|

|

MCLEMORE'S COVE

Unable to defend the line of the Tennessee River

successfully, Braxton Bragg believed his best chance for victory lay

in using the mountains around Chattanooga to defeat William Rosecrans's

army in detail. Thus, when Federal units crossed Lookout Mountain and

threatened his railroad to Atlanta, Bragg evacuated Chattanooga on

September 8 and initiated his own campaign of maneuver. Moving southward

toward LaFayette, Georgia, Bragg learned that a Federal column was

entering McLemore's Cove, a V-shaped valley formed by Lookout Mountain

and a spur named Pigeon Mountain. The northern end of the valley was

open, and several gaps provided access to the valley from the east.

With his army screened by Pigeon Mountain, Bragg saw an opportunity to

destroy the Federals in the cove before they could receive assistance.

Accordingly, at 11:45 P.M. on September 9, he ordered Lieutenant General

Daniel Harvey Hill, whose corps guarded the gaps in Pigeon Mountain, to

send a division into the cove toward Davis Cross-Roads. At the same time

Major General Thomas Hindman was to enter the cove from the north and also drive toward

Davis Cross-Roads. The proposed victim of Bragg's plan was Major General

James Negley's division of George Thomas' XIV Corps. Convinced that

Bragg was in wild retreat, Rosecrans had pressured Thomas to accelerate

his pursuit. Although Negley was twelve hours ahead of Brigadier

General Absalom Baird's division, he entered the cove through Stevens

Gap on September 9. Negley's orders were to cross the cove, penetrate

Dug Gap in Pigeon Mountain, and drive on LaFayette. He began the

movement at 10 A.M. on September 10.

While Negley's 4,600 troops marched across the cove, Bragg's plan

began to unravel, Receiving his orders late, Harvey Hill uncharacteristically

claimed he was unable to participate. In contrast, Hindman moved

promptly and by 6 A.M. was only four miles north of Davis Cross-Roads

with 6,500 men. Without Hill, Hindman became overcautious and spent the

remainder of the day moving only one mile further. Bragg, meanwhile,

reinforced Hindman with Major

General Simon Buckner's corps. When Buckner arrived at 5 P.M., the

normally aggressive Hindman outnumbered Negley three to one, yet he did

not resume the advance. Told of the Confederate concentration by

friendly citizens, Negley that night withdrew his main body to a

defensive position just east of the crossroads. By the next morning,

when Hindman resumed his tentative advance, Baird's division had

arrived. As Hindman inched forward and some of Hill's men advanced from

Pigeon Mountain, Negley replaced his division with Baird's and began a

withdrawal to Stevens Gap. Apprised of the Federal retreat, Hindman

pushed forward but clashed only briefly with Baird's rear guard.

Incensed that his subordinates had bungled an opportunity to cripple

Rosecrans's largest corps, Bragg angrily ordered Confederate forces to

evacuate McLemore's Cove. Surrendering the initiative to Bragg,

Rosecrans now abandoned all thought of pursuit and attempted to

concentrate his scattered corps. Although Bragg would try again to

defeat the Federals before that concentration could be completed, his

best opportunity to do so was lost at McLemore's Cove.

|

Back at LaFayette Bragg saw another offensive opportunity when

Forrest reported that Federal units were moving across his front. This

time the mission went to Polk, whose corps was concentrated near Rock

Spring Church north of LaFayette. Polk's orders were simple: attack at

dawn on September 13. When morning came without any evidence of battle,

Bragg rode to the scene. He found no attack in progress and little

evidence of one in preparation. When Polk's skirmishers finally

advanced, they found no Federals in their front. Angry at another

apparent failure to destroy an exposed portion of the Army of the

Cumberland, Bragg returned to LaFayette. Although he believed Polk had

irresponsibly squandered an opportunity for victory, in fact none

existed on September 13. The Federals detected by Forrest had been the

remainder of Crittenden's corps moving from Ringgold to join Wood's

division at Lee and Gordon's Mill. By the morning of September 13

Crittenden's concentration at the mill was complete and the fleeting

chance for Confederate success was gone.

|

LEE AND GORDON'S MILL. AT THE CROSSING OF THE CHATTANOOGA-LAFAYETTE

ROAD OVER CHICKAMAUGA CREEK, BECAME ONE OF THE PRINCIPAL LANDMARKS

OF THE BATTLEFIELD. A POSTWAR MILL STRUCTURE OCCUPIES

THIS SITE TODAY. (LC)

|

At LaFayette Bragg learned of Federal units at Alpine, twenty miles

to the south west. Coupled with known Federal concentrations in

McLemore's Cove and at Lee and Gordon's Mill, these forces could be

interpreted as evidence of a massive double envelopment by the Federal

army. In reality McCook was scrambling to withdraw from Alpine, while

Thomas and Crittenden crouched defensively in their respective enclaves.

To Bragg, however, his position appeared precarious. Ever since the

evacuation of Chattanooga, Bragg's reserve stocks of food and

ammunition had been on railroad cars parked around Resaca, Georgia,

more than twenty difficult miles to the east. Those stores needed

protection, particularly if the army had to fight a large engagement

near LaFayette. With the enemy seemingly closing upon him, with his

subordinates unable or unwilling to do his bidding, and with his

logistical arrangements extremely tenuous, Bragg could hardly look with

equanimity upon the future. The only encouraging news was an unofficial

report that troops were arriving in Atlanta from Virginia with orders to

reinforce the Army of Tennessee.

For the next four days both armies labored to improve their

respective positions. Abandoning the offensive, Rosecrans attempted to consolidate

his scattered units, including elements of Granger's Reserve Corps,

before withdrawing to Chattanooga. If the Confederates left him alone,

he could soon muster a field force of slightly more than 62,000

effectives. At a council of war on September 15 Bragg's corps commanders

all agreed that a drive toward Chattanooga offered the best chance for

success. In preparation for an advance Bragg relocated his base from

Resaca to Catoosa Station near Ringgold. Around 3:00 A.M. on the morning

of September 17 he learned officially that Lieutenant General James

Longstreet was bringing a large contingent of troops to join him. Often

proposed, the transfer of the First Corps of the Army of Northern

Virginia to the western theater had finally been authorized by Jefferson

Davis on September 6, but Burnside's capture of Knoxville on September 2

had blocked the direct route from Virginia. Longstreet's 12,000 men had

been forced to detour over a succession of railroads in the lower South,

nearly doubling their transit time. In hopes that more of Longstreet's

men would become available for the offensive, Bragg postponed the

advance for one day.

|

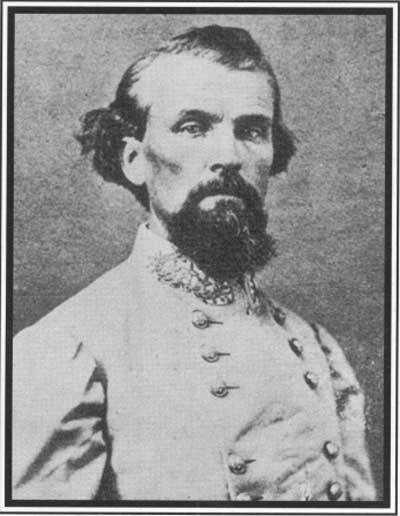

BRIGADIER GENERAL NATHAN BEDFORD FORREST (LC)

|

|

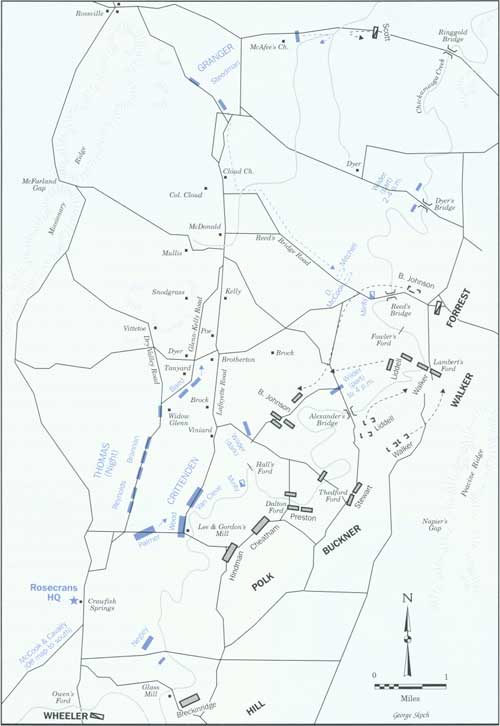

LIEUTENANT GENERAL JAMES LONGSTREET (LC)

|

On September 17 the last of McCook's corps reached the foot of

Stevens Gap, permitting Thomas to begin edging northward toward

Crittenden's position. That day Bragg rescheduled his offensive for the

morning of September 18. If Longstreet were there by that time, well and

good; if not, he could wait no longer. Bragg proposed to move most of

the Army of Tennessee northward beyond the Federal left flank at Lee and

Gordon's Mill, then cross Chickamauga Creek and drive southward, pushing

the Army of the Cumberland back into McLemore's Cove. The final

operations order specified four crossings over the Chickamauga from

north to south: Brigadier General Bushrod Johnson's division at Reed's

Bridge; Walker's Reserve Corps at Alexander's Bridge or Byram's Ford;

Buckner's corps at Thedford's Ford; and Polk's corps at Dalton's Ford,

Hill's corps would anchor the army's left, while Forrest and Wheeler

covered the army's northern and southern flanks respectively.

On September 17 the Army of Tennessee numbered just under 60,000

effectives, organized in four infantry and two cavalry corps. While the

troops were as good as the Confederacy had to offer, their leaders were

a mixed bag. Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk, 57, the senior corps

commander, was a West Point graduate but had spent virtually his entire

life in the Episcopal ministry. A friend

of Jefferson Davis but an inveterate opponent of Bragg, Polk tended

to obey orders in a maddeningly cavalier fashion. In contrast,

Lieutenant General Daniel Harvey Hill, 42, was a professional soldier

and a strong fighter. His querulous personality, however, made him a

difficult subordinate. Major General Simon Buckner, 40, was sulking over

the loss of his department and had retreated into passivity. Among the

infantry commanders, only Major General William Walker, 46, the

aggressive commander of the newly formed Reserve Corps, seemed to have

no animosity against his chief. Dashing Major General Joseph Wheeler,

27, had Bragg's confidence but had repeatedly failed to see beyond

romantic saber charges. Dour Brigadier General Nathan Bedford Forrest,

42, perhaps the most competent of all, held both Wheeler and Bragg in

contempt. Such men were now about to lead the Army of Tennessee into

battle.

Early on the morning of September 18 Brigadier General Bushrod

Johnson put his troops into motion, Initially taking the wrong road from

Ringgold he eventually got his command headed west on the Reed's Bridge

Road. As he neared an insignificant stream named Peavine Creek, his advance guard

encountered Federal cavalry pickets who fired and withdrew to their

supports. Johnson had found Colonel Robert Minty's brigade, whose

mission was to deny the Reed's Bridge crossing to the

Confederates. Outnumbered five to one Minty eventually retreated

across the bridge but was pursued too closely to destroy it. When

Johnson pushed quickly across the damaged span, Minty withdrew.

Resuming his advance, Johnson soon

reached William Jay's steam sawmill. There the Jay's Mill Road

continued south to Alexander's Bridge, while the Brotherton Road ran

southwest to join the main highway between LaFayette and Chattanooga.

Johnson had just started his troops on the Brotherton Road when Major

General John Hood joined the column from Catoosa Station. Taking

command, Hood ordered Johnson to use the Jay's Mill Road instead and the

column resumed its march in the gathering darkness.

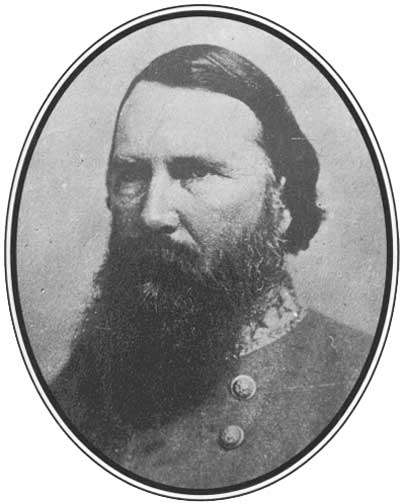

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 1863

Bragg failed to count on stiff Union resistance at the Chickamauga

crossings of Reed's and Alexander's bridges.

At 7:00 A.M., September 18, 1863, at Peavine Creek, Minty's brigade

met elements of Bushrod Johnson's division. Minty was slowly forced

back to Reed's Bridge by noon. Minty continued to delay until mid-afternoon

when elements of Forrest's cavalry corps caused him to

withdraw. The Confederates then crossed the bridge and turned south near

Jay's steam sawmill, en route toward Lee and Gordon's Mill.

At Alexander's Bridge. at noon, Walker's Reserve Corps met Wilder's

brigade, and Eli Lilly's battery. Walker was not able to cross and had

to reach the west side of the creek at another point, Lambert's Ford,

but not until 4:30.

Bushrod Johnson's approach from the north forced Wilder from

Alexander's Bridge. Wilder withdrew in front of Bushrod Johnson and

stopped the Confederates short of the Lafayette Road at dark, east of

the Viniard Farm. During the night Thomas's corps marched to the Kelly

Farm area.

|

Several miles south of Johnson, Walker's Reserve Corps attempted to

force its own crossing of the Chickamauga. Alexander's Bridge was

defended by elements of Wilder's mounted infantry brigade. Unlike

Minty, Wilder placed his primary line of defense west of the creek. The

firepower of his repeating rifles gave him confidence that he could hold

his position against great odds. Unaware of his technological

inferiority, Walker attacked Wilder with a brigade of Brigadier General

St. John Liddell's division. Although the unit suffered 105 casualties,

it could make no progress. Having learned a hard lesson, Walker left

Wilder's front and headed northward to Byram's Ford, an unguarded

crossing a mile downstream. There, far behind schedule, he finally got

his units across the creek and turned south in accordance with Bragg's plan.

Learning that Minty's loss of Reed's Bridge had compromised his left

flank, Wilder meanwhile withdrew to the southwest and established a new

blocking position east of the LaFayette Road.

|

REED'S BRIDGE WAS AN IMPORTANT CROSSING POINT OF CHICKAMAUGA

CREEK. A.R. WAUD'S ILLUSTRATION SHOWS FORREST"S CAVALRY

DRIVING MINTY'S UNION CAVALRY FROM THE SITE ON

SEPTEMBER 18, 1863. (LC)

|

|

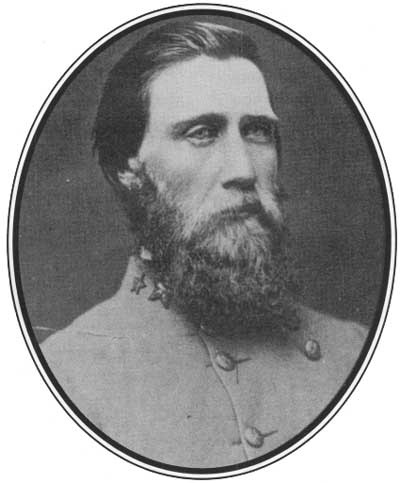

GENERAL JOHN BELL HOOD (LC)

|

As darkness fell on September 18, Bragg's offensive was seriously

behind its projected timetable. Johnson's division had marched southward

on the Viniard-Alexander Road until it halted in front of Wilder's

blockade. Walker had finally gotten his two small divisions west of the

creek, but his troops were scattered for a mile along the road behind

Johnson. Buckner had managed to push only one brigade across the creek

at Thedford's Ford, Polk was still facing Crittenden at Lee and Gordon's

Mill, while Hill's corps guarded crossing sites even further south.

Nevertheless, Bragg believed he had successfully turned the Federal

flank and next day would be able to descend upon Crittenden in a massive

coordinated attack. Unknown to Bragg, Rosecrans during the afternoon

unwittingly invalidated that assumption by ordering Thomas to pass

behind Crittenden and march northward throughout the night. Rosecrans's

decision placed the Federal army's left flank far north of where Bragg

expected to find it when the battle opened on the next day.

|

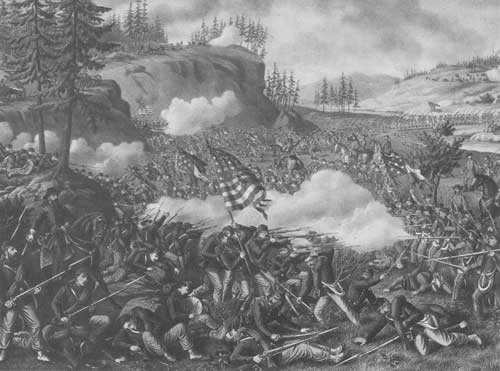

A COMMON MISCONCEPTION OF THE BATTLE OF CHICKAMAUGA WAS

THAT IT WAS FOUGHT ALONG THE BANKS OF CHICKAMAUGA CREEK.

THIS KURZ AND ALLISON LITHOGRAPH, CREATED BY ARTISTS

NOT PRESENT AT THE BATTLE, HELPED REINFORCE THIS

IMPRESSION. (LC)

|

|

ROSECRANS'S HEADQUARTERS ON SEPTEMBER 17 AND 18, 1863, WAS

THIS HOUSE AT CRAWFISH SPRINGS. IT ALSO SERVED AS A UNION HOSPITAL.

(BL)

|

Early on September 19, thirsty Federal soldiers from Colonel Daniel

McCook's brigade of Granger's Reserve Corps pushed beyond their picket

line in search of water near Jay's Mill. McCook's men had moved from

their camp near Rossville, Georgia, on the previous day in response to Minty's call

for assistance. Arriving near Jay's Mill long after Minty had departed,

McCook had captured several prisoners who indicated their unit had

recently crossed Reed's Bridge. Unwilling to approach the bridge at

night, McCook established a defensive position several hundred yards

northwest of Jay's Mill and waited for daylight. A similar distance

south of the mill, pickets from the First Georgia Cavalry also waited

for morning. Under orders to screen Hood's right and rear, Brigadier

General Henry Davidson of Forrest's Cavalry Corps had encountered

McCook's pickets and recoiled in the darkness. At dawn Davidson sent

the First Georgia forward again and they soon struck some of McCook's

men at a small spring near the mill. McCook meanwhile had sent a

regiment to destroy Reed's Bridge, but again it was only damaged.

Ordered back to Rossville by Granger, McCook withdrew with Davidson's

cavalrymen in pursuit. At the LaFayette Road he found Thomas, whose

leading elements had just arrived after an all-night march from Crawfish

Springs. McCook reported that a single Confederate infantry brigade had

crossed Chickamauga Creek and was trapped on the west side. In response,

Thomas ordered Brigadier General John Brannan's division to destroy the

Confederate unit. Brannan deployed Colonel Ferdinand Van Derveer's

brigade on the Reed's Bridge Road and Colonel John Croxton's brigade on

a woods path on Van Derveer's right. Colonel John Connell's brigade

followed the leading brigades as a reserve. Around 7:30 A.M. Davidson's

men encountered Croxton's skirmishers and sent them fleeing to their

main body. In turn, the horsemen recoiled from Croxton's advancing

regiments. Seeing the panic-stricken cavalrymen dashing from the woods,

Forrest formed Davidson's dismounted troopers in a defensive line just

west of Jay's Field. Croxton brought his five regiments up to face

Davidson and the battle was on.

|

|