|

The scene that unfolded as darkness enveloped the Brawner farm

inspired eloquent descriptions by those who witnessed it. "Men standing

at arm's length ... giving and taking, life for life, each resolute and

determined, ceasing action only from sheer exhaustion, which was

complete upon one side as upon the other," remembered one Unionist.

Another Federal recalled that "the affair seemed to us like a mixture of

earthquake, volcano, thunder storm and cyclone. Even now we can hear

the . . . howls, growls, moans, screeches, screams and explosions. . . .

It might have been a tune for demons to dance to." A Confederate said

that "out in the sunlight, in the dying daylight, and under the stars,

they stood, and although they could not advance, they would not retire.

There was some discipline in this, but there was much more of true

valor."

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

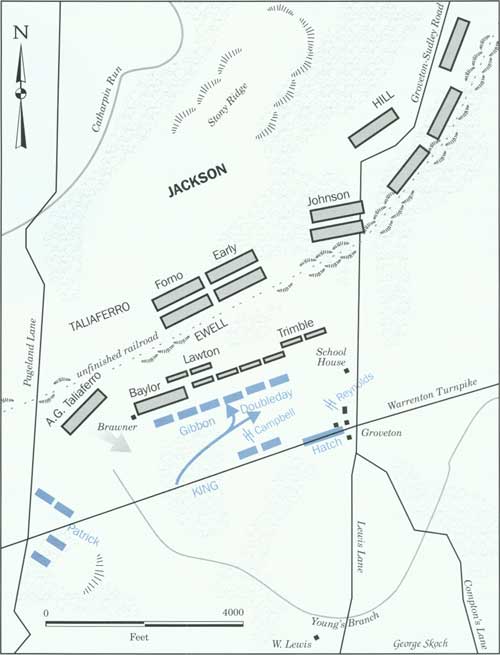

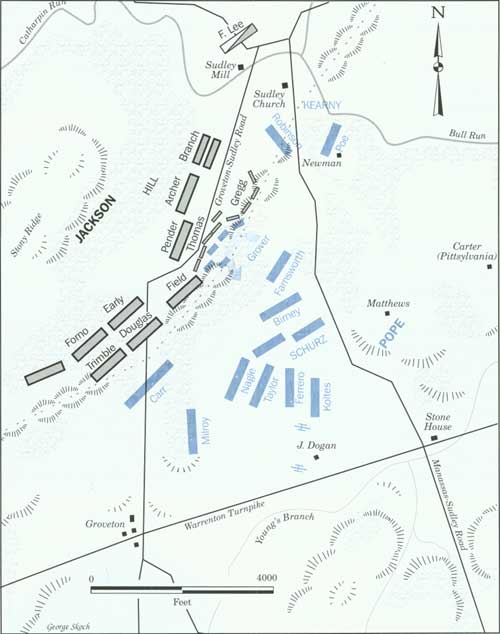

THE BATTLE OF BRAWNER FARM, AUGUST 28, 1862

After destroying Manassas Junction Jackson fell back to the old

battlefield of Manassas. Reuniting his troops along Stony Ridge, north

of the Warrenton Turnpike, they settled in to await the arrival of Lee

and Longstreet. But before they arrived, Jackson touched off the battle

on the afternoon of August 28, when the four brigades of King's Federal

division moved east along the turnpike to reunite with Pope in

Centreville. Jackson ordered his artillery to open fire on the enemy

column. John Gibbon sent his men to capture the guns, but after

advancing up the slope, they realized that they were facing several

brigades of Confederate infantry. As the two sides traded volleys 75

yards apart, Abner Doubleday, whose brigade had been following Gibbon's,

rushed up to help.

|

Trimble's appearance threatened to tilt the balance of power, so

Gibbon turned to Doubleday for assistance, That officer (who is often

incorrectly credited with inventing baseball) had anticipated Gibbon's

imperilment and advanced the Fifty-sixth Pennsylvania and the

Seventy-sixth New York to plug the gap between the Sixth and Seventh

Wisconsins. These men arrived after dark and aimed at their invisible

opponents by watching the muzzle flashes from Confederates muskets. Both

Trimble and Lawton launched uncoordinated attacks against the reinforced

Union battle line, receiving deadly repulses that cost one of Lawton's

regiments 72 percent casualties.

Darkness and confusion prevented Stonewall from employing the

additional brigades which had finally moved forward from Stony Ridge.

Confederate command incapacity increased when Ewell fell with a serious

wound while trying to lead an assault around the Union right flank.

Three Northern bullets found Taliaferro disabling him as well. But

Taliaferro's uncle, Alexander G. Taliaferro managed to advance three

regiments of his brigade from west of the Brawner house astride the

Nineteenth Indiana's axis of fire. Stuart's young cannoneer, John

Pelham, assisted Taliafero, pouring artillery projectiles into the

Hoosiers from less than 100 yards uprange.

At 9:00 P.M. Gibbon and Doubleday broke off the engagement and

withdrew to the turnpike in an orderly fashion, the Confederates too

exhausted to pursue. The Battle of Brawner Farm had ended in a hideous

tactical stalemate.

|

CURRIER AND IVES ILLUSTRATION DEPICTING THE SECOND BATTLE OF MANASSAS.

(LC)

|

The butcher's bill told a grim tale rarely duplicated during the

Civil War. Nearly one out of three battle participants fell killed or

wounded at the Brawner farm, a total of 1,150 Federals and 1,250

Confederates. "In this fight there was no maneuvering and very little

tactics," wrote William Taliaferro, "it was a question of endurance, and

both endured." Few honors belonged to the generals directing this

battle. Gibbon and Doubleday performed gallantly, but their invalided

division commander played no role and neither Hatch nor Patrick lent the

weight of their brigades to the equation. Jackson enjoyed a potentially

decisive numerical advantage but failed to employ all his troops,

because of in part the wounding of both Ewell and Taliaferro.

But if the tactical outcome at Brawner's farm left something to be

desired, Jackson could not have better achieved his strategic objective.

His attack on the evening of August 28 was the military equivalent of

waving a red flag under John Pope's nose—and the bullish Pope

reacted just as Stonewall had hoped. Rather than safely removing his

army to the far side of Bull Run, the Union commander called for a

concentration against Jackson at Groveton. He wrongly concluded that

Gibbon's fight at the Brawner farm had arrested Jackson's retreat from

Centreville and thus imagined another opportunity to demolish the Valley

magician. Pope issued a spate of orders on the night of the

twenty-eighth aimed at surrounding Jackson and attacking him in the

morning. Unfortunately, Pope predicated his strategy on several

erroneous premises.

|

WARTIME SKETCH OF THE BATTLE OF BRAWNER FARM BY EDWIN FORBES. (LC)

|

Pope assumed that McDowell and Sigel were west of Jackson blocking

his retreat route toward the Bull Run Mountains, but Reynolds's

division of McDowell's corps and Sigel's men were southeast of Stonewall

along the Manassas-Sudley Road. The rest of McDowell's command, King and

Ricketts, had already withdrawn from the turnpike before Pope's new

orders could reach them, convinced by captured Confederates that Jackson

had 60,000 troops ready to pounce on any nearby Federals at dawn. King

headed for Manassas and Ricketts for Bristoe Station after midnight.

McDowell could not bring order out of this strategic chaos because he

spent the night of August 28-29 wandering lost around Prince

William County in search of Pope and out of touch with his own division

commanders. Worst of all, Pope's presumption that Jackson was attempting

to retreat could not have been further from the truth. Stonewall was in

fact anxiously anticipating the new day when Longstreet would appear

and the Confederates would at last be reunited for battle. Incredibly,

Pope ignored the imminent arrival of this half of his opponent's

army.

Those soldiers, Longstreet's 25,000 men, began their march from

Thoroughfare Gap at 6:00 A.M. August 29. John Bell Hood, a sad-eyed

Kentuckian who had earned a brilliant combat reputation at the head of

Lee's only Texas troops, led the procession. Jackson dispatched Stuart a

couple of hours later to contact Hood and direct him and the rest of

Longstreet's wing into positions Stonewall had carefully

preselected.

In the meantime, Jackson shuffled his depleted divisions so that they

might withstand an attack should Pope became aggressive before Old Pete

could arrive. Jackson noticed a large number of Federals (Sigel's corps)

along the Manassas-Sudley Road in a position to threaten his left flank,

so he ordered Hill's brigades to file in behind the unfinished railroad

near Sudley Church with their left anchored on a rocky knoll. From here

Hill could guard the emergency escape route to Aldie Gap and protect

against a Federal turning movement. The thick green forest lapped

against the abandoned right-of-way in this vicinity, leaving the

Southern defenders particularly vulnerable to a surprise assault. Hill

compensated for this unavoidable weakness by arraying his brigades in

two lines, Maxcy Gregg's South Carolinians and Edward L. Thomas's

Georgians at the posts of honor in the front.

Ewell's wound at the Brawner farm required that his left leg be

amputated. Jackson's protégé would not return to active command until

the following spring, so Stonewall named Alexander Lawton to lead

Ewell's division. Lawton graduated from West Point in 1839 but resigned

his commission to attend Harvard Law School. The adopted Georgian

pursued a successful legal, business, and political career before his

state's secession induced him to rejoin the military. Jackson placed two

of Lawton's brigades in the center of his line and ordered the other

two, Jubal A. Early's and Henry Forno's, to move to the far right and

act as liaisons for Longstreet's units.

|

ILLUSTRATION BY EDWIN FORBES OF THE RETREATING UNION ARMY. (LC)

|

Porter, supported by King's division now under the command of John

Hatch, left Manassas on the road for Gainnesville to perform what Pope

anticipated would be the critical movement in the ruination of Stonewall

Jackson.

|

William E. Starke replaced the disabled Taliaferro in command of

Jackson's old division. Starke had been a cotton broker in New Orleans

at the outbreak of the war and had risen through the ranks to command a

Louisiana brigade. His eighteen regiments held Jackson's right where

expansive fields of fire and the ready-made shelter of the railroad

embankment made his position relatively strong. The most vulnerable

point along Starke's battle line lay on the extreme left, where his

division and Lawton's intersected. Here a 75-yard low point known as

"The Dump" offered little protection against attacking troops. Jackson

coldly ordered the skulkers and stragglers from several commands to

occupy this position as a practical object lesson in the virtue of

discipline. Stuart's cavalry patrolled both of Jackson's flanks, and

Stonewall unlimbered as much of his artillery as could obtain a field of

fire. The Confederate line stretched some 3,000 yards defended by about

20,000 graycoats.

Pope had every intention of testing Jackson's preparedness.

Disappointed to learn that King and Ricketts had abandoned the

Confederate front, Pope sent word to Fitz John Porter at Manassas to

attack King (Ricketts was temporarily out of the picture at Bristoe) and

move north toward Gainesville to regain a blocking position beyond

Jackson's right. Porter received these orders after daylight while lying

on his headquarters cot elegantly draped by an imitation leopard-skin

blanket. By 10:00 A.M. Porter, supported by King's division now under

the command of John Hatch, left Manassas on the road for Gainesville to

perform what Pope anticipated would be the critical movement in the

ruination of Stonewall Jackson.

|

PUSHING ASIDE A TOKEN FEDERAL FORCE THE NIGHT BEFORE AT THOROUGHFARE

GAP, LONGSTREET'S MEN MARCHED TO THE ASSISTANCE OF JACKSON, ALREADY

ENGAGED AGAINST POPE'S FORCES. (BL)

|

In the meantime, Sigel and Reynolds responded to Pope's directives to

attack Jackson at daybreak. These Federals, less than 12,000 strong, had

only the vaguest notion of how Jackson had deployed. Sigel therefore

opted to approach the Confederates along a broad front. Robert C.

"Fighting Bob" Schenck's division supported by Reynolds would move west

on the turnpike and form Sigel's left. Robert H. Milroy's Independent

Brigade assumed responsibility for the center, and Carl Schurz's

division advanced north on the Manassas-Sudley Road on Sigel's right.

Schurz's men found Jackson first about 7:00 A.M.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

SIGEL'S ATTACK LATE MORNING, AUGUST 19, 1862

After the fight at Brawner farm, Jackson aligned his troops behind

the unfinished railroad on a front 3,000 yards long. On the morning of

August 29, Federal forces began massing along Jackson's front. With

orders to attack the enemy vigorously at daylight, Franz Sigel's corps

advanced against the Confederate line only to be repulsed with heavy

losses.

|

A Union officer described Schurz as "a pale, wide-foreheaded,

red-mustached, spectacled, effeminate-looking German. He had sharp,

hazel eyes, was thin and tall, the very pattern of a visionary, itching

philanthropist and philosopher such as disturb society everywhere with

their restless conceits and babblings." This unflattering portrait

failed to do justice to one of America's leading orators and

abolitionists. Like Sigel, Schurz owed his high military stature to his

ethnicity and political influence, but unlike his superior, Schurz

possessed some martial ability.

Schurz's two brigades skirmished heavily with Gregg and Thomas, each

side committing its regiments piecemeal in the matted woods south of the

unfinished railroad. "The rattling fire of skirmishers changes into

crashes of musketry, regular volleys, rapidly following each other,"

remembered Schurz. Hill's troops blunted the Federal advance, although

the Confederates were unable to exploit their advantage in the trackless

terrain.

Milroy heard the sharp report of combat to his right and blindly

ordered two of his regiments to move to Schurz's assistance. These

troops ran into Lawton's division along the Groveton-Sudley Road and

received a costly repulse, although a part of the Eighty-second Ohio

briefly breached the Confederate line near The Dump. Farther to the

southwest, Schenck and Reynolds fell under an intense artillery barrage

and deployed in the woods around Groveton replying with counterbattery

fire but choosing not to commit their infantry.

Sigel's offensive lasted until 10:00 A.M. without altering the

strategic equation. Phil Kearny's division promised to terminate this

impasse when it moved up opposite the left end of Hill's combat-weary

line. In anticipation of receiving support from Kearny, Schurz once

again lunged toward Hill's waiting brigades. The usually reliable New

Jerseyian, however, failed to advance, possibly indulging a bitter

grudge he nurtured against Sigel. Kearny's inaction squandered the

temporary toehold won by Schurz along the unfinished railroad, and once

again a Confederate counterattack drove the Yankees back through the

woods. "The men still in the ranks . . . well-nigh reached the point of

utter exhaustion," confessed Schurz, and by midday his battle had

ended.

Sigel's efforts that morning had not been entirely in vain. He had

located Jackson and "brought [him] to a stand," thought Pope, while

Porter and Hatch marched toward what the Union commander considered the

key point on the map. In addition to Kearny, Hooker's division and Isaac

I. Stevens's brigades of Reno's corps arrived to reinforce Sigel. At

1:00 P.M. Pope appeared on the battlefield expecting that the afternoon

would witness his long-deferred victory.

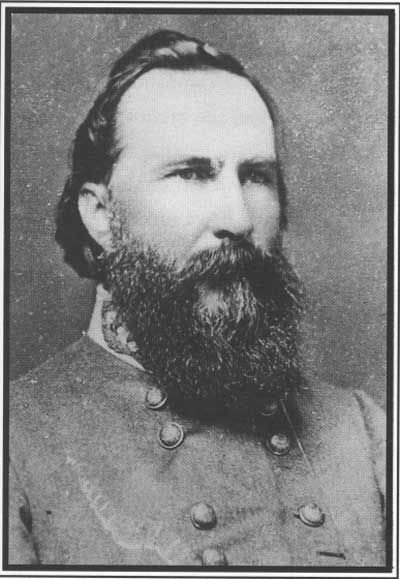

But as usual, John Pope forgot about Longstreet. Old Pete, in the

company of General Lee, met with Jackson in mid-morning near the Brawner

farm while Hill's brigades engaged their Federal opponents to the east.

Stonewall outlined the location of his wing and, with apparent approval,

the positions he recommended for Longstreet's divisions. Shortly

thereafter Hood's veterans swung into view and deployed astride the

turnpike facing east, loosely linking with Jackson's right flank.

|

POSTWAR VIEW OF TRE BATTLEFIELD NEAR GROVETON. (LC)

|

James L. Kemper, a Virginia political general, filed in on Hood's

right south of the turnpike. David R. "Neighbor" Jones, a

thirty-seven-year-old South Carolinian, placed his division on

Longstreet's right, unknowingly blocking Porter's approaching column.

Cadmus Marcellus Wilcox arrived last and served as Longstreet's reserve

along Pageland Lane south of the turnpike. Nineteen guns dropped trail

on a ridge northeast of the Brawner farm, strengthening Longstreet's

connection with Jackson. By noon the Confederates completed their

arrangements. The gray line extended three miles facing east and

southeast—a huge pincers aimed at Pope's left flank. Lee, Jackson,

and Longstreet had completed an improbable maneuver begun more than four

days earlier. Now they sought to exploit the opportunity earned by their

risk-filled march.

Well before Longstreet had emplaced his divisions, a handful of

Stuart's cavalry blundered into Porter, Hatch, and McDowell, who were,

in accordance with their morning orders, moving north on the

Gainesville-Manassas Road. The scattered shots exchanged between a

Pennsylvania regiment and the Confederate horsemen succeeded in halting

the Union column. Porter now turned to receive a mounted courier bearing

a message from Pope that would prove to be one of the most controversial

documents of the campaign.

This communique became known as the "Joint Order," and Pope had

written it from Centreville about 10:00 A.M. Directed to both McDowell

and Porter, it reassigned Hatch's division to McDowell and attempted to

clarify the goal of the movement toward Gainesville. But Pope employed

such cautious and qualifying language in his directive that the Joint

Order resulted in precisely the opposite of what he later professed to

intend.

Apparently, Pope envisioned the scattered elements of his army

converging simultaneously to challenge Jackson in his front and isolate

him from Thoroughfare Gap. Sigel, Heintzelman, Reno, and Reynolds would

maneuver west along the turnpike and develop Jackson's location, an

operation that had already resulted in Sigel's morning combat. McDowell

and Porter would reach the turnpike near Gainesville, connect with the

rest of the army to the east, and strike Jackson on his supposedly

vulnerable right flank.

Unfortunately for the Federals, the Joint Order as written did not

convey this conception. Instead it instructed McDowell

and Porter to move toward (not to) Gainesville and "as soon as

communication is established [with the other divisions] the whole

command shall halt. It may be necessary to fall back behind Bull Run to

Centreville tonight." After reiterating the possible need to retreat,

Pope concluded by telling his two subordinates that "if any considerable

advantages are to be gained from departing from this order it will not

be strictly carried out." Nowhere did the Joint Order explicitly direct

Porter and McDowell to attack.

|

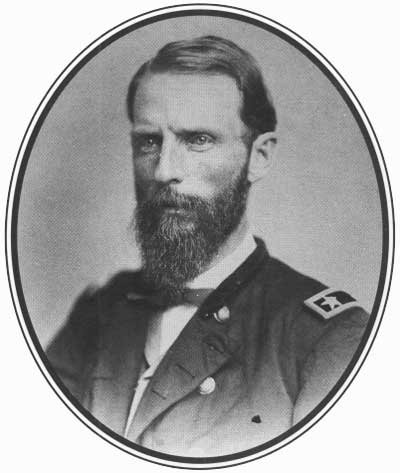

JAMES LONGSTREET (USAMHI)

|

|

POSTWAR VIEW OF THE GROUND LONGSTREET'S MEN OCCUPIED ON AUGUST 29. (LC)

|

While the two Federal generals digested the import and meaning of

Pope's instructions, they noticed clouds of dust along the horizon on

Porter's front. Jeb Stuart had decided to delay the oncoming Union

column with clever theatrics until Longstreet could complete his

deployment. He told one of his officers to collect a supply of branches

and assign a regiment to drag the limbs across the road, creating the

appearance of an approaching multitude. This stratagem worked perfectly,

especially when McDowell received a report from his cavalry commander,

John Buford, who had counted "seventeen regiments of infantry, one

battery, and five hundred cavalry" moving through Gainesville at 8:15

that morning. Buford, of course, had discovered Longstreet's wing moving

from Thoroughfare Gap, and, combined with Stuart's dusty disturbance,

Buford's warning convinced Porter and McDowell that trouble loomed

ahead. Mindful of Pope's requirement that they be prepared to retreat

that night and the Joint Order's clause permitting discretion, McDowell

and Porter made decisions completely at odds with Pope's actual, if

unarticulated, thinking.

McDowell told Porter that "you are too far out already; this is no

place to fight a battle." Exercising his regained independence from the

Fifth Corps commander, McDowell ordered Hatch and Ricketts, on the march

from Bristoe, to shift to the northeast, gain the Manassas-Sudley Road,

and then move north to the turnpike. From there McDowell would turn

westward toward the army's left and reestablish communication with

Porter. Porter simply shook out a strong line of skirmishers, readied

his artillery, and rested his men, awaiting clarification of the

situation from Pope, McDowell, or others, while maintaining a watchful

eye for Confederate activity in his front.

|

THE SUDLEY-MANASSAS ROAD LOOKING NORTH TOWARD THE WARRENTON TURNPIKE.

(LC)

|

Porter and McDowell knew full well that Longstreet had arrived

opposite Porter's line of march and that Pope's Joint Order, confidently

advising that Longstreet was still thirty-six to forty-eight hours away,

was painfully in error. But for some inexplicable reason McDowell failed

to forward Buford's report to Pope, so the Union commander remained

aggressively unaware of Porter's dilemma. Moreover, Pope believed that

the Joint Order would initiate a decisive offensive by Porter and

McDowell. Thus he would base his afternoon strategy around these two

egregious misconceptions.

Meanwhile, Lee and Longstreet struggled with dispersing their own fog

of war. Once Longstreet's divisions reached their assigned positions,

Lee immediately sought to assume the offensive against the Federal left.

Longstreet however, demurred and suggested an investigation of the Union

deployment both along the turnpike and south of Gainesville. Lee agreed,

and in an hour Old Pete returned with worrisome news. The Federal line

(Reynolds and Schenck) extended south of the turnpike covering about

half of Longstreet's front. These Yankees would offer substantial if not

insurmountable resistance to a Confederate attack. The bluecoats on the

Gainesville-Manassas Road (Porter) must also be neutralized, thought

Longstreet, or he would risk their intervention on his right flank and

rear during any attack eastward on the turnpike. The time, Longstreet

insisted, was not right for his wing to move forward.

Lee strenuously dissented and offered other expedients to Longstreet,

who steadfastly clung to his conclusion. Marse Robert authorized his

engineers to reexamine the ground, but before they could depart Stuart

reported that the Union force on the Gainesville-Manassas Road did

indeed present a formidable threat. This ended the Lee-Longstreet

debate for the moment. There would be no attack until Lee could learn

more about those Federals. Thus Porter's mere presence undercut

Longstreet's offensive capabilities on the afternoon of August 29, but

John Pope expected more of the Fifth Corps than that—much more.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

GROVER'S ATTACK, 3:00 P.M., AUGUST 29, 1862

With 1,500 men Cuvier Grover advanced against the Confederate line.

Quickly Grover's men stormed over the top of the railroad embankment and

proceeded to shatter the Confederate position. With no support, Grover's

attack faltered. The brigade soon fell back to where it had started,

leaving behind 487 men killed, wounded, and missing.

|

Pope, of course, predicated the rest of his day's battle plans on his

anticipation of Porter's pivotal assault against Stonewall Jackson's

"exposed" right flank, a delusion of the first magnitude. Pope would

authorize four separate offensives against Jackson's front for the sole

purpose of occupying Stonewall's attention until Porter delivered his

fatal blow. Despite the hollow premise of this strategy, Pope's

afternoon offensives on August 29 severely tested Jackson's hard-pressed

divisions.

Shortly after midday, Pope instructed Stevens and Hooker to relieve

the exhausted Schurz on the Union right. These officers obeyed, but

Schurz's withdrawal permitted Edward Thomas to plant the Confederate

banner along the railroad cut in his front. Thomas, however, allowed a

125-yard gap to open between his regiments and Gregg's, a significant

oversight that would soon threaten the viability of the Confederate

line.

Cuvier Grover's brigade of Hooker's division struck that gap about

3:00 P.M. in the first of Pope's afternoon attacks. This young New

Englander commanded five regiments, only 1,500 men, but expected to

receive support from Kearny's division. Wishing to avoid the open ground

in his immediate front and to form a connection with Kearny's brigades,

Grover angled his unit toward the right. Although Kearny failed to

advance once again, Grover's course brought him, purely by accident, to

the gap between Thomas and Gregg.

With bayonets fixed along a battlefront one-quarter mile wide,

Grover's determined warriors charged with a yell, rapidly reaching

Thomas's startled defenders.

|

With bayonets fixed along a battle-front one-quarter mile wide,

Grover's determined warriors charged with a yell, rapidly reaching

Thomas's startled defenders. "I was within two rods of the enemy's line

before I was aware of it," admitted a Massachusetts volunteer. A soldier

in the Forty-fifth Georgia recalled that "I turned and saw the whole

regiment getting away, and I followed the example in tripple

[sic] quick time." In a matter of moments, Grover had overrun

Thomas and isolated Gregg. This was the time when fresh Union troops

might have effected the permanent dislocation of Jackson's left

flank.

But Pope never intended to devote his major effort to this end of the

battlefield. Grover's success represented a mere diversion, although

Kearny's nonparticipation contributed to the certainty that Grover's

gains would be temporary. Gregg responded to the crisis on his right by

committing three regiments to assail Grover's exposed flank. North

Carolinians under Dorsey Pender appeared from Hill's reserve line to

press Grover in front. "The effect was terrible," shuddered a soldier

from the First Massachusetts. "Men dropped in scores, writhing and

trying to crawl back, or lying immovable and stone-dead where they

fell." Within 30 minutes of their advance, Grover's men returned to

their jump-off points, leaving behind one-third of their comrades

killed, wounded, or captured.

|

CUVIER GROVER (USAMHI)

|

Pope ordered John Reynolds to conduct the next spoiling attack south

of the turnpike. Reynolds, who had watched Longstreet's wing deploy late

in the morning, reported that a large Confederate force menaced his

front but dutifully obeyed his superior's command. Predictably, Reynolds

encountered Longstreet's extensive lines almost immediately. He promptly

canceled his demonstration, reiterating to Pope the reality of the

situation. The Union commander dismissed Reynolds's concern as a case of

mistaken identity, absurdly insisting that the Pennsylvanian had

actually seen Porter's divisions preparing for their imminent attack

against Jackson's flank.

In the meantime, Jesse Reno complied with Pope's order to occupy the

Rebels in his sector by advancing a brigade under James Nagle. Nagle's

experience mirrored that of Grover an hour earlier. His three large

regiments pierced the Confederate center near the Groveton-Sudley Road

and swept Trimble's brigade from the railroad embankment. But without

supports, Nagle fell victim to a Confederate counterattack led by a

Marylander named Bradley Johnson. Johnson landed on Nagle's left flank

and, assisted by a fresh brigade of Louisianians, drove Nagle back from

whence he came. The Confederates pursued into the open fields where

Union artillery halted their advance. During this charge a Virginian in

Johnson's brigade remembered hearing "a thud on my right, as if one had

been struck with a heavy fist. Looking around, I saw a man at my side

who was standing erect, with his head off and a stream of blood spurting

a foot or more from his neck." Three other Confederates had been killed

by this same cannon ball.

|

1880s VIEW OF HENRY HILL, SITE OF THE CLOSING ACTION DURING THE BATTLE.

(LC)

|

Pope now consolidated his lines, placed McDowell's newly arrived

divisions of Hatch and Ricketts on Henry Hill in support of the

justifiably nervous Reynolds, and sent positive orders to Porter to

begin his attack. "Your line of march brings you on the enemy's right

flank. I desire you to push forward into action at once on the enemy's

flank, and, if possible, on his rear, keeping your right in

communication with General Reynolds." Pope wrote this directive at 4:30

P.M. but his aide, Pope's nephew, lost his way and did not deliver the

message until two hours later. Of course, Pope's instructions were no

less impractical in the evening than they were in the afternoon and

Porter could not execute them.

It would be several more hours, however, before the sanguine Union

commander would realize this. Expecting Porter's long-anticipated

offensive at last to be imminent, Pope renewed his order to Kearny to

assail Jackson's far left, providing what Pope thought would be

simultaneous pressure against both Confederate flanks. Kearny assembled

ten regiments, some 2,700 men from three of his brigades, and prepared

to move both astride the unfinished railroad and against Jackson's

front, employing support from twenty pieces of artillery.

|

|