Thus the North desired to

regain control of the region to reduce the Confederacy's war-making

capacity, to facilitate further conquests, and to free masses of people

believed to be held against their will.

|

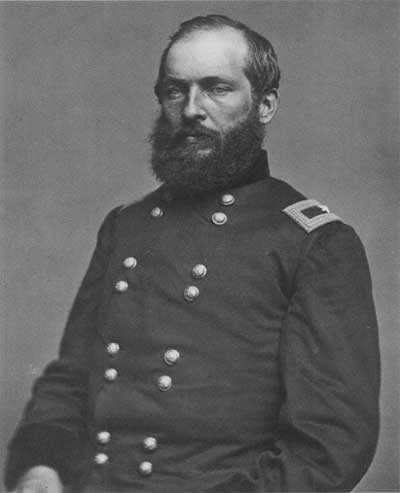

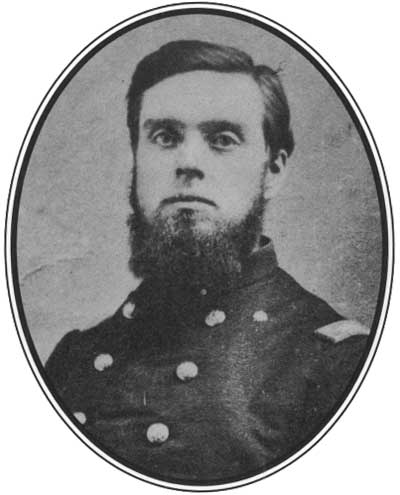

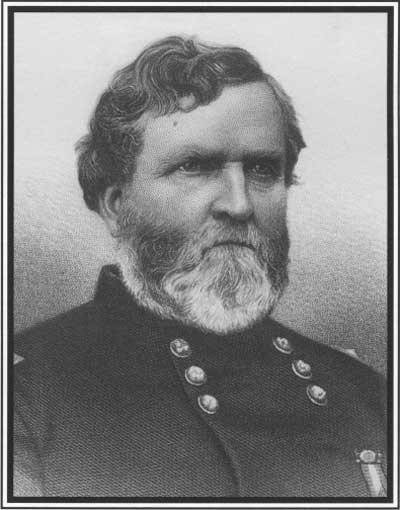

MAJOR GENERAL WILLIAM STARKE ROSECRANS (BL)

|

The Union's objectives for military operations in southeastern

Tennessee were articulated as early as October 24, 1862, when Major

General William Starke Rosecrans replaced Major General Don Carlos Buell

as commander of the new Department of the Cumberland. Rosecrans's

instructions from General in Chief Henry Halleck were: "First, to drive

the enemy from Kentucky and Middle Tennessee; second, to take and hold

East Tennessee, cutting the line of railroad at Chattanooga, Cleveland,

or Athens, so as to destroy the connection of the valley of Virginia

with Georgia and the other Southern States." The Lincoln administration

hoped that Rosecrans could make significant progress before the end of

1862, but it recognized that the road to Chattanooga would be long and

difficult. In response to the government's directive, Rosecrans in late

December began an offensive movement southeast of Nashville. That

advance culminated in a bloody fight at Stones River near Murfreesboro,

Tennessee. By the end of the battle on January 3, 1863, the Army of

Tennessee was in retreat.

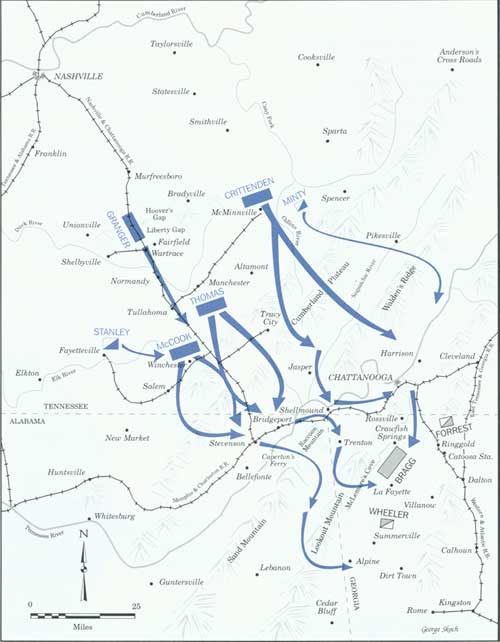

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

AUGUST 16 TO SEPTEMBER 12, 1863

By mid August, Rosecrans was ready to move from middle Tennessee. His

plan called for one corps to feint north of Chattanooga while three

others crossed the Tennessee River to the west and south, crossed the

Sand and Lookout Mountain ranges, and threatened Bragg's railroad supply

line southward. Rosecrans hoped this would trap Bragg or cause him to

abandon Chattanooga and retreat into Georgia.

Rosecrans's army began crossing the Cumberland Plateau on August 16

and moved to the river. On August 29, Thomas's, McCook's, and Stanley's

corps crossed the river near Stevenson, Bridgeport, and Shellmound. In

early September, they moved over the mountains twenty and forty miles

south of Chattanooga. Learning of the threat to his rear, Bragg

abandoned Chattanooga on September 8. The next day, Federals occupied

the city.

As Bragg retreated through LaFayette, he learned of the dispersion of

Rosecrans's force and turned to attack in McLemore's Cove. Command

dissension made the effort unsuccessful. Rosecrans then began to

consolidate his army.

|

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL JAMES ABRAM GARFIELD (LC)

|

The victory at Stones River made Rosecrans famous. Born in Ohio in

1819, he was an 1842 graduate of the United States Military Academy,

ranking fifth in a class of fifty-six. Finding promotion slow in the

peacetime army and having no opportunity to gain laurels in the

Mexican-American War, Rosecrans had resigned his commission in 1854.

Life as a businessman/inventor provided little more satisfaction and

nearly killed him when a failed experiment severely burned his face.

When the Civil War offered Rosecrans an opportunity to return to the

military profession, he seized it eagerly, rising to brigadier general

by the summer of 1861. Success in western Virginia soon brought transfer

to the West, where he gained a semi-independent command under Ulysses

Grant. In northern Mississippi Rosecrans fought strongly at the battles

of Iuka and Corinth, although he incurred Grant's enmity at the same

time. Promoted to major general in September 1862, he lobbied

successfully to have the commission backdated to March. Now he commanded

one of the nation's three largest field armies.

Even Rosecran's enemies agreed he was intellectually brilliant,

articulate in speech, firm in his convictions, and physically

courageous. He was also a man of prodigious energy, who drove both

himself and his subordinates unmercifully.

|

Even Rosecrans's enemies agreed he was intellectually brilliant,

articulate in speech, firm in his convictions, and physically

courageous. He was also a man of prodigious energy, who drove both

himself and his subordinates unmercifully. A devout Roman Catholic, he

retained a personal chaplain on his staff. Unfortunately, these

favorable characteristics were balanced by others less beneficial. In

temperament Rosecrans tended to be nervous and excitable. He was often

impatient and critical of others, especially his superiors, being "short

of temper and long of tongue." Neither introspective nor an astute judge

of others, Rosecrans was remarkably simple of outlook. Once convinced

of the correctness of his views, he was self-righteous in the extreme.

Generally affable with his staff, he often immersed himself in details

better left to subordinates. This tendency, coupled with his love of

philosophical discussion, led him to remain active well past midnight.

Unable to sleep late on campaign, but unwilling to modify his nocturnal

habits, Rosecrans became increasingly nervous and irascible as the

tempo of operations accelerated.

Immediately after his victory at Stones River Rosecrans began to

rebuild his army. In that battle the army had lost more than 13,000 men

and expended large quantities of supplies and equipment. Before any

further advance, those losses had to be restored. In addition,

casualties among senior leaders necessitated the integration of

replacements into the command structure. Rosecrans's own chief of staff,

Julius Garesche, had been killed at his side, a void that would be only

partially filled by the arrival of Brigadier General James Garfield as

Garesche's successor. In addition, the army's cavalry force required

massive expansion. Further, if the army were to advance beyond the

fertile fields of Middle Tennessee, enormous quantities of supplies had

to be accumulated at Nashville and Murfreesboro. Finally, the army's

movements must be coordinated with those of Major General Ambrose

Burnside's Army of the Ohio to the northeast and Major General Ulysses

Grant's Army of the Tennessee to the west. Despite a stream of

complaints from the Lincoln administration, Rosecrans refused to be

hurried.

|

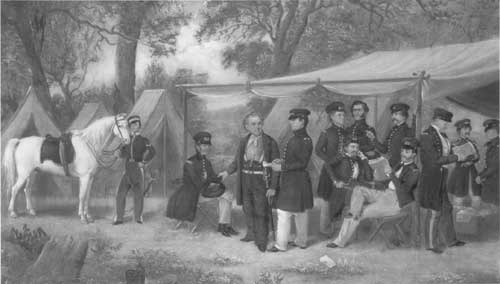

PAINTING OF ZACHARY TAYLOR'S HEADQUARTERS NEAR MONTERREY, MEXICO, 1847.

CAPTAIN BRAXTON BRAGG IS STANDING IN THE REAR WITHOUT A HAT. (COURTESY

OF SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION)

|

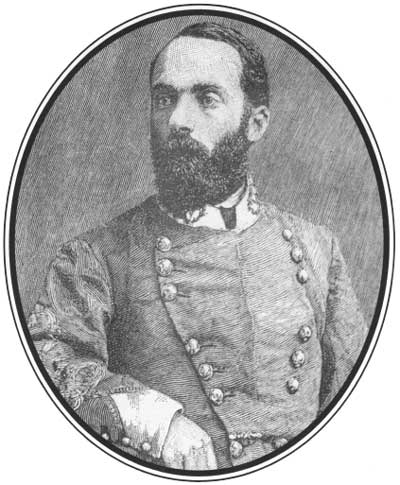

Facing Rosecrans's army was its old nemesis from Perryville and

Stones River, the Army of Tennessee, commanded by General Braxton Bragg.

Born in North Carolina in 1817, Bragg too was a product of the United

States Military Academy, graduating fifth in the class of 1837. Unlike

Rosecrans his pre-Civil War years had been punctuated by combat in

the Seminole and Mexican-American wars. In the latter struggle he had

attained momentary fame as an artillery battery commander in the Battle

of Buena Vista. Like Rosecrans he also tired of the army's peacetime routine and resigned

his commission in 1856. Marrying into wealth, Bragg was a gentleman

planter in Louisiana until the crisis of 1861 caused him to cast his lot

with the Confederacy. Again like Rosecrans, his rise in rank was speedy,

culminating in his promotion to full general in April 1862. Two months

later he took command of the troops he would rename the Army of

Tennessee. Following the abortive invasion of Kentucky, Bragg brought

his army back to Murfreesboro. When Rosecrans advanced upon him in late

December, Bragg responded with a vigorous attack; when Rosecrans held

firm, Bragg retreated.

Although no commander of the Army of Tennessee concerned himself

more with his soldiers' welfare, Bragg's men were generally unaware of

his feelings and most hated him.

|

While Rosecrans was a hero in the North, Bragg had few admirers in

the Confederacy. Like his opponent, Bragg was energetic, intellectually

able, and a man of unflinching integrity. While Rosecrans's headquarters

was noted for whiskey-fueled conviviality, Bragg's headquarters adopted

a spartan tone. Bragg led a disciplined life in both public and private

affairs, and his subordinates were expected to conform to his strict

code of conduct. This emphasis upon discipline made Bragg appear rigid,

brusque, and unsociable to all but a few close acquaintances. Trusting

no one, Bragg relied little on his staff and immersed himself in

administrative trivia. This self-inflicted burden resulted in frequent

bouts of dyspepsia and migraine headaches. Although no commander of the

Army of Tennessee concerned himself more with his soldiers' welfare,

Bragg's men were generally unaware of his feelings and most hated him.

Bragg's inability to relate to others and to understand their

shortcomings caused him to have the worst command climate in either

army. Only President Jefferson Davis, a man much like Bragg, retained

confidence in him in the summer of 1863.

|

GENERAL BRAXTON BRAGG (USAMHI)

|

When Bragg's army retreated from the battlefield of Stones River, it

withdrew no further than the vicinity of Tullahoma, Tennessee,

thirty-five miles to the southeast. There it too prepared itself for

another round of fighting. With Federal operations against Vicksburg

approaching a climax, Bragg was ordered to send part of his army to

Mississippi. Forced to adopt a defensive posture with the remainder, he

positioned his two infantry corps forward of the Duck River to protect

his railhead at Tullahoma. On the left Lieutenant General Leonidas

Polk's corps occupied Shelbyville, while on the right Lieutenant General

William Hardee centered his corps around the small village of Wartrace

on the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad. Polk's left was screened by a

cavalry division commanded by Brigadier General Nathan Bedford Forrest.

Major General Joseph Wheeler's cavalry corps performed a similar

function on Hardee's right. On June 20 the Army of Tennessee contained

an aggregate present of approximately 55,000 officers and men.

In addition to Bragg's army, serious terrain obstacles stood between

Rosecrans and Chattanooga. The first hurdle was a range of hills fifteen

miles southeast of Murfreesboro, behind which lay the camps of the

Confederate army. Next came the Duck and Elk rivers. If these obstacles

could be surmounted, the Federals would face the Cumberland Plateau, a

mountain range rising to an altitude of 1,800 feet. Beyond the

Cumberland Plateau flowed the Tennessee River, a barrier more than 1,200

feet wide. Beyond the Tennessee was a series of ridges, most notably

Sand and Lookout mountains, the latter rising to 2,200 feet. In the

mountains the roads were few and rough, and the army would find little

to eat. Rosecrans therefore would have to rely upon the Nashville and

Chattanooga Railroad for sustenance. Even if the Confederates could be

expelled from the region, the logistical challenge of supporting the

Army of the Cumberland in such inhospitable terrain would tax the

abilities of Rosecrans and his staff.

|

COLONEL JOHN THOMAS WILDER (LC)

|

Without losing sight of Chattanooga, Rosecrans divided his campaign

plan into segments. First, he would force Bragg and his army out of

Middle Tennessee, into the mountains and possibly beyond the Tennessee

River. Second, he would consolidate the ground won and stockpile

supplies for the subsequent mountain operations. Third, he would force a

crossing of the Tennessee River, a task in which neither the river nor

Bragg could be expected to cooperate. Finally, he would advance through

the mountains beyond the river, in hopes of either flanking the Army of

Tennessee out of Chattanooga or precipitating a major battle. To

implement this ambitious plan, the Army of the Cumberland had an

aggregate strength of 97,000 officers and men, although garrison details

reduced the field force considerably. The army was divided into four

infantry corps: the Fourteenth, under Major General George Thomas; the

Twentieth, under Major General Alexander McCook; the Twenty-first,

under Major General Thomas Crittenden; and the Reserve Corps, under

Major General Gordon Granger. Assisting the infantry was a Cavalry

Corps, under Major General David Stanley.

Rosecrans's primary objective was to drive Bragg from Middle

Tennessee through maneuver instead of battle.

|

Several practical factors influenced the design of Rosecrans's

campaign plan. First, logistical considerations required him to operate

generally along the line of the railroad, which would have to be

repaired as he advanced. Second, even with the railroad, he would have

to wait for the corn to ripen, so as to reduce the amount of forage

carried for his thousands of animals. Further, Rosecrans wanted to move

in conjunction with General Ambrose Burnside's expedition toward

Knoxville, Tennessee. Finally, he believed that a premature advance

might cause Bragg to withdraw out of reach and detach even more troops

for the defense of Vicksburg. A survey of the Confederate dispositions

indicated that a frontal assault on Bragg's army would prove far too

costly, while an advance on Bragg's left in the open country around

Shelbyville would not trap the Army of Tennessee. The final plan therefore

called for feinting at Bragg's left while simultaneously turning

his right in the more difficult country to the east. Rosecrans's primary

objective was to drive Bragg from Middle Tennessee through maneuver

instead of battle.

On June 23, 1863, elements of the Reserve Corps and the Cavalry Corps

headed toward Shelbyville to attract Bragg's attention to his left. At

the same time, the Twenty-first Corps began its long march around

Bragg's right flank. The weather now turned sour. Torrential rains began

on June 24 and continued virtually without intermission for the next

seventeen days, ruining the roads. On that day the Twentieth Corps

pushed into Liberty Gap, while the Fourteenth Corps attempted to force

its way through Hoover's Gap. Although McCook's men gained most of their

objective after stiff skirmishing, the greatest success came at Hoover's

Gap. There Colonel John Wilder's mounted infantry brigade, armed with

the seven-shot Spencer rifle, brushed aside Confederate pickets and

seized the entire gap. When Confederate forces counterattacked,

Wilder's men easily maintained their position. East of Thomas,

Crittenden's corps slogged deeper into the hills over increasingly

difficult roads. Rosecrans had expected to take two days to breach the

gaps, giving Crittenden ample time to get around Bragg's flank, but

Wilder's audacious move and the rain threatened to upset the Federal

timetable.

|

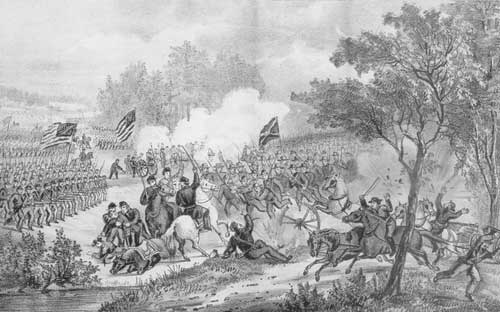

THIS CURRIER & IVES PRINT, THE BATTLE OF CHICKAMAUGA,

GEORGIA, IS AN EXAMPLE OF NINETEENTH-CENTURY ROMANTICISM OF THIS AND

MANY OTHER BATTLES. (LC)

|

On June 25 Thomas waited at Hoover's Gap while Crittenden continued

his march. The next day Thomas resumed his advance toward the town of

Manchester. Leaving one brigade at Liberty Gap, McCook started the

remainder of his corps westward after Thomas. Eventually learning that

his right had been turned, Bragg ordered a retreat. On June 27 Thomas

captured Manchester, but neither McCook nor Crittenden was able to join

him because of the poor condition of the roads. On Rosecrans's right

Stanley's cavalry drove Wheeler's Confederates from Shelbyville. By

that time both of Bragg's infantry corps were already moving southward

toward Tullahoma. In an effort to discover Bragg's intent, Rosecrans on

June 28 sent Thomas to threaten Tullahoma while McCook, Crittenden, and

Stanley concentrated at Manchester. At the same time Wilder's brigade

raided across the Elk River to strike the railroad in Bragg's rear at

Decherd, Tennessee. As Bragg's army entered the fortifications of

Tullahoma, Wilder's men reached the railroad and inflicted some damage

before being driven away.

As the Army of the Cumberland approached Tullahoma, Bragg ordered his

army to stand fast, but on June 30 he changed his mind. The incessant

rain had begun to swell the Elk River in Bragg's rear, threatening his

ability to retreat. That evening the Army of Tennessee quietly evacuated

its base. On July 1 Federal scouts probing Tullahoma's defenses found

them vacant. Learning that Bragg's army was in full retreat, Rosecrans

ordered Thomas and McCook to fix the Confederates in position, while

Crittenden and Stanley made another flank march to the east. Bragg's

lead was too great, however, and by noon the Army of Tennessee was

safely beyond the raging Elk River. Rosecrans now slowed the pursuit,

preferring to let Bragg go rather than corner him. Only too willing to

oblige, Bragg ordered his army to withdraw all the way to Chattanooga.

As Bragg's soldiers struggled over the mountains, Rosecrans's men

crossed the Elk River and occupied the towns of Decherd, Winchester, and

Cowan at the foot of the Cumberland Plateau. At a cost of only 560

Federal casualties, Rosecrans had successfully concluded the first

phase of his campaign for Chattanooga.

|

JOSEPH WHEELER, A MAJOR GENERAL AT CHICKAMAUGA, COMMANDED ONE OF BRAGG'S

TWO CAVALRY CORPS. (BL)

|

Amid a crescendo of criticism from soldiers and civilians alike,

Bragg's dispirited army established defensive positions around

Chattanooga in early July. The operations just ended had shown the Army

of Tennessee to be a balky machine. Polk and Hardee seemed united only

in their dislike for their chief. Wheeler's cavalry had furnished Bragg

bad intelligence of Federal movements, then had almost been destroyed at

Shelbyville. Quantities of supplies and some irreplaceable heavy

ordnance had been abandoned. Nevertheless, the army had retreated in good

order, if not in good spirits, and remained willing to contest the line

of the Tennessee River. Bragg deployed Polk's corps in the vicinity of

Chattanooga, with one brigade left on the Tennessee's north bank at

Bridgeport, Alabama, to provide early warning of Federal intentions.

Hardee's corps meanwhile was sent northwest of the city to guard

against a Federal thrust across the river between Chattanooga and

Knoxville. All told, Bragg's army contained approximately 52,000

officers and men by the end of July.

In a belated attempt to unify its efforts in East Tennessee, the

Confederate government on July 25 merged Major General Simon Buckner's

Department of East Tennessee into Bragg's Department of Tennessee.

Buckner's force added 17,800 troops to Bragg's command, but it also

expanded his area of concern northward to the Knoxville area. This

administrative action further degraded the command climate within

Bragg's department by bringing another enemy into the command

structure. Polk and Hardee already had little or no respect for Bragg

and were supported in their attitude by many of their principal

subordinates. Buckner's animosity toward Bragg stemmed from the unsuccessful

invasion of his native Kentucky in 1862, as well as the manner

in which his department had been abolished. The increased friction

represented by Buckner's arrival was momentarily mitigated by the

departure on July 14 of Hardee, who was transferred to Mississippi at

his own request. Hardee's replacement was Lieutenant General Daniel

Harvey Hill, a North Carolinian who had served with Bragg in Mexico.

In early August the War Department asked Bragg if he could take the

offensive given significant reinforcements from Mississippi. Bragg

responded that the geographical obstacles, his tenuous logistical

situation, and his weakness precluded an advance into or beyond the

mountains. If the Federals incautiously passed those barriers, however,

he believed that the time would be right for a counterstroke. Bragg

therefore contented himself with restoring discipline to his army,

apprehending deserters, and conserving his own increasingly shaky

health. Believing that the mountains and the Tennessee River were

sufficient to shield his front, he withdrew the brigade from Bridgeport,

leaving the territory beyond the river to Rosecrans. Keeping his two

infantry corps concentrated around Chattanooga, he relied upon his

cavalry to guard his flanks. Forrest's command covered the army's

right, extending northwest until it met Buckner's pickets near

Knoxville. Wheeler was responsible for the security of the army's left

as far as northern Alabama. While Forrest patrolled actively, Wheeler

permitted the bulk of his command to rest and refit far south of the

Tennessee.

|

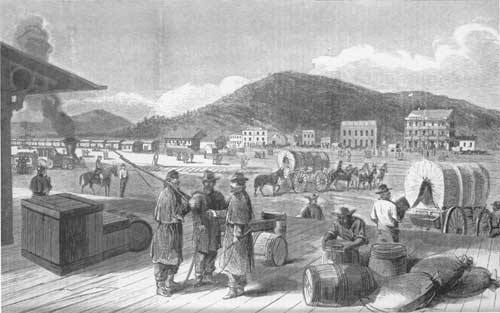

THE ARMY OF THE CUMBERLAND'S SUPPLIES ARRIVED BY RAIL TO STEVENSON,

ALABAMA, AND FROM HERE WERE TRANSPORTED BY WAGON. THE ARTIST WAS

LOOKING TO THE NORTHWEST IN THIS VIEW OF STEVENSON. (LC)

|

For six weeks after the Tullahoma operations ended, the Army of the

Cumberland remained in its camps at the foot of the Cumberland Plateau.

In order to establish a presence in the Tennessee River valley,

Rosecrans sent Major General Philip Sheridan's division of McCook's

corps to occupy Stevenson and Bridgeport, Alabama. Sheridan followed the

line of the railroad, which pierced the mountains in a 2,200-foot tunnel

near Cowan, Tennessee, then passed through Stevenson en route to its

crossing of the river on a 2,700-foot span at Bridgeport. The bridge had

been destroyed by the retreating Confederates, but the tunnel was

virtually undamaged. Of more immediate concern to Rosecrans was the

state of the railroad between Murfreesboro and Cowan. The large Elk

River bridge and several smaller spans had been destroyed, preventing

the rapid accumulation of supplies needed to sustain a further advance.

Rosecrans thus drove his engineers to rebuild the track as fast as

possible. Even with the railroad in full operation, the army could not

feed its thousands of animals without relying upon local forage.

Rosecrans therefore postponed further movement until the corn ripened

in the river bottoms.

|

MAJOR GENERAL GEORGE HENRY THOMAS (BL)

|

|

|