|

RAIDING POPE'S PANTRY

On the evening of August 26, 1862, Jackson reached the Orange &

Alexandria Railroad at Bristoe Station, where he and his men derailed

two Federal supply trains and destroyed a quarter mile of track. Jackson

was soon unformed that Manassas Junction, located four miles north of

Bristoe, was lightly guarded. The junction was serving as the supply hub

for John Pope's army and was said to contain "stores of great

value."

Jackson quickly selected two regiments under the command of Issac

Trimble to capture the junction. After moving forward, the two regiments

quickly seized the depot and 300 prisoners.

Many of the soldiers reflected on the abundant supplies found at

Manassas.

"Jackson's first order was to knock out the heads of hundreds of

barrels of whiskey, wine, and brandy. I shall never forget the scene.

Streams of spirits ran like water through the sands of Manassas and the

soldiers on hands and knees drank it greedily from the ground."

Major W. Roy Mason

The Federal depot was "vast storehouses filled with . . . all the

delicacies, potted ham, lobster, tongue, candy, cakes, nuts, oranges,

lemons, pickles, catsup, mustard, etc. It makes an old soldier's mouth

water now just to think of the good things captured there. . . . Some

filled their haversacks with cakes, some with candy, others with

oranges, lemons, canned goods etc. I know one that took nothing but

French mustard . . . it turned out to be the best thing taken because he

traded it for meat and bread. It lasted until we reached Frederick."

Private John H. Worsham

21st Virginia Infantry

"I will not attempt to describe the scene I here witnessed for I am

sure it beggars description. Just imagine about 6000 men hungry and

almost naked, let loose on some million dollars worth of biscuit,

cheese, ham, bacon, messpork, coffee, sugar, tea, fruit, brandy, wine,

whiskey, oysters, coats, pants, shirts, caps, boots, shoes, socks,

blankets, tents, etc.. Here you would see a crowd enter a car with

their old confederate grays and in a few moments come out dressed in

Yankee uniforms; some as cavalry; some as artillerists; others dressed

in the splendid uniform of Federal officers . . . I have often read of

the sacking of cities by a victorious army but never did I hear of a

railroad train being sacked. I viewed this scene for almost two hours

with the most intense anxiety. I saw the whole army become what appeared

to me an ungovernable mob."

Chaplain James B. Sheeran

14th Louisiana

Infantry

That night, with Pope's army closing in on Manassas Junction,

Jackson's men set fire to the remaining supplies. He then moved his men

toward the old battlefield of Manassas to await the arrival of Lee and

Longstreet.

—Chris Bryce

|

John Pope indulged in another kind of feast on the night of August

27—an intellectual Bacchanalia featuring the stimulating brew of

glorious prospective victory. Learning of Jackson's strength and

whereabouts from Hooker's prisoners at Bristoe, Pope made plans "to bag the

whole crowd" of brazen Confederates the next day. He eagerly directed

his entire army to converge on Manassas Junction from the southwest,

west, and north.

|

GEORGE MCCLELLAN (USAMHI)

|

Although Pope's conception possessed admirable initiative and

aggressiveness, it ignored two fundamental factors. First, Pope's

success depended upon the unlikely eventuality that Jackson would

quietly remain at Manassas Junction until Pope's scattered divisions

could descend upon him from three directions of the compass. Second, he

ignored the existence of half of Lee's army, Longstreet's wing, which

Pope now knew to be on the march and in the vicinity of Salem. As one of

the campaign's early historians wrote a century ago, "the concentration

of the entire army on Manassas, ordered as it was on the evening of the

27th . . . . was the parent of much disaster."

Jackson had no intention of remaining stationary at the plundered

Union supply base. His strategic imperative depended upon bringing Pope

to battle, but only under circumstances favorable to the Confederates.

This meant that Lee's army must be reunited, but Jackson's couriers

informed him that Longstreet was at least a day's march away. Stonewall

would have to purchase that time by adopting a strong position from

which he could connect with Longstreet via Thoroughfare Gap. And if they

then hoped to attack Pope with advantage, Jackson had to discourage the

Union commander from retreating across Bull Run to assume a defensive

posture until McClellan joined him with the rest of the Army of the

Potomac.

|

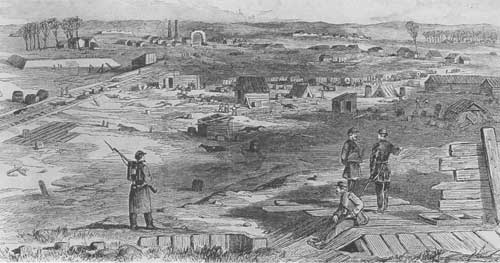

WHEN POPE'S ARMY ARRIVED AT MANASSAS JUNCTION, JACKSON WAS NOWHERE TO BE

FOUND. (LC)

|

|

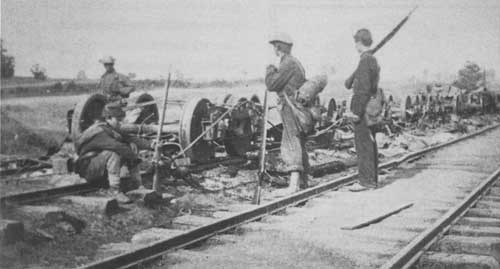

UNION SOLDIERS SURVEY THE DEVASTATED SUPPLY DEPOT AT MANASSAS JUNCTION

(USAMHI)

|

Jackson studied the map and discovered a location that satisfied his

criteria perfectly. Stony Ridge, a low rise 1,000 yards north of the

Warrenton Turnpike near the old Manassas battlefield, possessed all of

Jackson's required virtues. Its heavy woods would conceal the

Confederates but allow them a clear view of the highway that might take

Pope across Bull Run. Longstreet could link with Jackson there either

via the turnpike or a secondary road leading directly from Thoroughfare

Gap. Another byway connected Stony Ridge with Aldie Gap in the Bull Run

Mountains, offering an escape route for Jackson if Longstreet somehow

failed to arrive. Finally, the cuts and fills of an unfinished railroad

running along the base of Stony Ridge formed a ready-made entrenchment

for Jackson's outnumbered divisions. One thoughtful Confederate

considered Jackson's move to Stony Ridge "a masterpiece of strategy,

unexcelled during the war."

Taliaferro's division began the march at 9:00 P. M. August 27 along

the Manassas-Sudley Road reaching the turnpike near the famous Stone

House by midnight. Stonewall intended for Hill and Ewell to follow

Taliaferro's lead, but bewildered guides misdirected these troops across

Bull Run and in Hill's case all the way to Centreville. It would not be

until the next morning that Jackson's entire wing reunited on Stony

Ridge. Behind them Manassas Junction lay in charred ruins, a hollow

prize for the first Federal troops who appeared there late on the

morning of August 28.

In fact, nothing had gone just right for Pope this day. McDowell and

Sigel had become ensnarled on the roadways around Gainesville and

suffered a five-hour delay in their march toward Manassas. Struggling

through tangled terrain, Sigel stumbled cross-country toward Bristoe,

each step rendering his corps more irrelevant to the strategic

situation. McDowell finally pushed eastward on the turnpike about 10:00

A.M. Reynolds's division of Pennsylvania Reserves led the corps followed

by the four brigades of Rufus King. McDowell placed James B. Ricketts's

division in the rear with orders to peek over their shoulders toward

Thoroughfare Gap, alert to the appearance of Confederates at that

critical point. McDowell's precaution proved wise, as events would soon

demonstrate.

|

IRVIN MCDOWELL (NA)

|

|

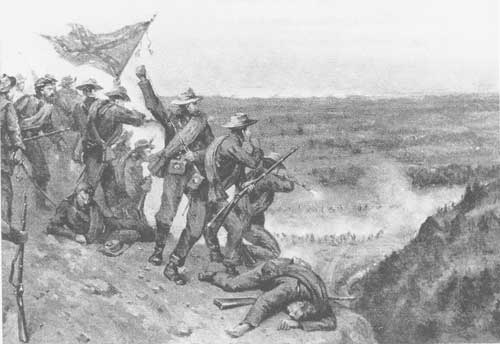

BATTLING THE FEDERAL SOLDIERS OF JAMES PICKETTS'S DIVISION, LONGSTREET'S

MEN FORCED THEIR WAY THROUGH THOROUGHFARE GAP. (LC)

|

The four divisions of Longstreet's wing who began their march in

Jackson's footsteps on the afternoon of August 26 covered a commendable

fourteen miles before sunset, but tramped only six miles on the

twenty-seventh. Lee, who traveled with Longstreet, allowed the pace to

be equally languid on August 28, a surprising concession considering

Jackson's perilous situation on the plains of Manassas. By late morning

Longstreet's leading brigades approached the potential chokepoint at

Thoroughfare Gap.

McDowell first learned of Longstreet's proximity from one of his

overworked cavalry regiments which had been attempting to block the

constricted mountain pass with a jumble of felled trees. On his own

initiative, McDowell turned Ricketts around and ordered him to use his

5,000 men to plug the bottleneck at Thoroughfare Gap. Ricketts arrived

in mid-afternoon and engaged two brigades of Georgians for several

bloody hours. Longstreet finally settled the affair by wisely

orchestrating a flanking movement on both sides of the gap, offering

Ricketts no choice but to retire his outgunned brigades to the east.

Longstreet then moved up and secured Thoroughfare Gap, leaving no

natural impediment to his unification with Jackson the next day.

Meanwhile, John Pope continued to indulge his fixation with Jackson. The

Union commander had snatched a handful of Confederate stragglers at

Manassas Junction, who misinformed him that Stonewall had marched just a

few hours earlier toward Centreville. Hill and Ewell had, in fact,

mistakenly crossed Bull Run the previous night, but by midday August 28

they had rejoined Taliaferro along Stony Ridge. Pope accepted the

prisoners' inaccurate intelligence and redirected his army toward

Centreville, determined to annihilate Jackson no matter where the wily

Confederate might go.

|

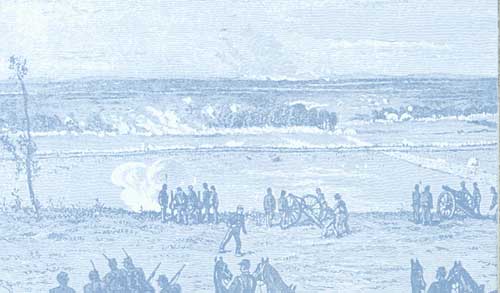

CONFEDERATE ARTILLERY POSTED NEAR THE BRAWNER FARM PINNED DOWN THE

FEDERAL SOLDIERS OF RUFUS KING'S DIVISION ALONG THE WARRENTON TURNPIKE.

(BL)

|

Jackson shared Pope's enthusiasm for a fight. His tired but contented

men, "packed like herring in a barrel in the woods behind the old

railroad," lounged in the August heat awaiting the word to spring on

their unwary prey. That word arrived shortly before noon when Reynolds

appeared on the turnpike at the head of McDowell's corps just west of

Jackson's concealed right flank. Jackson arose "like an electric shock"

and ordered Ewell and Taliaferro to move to the attack. But before they

could deploy, their quarry had vanished, disappearing down Pageland

Lane, a country road that would take the Federals toward Manassas as

their current orders demanded. A frustrated Jackson prowled along his

lines hoping for another opportunity to strike the Yankees, anxious also

to learn about Longstreet's progress.

Toward evening Stonewall received good news on both fronts. A courier

reported Longstreet's success at Thoroughfare Gap, suggesting that Old

Pete would connect with Jackson's right early the next day. Much

relieved, Jackson sought a few moments of rest, indulging in one of his

celebrated impromptu naps in the comfort of a fence corner. He had not

slumbered long when breathless messengers pounded up and announced the

presence of a large column of bluecoats marching eastward on the

turnpike across the Confederate front. Jackson mounted in an instant and

rode off to see for himself. On the open slope of a pasture belonging to

John Brawner's rented farm, northwest of the hamlet of Groveton, Jackson

paraded in full view of the passing Federals. The Northerners took

little notice of the lone rider whom they assumed to be a mere cavalry

scout. Jackson absorbed the scene for a few moments and then returned to

his fence-corner headquarters. "Bring out your men, gentlemen," he told

his subordinates. The Second Battle of Manassas was about to begin.

Stonewall's Federal targets belonged to Rufus King's division. King,

the forty-eight-year-old scion of a distinguished New York family, was

McDowell's favorite division commander. Perhaps their warm relationship

induced McDowell to overlook his subordinate's failing health. King had

suffered an epileptic seizure on August 23 and would experience a

recurrence of his malady on the afternoon of the twenty-eighth, leaving

him incapable of taking the field during the most critical time in his

division's history. Of course, as his four brigades swung east on the

turnpike in the waning sunlight, no one could know that the next few

hours would prove so consequential.

King's men were responding to orders from Pope received at 5:00 P.M.

directing the reconcentration against Centreville. The other divisions

of McDowell's corps, Reynolds's and Ricketts's, had proceeded toward

Manassas and engaged Longstreet at Thoroughfare Gap respectively, so

only King was in position to move immediately toward the new goal. A

unique brigade of Westerners led by John Gibbon marched with King's

6,000 men. Gibbon issued his Wisconsin and Indiana soldiers

broad-brimmed black hats, lending them a distinctive appearance. Only

one of Gibbon's regiments, the Second Wisconsin, had any combat

experience under its belt, but the events of August 28 would change all

that.

|

COMPANY I OF THE SEVENTH WISCONSIN VOLUNTEERS. (COURTESY STATE

HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN)

|

The "black hats" followed John P. Hatch's lead regiments and preceded

Abner Doubleday's and Marsena R. Patrick's brigades in King's line of

march. "Drowsily we swung along the grassy roadside, taking in the soft

beauty of the scene," rhapsodized one of King's soldiers. The terrain

around them was mostly open. North of the turnpike, the ground rose

gently for 500 yards toward the Brawner house and its adjacent orchard.

The unfinished railroad lay 1,000 feet beyond, about one-quarter mile

south of the wooded slopes of Stony Ridge. A thirty-acre stand of

hickory and oak, Brawner's Woods, straddled the turnpike southeast of

the dwelling.

"Our brigade moved along the turnpike on that quiet summer evening

as unsuspectingly as if changing camp," remembered an officer in the

Sixth Wisconsin. "Suddenly the stillness was broken by six cannon shots

fired in rapid succession by a rebel battery, point blank at our

regiment." General Gibbon reacted quickly to this unexpected fire by

unlimbering his own guns, Battery B, Fourth United States Artillery,

which responded to the Confederate shelling coming from the Brawner

farm. Additional Southern ordnance entered the fray, the "exchange of

metallic compliments [becoming] very profuse indeed."

Jackson's salvos succeeded in halting King's entire division. Hatch

had proceeded beyond the focus of the Confederate fire, but Patrick's

regiments fled for cover south of the highway while Gibbon's and

Doubleday's troops sought shelter in Brawner's woodlot along the road.

Those two brigadiers, assuming Jackson to be at Centreville, concluded

that this annoyance must be courtesy of Jeb Stuart's horse artillery.

Like most infantry commanders, Gibbon had little regard for cavalry in

an open fight, so he volunteered to send his veteran Second Wisconsin up

the hill to disperse the bothersome cannoneers and their mounted

supports.

The Second Wisconsin, known as "the Ragged Ass Second" because of the

condition of their trousers, numbered 430 officers and men. Their

colonel, Edgar O'Connor, had lost his voice that day and had to whisper

to his adjutant to convey the orders to advance. Shortly after 6:30 P.M.

O'Connor directed his troops through Brawner's Woods, emerging in the

fields southeast of the farmhouse. The Confederate batteries had already

limbered up and pulled away, but on the horizon appeared a long and

menacing line of butternut infantry.

These men belonged to the most renowned brigade in Lee's army, the

Stonewall Brigade from Virginia's Shenandoah Valley. Earning their

blood-stained fame at First Manassas and during the Valley Campaign,

Jackson's former command had been reduced to barely 800 bayonets in five

regiments. Despite their depleted ranks, a Confederate officer testified

that "it made one's blood tingle with pride to see these troops going

into action."

O'Connor deployed in line of battle, "the men grasping their pieces

with a tighter grip and expressing their impatience in low mutterings in

such honest, if not classic phrases, as, 'come on God damn you.'" When

the Virginians closed to within 150 yards, the Second Wisconsin let fly

a devastating volley. The Confederates shuddered, absorbed the blast,

and advanced to an old rail fence 80 yards from their blue-clad

opponents, where they at last returned fire. "Everything around us was

lighted up by the blaze of the musketry and explosion of balls like a

continuous flash of lightning," recalled a Confederate.

Gibbon began to realize that he faced more than a few troublesome

troopers. He ordered the "Swamp Hogs" of the Nineteenth Indiana under

their six foot-seven inch commander Solomon Meredith to support

O'Connor's left. The Hoosiers took position almost in the Brawner front

yard, where the Stonewall Brigade greeted them with a punishing sheet

of lead.

|

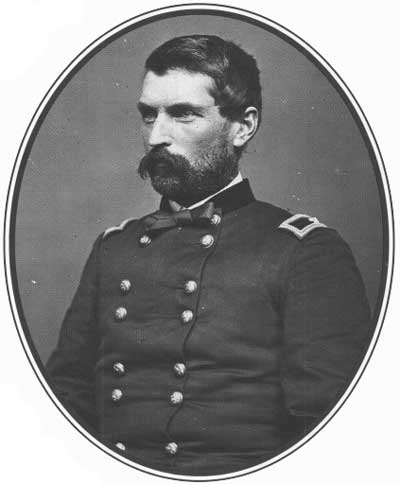

JOHN GIBBON (LC)

|

For some reason, neither Ewell nor Taliaferro moved the rest of their

nearby divisions into battle with the alacrity the situation required. A

frustrated Jackson found three Georgia regiments belonging to Alexander

R. Lawton's brigade and personally led them into line extending the left

of the Stonewall Brigade. Gibbon countered by summoning the Seventh

Wisconsin, which formed opposite Lawton's men on the right of the Second

Wisconsin. Jackson continued to ignore the chain of command and directly

ordered Trimble's brigade to move forward and protect Lawton's left.

Trimble encountered the last of Gibbon's regiments, the Sixth Wisconsin,

which anchored the expanding Union battle line now stretching about

one-half mile in length.