|

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

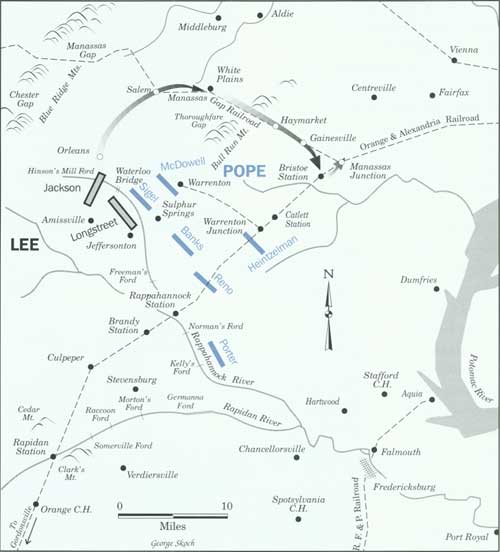

JACKSON'S FLANK MARCH, AUGUST 24-27, 1862

In the early

morning hours of August 2S, Jackson's men began crossing the

Rappahannock River at Hinson's Mill Ford. Forty-eight hours later after

covering fifty-six miles in the blistering August heat, Jackson lighted

in the rear of Pope's army at Manassas Junction.

|

On August 23 the Confederates faced the more immediate problem of

extricating Jackson's men from the north bank of the river near Sulphur

Springs. While Sigel slowly descended on the unsupported graycoats,

Jackson completed the construction of a new bridge late in the day and

removed his relieved troops before dawn on the twenty-fourth. But within

twenty-four hours Jackson would have them back across the Rappahannock

this time in much greater strength.

This movement would result from a council of war conducted on August

24 by General Lee at the village of Jeffersonton. The white-bearded

commander explained his intention to send Jackson's entire wing, some

24,000 men, on an ambitious march around Pope's right flank to alight

somewhere in the Union rear. Building upon the concept tested by Stuart

at Catlett Station, Jackson's force would fracture Pope's supply line

and thus persuade the Yankees to retire from their Rappahannock

defenses. From there the Army of Northern Virginia would respond to

whatever strategic opportunities the situation presented, including a

chance to strike Pope with advantage or a possible movement into

Maryland.

No matter what the potential rewards, Lee's scheme involved great

risk.

|

No matter what the potential rewards, Lee's scheme involved great

risk. Longstreet's divisions would occupy Pope's attention along the

Rappahannock during Jackson's flank march, but the wings of the

Confederate army would be dangerously divided. Should Pope discover

Jackson's detachment before Longstreet could close the gap, half of the

Confederate infantry faced mortal peril. Moreover, Lee knew that every

day might bring fresh units of McClellan's men to the equation.

Confederate strategy at Second Manassas thus rivaled the audacity of any

grand plan of the Civil War.

|

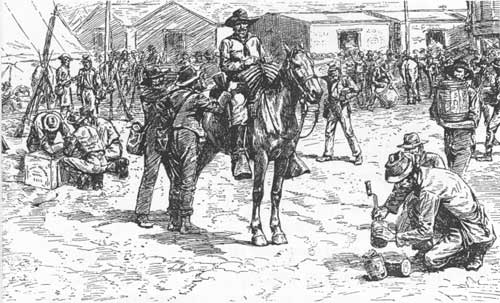

JACKSON'S "FOOT CAVALRY" ON THE MARCH. (BL)

|

Lee accepted the gamble because of his confidence in Stonewall

Jackson. "Old Blue Light" relished assignments such as this and used his

experience in the Shenandoah Valley as a model. Early on the morning of

August 25 Jackson assembled his three divisions, issued orders for an

expeditious, disciplined march, and began a journey that would take his

troops twenty-five miles before day's end.

Richard S. Ewell's brigades led the way. Ewell served under Jackson

in the Valley, and the two Virginians had established a relationship of

trust and mutual respect. Jackson's largest division, that of Ambrose

Powell Hill, followed Ewell. Hill possessed substantial military talent

leavened with a fiery temper and an oversensitivity to criticism and had

already run afoul of his infamously unforgiving commander. Jackson's old

division, now under William B. Taliaferro, brought up the rear. Jackson

thought little of Taliaferro and by year's end would rid himself of a

man he considered unreliable. The column waded a branch of the

Rappahannock tramped across fields, and negotiated streams heedless of

any specific highway. Their northward orientation led them to a point

near Salem (present-day Marshall), where the weary Confederates fell to

earth for a short night's rest.

|

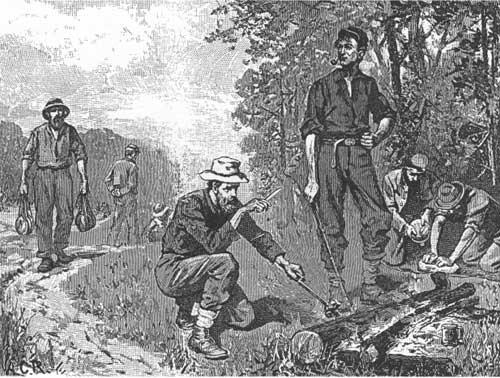

AFTER MARCHING IN THE STIFLING SUMMER HEAT, JACKSON'S EXHAUSTED SOLDIERS

DINED ON WHAT LITTLE THEY COULD FORAGE FROM THE SURROUNDING FIELDS.

(BL)

|

A movement of this magnitude could not go unnoticed. Indeed, early in

the morning alert Federal signal stations spotted Jackson's column, and

before noon Pope obtained an accurate idea about its size and direction.

What the Yankee observers could not decipher was Jackson's ultimate

destination, and here Pope stumbled. Instead of retiring from the

Rappahannock to block Jackson's approach, protect his supply base at

Manassas Junction, and prepare to unite with McClellan's units moving

south from Alexandria, Pope concluded that the Confederates were

shifting away from him toward the Shenandoah Valley.

Pope's error allowed Jackson on August 26 to turn east and pass

without interference through Thoroughfare Gap, a narrow defile in the

Bull Run Mountains. This craggy range of hills presented the only

natural obstacle between Jackson and the railroad. Likewise, safe

passage through Thoroughfare Gap provided the key to Longstreet's

eventual rendezvous with Stonewall somewhere on the plains of Manassas.

"Old Pete" had done his job well and left the Rappahannock late that

afternoon, but by then Jackson had covered more than fifty miles in the

thirty-four hours since his departure. "The march had been a rapid one

and the soldiers were weary, faint, and footsore," admitted one

participant, but all the labors of the past two days would mean nothing

unless Stonewall could take advantage of his perilous position in Pope's

rear earned by the exertion of his legendary "foot cavalry."

Pope's supply depot at Manassas Junction, the uninhabited

intersection of the Orange & Alexandria and Manassas Gap railroads,

offered the greatest reward to Jackson's exhausted brigades. But

Stonewall opted to steer his men first toward Bristoe Station, a whistle

stop several miles southwest of the junction. Seizing Bristoe and

wrecking the nearby bridge over Broad Run would cut Pope's direct rail

connection with his base and place a free-flowing obstacle between

Manassas and its dependent Union army. Moreover, Jackson learned that

only a handful of Federals guarded Bristoe, and he speculated that

Manassas might he better protected.

One after the other, the locomotives careened off the broken and

barricaded rails creating a spectacular scene of destruction. Had the

cars been loaded with soldiers, Jackson's men would have captured or

killed them all.

|

Early in the evening Stonewall's cavalry escort swooped upon the

startled Pennsylvanians carelessly encamped around Bristoe, dispersing

them with ease. Just then a whistle blast alerted the Confederates to

the approach of an empty Federal supply train returning to Manassas from

the front. Although the gray-clad raiders attempted to block the tracks,

the engineer barreled through occupied Bristoe, eventually spreading the

word that a Confederate force had once again gained Pope's rear. But his

warning did not reach the next two trainmen, who fell victim to

Jackson's vandals. One after the other, the locomotives careened off the

broken and barricaded rails creating a spectacular scene of destruction.

Had the cars been loaded with soldiers, Jackson's men would have

captured or killed them all.

The only Yankees in the neighborhood, however, were four miles up

the tracks at Manassas. The junction's small garrison responded to the

engineer's alarm by deploying infantry and artillery who prepared to

resist what they believed to be another cavalry raid similar to Stuart's

foray against Catlett.

Despite the late hour and the dusty miles already logged that day,

sixty-year-old Isaac R. Trimble volunteered two of his regiments for the

task of capturing Manassas. Supported by some of Stuart's cavalry,

Trimble pounced on the overmatched Unionists about midnight. "Our boys

gave them our best, but they were so close that our artillery only got

in about two or three shots apiece, when, in overwhelming numbers, they

were right among us in the darkness," reported the Federal commander.

Most of the Unionists surrendered. Jackson had thus brilliantly

accomplished the first portion of his assignment, but his ultimate

achievement would depend on the Federals' reaction.

|

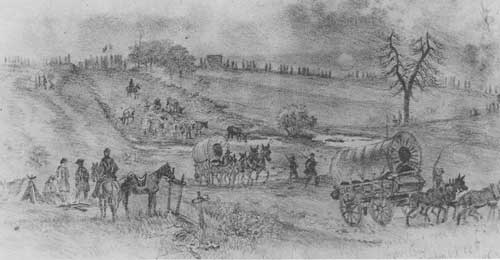

CONFEDERATE SUPPLY WAGONS NEGOTIATE A WATER CROSSING DURING THE FLANK

MARCH. (LC)

|

|

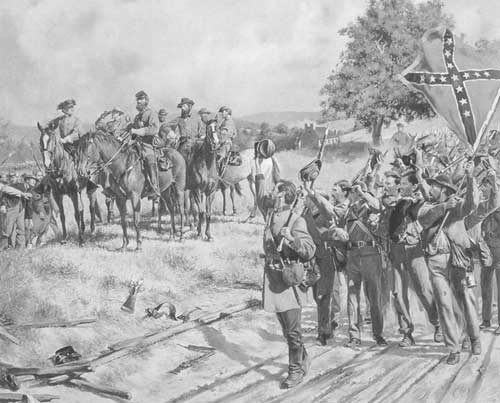

ORDERED TO MAINTAIN SILENCE, JACKSON'S MEN RAISE THEIR HATS IN MUTE

TRIBUTE TO THEIR BELOVED COMMANDER. (OLD JACK BY DON TROIANI, COURTESY

OF HISTORICAL ART PRINTS LTD., SOUTHBURY, CONNECTICUT)

|

To his credit, Pope saw opportunity where others might have panicked.

The Federal commander reasoned that an undetermined fraction of Lee's

army had advanced beyond its immediate supports, offering a rare

opportunity to crush his enemy in detail. Pope directed his 66,000 men

along the Rappahannock to abandon their positions on August 27 and fan

out along an eight-mile arc between the Warrenton-Alexandria Turnpike on

the left and the Orange & Alexandria Railroad on the right.

McDowell, in command of his own and Sigel's corps, would take the

turnpike, Reno and Philip Kearny's division of Heintzelman's corps would

occupy the center, while Heintzelman's other division under "Fighting

Joe" Hooker, followed by Porter's corps, would tramp beside the tracks

toward Bristoe and Manassas. Banks, still recovering from Cedar

Mountain, would guard the army's wagons in the rear.

Thirty miles east of Manassas Junction, General Halleck responded to

what on the night of August 26-27 he assumed to be only a cavalry

incursion. With the assistance of the energetic chief of military

railroads, Herman Haupt, Halleck assembled a reinforced brigade under

George W. Taylor to move toward Manassas, expel the pesky raiders, and

reestablish rail communication with Pope. Halleck also instructed

McClellan's newly arrived Sixth Corps under William B. Franklin to march

toward Gainesville on the Warrenton Turnpike and unite with Pope's

expanding army. Pope and Halleck, incommunicado because Jackson had

clipped the telegraph wires between Washington and the Rappahannock, had

thus unknowingly orchestrated a potent envelopment of Jackson's isolated

wing. Some 80,000 Federals were converging on Manassas from opposite

directions, and if all went well, Stonewall and his three divisions

might be eliminated.

As the sun rose on August 27, however, Jackson's first concern was to

reinforce Trimble at Manassas Junction. Stonewall left Ewell at Bristoe

to protect the Confederate rear and marched with Hill and Taliaferro to

the Union supply base. The sight that greeted the ragged Confederate

scarecrows boggled their minds. "At the Junction was a large depot of

stores [and] two trains containing probably two hundred large cars

loaded down with many millions of quartermaster and commissary stores,"

gushed one Rebel. "Beside these, there were very large sutlers' depots,

full of everything. In short, there was collected there, in the space of

a square mile, an amount and variety of property such as I had never

conceived of."

|

CONFEDERATE TROOPS PILLAGING MANASSAS JUNCTION LIKENED IT TO A

"WAREHOUSE FILLED WITH ALL THE DELICACIES." (BL)

|

|

JACKSON'S MEN BURNED WHAT THEY COULD NOT CARRY, LEAVING THE FEDERAL

SUPPLY DEPOT A SMOLDERING RUIN. (LC)

|

Before the awestruck Southerners had a fair chance to sample this

inspiring cornnucopia, Jackson's pickets announced the appearance of

enemy troops.

|

Before the awestruck Southerners had a fair chance to sample this

inspiring cornucopia, Jackson's pickets announced the appearance of

enemy troops. Hill's brigades first repulsed a heavy artillery regiment

en route to Manassas, but George Taylor's New Jerseyians offered a

larger target. The Garden Staters confidently approached to within a few

hundred yards of Jackson's concealed defenders before the landscape

exploded in a fury of lead and iron. The brave Yankees stood their

ground for ten minutes, ignoring Stonewall's personal appeals to

surrender. But numbers soon determined the outcome of this lopsided

contest, and Taylor retreated precipitately toward Bull Run, losing a

third of his men and suffering a mortal wound.

News of Taylor's disaster soon reached Washington, where George

McClellan had at last arrived to take command of the Peninsula veterans

intended to succor Pope. Instead of hastening Franklin's 10,000 fresh

rifles to the front as Halleck intended, McClellan canceled Franklin's

advance. "I have no means of knowing the enemy's force between Pope and

ourselves," McClellan told the general in chief. "I do not see that we

have force enough in hand to form a connection with Pope, whose exact

position we do not know." Herman Haupt tried frantically to persuade

McClellan of the need and practicality of releasing Franklin, but Little

Mac would hear none of it. McClellan had written his wife a few days

before that "I don't see how I can remain in the service if placed under

Pope," and now his excess caution would ensure that the despised

Illinoisan would control no more of the Army of the Potomac until

McClellan approved.

Meanwhile, Taylor's defeat allowed Jackson's victorious regiments to

indulge in what would possibly be the happiest day of their military

lives. "I saw the whole army become what appeared to me an ungovernable

mob, drunk, some few with liquor but the others with excitement,"

remembered a Louisiana chaplain. Actually the pious and prudent Jackson

had taken steps to discard the tempting intoxicants stashed among the

delicacies stockpiled at Manassas Junction. But the rest of the booty

presented fair game for the butternut desperados. The hungry men ate

their fill and then stuffed their pockets and haversacks with a variety

of edibles, drinkables, and tradables.

Ewell's brigades did not share in the initial revelry because they

found less pleasant employment in combat with the vanguard of Pope's

army at Bristoe Station. During the afternoon Hooker's division

approached the depot from the west and clashed with Ewell for an hour

before the Confederates executed a textbook withdrawal. The Rebels

crossed Broad Run, firing the bridge in their wake, while the bloodied

and exhausted Federals licked their wounds at Bristoe. Ewell's men did

reach Manassas at dusk and helped themselves to what remained of the

Union supplies, but one of Ewell's officers complained that other troops

had "appropriated the provisions of a more enticing character."

|

|