|

|

"I SHALL NOT SPARE MYSELF—"

Chinn Ridge, August 30, 1862, the Twelfth Massachusetts Infantry was

engaged in the heat of their first substantial battle. Their colonel,

brandishing his sword and riding along his line of men, shouted

encouragement in an effort to keep them in formation. Suddenly, a bullet

pierced his wrist and entered his right breast, causing the colonel to

fall from his horse. His adjutant was able to drag the colonel under

some bushes nearby. Remaining hidden, they were able to avoid detection

by lead elements of the Confederate army. Caught in the maelstrom of

battle, their pleas for help went unanswered by Union soldiers engrossed

in the fight.

Finally having been discovered by the Confederates, the adjutant

begged his captors to take the colonel with them. When they refused, he

pleaded to be allowed to remain with the colonel until medical help

could arrive. Being denied, the adjutant was forced by the Confederates

to leave at gun point but was promised that an ambulance would be sent

back for the colonel.

|

FLETCHER WEBSTER (LC)

|

Left on the field, the colonel received assistance from several

different Confederate soldiers. Knowing that he would soon die, the

colonel gave one of these soldiers, Ludwell Hutchison of the Eighth

Virginia Infantry, his wallet and asked that it be returned to his

family. Hutchison did so after the war had ended.

Two days after the battle, a party was sent out under a flag of truce

to retrieve the Union dead and wounded. Among them were two officers of

the Twelfth Massachusetts whose purpose it was to locate and retrieve

the colonel's body. With the guidance of a Confederate soldier, they

found and exhumed the body, discovering that it had been stripped and

robbed of a gold watch and over a hundred dollars. The body was sent to

Alexandria and embalmed. From there it was sent to the colonel's home

and on September 9, 1862, ten days after his death, the colonel was laid

to final rest in Marshfield, Massachusetts.

Thus was the fate of Colonel Fletcher Webster, the only surviving son

of the famous New England orator and statesman Daniel Webster. He

resigned his position as surveyor of the Port of Boston in 1861 to raise

and organize the Twelfth Massachusetts. The regiment titled itself the

"Webster Regiment" and elected Fletcher as colonel despite his limited

military experience.

During his preparation for the coming of his first real battle,

Fletcher, in a letter written to his wife on the morning of August 30

stated: "This may be my last letter, dear love; for I shall not spare

myself—God bless and protect you and the dear, darling children."

His zeal in battle that afternoon proved his letter to be correct.

In 1914 the survivors of the "Webster Regiment" wanted to mark the

spot where Colonel Fletcher Webster had died. However, after several

failed attempts to locate the site, they sought aid from other sources.

Finally, Ludwell Hutchison, upon being contacted, was able to pinpoint

the general site of the colonel's demise. Today, a boulder, taken from

the Webster family home in Marshfield occupies the solemn locale.

—Terri Bard

|

Lee realized that Longstreet would need help if he expected to wrest

Henry Hill from the stubborn Federals. He therefore dispatched Dick

Anderson's three brigades with a portion of Wilcox's division from the

Brawner farm about 5:00 P.M but Anderson would require time to reach the

rest of Longstreet's wing on Chinn Ridge. With Hood's and Kemper's

commands hors de combat, responsibility for maintaining the pressure

devolved upon Neighbor Jones. Jones shifted Benning's and G. T.

Anderson's Georgians toward Henry Hill and launched them on another

attack.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

THE CONFEDERATE TIDE CRESTS, 5:00 P.M. AUGUST 30, 1862

After sweeping the Federal troops off of Chinn Ridge, Longstreet's

men surged toward the Union line along the Manassas-Sudley Road. Saving

the Union army from complete disaster were several Federal brigades

stubbornly holding the slopes of Henry Hill. As dusk fell, the

Confederate attack was blunted, and Pope's army was able to reach safety

across Bull Run.

|

These 3,000 Confederates represented the largest single assault force

of Longstreet's whole offensive. Unfortunately, the Georgians' advance

lacked cohesion and discipline. The entire four-brigade Union line

punished Jones with a destructive fire that halted the Confederates in

their tracks. But just as the Southerners' propulsion seemed spent,

William Mahone's and Ambrose R. Wright's brigades of Anderson's division

materialized on the Confederate right. The portion of the Union defense

line opposite them enjoyed few natural advantages, and the outnumbered

Regulars posted there fought tenaciously to hold their ground. McDowell

committed his only reserves to the bitter battle on the Union left, but

Mahone and Wright outflanked these reinforcements and sent them reeling

toward the Henry house. As a result, a Rebel assault from the south

could now jeopardize the entire Federal position on Henry Hill and

potentially achieve Lee's ultimate goal.

|

UNION SOLDIERS SURVEYING THE RUINS OF THE HENRY HOUSE. (NA)

|

|

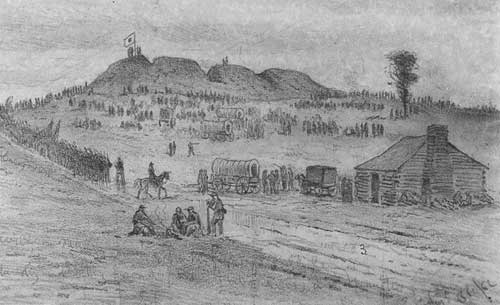

THE RETREATING ARMY OF VIRGINIA. (LC)

|

But Anderson declined to exploit the opening. For reasons that

remain unclear, the Confederates held fast on the southern end of Henry

Hill. Perhaps the growing darkness intimidated Anderson or the lack of

direct guidance from Longstreet and Lee left him hesitant to act.

Whatever the cause, Anderson's timidity squandered the opportunity

earned by three hours of the most intense fighting of the battle.

North of the turnpike, Stonewall Jackson also failed to apply timely

pressure against Pope's reeling legions, but his inactivity is easier to

explain. Greatly worn by their three days of incessant fighting and

facing, at least initially, the bulk of the Federal army, Jackson's

divisions did not begin their portion of the counterattack until 6:00

P.M. But when they did assault, "they came on like demons emerging from

the earth." Jackson overran a substantial number of Union artillery and

infantry units, but his advance coincided with Pope's orchestrated

withdrawal, contributing to the ease with which Jackson achieved his

captures. Despite mounting losses, by 7:00 P.M. Pope managed to

establish an unbroken line north of the turnpike aligning with the

Federal position on Henry Hill. Thus Jackson, like Longstreet, had no

choice but to remain content with a substantial tactical victory and

the attendant spoils of war while a defeated but intact Union army

prepared to leave the field.

Pope issued orders to retreat at 8:00 P.M. as the sounds of battle

ebbed away in the darkness. Thanks to its successful defense of Henry

Hill, most of the army could use the turnpike and its stone bridge

across Bull Run to effect its withdrawal. The gloom of the night and his

men's sheer exhaustion extinguished any notion Lee may have nurtured to

pursue or harass the Federal flight. By 11:00 P.M. Pope's troops had

left the field "with perfect coolness and in good order" and begun to

enter the relative safety of the Centreville defenses. Here Franklin's

pristine brigades cruelly taunted Pope's veterans as they trudged

toward waiting bivoaucs and a well-deserved night's rest.

Robert E. Lee spent the evening contemplating the outcome of the

battle. Although he informed President Jefferson Davis in Richmond that

"this army achieved today on the Plains of Manassas a signal victory

over the combined forces of Genls. McClellan and Pope," Lee knew that

his Federal opponents had escaped to fight another day. Should Lee's new

strategy succeed, that day would arrive soon.

|

THE STONE HOUSE NOW STANDS AS A SILENT REMINDER OF THE FIGHTING AT

MANASSAS. (PHOTO BY RAY HELLER)

|

The gray chieftain resurrected the morning's contingency plan to send

Jackson on another flank march around the Union right. Stonewall would

depart on August 31, gain the Little River Turnpike, and use that

highway to reach the Warrenton Turnpike at Germantown, seven miles east

of Centreville and between Pope and Washington. Longstreet would

skirmish with the Federals as he had done a week earlier along the

Rappahannock, pin them in place, then follow Jackson's route of march.

With luck Lee might achieve the knockout blow he failed to land at

Manassas. Should the stratagem founder, Lee could safely retreat in

several directions.

Pope and Halleck unwittingly played right into Lee's hands. Although

on the morning of August 31 Pope's officers voted to retire into the

Washington fortifications, a message from Halleck suggested that they

stay at Centreville. Pope concurred, thus setting the stage for another

one of Stonewall's immortal flanking maneuvers. But Jackson's troops

had reached their physical limits. They covered barely ten miles on

August 31, encamping at Pleasant Valley Church on the Little River

Turnpike.

On September 1 Stonewall resumed his march but quickly encountered

Union patrols, erasing the vital element of secrecy from his operation.

Jackson decided to halt at mid-morning near an old mansion known as

Chantilly and await Longstreet's arrival. Pope had indeed learned of

Jackson's approach and dispatched Reno's Corps under Isaac Stevens along

with Kearny's division to delay the Confederates while the rest of the

Federal army moved back from Centreville to protect the crossroads at

Germantown.

|

UNDER THE COVER OF DARKNESS, POPE'S DEFEATED ARMY WITHDREW ACROSS BULL

RUN TOWARD CENTREVILLE. (LC)

|

At noon Jackson resumed his cautious advance, halting two hours later

at Ox Hill, where the West Ox Road crossed the Little River Turnpike.

Here he deployed to wait for Longstreet and to learn from Lee about the

army's next move. But before the Confederates could be reunited,

Stevens and Kearny crashed into Jackson's lines about 5:00 P.M. amid a

violent thunderstorm. During the next two hours a battle ensued that one

Confederate characterized as "a beastly, comfortless conflict." Both

Stevens and Kearny were killed (no generals died at Second Manassas),

but the wild fighting ended indecisively about dark. That night as

Pope's army safely drew back toward the capital's elaborate earthworks,

Lee recognized that Pope had slipped his noose and that the Second

Manassas Campaign had finally concluded.

|

THE STONE BRIDGE, OVER WHICH POPE'S ARMY RETREATED ON THE NIGHT OF

AUGUST 30. (LC)

|

The Second Battle of Manassas had been one of the most costly

engagements of the Civil War. Lee lost 1,300 killed and more than 7,000

wounded during the three days of major fighting, while Pope suffered

nearly 10,000 casualties, not counting those captured or missing. In the

woods and fields from the Brawner farm to Henry Hill, along the

unfinished railroad and on Chinn Ridge, in unnamed hollows and behind

shattered trees, the bodies of the fallen littered the landscape.

Unburied corpses "who had been dashing and gallant soldiers only a short

week before . . . were swollen, blistered, discolored . . . and emitting

odors so thick and powerful that it seemed they might have been felt by

the naked hand."

Those who survived the battle faced an uncertain future, particularly

Union commander John Pope. On September 2 Halleck informed Pope that

Lincoln had named McClellan to assume control of the combined armies and

ordered Pope to conduct the troops to the Washington defenses. Little

Mac cantered out that afternoon and encountered Pope and his staff near

the head of the column. When word of McClellan's ascension filtered

through the army, cheers echoed up and down the ranks, One can only

imagine Pope's thoughts as he rode almost alone toward the Potomac and

the practical termination of his Civil War career.

|

ISAAC STEVENS (USAMHI)

|

|

ENCOUNTER AT LEWIS FORD

The evening of August 30, 1862, saw a struggling Union army preparing

to retreat over Bull Run. Reeling from Longstreet's crushing

counterattack, the Federals clung tenaciously to the slopes of Henry

Hill. Lee saw the chance to strike Pope's route of retreat and

administer the final blow to an already battered army. Lee called on the

masterful J.E.B. Stuart to administer this maneuver. Promptly, Brigadier

General Beverly H. Robertson with Colonel Thomas Rossers's regiment of

cavalry were ordered forward. In the hands of these Confederate

commanders lay the chance to envelop and destroy the entire Union

army.

Having received his orders, Robertson headed for Lewis Ford, south of

the Union army's line of retreat. Approaching the ford, Robertson

observed a "small squadron" of Union cavalry and ordered the Second

Virginia to charge them. Colonel Munford led his command in a race for

the enemy and scattered them. However, lurking behind the squadron was

General John Buford with his brigade of cavalry. Recognizing each other,

the forces charged one another. Numerically superior, the Union cavalry

soon had the advantage. Abruptly, the Confederates were reinforced and

the tide of battle changed. Federal forces fled toward the retreating

army. Having pursued, the Confederates soon found themselves behind the

Union army with darkness coming on and so withdrew to a safer position,

ending the skirmish.

Although lasting only a few moments, Lewis Ford was a vicious fight.

Confederates and Federals went toe-to-toe armed with only sabers and

pistols. Horses and riders were thrown together. One participant stated

that "the shooting and running, cursing and cutting that followed

cannot be understood except by an eyewitness." Caught in this melee,

Confederate Colonel Munford was dismounted and severely slashed across

his back. Union Colonel Brodhead was shot point-blank after refusing to

surrender. Even General Buford, who led the Union cavalry, was wounded

in the knee. In a violent, costly, and desperate battle, the Union

achieved much from the sacrifices made at Lewis Ford.

Lewis Ford, besides being one of the largest cavalry conflicts up to

that time, had two other important repercussions. First, General Buford

managed to withstand and delay the enemy long enough to save the Union

army. Had Buford not been there and stood up to the Rebels, Pope and his

entire army would have been lost. As Buford charged, a new and valuable

player entered the war. Union cavalry had never initiated a stand-up

fight until this time. From this point on, the cavalry of the Union was

going to make its presence on the battlefield known. The encounter at

Lewis Ford saved an army and demonstrated how Federal cavalry in the

Civil War was beginning to develop.

—Jason Litchblau

|

Two other Federal officers saw their reputations ruined at Second

Manassas. Although a court of inquiry cleared Irvin McDowell of any

wrongdoing, the perception of McDowell's incompetence, disloyalty, and

even treason resulted in his banishment to an inconsequential post in

California. Fitz John Porter fared even worse. Porter had been the most

outspoken of McClellan's officers in his denunciations of Pope, and he

cared little about who knew his feelings. Those sentiments added a

veneer of credibility to Pope's unfair accusation that Porter caused his

defeat at Second Manassas. A court-martial convicted Porter of willfully

disobeying Pope's attack orders on August 29, and Porter devoted the

next twenty years to restoring his good name.

The Northern populace cringed at the news from Manassas. Not only

did the casualty lists bring grief into thousands of homes, but the

likelihood of ultimate Union victory seemed dimmer than ever.

|

The Northern populace cringed at the news from Manassas. Not only did

the casualty lists bring grief into thousands of homes, but the

likelihood of ultimate Union victory seemed dimmer than ever. "To think

that we should be conquered by the bare feet and rags of the South,"

lamented a New York woman. Some Federal soldiers also lost faith in the

outlook for the war. "We had plenty of troops to whip them," protested

Robert Milroy, "but McDowell is a traitor and Pope is an incompetent

egotist. . . . Lincoln is blinded and under bad advisors and things will

go from bad to worse. I see no hope. Our govt. is lost and we must

bequeath war misery and anarchy to our children."

Events certainly appeared brighter for the Army of Northern Virginia

and the cause it championed. During a two-month period, Lee had moved

the war in the East from the doorstep of Richmond to the outskirts of

Washington. But he had paid a terrible human price for this

achievement. His weakened army lacked the firepower to fight on anything

like equal terms with his Union opponents. Moreover, northern Virginia

lay ravaged by military occupation and its prostrate farms could not

sustain even Lee's depleted numbers. The Confederate commander could

either withdraw south closer to reliable sources of supply or risk a

raid across the Potomac into Maryland and Pennsylvania, subsisting his

army off the bounty of Northern agriculture. The incomparable Virginian

chose the bolder of these two options and on September 4 began the march

that would result two weeks later in the Battle of Antietam.

|

A PERIOD LITHOGRAPH TITLED LEE AND HIS GENERALS. THE CONFEDERATE

VICTORY AT SECOND MANASSAS ENABLED LEE TO MOVE HIS ARMY NORTHWARD INTO

MARYLAND. (LC)

|

Understood in this context, the Second Manassas Campaign marked the

midpoint of Lee's grand summer offensive in 1862—a period that in

retrospect would mark the true high tide of Confederate fortunes.

Observers in foreign capitals took note of the apparent viability of

this new government whose armies could win victories within the shadow

of Washington. Voters in the North embraced Democratic candidates for

Congress who challenged the management and even advisability of the

conflict. And Abraham Lincoln deferred announcing the plan, his

preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, that would in the end add

transcendent meaning to the carnage of the Civil War.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

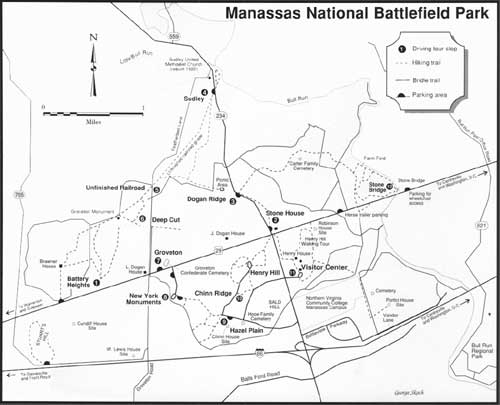

Manassas National Battlefield Park

|

|

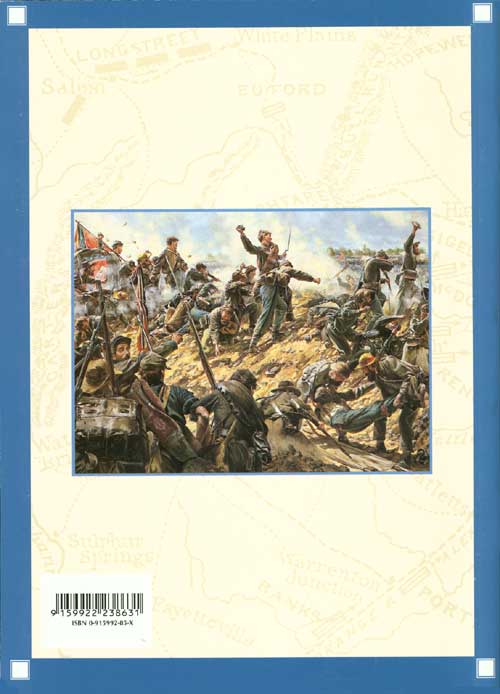

Back cover: The Diehards, by Don Troiani. Photograph courtesy

of Historical Art Prints, Ltd., Southbury, Connecticut.

|

|

|