|

THE SECOND BATTLE OF MANASSAS

On September 8, 1862, Michigan general Alpheus S. Williams wrote home

about the recently concluded military events in northern Virginia.

Williams's descriptive language left no doubt that the results had been

unfavorable to the Union cause: "a splendid army almost demoralized,

millions of public property given up or destroyed, thousands of lives of

our best men sacrificed for no purpose." And with equal clarity,

Williams identified the source of the debacle: "I dare not trust myself

to speak of this commander as I feel and believe. Suffice it to say . .

. that more insolence, superciliousness, ignorance, and pretentiousness

were never combined in one man."

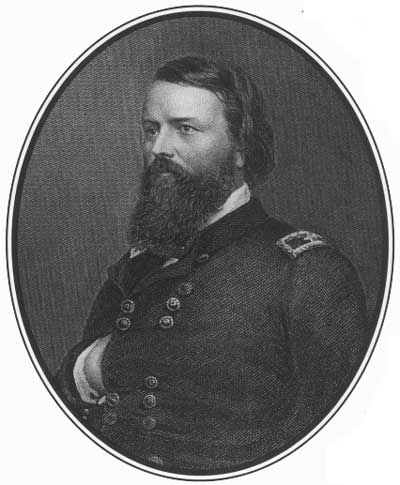

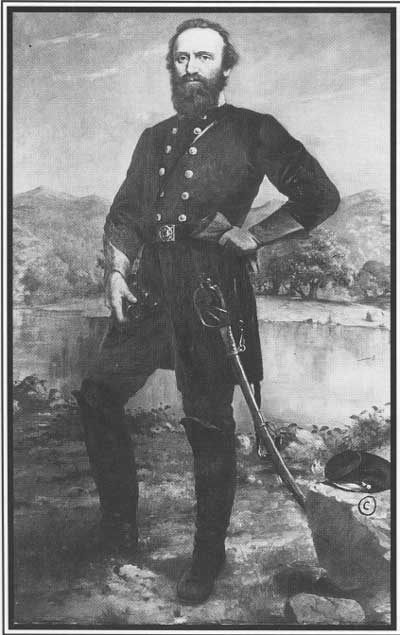

That man was John Pope, and the failed campaign over which he

presided has tarnished Pope's reputation for more than 130 years. Known

in the North as Second Bull Run and in the South as Second Manassas, the

actions between August 16 and September 2, 1862, marked the midpoint of

a momentous season that lifted the Confederacy's fortunes from the brink

of disaster to near independence. The gray-clad architects of this

achievement, Robert E. Lee and Thomas J. Stonewall" Jackson, would earn

widespread renown from their victory at Second Manassas while Pope

vanished into the backwater of history, confused about the cause of his

defeat until his dying day.

|

JOHN POPE (LC)

|

At the outset of the Civil War's second summer, the Union's prospects

appeared bright. Federal armies in the West had penetrated into northern

Mississippi and Alabama, New Orleans had fallen, and the navy threatened

to reduce Vicksburg and reopen the Mississippi River. Along the Atlantic

coast, Yankee forces had captured strong points in the Carolinas, and

the primary Northern weapon, the Army of the Potomac under its

charismatic but cautious leader George B. McClellan, bivouacked within

seven miles of the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia.

The principal disappointment amid this sea of encouragement occurred

in Virginia's Shenandoah Valley during May and June. An outnumbered

aggregration of Confederates under Stonewall Jackson had dispatched

portions of three Union commands and then slipped east to reinforce Lee

around Richmond. President Abraham Lincoln recognized that Jackson owed

much of his success to the fragmented nature of his Federal opponents.

On June 26 Lincoln rectified this problem by creating a unified command

out of the wreckage of Jackson's Valley victims, styling the new outfit

the Army of Virginia. To lead this force the president selected a

forty-year-old West Pointer born in Kentucky and raised in Illinois who

brought to the job an impressive portfolio.

John Pope combined family connections, military experience, and the

right politics to merit his appointment. He could trace his roots to

George Washington, but more important, the general's father had served

as an Illinois circuit judge and knew Lincoln well. Pope's father-in-law

represented an Ohio district in Congress and maintained a close

relationship with cabinet member Salmon P. Chase. Mrs. Lincoln's eldest

sister had married a Pope, so it was not surprising that in 1861 the

young officer accompanied the president-elect to Washington for the

inauguration.

|

WITH AN OUTNUMBERED CONFEDERATE ARMY, "STONEWALL" JACKSON EMBARRASSED

PORTONS OF THREE UNION ARMIES IN THE SHENANDOAH VALLEY. (LC)

|

Pope's prewar military career included competent service in Mexico

and on the frontier. He received a commission as brigadier general of

volunteers in 1861 and demonstrated his skill with a series of minor

victories in the West. Pope owed his promotion and transfer east,

however, more to his politics than to his military acumen. The Lincoln

administration had grown weary of McClellan's conservative approach to

the war, a philosophy embraced by the Democratic party and dedicated to

the restoration of the Union with minimal damage to the Southern fabric

of life. Pope had Republican leanings, radical ones at that, and he

offered the administration a counterpoint to the popular McClellan.

While there were those in the army who spoke highly of Pope, by and

large his fellow officers considered him vain, self-righteous, and

obnoxious. Various colleagues commented upon his quick temper and

rudeness in manner and characterized him as a braggart and liar. "We

looked forward with keen delight to see this inflated gas bag punctured

by the keen rapier of our great commander," chuckled one

Confederate.

|

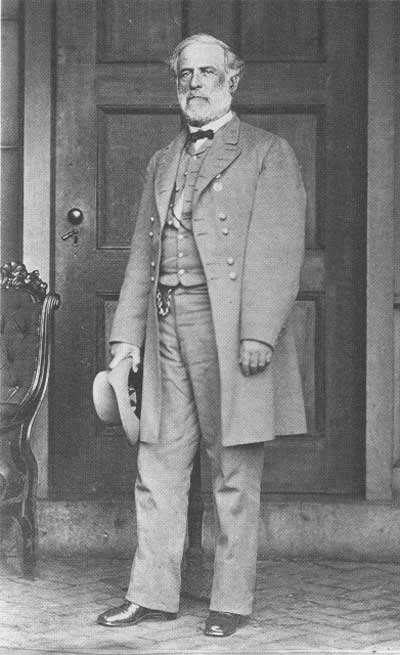

ROBERT E. LEE (LC)

|

Pope exacerbated his unenviable notoriety with a series of orders

issued shortly after his arrival in Virginia. Three of them reflected

the administration's desire to wage a harder war against the rebellious

population. They permitted appropriation of civilian property providing

reimbursement only to loyal citizens, authorized stiff penalities for

guerrilla activities, and required military-aged males within Union

lines to take a loyalty oath or be expelled beyond the limits of Federal

control. These measures, although only sporadically enforced and mild by

late-war standards, secured Pope the particular opprobrium of most

Confederates, including Robert E. Lee, who styled him a "miscreant."

Pope intended to inspire his troops with a formula for victory.

"Succes and glory are in the advance, disaster and shame lurk in the

rear," he exhorted his men.

|

Equally significant would be his proclamation of July 14 addressed to

the "Officers and Soldiers of the Army of Virginia" in which Pope

intended to inspire his troops with a formula for victory. "Success and

glory are in the advance, disaster and shame lurk in the rear," he

exhorted his men. Pope's rallying cry found favor with many of the rank

and file but rubbed the officer corps, who felt targeted by their new

commander's criticisms, the wrong way. It especially infuriated

McClellan and the Army of the Potomac, a result neither unintended nor

unanticipated by the administration. Pope's insistence that his new army

discard overconcern about lines of supply and possible retreat routes

(hallmarks of McClellan's timid generalship) would possess a humiliating

irony at the campaign's conclusion.

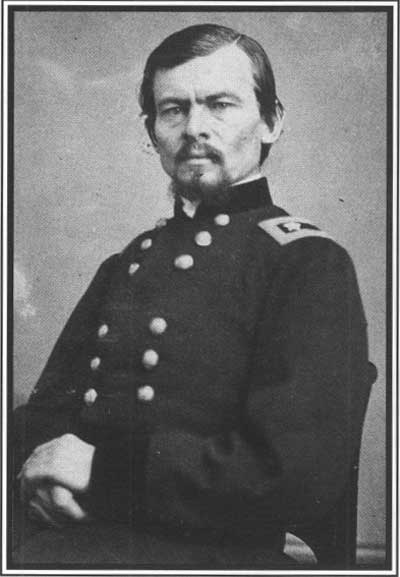

While Pope spent the first month of his tenure ruffling feathers from

Washington, his three leading subordinates assumed responsibility for

activities in the field. The German-American idol, Franz Sigel, led

Pope's First Corps. Sigel had replaced the dashing but modestly gifted

John C. Fremont, who refused to serve under Pope. Sigel's qualifications

for command rested with his ethnicity rather than his martial prowess.

One Federal officer aptly described him as "altogether excitable,

helter-skelter, and unreliable as a military leader."

|

FRANZ SIGEL (USAMHI)

|

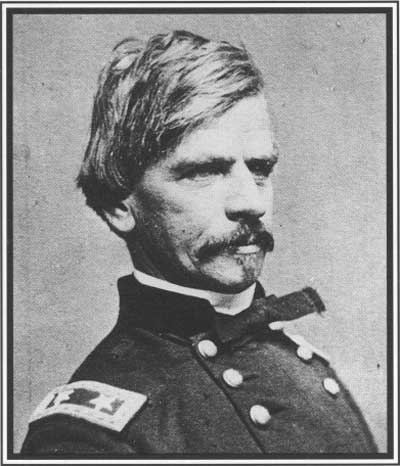

Nathaniel P. Banks commanded the Second Corps, previously known as

the Department of the Shenandoah. This prominent Massachusetts

politician had served as Speaker of the House of Representatives and

left the statehouse in Boston to accept an appointment as major general

of volunteers. Jackson had dominated the hapless Banks during the Valley

Campaign earning the New Englander ridicule beyond even what his

incompetency deserved. One observer noted that had Banks entered the

service as a line officer under a strict colonel, "he would, probably,

eventually, have become a good regimental commander."

|

NATHANIEL BANKS (USAMHI)

|

|

DURING THE SEVEN DAYS' BATTLES, LEE TURNED BACK MCCLELLAN FROM THE GATES

OF RICHMOND. (LC)

|

Pope's favorite underling led the Third

Corps, although Irvin McDowell enjoyed far less popularity among his men

than did Sigel or Banks. McDowell graduated from the United States

Military Academy and following a respectable prewar career presided over

the Union defeat at First Manassas in July 1861. This unfortunate legacy

translated into groundless rumors of McDowell's alleged duplicity,

symbolized by a ridiculous straw hat which some soldiers considered to

be a signal to protect him from Confederate fire. False reports about

McDowell's excessive drinking combined with factual depictions of the

general's gargantuan appetite to paint an unflattering and uninspiring

portrait.

Poor leadership compromised the army's enthusiasm that summer, but so

did the discouraging strategic circumstances confronting Pope. His

original mission included protecting Washington and the Shenandoah

Valley, operating against the Virginia Central Railroad, and, in concert

with McClellan's offensive, threatening Richmond from the west. By July

2, however, Lee had driven McClellan from the Confederate capital

during the Seven Days' Battles, and a month later the Army of the

Potomac received orders to board ships and return to northern Virginia

to unite with Pope. Thus Pope faced the challenge of opposing any

Confederate push to the north until McClellan's men could arrive,

preferably via Fredericksburg and up the line of the Rappahannock River.

Achieving all these goals with a dispirited army of barely 55,000 troops

presented Pope and his men with a daunting assignment.

Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia well understood the

strategic situation and its potential rewards. The fifty-five-year-old

Virginian had assembled a collection of disparate commands to defeat

McClellan during the Seven Days and in July detached three divisions

under Stonewall Jackson to keep an eye on Pope. As long as McClellan

remained within striking distance of Richmond, however, Lee could not

afford to deprive the capital of its mobile defenses.

|

AT THE BATTLE OF CEDAR MOUNTAIN ON AUGUST 9, JACKSON EARNED A HARD WON

VICTORY OVER NATHANIEL BANKS. (LC)

|

|

THOMAS J. "STONEWALL" JACKSON (LC)

|

Early in August, Lee had accumulated a variety of evidence that

foretold the departure of the Army of the Potomac from its position

below Richmond. Then on August 9 Jackson thrashed Banks in a convincing

if imperfectly fought engagement at Cedar Mountain north of the Rapidan

River, intimidating Pope and seizing the initiative from the Federals.

McClellan's imminent flight and Banks's defeat offered Lee the

opportunity he coveted. He ordered the right wing of his army under

James Longstreet (the Confederate government had not yet authorized the

formation of corps) to march northwest and join Jackson near

Gordonsville, a vital rail junction linking Richmond with the Shenandoah

Valley and northern Virginia. Lee's job would be to "suppress" Pope

before McClellan could reinforce him.

Jackson and Longstreet brought some 55,000 soldiers to the task, most

of them veterans of the victories around Richmond, and Lee's lieutenants

suffered from none of the shortcomings that handicapped Pope's corps

commanders. James Longstreet, a classmate of Pope's at West Point, was a

forty-two-year-old transplanted Georgian. He distinguished himself as

Lee's most effective subordinate during the Seven Days and would remain

a trusted, if occasionally controversial, member of Lee's inner circle

throughout the entire war. Jackson's fame exceeded Lee's at this stage

in history. The Virginian's reputation earned at First Manassas and in

the Valley made him the most admired (and feared) figure in Confederate

gray.

Indeed, it was Stonewall who urged Lee that the united Rebel army

should strike Pope immediately. Two small divisions under Jesse L. Reno,

a portion of Ambrose E. Burnside's North Carolina command, had already

arrived via Fredericksburg augmenting Pope's strength along the Rapidan.

If the Confederates moved quickly against the Federal left flank, they

could sever the reinforcement pipeline from Fredericksburg and catch

Pope's whole army with the Rappahannock River at its back, possibly

crushing it in the process.

|

J.E.B. STUART (LC)

|

Lee agreed but opted to delay the attack until Southern cavalry under

his nephew, Fitzhugh Lee, could execute a raid to destroy the Orange

& Alexandria Railroad bridge across the Rappahannock in Pope's rear.

By August 17 both Longstreet and Jackson poised in concealed positions

south of the Rapidan waiting for Fitz Lee and the signal to launch the

offensive scheduled for the next day.

Unfortunately for the Confederates, no one had told the young

cavalryman that Lee's plan depended upon his prompt appearance. Fitz Lee

tarried en route to collect supplies, forcing his uncle Robert to

postpone the advance. Even these revised plans came to grief when on the

night of the seventeenth a mounted Union patrol splashed across an

unguarded ford on the Rapidan and surprised Confederate cavalry

chieftain J.E.B. Stuart at his headquarters early the next morning.

Stuart barely made good an escape which cost him his cape, a new plumed

hat, and a great deal of pride. One of Stuart's aides did fall captive

to the Union intruders, surrendering two satchels of dispatches he

carried containing Lee's orders for Pope's undoing.

Thus warned of his impending demise, Pope began a hasty withdrawal to

the Rappahannock, crossing that watery barrier on the night of the

nineteenth to twentieth. "We little thought that the enemy would turn

his back upon us this early in the campaign," Lee told Longstreet in a

feeble attempt to joke about the disappointing turn of events. The

Confederates pursued, many of them fording the Rapidan "guiltless of any

clothing below the waist" but could not prevent Pope from placing the

Rappahannock between them and their quarry. The Federals thus scored the

first strategic point of the new campaign.

As the armies glared at one another from opposite banks of the

Rappahannock, each commander confronted a quandary. Pope had to provide

a secure corridor for reinforcements from the Army of the Potomac. Those

fresh troops might arrive from Fredericksburg, requiring Pope to protect

his left flank downstream on the Rappahannock. McClellan's units could

also disembark on the Potomac at Alexandria and employ Pope's direct

supply line, the Orange & Alexandria Railroad, to reach the front.

Pope knew that this avenue might be breached by skirting his right flank

and gaining his rear, necessitating Federal vigilance along the upper

Rappahannock. The man in charge of coordinating the rendezvous between

Pope and McClellan, General in Chief Henry W. Halleck, found his task

overwhelming and provided Pope little guidance. Halleck did encourage

McClellan to hasten the movement of his army to northern Virginia, but

"Little Mac" pursued his assignment with glacial speed, a function both

of his natural inclination and his loathing for the arrogant Pope.

|

RAILROAD BRIDGE ON THE ORANGE & ALEXANDRIA LINE. (USAMHI)

|

|

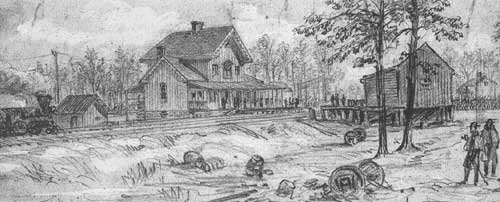

ON THE NIGHT OF AUGUST 22, STUART LED A DARING RAID ON POPE'S

HEADQUARTERS LOCATED AT CATLETT STATION. (LC)

|

Lee's dilemma centered on the realization that he must find a way to

engage the Federals. But forcing a downstream crossing of the

Rappahannock would expose his army to an attack from the direction of

Fredericksburg while shortening the distance that Union reinforcements

must cover to reach Pope. Thus the Confederate commander looked upstream

to the north and west to find the means of outwitting Pope's

defenders.

On August 21 a small body of Southerners slipped across the river at

Beverly Ford, but the Federals reacted quickly and Lee recalled his men.

The north side of the Rappahannock physically dominated the south bank,

and Pope skillfully exploited his geographic advantage. Consequently,

Lee shifted even farther upriver, authorizing Jackson to cross at

Sulphur Springs, nine miles above Beverly Ford, and approving "Jeb"

Stuart's suggestion to conduct a cavalry raid behind Pope's lines.

On August 22 Jackson managed to maneuver a reinforced brigade with a

battery of artillery across the river before dark. Heavy downpours that

night swelled the Rappahannock beyond fording stage, however, and

Jackson worked furiously the next day to reestablish contact with his

isolated and vulnerable units.

Meanwhile Stuart led some 1,500 troopers on a daring ride around

Pope's right, descending after dark on Catlett Station along the Orange

& Alexandria Railroad. Not only did Catlett provide a home for most

of Pope's headquarters impedimentia, but the railroad bridge over nearby

Cedar Run offered a tempting target for Stuart's raiders. If the

Confederates could destroy that span, Pope's supply line would he broken

and, perhaps, the Federals would be compelled to relinquish their

tenacious grip along the Rappahannock.

One of the marauders remembered that at 7:30 P.M., in the midst of a

torrential thunderstorm, "the bugles rang out . . . half a note of the

stirring call—the rest was drowned by a roar like Niagara. From two

thousand throats came the dreaded [Rebel] yell, and at full gallop two

thousand horsemen came thundering on." The attack caught the

rear-echelon headquarters staff and their small infantry guard by

complete surprise. "The cavalry rode among the tents and their shock

knocked some of the officers out of bed," said one Union observer.

"Every man, white and black, high and low, fled on his own hook." While

some of Stuart's despoilers pillaged the well-stocked encampment, others

attempted in vain to set fire to the saturated bridge over Cedar Run.

After midnight Stuart rounded up his high-spirited horsemen and headed

back for safe crossings on the upper Rappahannock.

|

ON AUGUST 24, LEE ISSUED ORDERS THAT WOULD SEND JACKSON AND HIS 24,000

MEN ON THE MARCH AROUND POPE'S ARMY. (I WILL BE MOVING WITHIN THE

HOUR BY MORT KÜNSTLER COPYRIGHT 1993.)

|

Stuart's failure to destroy the railroad bridge robbed the Catlett

raid of its primary strategic potential. The beau sabruer did, however,

assauge his bruised ego by avenging the loss of his plumed hat. Among

the prizes gathered at Pope's headquarters tent was the Union general's

full-dress uniform coat. Stuart wrote Pope suggesting "a cartel for the

fair exchange of the prisoners," to which he received no response. As a

result, Stuart had Pope's splendid garment displayed in the picture

window of a Richmond store and elsewhere in the Confederate capital,

where it attracted crowds of "amused spectators."

More meaningfully, Stuart showed Lee captured correspondence

verifying the rapid approach of McClellan's men from both Fredericksburg

and Alexandria. In fact, John F. Reynolds's division had already reached

Kelly's Ford on the Rappahannock while the rest of Fitz John Porter's

Fifth Corps marched a day behind. Samuel P. Heintzelman's Third Corps

had landed in Alexandria and awaited transportation to the front. Clearly

the window for Lee to strike at Pope under numerically favorable

circumstances was closing fast.

|

|