Porter struggled with the wooded terrain east of Groveton and

required nearly two hours to arrange his 10,000 troops for the assault.

Henry Weeks and Charles Roberts placed their brigades on the left and in

the center of Porter's formation. Hatch's division assumed

responsibility for Porter's right. Two brigades of regular United States

Army troops under George Sykes filed into a reserve line poised to

exploit any local advantage earned by the initial attackers. On his own

initiative after Reynolds's departure, Gouverneur K. Warren shifted his

tiny brigade of two New York regiments to a position south of the

turnpike. Warren joined Battery D of the Fifth United States Artillery

under young Charles Hazlett, who had emplaced his six guns on a

prominent knoll overlooking Groveton. Only a handful of additional Union

artillery could find locations from which to strengthen the infantry

attack. Porter's foot soldiers would have to carry the burden virtually

alone.

The Confederates targeted by Porter's assault belonged to Starke's

division, which formed in parallel lines concealed by the unfinished

railroad and the woods beyond. Louisiana planter Leroy A. Stafford

commanded Starke's old brigade of Bayou Staters who defended the line

near The Dump. To Stafford's right, Bradley Johnson's Virginians

occupied a pronounced portion of the railroad bed known as the Deep Cut.

Brawner farm veterans from A. G. Taliaferro's command and the Stonewall

Brigade crouched in the forest on Johnson's right. A Maryland battery

provided direct support to the Confederate battle line, which fronted an

open field varying in depth from 300 to 600 yards, the last 150 yards of

which pitched sharply uphill.

At 2:30 P.M. members of Hiram Berdan's colorful Union sharpshooters

scaled the fence along the Groveton-Sudley Road and entered the pasture

owned by a widow named Lucinda Dogan, whose substantial holdings

surrounded the village of Groveton. Joined by two New York regiments,

the green-uniformed marksmen found slight shelter in a dry streambed

(now called Schoolhouse Branch) and skirmished with Starke's

Confederates for nearly thirty minutes. Then Porter's lead ranks emerged

from the woods and began their long trek across the killing fields of

the Dogan farm.

Hatch's men on the Union right faced the shortest exposure in the

open ground. The soldiers of the Twenty-fourth and Thirtieth New York

toppled the fence paralleling the road and hastened for the Confederate

positions under an intense fire from cannon and muskets. "The shouts and

yells from both sides were indescribably savage," remembered one New

Yorker. "It seemed like the popular idea of pandemonium made real, and .

. . it is scarcely too much to say that we were really transformed for

the time, from a lot of good-natured boys to the most blood-thirsty of

demoniacs."

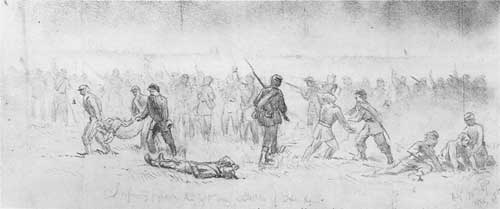

|

SKETCH OF PORTER'S ATTACK AS SEEN FROM HENRY HILL. (LC)

|

The Federals managed to reach the edge of the railroad bed separated

from their gray-clad opponents by the width of the embankment. Several

particularly brave Union officers entered the fight on horseback,

making themselves conspicuous targets and attracting grudging

admiration from nearby Confederates. After a momentary debate, the

Southerners decided that this Yankee gallantry did not warrant a

reprieve from the hazards of war, and Rebel rifles tumbled the

courageous New Yorkers from their saddles. The surviving Federals

clutched the ground below the embankment and formed a rough line within

whispering distance of the Louisianians.

To Hatch's left, Roberts and Weeks appeared on the naked tract

opposite Bradley Johnson's waiting Virginians. "The advance began in

magnificent style, lines as straight as an arrow, all fringed with

glittering bayonets and fluttering with flags," wrote a Confederate

observer. "But the march had scarce begun when little puffs of smoke

appeared, dotting the field in rapid succession just over the heads of

the men, and as the lines moved on, where each little puff had been, lay

a pile of bodies, and half a dozen or more staggering figures standing

around leaning on their muskets and then slowly limping back to the

rear." These Unionists had to traverse nearly a quarter-mile of

shelterless terrain before gaining the unfinished railroad, and they

paid dearly for the achievement. As they reached Johnson's position, the

Confederates leveled their rifles and unleashed a withering volley. "The

first line of the attacking column looked as if it had been struck by a

blast from a tempest, and had been blown away," marveled one

Southerner.

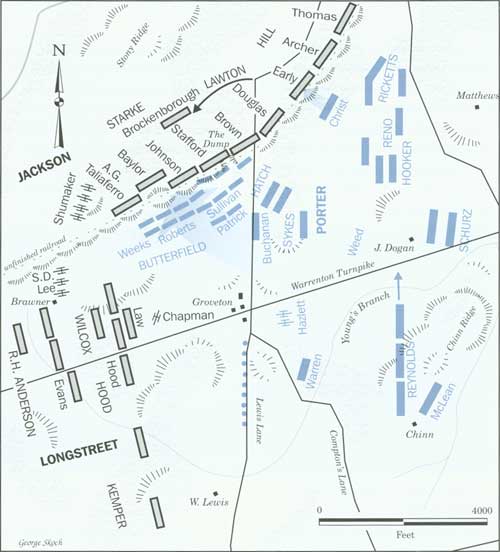

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

PORTER'S ATTACK, 3:00 P. M. AUGUST 30, 1862

Like an avalanche the men of Porter's corps descended into the fields of the

Dogan farm. Hatch's brigade on the Union right faced the shortest

stretch of exposed ground and quickly reached the railroad embankment,

only to be pinned down. Butterfield's division on the Union left had the

farthest distance to cover in order to reach the Confederate line. The

Union ranks on the left were constantly raked by S. D. Lee's guns on the

heights north of the Brawner farm. With their ammunition running low,

some Confederates along the unfinished railroad were reduced to fighting

with rocks. As Southern reinforcements arrived on the front, Porter's

men fell back from the railroad, their attack in shambles.

|

But the Federal momentum penetrated Johnson's line, routing the

Forty-eighth Virginia and compromising the rest of the unit. In rushed

the Stonewall Brigade led by its intrepid commander, William S. H.

Baylor. The Valley veterans restored the Confederate battlefront at

heavy cost, including Colonel Baylor, who died with the flag of the

Thirty-third Virginia wrapped around his body. As was the case on

Hatch's sector, the Federals near the Deep Cut retained their advanced

positions exchanging a ceaseless fire with their well-sheltered

opponents behind the railroad excavation just a few yards away.

|

ROBERT E. LEE AND HIS STAFF ON THE BATTLEFIELD AT MANASSAS. (LC)

|

|

S. D. LEE'S WELL-PLACED ARTILLERY DECIMATED THE RANKS OF PORTER'S CORPS.

(LC)

|

Jackson clearly needed help. Stonewall's three divisions had marched

more than fifty miles in thirty-four hours, destroyed the Union supply

base, fought delaying actions at Bristoe and Manassas, engaged Pope's

army at the Brawner farm, and fought along Stony Ridge for two days. His

bloodied and battered brigades had thus far carried the campaign

virtually alone, and the time had come for Longstreet to contribute.

Jackson dispatched the future memoirist Henry Kyd Douglas to ask Old

Pete for assistance.

Longstreet also recognized that the moment had arrived for his

divisions to uncoil. But he reasoned that sending infantry to Jackson

would consume too much time. Instead he ordered additional batteries to

drop trail in support of S. D. Lee's guns at the Brawner farm. These

artillerists enjoyed an unobstructed view of the pastureland across

which any Union reinforcements must move to reach their comrades huddled

along the embankment. This same fire would inflict appalling casualties

on any Northerners who attempted to retreat from their toeholds to the

safety of the Groveton Woods. Within twenty minutes of the commencement

of Porter's attack, the ground between the Groveton-Sudley Road and the

unfinished railroad exploded from the effect of Lee's cannonade.

When fresh Union troops attempted to run this gauntlet, iron missiles

from Confederate guns cut them to pieces. "Longstreet's batteries . . .

were enfilading the approaching troops with solid shot, shell, and

sections . . . of railroad iron, which tore up the earth frightfully,

and was death to any living thing that they might touch on their

passage." Porter opted not to commit Sykes to the relief of Roberts and

Weeks, but he did allow additional units from Hatch's division to

attempt to rescue the two regiments clinging to the unfinished railroad

on the Union right. As these Federals raced across the fields absorbing

a brutal enfilading artillery fire, they encountered the cataclysmic

presence of fresh Confederate infantry released by Lawton's division to

support Stafford's hard-pressed left flank. "They were so thick it was

just impossible to miss them," said one Southerner. "What a slaughter of

men that was."

By this time, Porter had surrendered the initiative. He chose not to

reinforce failure any longer and essentially abandoned to their fates

the four Union brigades who had clawed their way to the front. Had he

known, however, how severely his assaults had stressed Jackson's line,

he might have continued the offensive. Stafford's and Johnson's brigades

had completely expended their ammunition and relied on hurling large

rocks across the embankment to defend their position. The rest of

Stonewall's wing had nearly reached its capacity to sustain combat. But

the appearance of Charles Field's Virginia brigade of A. P. Hill's

division ultimately tipped the balance in favor of the Confederates. "At

last physical strength and moral endurance alike gave way before the

terrible effect of our fire," boasted a Rebel officer, "and the whole

[Union] force fled in disorderly rout to the rear."

|

UNION TROOPS OF PORTER'S CORPS FELL LIKE TENPINS BEFORE AN EXPERT

PLAYER. (LC)

|

|

SOLDIERS OF PORTER'S CORPS CHARGED FORWARD AGAINST JACKSON'S LINE. THE

CONFEDERATES, PROTECTED BY THE UNFINISHED RAILROAD, SHATTERED THIS

ATTACK IN LESS THAN THIRTY MINUTES. (LC)

|

Porter's advanced brigades lost heavily during their retreat from the

unfinished railroad. Some of Starke's men, caught up in the passion of

victory, began a spontaneous pursuit that met a decided repulse from

Union reserves posted along the Groveton-Sudley Road. The Confederates

returned to their original positions and witnessed an unspeakable scene

of horror. "The Yankees in front of the RR . . . were lying in heaps,"

recalled a Louisianian, "Some with their brains oozing out; some with

the face shot off; others with their bowels protruding; others with

shattered limbs."

The survivors of Porter's attack found welcome refuge in the Groveton

Woods east of the Groveton-Sudley Road. Sigel's corps, Milroy's brigade,

and Federal cavalry units supported Sykes and the reserve regiments of

Hatch's division to stem the tide of refugees. Jackson's exhaustion

rendered him unable to organize a rapid pursuit, allowing Porter to

stabilize the tactical situation north of the turnpike. But to Irvin

McDowell the situation appeared grim. Fearing for the safety of Porter's

corps, McDowell ordered Reynolds to cross the turnpike from Chinn Ridge.

Not only was such a precaution totally unnecessary but Reynolds's

departure left only 2,200 men south of the highway, McLean's and

Warren's brigades, to oppose more than ten times that many Confederates.

McDowell's decision would be the most serious tactical error of the day

because those Confederates were about to erupt onto the tactical stage

at Second Manassas with dramatic effect.

Lee and Longstreet both concluded that the moment had indisputably

arrived to commence the massive Confederate offensive that Lee had hoped

to begin the previous day. Its goal, ironically, would be Henry Hill,

the key terrain at the First Battle of Manassas. Confederate control of

this lofty plateau would confine the Federals to the north side of the

turnpike and deny them their retreat routes across Bull Run. The lure of

complete victory thus animated Longstreet's five divisions, whose enemy

would be the descending sun as well as the Northern army.

Longstreet's wing extended nearly a mile and a half from the Brawner

farm on its left to the Manassas Gap Railroad on its right. The distance

to Henry Hill varied from one and a half to two miles and the

intervening landscape contained numerous small streams, some heavy

woods, and intermediate ridges. Old Pete recognized that his troops

would find it impossible to maintain an unbroken attack formation so

success would depend on speed, good judgment, and hard fighting by his

individual subordinate commanders. John Bell Hood's division, led by the

Texas Brigade and supported by Nathan G. "Shanks" Evans's South

Carolinians, would begin the assault from the left of Longstreet's line,

nearest the turnpike. Kemper's division would move on Hood's right with

D. R. Jones's brigades in support of Kemper's right. The rest of

Longstreet's wing would provide a ready reserve. "The heavy fumes of

gunpowder hanging about our ranks, as stimulating as sparkling wine,

charged the atmosphere with the light and splendor of battle," recalled

Longstreet, and "as the orders were given ... twenty-five thousand

braves moved in line as by a single impulse."

At 4:00 P.M. Hood's five regiments (only three of them Texans)

stepped out "with all the steadiness and firmness that characterizes

war-worn veterans." Their first opposition would come from the Tenth and

Fifth New York regiments, Warren's 1,000 men deployed in skirmish

formation along Lewis Lane (the southern extension of the

Groverton-Sudley Road) and on a partially wooded ridge to the east.

Hood's soldiers "yelling all the while like madmen," easily brushed aside

the six companies holding Lewis Lane and swept forward against Warren's

main position.

In a matter of moments the rest of Warren's brigade disintegrated.

"The only hope of saving a man was to fly . . . for in three minutes

more there would not have been a man standing," reported a participant.

The Fifth New York, a proud unit that would produce eight generals from

its ranks, suffered more men killed in ten minutes than any other

regiment would lose in a single battle during the entire Civil War. A

witness compared the aftermath of this fight to a "posy garden,"

referring to the corpses of the Fifth New York in their gaudy Zoauve

uniforms. Hazlett's battery fired as long as it could then departed with

remarkable discipline.

|

WITH THEIR AMMUNITION EXHAUSTED, CONFEDERATES ALONG THE UNFINISHED

RAILROAD HURLED ROCKS AT THE ATTACKING FEDERAL SOLDIERS. (LC)

|

|

THE MEN OF THE FIFTH NEW YORK TRIED IN VAIN TO HALT THE TEXANS OF JOHN

BELL HOOD'S BRIGADE. (NPS ILLUSTRATION BY ANTHONY RANFON.)

|

Pope and McDowell now began to understand the magnitude and

consequence of their mistaken strategic analysis and took immediate

steps to salvage the battle and save their army. Orders went out to

occupy Henry Hill, undeniably the right move but an endeavor that would

consume considerable time. The Ohioans of Nathaniel McLean's brigade

with whatever reinforcements Pope could quickly muster would bear the

awful responsibility of purchasing that time.

McLean, the distinguished son of a congressman and Supreme Court

justice, aligned his four regiments facing west on the narrow open crest

of Chinn Ridge, about one-half mile east of where Warren met disaster. A

battery of artillery unlimbered in the center of McLean's 1,200 men, who

girded themselves to receive Hood's impending assault. "As soon as our

retreating troops got out of the way, I opened upon the enemy with my

artillery and as they came nearer, with a heavy fire from my infantry,"

reported McLean. Combined with a barrage launched from Federal guns

north of the turnpike, McLean's fusillade "drove them back more rapidly

than they had advanced."

Now Hood summoned Evans's troops to recapture the temporarily stalled

Confederate momentum. Evans shifted his regiments toward the south and

charged up the slope of Chinn Ridge against the Federals' left flank.

But McLean responded by redeploying two of his units to the point of

danger and Evans receded into a patch of piney woods to regroup. The

Union line had held, at least until the next Rebel onslaught.

That threat would come from the dark-uniformed Virginia brigade of

Montgomery Corse, a portion of Kemper's division. Corse, a

forty-six-year-old banker and former militia officer from nearby

Alexandria, wheeled his regiments into line nearly at right angles to

Evans, facing north rather than east. As Corse's Confederates approached

the Buckeyes, the Ohioans initially mistook them for friends, allowing

the Virginians to close the distance without opposition. Soon enough,

however, the Unionists corrected their error and unleashed a crashing

volley from behind a rail fence near the Chinn house. A soldier in the

Seventeenth Virginia reported that the Northern blast "came upon us with

the suddenness of a thunderbolt. We all sprang forward with one ringing

yell—the officers waving their swords and the men standing still

only long enough to fire off their guns." The ensuing battle raged for

ten minutes at point-blank range, but when a Louisiana artillery

battery added its voice to Corse's determined attackers, McLean's line

at last collapsed. The Ohioans suffered 33 percent casualties but with

their blood earned Pope thirty precious minutes to rush reinforcements

to Chinn Ridge.

|

"OH THIS IS A DREADFUL WAR"

Alfred Davenport was a member of the Fifth New York Infantry. On the

afternoon of August 30, his regiment would suffer the highest number

killed and mortally wounded of any Union regiment during the Second

Battle of Manassas. He described the destruction of his unit in a letter

to his father on September 3, 1862.

"It was not long before a company of the skirmishers came in on our

left all much excited, huddled together in a heap and much scared and

said that the enemy were coming in and were right on top of us, on the

left flank, but before any orders could be given to change position, the

balls began to fly from the woods like hail. It was a continual hiss,

snap, whizz and slug.

Private Brady, who used to live opposite us in Newington Avenue, in

the wooden house was the first one hit—he stood a few files from

me. He fell without saying a word, struck in the body. . . . Only the

companies on the left could fire. We commenced, but the Rebels' fire

was now murderous, our men falling on all sides.

The order had been given to retreat and save ourselves, every man

for himself, but we did not here the order. The recruits began to give

way and then the whole regiment, broke and ran for their lives. . . .

There was no hope but in flight.

While running down the hill towards the small stream at its foot, I

saw the men dropping on all sides, canteens struck and flying to

pieces, haversacks cut off, rifles knocked to pieces, it was a perfect

hail of bullets. I was expecting to get it every second, but on, on, I

went, the balls hissing by my head.

How I escaped I don't know but I thank God for it. There are now only

eight or ten two-year men left in our company who were at Fort Schuyler

when the regiment was first formed. We had then 101 men in our company

and I can hardly expect to survive another such engagement; if we should

be unfortunate enough to get into another, it will wipe us out as a

thing of the past. Oh this is a dreadful war!"

Davenport survived the war and went on to author the history of his

regiment published in 1879. He died in 1899 in his native New York.

—Chris Bryce

|

DESTRUCTION OF THE FIFTH NEW YORK BY HOOD'S TEXAS BRIGADE. (LC)

|

|

The first of these troops belonged to Zealous B. Tower's brigade of

Ricketts's division. Galloping up beside Tower came the Fifth Battery of

Maine Light Artillery under George Leppien. "The confusion among the

troops on the hill was great," admitted one Unionist. "Officers and men

shouting, shells tearing through and exploding, the incessant rattle of

muskets, the cries of the wounded—all combined made up a scene that

was anything but encouraging." Despite the chaos, most of Tower's units

efficiently deployed, facing south toward the Chinn house some 300 yards

away as Leppien's guns roared into action. Now the focus of fighting

revolved around Leppien's battery as Hood, Evans, and Corse converged

from three sides on the desperate Union resistance. "Nothing could be

seen but the flash of the guns," remembered a Confederate as the battle

lines melted into a caldron of death in the center of Chinn Ridge.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

THE FIGHT FOR CHINN RIDGE, 1:00 P.M. AUGUST 30, 1862

Shortly after the repulse of Porter's attack, Longstreet ordered his

men toward the left and rear of Pope's army. Rushing to Chinn Ridge the

Federal brigades of McLean, Tower, and Stiles stalled the Confederates,

enabling Pope's army to establish a final line of defense on the slopes

of Henry Hill.

|

Some of Corse's regiments had worked their way into the shallow

valley of Chinn Branch, east of where Tower and Leppien conducted their

defense. Their fire against Tower's unprotected left flank when combined

with unrelenting pressure against the Federal right and front eventually

determined the outcome. "There was a frenzied struggle in the

semi-darkness around the guns, so violent and tempestuous, so mad and

brain-reeling that to recall it is like fixing the memory of a horrible

blood-curdling dream," remembered a Southerner. But when the smoke

cleared, Leppien's battery belonged to the Confederates, Tower had

fallen with a serious wound, and a new Union brigade had appeared to

play its sacrificial role in the contest for Chinn Ridge.

|

POSTWAR VIEW OF THE CHINN HOUSE, SCENE OF HEAVY FIGHTING ON AUGUST 30.

(LC)

|

That brigade belonged to Robert Stiles and included among its four

regiments the Twelfth Massachusetts commanded by Fletcher Webster, son

of the celebrated statesman Daniel Webster. "Everything to our hasty

glance seemed confusion," confessed one of Stiles's men as the brigade

dashed into a rough line behind where Tower had once been positioned.

The two other brigades of Kemper's division, Eppa Hunton's and Micab

Jenkins's, did nothing to lessen the Federal consternation. They arrived

in the Chinn Branch swale and poured fire into the virtually defenseless

Federals. "We shot into this mass as fast as we could load until our

guns got so hot we had at times to wait for them to cool," reported a

South Carolinian. "This mass of Yankees was so near and so thick, every

shot took effect."

One of those shots found Fletcher Webster, who tumbled from his horse

with wounds in his arm and chest. Webster had written to his wife that

very morning explaining that "this may be my last letter, dear love; for

I shall not spare myself—God bless and protect you and the dear,

darling children." Webster would die within an hour of being hit.

Two more Union brigades arrived on Chinn Ridge, but they experienced

even less success than had McLean, Tower, and Stiles. The lead elements

of Jones's division George T. "Tige" Anderson's and Henry L. "Rock"

Benning's brigades, at last rendered Chinn Ridge untenable and by 6:00

P.M. Longstreet's troops stood alone in triumph atop the crest. But

their final goal still lay several hundred yards away. The ninety-minute

Federal defense of Chinn Ridge had measurably weakened the Confederate

juggernaut, causing such severe losses in Hood's and Kemper's divisions

that they could not participate in the push against Henry Hill. The

Fifth Texas alone lost 225 men killed and wounded at Manassas (including

a handful who had fallen on the twenty-ninth), more than any other

regiment in the army. Darkness would fall in about an hour, and although

Lee had clearly won the battle, during the next sixty minutes his best

chance to destroy Pope would hang in the balance.

Between 4:00 P.M. and 6:00 P.M. the Union commander did everything

possible to prevent such a catastrophe. With commendable energy and

reasonable efficiency Pope cobbled together a four-brigade defense line

along the western slope of Henry Hill, using Milroy's troops and men

from Reynolds's and Sykes's divisions. Two additional brigades provided

a reserve, so by the time Longstreet gained control of Chinn Ridge, Pope

had established a reinforced line of battle stretching nearly half a

mile from the ruins of the Henry house to the south end of the plateau.

Pope ordered Banks to sacrifice the army's supplies at Bristoe and move

to Centreville, where he could join Franklin, who had at last advanced

to the proximity of the battlefield.

|

AFTER NINETY MINUTES OF FIGHTING, THE STUBBORN UNION DEFENSE OF CHINN

RIDGE CRUMBLED IN THE FACE OF THE ADVANCING CONFEDERATE INFANTRY. (LC)

|