|

|

THE HISTORIOGRAPHY OF CHICKAMAUGA

The first detailed accounts of the Battle of Chickamauga appeared in

newspapers published shortly after the conclusion of the action.

Inaccurate in many details, these hasty efforts nevertheless represented

the first attempt to analyze the battle. In 1883 the story of

Chickamauga assumed its modern form with the publication of The Army

of the Cumberland by Henry Cist. A partisan staff officer of

Rosecrans, Cist argued vigorously that the Federal defeat was primarily

due to the incompetence of staff Major Frank Bond and the malevolence of

Brigadier General Thomas Wood. Embellished over the years, Cist's

analysis remains today the prevailing account of Chickamauga's pivotal

events.

A decade later, Henry Boynton, another Rosecrans partisan and veteran

of the battle, became the dominant member of the Chickamauga Park

Commission. Like Rosecrans, Boynton maintained that Chickamauga had to

be fought to secure Chattanooga, and thus was a Federal victory. While

carefully locating many Federal markers, Boynton also skewed the

interpretation of the field in favor of certain units, especially his

own. The 1890 publication of Chickamauga battle reports in Volume XXX of

the War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and

Confederate Armies notwithstanding, Cist's and Boynton's highly

opinionated version of the battle was enshrined in the public mind by

1900.

|

HENRY VAN NESS BOYNTON

|

Cist and Boynton had their detractors, notably maligned participants

like Wood and veterans whose units had been slighted, but their

objections were ignored. In 1911, Archibald Gracie son of a Confederate

participant, published The Truth About Chickamauga. Initially

conceived as an effort to tell the Confederate side of the story,

Gracie's work ultimately became an attack upon Boynton's placement of

Federal units on Snodgrass Hill. Too narrow in scope and too technical

in nature to have much of an impact on Chickamauga historiography,

Gracie's book failed to produce a successful reinterpretation of the

battle.

Since Gracie's time, many biographers have addressed Chickamauga as

part of larger studies, often relying upon the Cist-Boynton versions in

the process. Especially notable in this regard was William Lamers's 1961

biography of Rosecrans, The Edge of Glory. In the same year

popular author Glenn Tucker published the first single-volume account of

the Chickamauga Campaign in modern times. Filled with personal

vignettes, Tucker's book relied heavily upon Cist's and Boynton's work

but tempered some of their more partisan judgments. For the next thirty

years, Tucker's Chickamauga: Bloody Battle in the West was the

standard account of the battle.

Although scholarship has greatly improved since Tucker's day, many

myths remain to be exorcised from the Chickamauga story. In 1971 Thomas

Connelly resurrected the reputation of the Army of Tennessee in

Autumn of Glory but continued the traditional bashing of Braxton

Bragg. Fortunately, recent work by Judith Hallock and Steven Woodworth

has finally begun to give Bragg his due. Some improvement has also been

made on the Federal side, with the publication in 1992 of Peter

Cozzens's This Terrible Sound, a full account of Chickamauga that

has superseded Tucker's work. Still, as Cozzens's massive study proves,

the Cist-Boynton version of events remains alive and well today.

|

THE GEORGIA MONUMENT UNDER CONSTRUCTION

IN EARLY 1899. THE FIGURE ON TOP POINTS THE WAY TO CHATTANOOGA. (NPS)

|

|

Unlike their commander, other soldiers of the Army of the Cumberland

remained on the battlefield. Around the Kelly Field Thomas's four

divisions still held their breastworks. On the ridge bending westward

from the Snodgrass House a less organized but equally determined stand

was made by men from many commands. First to reach the elevation later

known as Snodgrass Hill or Horseshoe Ridge was Negley with Colonel

William Sirwell's brigade. Negley had been on his way to join Thomas in

late morning when a staff officer had brought him a verbal order to

gather artillery on the ridge. Thomas wanted the artillery to cover his

left flank, but the message was garbled or Negley, ill with diarrhea,

misunderstood it. By the time Negley and Sirwell collected more than

forty guns, the Confederate breakthrough had occurred. Soon hundreds of

soldiers came pouring through the woods, many without organization or

commanders. Mostly from Brannan's and Van Cleve's divisions, many

demoralized men could not be rallied. Others decided to make a final

stand on the ridge.

Arriving with the mob was Brannan, who attempted to bring order from

the chaos. Asking Negley for assistance, Brannan received Sirwell's

largest regiment, the Twenty-first Ohio. Armed with the five-shot Colt

revolving rifle, the regiment anchored the right of the rallying

fragments. Doubting that Brannan's rabble could stand for long, Negley

decided to remove the artillery to McFarland's Gap. Not long after

Negley departed, Stanley's brigade arrived, having been forced westward

by Govan's attack. Although Stanley was soon wounded, his men occupied

the section of ridge immediately south of the Snodgrass House. They were

joined on their left by Harker's brigade, driven from the Dyer Field by

Kershaw. In such fashion a new Federal line formed, not by conscious

design but by the determination of hundreds of men to be driven no

further. First to test that line was Kershaw's brigade. Several times

Kershaw's regiments ascended the ridge, only to be beaten back by the

concentrated fire of the defiant Federals. On Kershaw's right,

Humphreys's brigade also approached the Federal line, but Humphreys

deemed the Federal position too strong and held his men back.

|

GORDON GRANGER'S TIMELY ARRIVAL WITH

PART OF THE UNION RESERVE CORPS, AS SHOWN IN THIS PAINTING RY HENRY A.

OGDEN, PROVED AN IMMENSE RELIEF TO GENERAL THOMAS. (COURTESY MICHAEL J.

MCAFEE COLLECTION)

|

While Kershaw and Humphreys battled Brannan's and Wood's men on the

eastern end of Horseshoe Ridge, Bushrod Johnson was ascending the

western end without opposition. After easily driving across the Dyer Field,

Johnson had gained a ridge overlooking the Federal trains fleeing

westward on the Dry Valley Road. For a time he contented himself with

using his artillery to stampede the teamsters while his infantry rested.

A little before 2:00 P.M.

he turned his division northward toward Horseshoe Ridge. Climbing a

spur on the western end of the wooded ridge, Johnson sensed that he was

positioned on the flank of Federal troops facing Kershaw and Humphreys.

Momentarily lacking McNair's (now Colonel David Coleman's) brigade,

which was still reorganizing east of the Dyer Field, Johnson deployed

Fulton's and Sugg's brigades before sending them toward the sounds of

firing. As they reached the top of the main ridge they were surprised to

meet a fresh Federal force climbing the opposite side.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

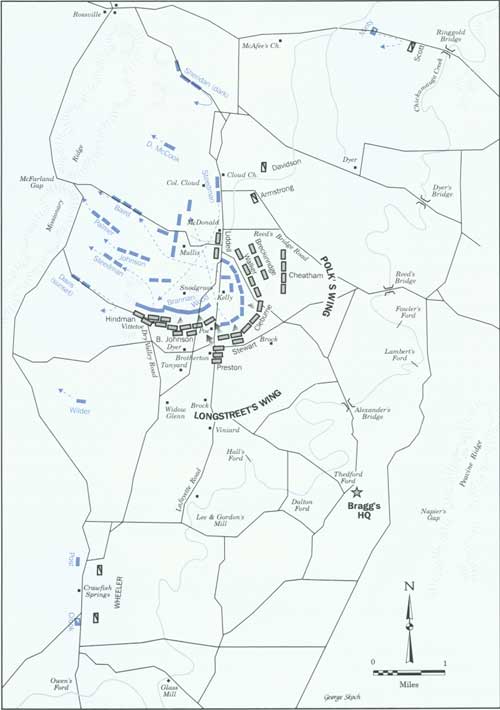

MID-AFTERNOON TO NIGHT, SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 20, 1863

Union elements that survived the breakthrough form a defensive

position on hills near the Snodgrass Farm and face mostly to the south.

Despite repeated assaults, Confederates are not able to take the ridge

until evening. Most of the Federal units have already withdrawn to

Rossville and established defensive positions along Missionary

Ridge.

At evening, Polk's wing renews its assault on the Kelly Farm

defenses. The Union line at this end of the field is also pulling back,

and the Confederates capture only a few hundred Federals.

The two Confederate wings will meet that night in what they would

later call a triumphal celebration, but most of the Federal army had

been able to withdraw in the direction of Chattanooga, contrary to

Bragg's plan of September 16.

|

The force that met Johnson consisted of two brigades of Brigadier

General James Steedman's division of Granger's Reserve Corps. Originally

posted at McAfee's Church east of Rossville, Granger and Steedman had

listened all morning to the sounds of battle three miles to the

south. At last, unable to restrain himself further, Granger ordered

Steedman's two brigades and Colonel Daniel McCook's brigade to march to

Thomas's aid. As they neared Thomas's flank they were harassed by some

of Forrest's dismounted troopers. Deflected westward from the LaFayette

Road by Forrest's artillery, Granger's men headed for the rear of the

Federal position on Horseshoe Ridge. Leaving McCook's brigade north of

the McDonald House to cover the rear, Granger and Steedman continued

southwestward until they reached

Thomas's beleaguered men. Ordered to prolong Brannan's line to the

west, Granger sent Steedman's division into action on the run. With

Brigadier General Walter Whitaker's brigade on the left and Colonel John

Mitchell's brigade on the right, Steedman stormed up the hill into the

teeth of Johnson's advance.

For the remainder of the afternoon the battle lines swayed back

and forth across the top of the ridge as repeated Confederate

assaults were repulsed, only to be renewed with greater effort.

|

The shock of Steedman's attack caused Johnson's men to recoil down

the hill. Following the retreating Confederates too closely, Steedman's

men found themselves exposed and withdrew to the crest of the ridge. For

the remainder of the afternoon the battle lines swayed back and forth

across the top of the ridge as repeated Confederate assaults were

repulsed, only to be renewed with greater effort. When Coleman's brigade

finally appeared, Johnson threw it into his subsequent attack. In

addition, his pleas for assistance resulted in Hindman's division being

sent to add weight to his efforts. Deas's and Manigault's brigades

formed on Fulton's left and participated in one charge but were so

exhausted from their earlier exertions that they were useless

thereafter. Similarly, Anderson's Brigade filled the gap between Johnson

and Kershaw and made its own unsuccessful assault against the hill.

Obviously, Johnson's and Hindman's men no longer had the offensive punch

needed to carry the commanding Federal position, especially after Van

Derveer's brigade arrived from Kelly Field to strengthen the defense.

As Bragg dolefully rode away,

Longstreet returned to the Dyer Field. There he finally began to impose

some central direction upon the disjointed Confederate assaults

fuvitilely smashing themselves against the ridge.

|

For some time the developing fight for Horseshoe Ridge did not gain

Longstreet's attention. After the initial breakthrough he visited his

right flank at the Poe Field, ordered Buckner to deploy more artillery,

then sat down to a convivial lunch with his staff. Summoned by Bragg, he

asked for reinforcements even though he had not yet committed his own

reserve, Preston's division. Depressed that another victory was slipping

from his grasp, Bragg claimed that Polk's right wing was too badly hurt

to provide assistance. As Bragg dolefully rode away, Longstreet returned

to the Dyer Field. There he finally began to impose some central

direction upon the disjointed Confederate assaults futilely smashing

themselves against the ridge. Missing since Hood had been carried

from the field, that central direction could possibly have swept the

haggard Federal defenders from their fiery

Gibraltar before nightfall. Now Longstreet would have to race the sun as

well as defeat the enemy. With only one last unit to deploy, he called

Preston's division forward.

|

THE DIORAMA AT THE CHICKAMAUGA AND CHATTANOOGA NMP

VISITOR CENTER DEPICTS THE NINTH OHIO INFANTRY CHARGING THE BRIGADE OF

JOSEPH KERSHAW'S SOUTH CAROLINIANS ON THE SLOPES OF

SNODGRASS HILL SEPTEMBER 20, 1863. (NPS)

|

|

SKETCH OF HORSES AND CAISSONS ON THE FIELD AFTER THE BATTLE.

(SOLDIER IN OUR CIVIL WAR)

|

Around 4:30 P.M. Brigadier General Archibald Gracie's brigade reached

the foot of Horseshoe Ridge. Taken under fire instantly, Gracie's troops

began the first of several attempts to seize the eastern end of the

ridge. On their left, Colonel John Kelly's brigade joined the assaults,

with similar lack of success. By the time Colonel Robert Trigg's brigade

arrived on Kelly's left, Gracie's and Kelly's men had lost their

momentum. Gracie had gained the edge of the first knoll southwest of the

Snodgrass House but could go no further, while Kelly was still at the

foot of the ridge. With Trigg's fresh regiments at hand, Preston decided

to make one last effort before darkness enveloped the field. Sensing a

slackening of Federal fire on his left, he sent Trigg up a ravine in

hopes of flanking the troops facing Kelly. Without opposition, the

brigade crossed the ridge, then

turned eastward. In the gloom Trigg's and Kelly's brigades encircled

remnants of three Federal regiments. Except for the wounded and the

dead, these regiments were the last Federals on Horseshoe Ridge. Where

had the remainder of the Army of the Cumberland gone?

Around 4:30 P.M., in response to an order from Rosecrans, Thomas

ordered a general retreat, beginning with the four divisions holding

Kelly Field. Reynolds's division began the delicate movement, with

Turchin's brigade in the lead. Finding skirmishers of Liddell's division

blocking the way, Turchin led a wild charge which brushed them aside and

cleared the McFarland's Gap Road. After Reynolds, it was Palmer's turn

to go. Having already sent Hazen's brigade to Horseshoe Ridge, Palmer

extracted his remaining two brigades with increasing difficulty. Seeing

the retreat, the Confederates redoubled their attacks against the

Federal position. As Johnson's and Baird's units struggled to disengage,

Stewart's, Cleburne's, and even some of Cheatham's men closed in around

them. Johnson's three brigades escaped relatively intact, but Baird lost

heavily, especially in prisoners. Leaping the works,

the Confederate infantrymen raised a victory shout that was heard far to the east,

where Bragg was sitting disconsolately on a log.

|

UNION WOUNDED FROM CHICKAMAUGA ARRIVING AT STEVENSON, ALABAMA, ON

SEPTEMBER 23, 1863. SKETCH BY J.F.C. HILLEN PROM FRANK

LESLIE'S ILLUSTRATED NEWSPAPER.

|

Before leaving Horseshoe Ridge, Thomas placed Granger in charge of

the defense, but Granger remained only a little longer than Thomas. When

he departed, no one coordinated the Federal withdrawal from the ridge.

As sunset approached, Steedman disengaged his division and quietly

withdrew to the north without being noticed by Bushrod Johnson or

Hindman. Similarly, Brannan and Wood managed the withdrawal of their

troops without reference to Steedman's departure. Left behind in the

center of the position were three regiments, all of which had been

temporarily attached to either Steedman or Brannan. The Twenty-second

Michigan and the Eighty-ninth Ohio regiments had entered the fight with

Whitaker's brigade and had been ordered to remain in place by one of

Steedman's staff officers. The Twenty-first Ohio regiment had been given

to Brannan by Negley early in the afternoon. It too was told by persons

seemingly in authority to hold its position with the bayonet.

Decimated by casualties and out of ammunition, the three regiments

heroically held their position until surrounded and captured by

Preston's Division.

...the Army of the Cumberland appeared to be evacuating

Chattanooga. Bragg therefore ordered a pause to reorganize

his shattered units and gather the spoils of war, which lay

everywhere on the field.

|

As darkness shrouded the battlefield of Chickamauga, few on either

side were aware that the struggle had ended. During the night Thomas

withdrew his intact units to positions around Rossville Gap and across

Chattanooga Valley. Behind this new line broken units reconstituted

themselves. Unaware that the Army of the Cumberland was gone, the Army of

Tennessee bivouacked where they lay, expecting to renew the contest on

the following day. Only gradually did the Confederate commanders realize

that they held the field alone. Immediate pursuit was tempting, but

practical considerations ruled it out. Bragg's army had lost more than

17,000 men killed, wounded, and missing. Many of the troops that had

arrived by rail had brought no transportation with them, and the battle

had seriously depleted the number of serviceable artillery horses. There

was no pontoon train available for crossing the Tennessee River.

Besides, the Army of the Cumberland appeared to be evacuating

Chattanooga. Bragg therefore ordered a pause to reorganize his shattered

units and gather the spoils of war, which lay everywhere on the

field.

Holding Missionary Ridge only long enough to regain its composure,

the Army of the Cumberland soon withdrew into Chattanooga. Rosecrans's

command was badly hurt, having lost more than 16,000 men killed,

wounded, and missing in the battle. Many of the wounded had been left to

the Confederates, either on the battlefield or at field hospitals that

could not be evacuated. Although the army had saved

most of its trains, large quantities of arms,

ammunition, and materiel had been left behind. Nevertheless, most of

the men were not demoralized and still retained confidence in Rosecrans.

Using old Confederate works as a foundation, engineers quickly designed

a strong defensive line. Digging with great energy, the Army of the

Cumberland soon felt secure from a frontal attack. Its supply situation

was much more tenuous because the Confederates controlled the easiest

routes to the Stevenson supply base. Still, as long as Chattanooga

remained in Federal hands, both Rosecrans and the Army of the Cumberland

could truthfully claim that the objective of the campaign had been

attained. Similarly, for Bragg and the Army of Tennessee, as long as

they were denied possession of Chattanooga the great victory of

Chickamauga would remain incomplete. Clearly, the iron hand of war had

not yet finished its work in the shadow of Lookout Mountain.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

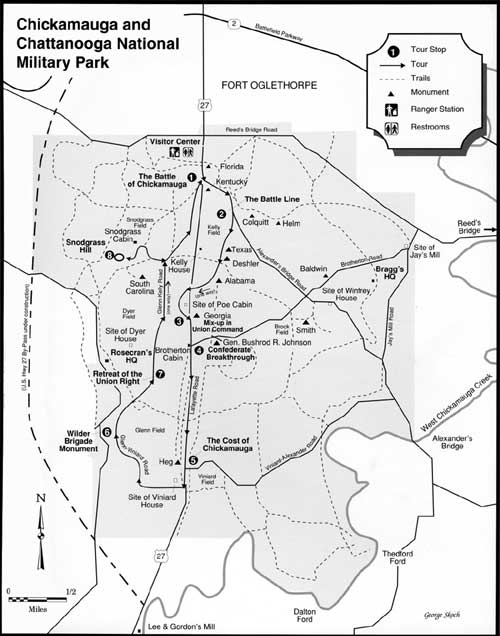

Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park

|

|

Back cover: Detail from The Battle of Chickamauga by

James Walker, courtesy of U.S. Army Historical Collection.

|

|

|