|

THE BATTLES FOR RICHMOND, 1862

It was mid-May 1862 when Jefferson Davis of Mississippi came to the

great crisis of his life. Davis had devoted his existence to serving his

home state and his country, and that path had led him to the presidency

of the Confederate States of America. Yet a lifetime of labor and

commitment to principle had brought him no repose to enjoy his

accomplishments. Indeed, in that spring of 1862, he found himself

standing not on a pinnacle of power but a precipice of defeat. His world

appeared to be on the verge of collapse, and he was virtually powerless

to stop it.

By mid-May 1862, newspaper editors across the divided nation openly

declared that Davis's battered Southern Confederacy was doomed.

Confederate troops had triumphed in the war's first major battle, at

Manassas, Virginia, in July 1861, but since then the litany of Southern

defeats was long and almost unbroken: in Tennessee at Forts Henry and

Donelson and at Shiloh, in Arkansas at Pea Ridge, in North Carolina at

Hatteras, Roanoke Island, and New Berne, in Georgia at Fort Pulaski, and

in Louisiana, where New Orleans, the South's largest and wealthiest

city, lived under Federal martial law. In Virginia, an army of more than

100,000 Federals, the largest army in American history to that point

stood just 25 miles from Richmond—the Confederacy's capital and its

leading industrial city. Richmond's defense depended upon an army of

60,000 inexperienced and poorly organized troops. Few disagreed when on

May 12, the New York Times declared: "In no representation of the

rebel cause is there a gleam of hope."

|

WITH 38,000 RESIDENTS IN 1860, RICHMOND RANKED THIRD IN POPULATION AMONG

ALL SOUTHERN CITIES. THE CITY'S CAPACITY FOR PRODUCING MANUFACTURED

GOODS, PARTICULARLY IRON, HELPED CONVINCE THE CONFEDERATE GOVERNMENT TO

RELOCATE THE CAPITAL HERE. OVERCROWDING AND SHORTAGES SOON BELIED THIS

IDYLLIC PICTURE OF CONFEDERATE RICHMOND. (LC)

|

It was in an atmosphere of desperation, therefore, that President

Davis convened his Confederate cabinet in mid-May. Davis asked these men

to consider the Confederacy's last ditch—what should they do if

Richmond were lost? Present at the meeting was Davis's military adviser,

General Robert E. Lee. Lee was a Virginian. His mother's father had been

one of the wealthiest landowners in the state. Lee's own father had led

troops under Washington in the Revolution and had served as governor of

Virginia. The fate of Richmond was therefore of more than professional

concern to the 55-year-old soldier. He courteously advised the

president that if Richmond fell, the next militarily defensible line in

Virginia would be along the Staunton River, about 100 miles southwest of

the city. Then, much to the surprise of the men present, Lee added a

personal opinion, almost a plea: "But," he said, in a firm voice,

"Richmond must not be given up"; tears welled in his eyes, "it shall not

be given up!"

Coming after months of Southern defeats, Robert E. Lee's emotional

declaration stands as a watershed in the early history of the

Confederacy. Jefferson Davis's dedication had been powerful and

unwavering in the first year of the war, but the South's oft-defeated

generals had been at best merely competent. Lee's ardor on behalf of

Richmond and all it symbolized suggested that perhaps he was a different

kind of soldier. Here was a military man who seemed touched by powerful,

even passionate determination. Within six weeks, the courtly Virginian

would reveal for all to see another side of his character—a

boldness and decisiveness that would very suddenly turn defeat into

victory and completely reverse the course of the war.

|

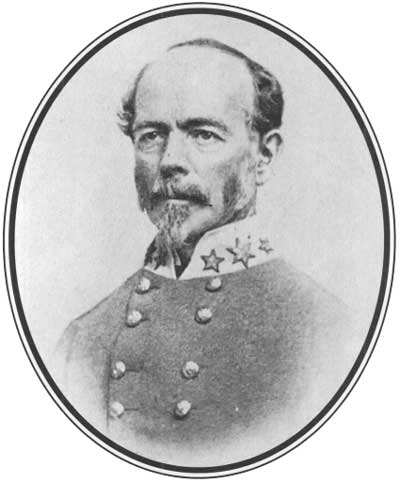

GENERAL JOSEPH E. JOHNSTON (USAMHI)

|

Before Davis appointed Lee to be his adviser in mid-March 1862, all

of the military problems of defending Confederate Virginia were laid at

the feet General Joseph F. Johnston. Small, trim, and meticulously neat,

the 55-year-old Virginian was a career soldier. Though popular with his

men, Johnston was proud to the point of perceiving slights where none

existed. After the Confederate victory at the Battle of Manassas on July

21, 1861, a victory that owed much to Johnston's leadership, the general

seemed jealous of credit going to anyone but him. Relations between

Johnston and his civilian superiors in Richmond were stormy, and the

general and President Davis seemed to be as much private adversaries as

public allies.

Perhaps worse than his strained relations with Davis was the

condition of Johnston's army. In April and May of 1861, a great many

Southerners had enlisted to fight for one year. Those enlistments would

expire in the spring of 1862 with the war far from won and as the

Confederacy was to face its greatest crisis. The Confederate Congress

passed a conscription act—the first in American history—which

drafted recruits and forced current soldiers to remain in

the ranks. The veterans were outraged, and morale and discipline

declined.

|

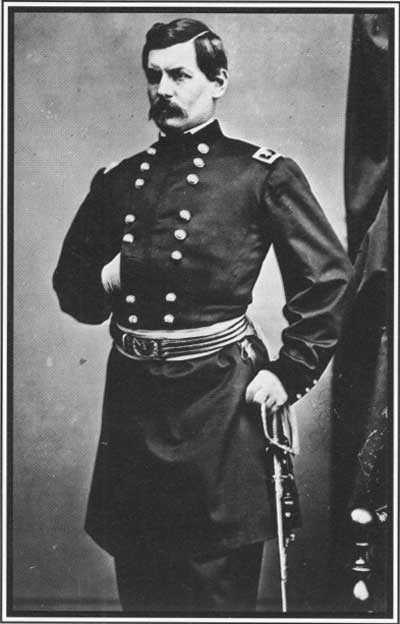

MAJOR GENERAL GEORGE B. MCCELLAN (LC)

|

Greatest of all of Johnston's concerns, however, was the position of

his army. His troops had spent the winter in camps around Manassas, a

railroad town about 30 miles west of Washington. By spring 1862,

Johnston could marshal only about 42,000 men and worried that the

Northerners would discover his weakness. In February, Johnston

conferred with Davis about pulling the army back from its advanced

position to a defensive line nearer the capital. The only results of the

seven-hour meeting were confusion and hard feelings. Davis later said

he had directed Johnston to stay at Manassas as long as possible.

Johnston believed he had discretionary power to withdraw whenever he

deemed it prudent. The misunderstanding led to a widening of the

breach between the general and the president, and as the battle for

Richmond loomed in the spring of 1862, the two men remained more than

ever disaffected partners in an unsteady alliance to save the

Confederacy.

But by the spring of 1862, the Federal army had grown so powerful

that the Confederates' plans seemed almost unimportant. The size of the

Federal Army of the Potomac—more than 200,000 men—led many in

Washington to think it virtually invincible. The great army's

commander, Major General George B. McClellan, "The Young Napoleon," as the

newspapers called him, was already the idol of his army and had many

admirers among the people of the North and the powerful of Washington.

If he took Richmond and ended the war, McClellan would be hailed as the

greatest hero of the age, and he knew it.

The mustachioed young general—he was only 35—was the

product of Philadelphia society. Graduated second in his class at West

Point, he had distinguished himself as a military engineer in the war

with Mexico and after. His superiors saw him as a rising star and

cultivated his professional growth, but despite his many

accomplishments, the young captain grew impatient with the slow

promotion and low pay in the army. He resigned in 1857 to begin a

promising and initially highly successful career as a railroad

executive. When the war came in 1861, George McClellan was considered

brilliant and popular and had been extraordinarily successful in the

army and in private business. It was logical that Northern leaders

looked to him to lead troops when the war broke out. Just three months

after the beginning of hostilities, President Abraham Lincoln called

McClellan to Washington to sort out the confusion in the wake of the

debacle at Manassas.

|

GEORGE B. MCCLELLAN (CENTER WITH SOME OF HIS SUBORDINATE OFFICERS).

(USAMHI)

|

|

MCCLELLAN'S HIS HEADQUARTERS NEAR YORKTOWN. (LC)

|

McClellan arrived in Washington in late July 1861 to find a

disorganized and defeated army of about 52,000 and a city full of

politicians near panic. Radiating competence and self-assurance, the

general soon calmed the hysteria. Within three months, he had 134,000

soldiers trained and armed around Washington, and the army was growing

by the week. The Northern states demonstrated their tremendous power and

commitment to the cause by sending tens of thousands of recruits and

hundreds of cannon to McClellan so that by the end of December 1861 the

Army of the Potomac numbered 220,000 men and more than 500 cannon—a

force many times greater than the largest army in the nation's

short history.

President Abraham Lincoln watched this impressive performance by the

young man and was inspired to give him even greater authority in

directing the Union war effort. On November 1, 1861, Lincoln appointed

McClellan to command "the whole army" of the United States. McClellan

would be responsible not just for the actions of his own army, but for

the movements of all the Federal armies in all the theaters of war.

Lincoln expressed concern that perhaps the job was too big for his young

general. McClellan's self-assurance seems to have had no bounds. He

told the president, "I can do it all."

But "Little Mac" had considerably less confidence in others.

Washington politicians in general and the president in particular appear

to have merited neither his admiration nor his trust. McClellan was a

conservative Democrat in a town where liberal Republicans held power.

Many Republicans wished to replace him at the head of the army with one

of their own. That Lincoln was not among these seems not to have

mattered to McClellan, for he clearly did not respect Lincoln as a man

or a leader. The general was negligent in paying to Lincoln the courtesy

traditionally due the president and on occasion referred privately to

the commander in chief as a "gorilla." Matters of decorum aside,

McClellan took pains to conceal from Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin

M. Stanton his plans for the spring campaigns. The general was

understandably concerned about security, but by showing such disrespect

for his civilian collaborators, who were also his legal superiors, he

almost certainly undermined their confidence in him.

As the winter weeks passed and the army grew, so did the outcry for

McClellan to do something. Unfazed, McClellan developed with great

deliberation his plan for a campaign he believed would end the war. His

national strategy called for a simultaneous movement by Federal armies

upon the heart of the Confederacy. According to his plan, Nashville

would fall, followed by all of Tennessee; Federal armies would secure

Missouri and the Mississippi River, New Orleans, the Carolina coasts

and, most important, Richmond. He thought the outcome by no means

certain if the job was undertaken hastily. "I have ever regarded our

true policy as being that of fully preparing ourselves, and then seeking

for the most decisive result," he wrote the president. In other words,

he wished no half measures; he wished to make one grand, overwhelming,

and irresistible effort.

|

THE LEGENDARY BUT INDECISIVE CLASH BETWEEN THE USS MONITOR AND

THE CSS VIRGINIA AT HAMPTON ROADS. (LC)

|

By December 1861, McClellan, had sketched out a plan for a campaign

in Virginia—a movement he would lead himself. His "Urbanna Plan"

called for the movement of the Army of the Potomac from Washington,

D.C., by water down the Chesapeake Bay to the river town of Urbanna,

Virginia, on the Rappahannock River, 60 miles from Richmond. From

Urbanna, the army would advance rapidly overland to Richmond. Despite

his reservations, Lincoln approved McClellan's plan of campaign as long

as the general would leave Washington secure in the army's absence.

But in early March, two events occurred that completely altered the

strategic picture in Virginia. A bright, clear Saturday, March 8, 1862,

became the most dismal day in the 86-year history of the United States

Navy. The Confederate ironclad Virginia, a vessel unlike any

warship ever seen afloat, steamed out of its homeberth at the Gosport

Navy Yard near Norfolk, Virginia, and attacked Federal ships in Hampton

Roads. Three hours later, two Federal frigates lay destroyed and 250

U.S. sailors and marines were dead or wounded. The Virginia,

scarcely hurt, would be ready to fight again the next day. Navy pride,

however, would be redeemed on that morrow by the just arrived little

gunboat USS Monitor. The historic clash between these two

ironclads on March 9 ended in a draw, and the Virginia retired to

her moorings in the Elizabeth River to refit and prepare for another

day.

It was the contemplation of another day like March 8 that dominated

the thinking of Federal strategists for more than two crucial months

that spring. Norfolk and its docks lay at the mouth of the James River.

About 100 tortuous miles upstream sat Richmond on high bluffs

overlooking the brown waters of the river that had helped make the city

the South's leading manufacturing center. If the combined forces of the

Federal army and navy sought a doorway to Richmond, the James was an

obvious and very desirable option—but not so long as the fearsome

Virginia guarded the entrance to Richmond's river. McClellan had

to look elsewhere for a route to the Confederate capital. Simply by its

existence, therefore, this single Confederate ship—the ugly,

turtlelike craft with balky engines—dominated the early phases of

the Federal conduct of the campaign.

The second pivotal event that March came when Johnston exercised what

he believed was his authority to withdraw from Manassas. His army moved

toward Gordonsville in central Virginia to a more secure position behind

the Rappahannock and Rapidan Rivers, leaving or destroying more than

750,000 tons of food, thousands of tons of clothing and supplies, and

dozens of heavy artillery guns at Centreville and Manassas. Davis was

angry, not just that Johnston had evacuated his position but that he

had been so hasty as to abandon food, supplies, and weapons precious to

the Confederacy.

The Confederates now sat on a railroad just several hours' ride from

Richmond. McClellan realized that his cherished scheme of an amphibious

sweep around the enemy's flank would no longer work as he had hoped.

"When Manassas had been abandoned by the enemy," he wrote after the war,

"and he had withdrawn behind the Rapidan, the Urbanna movement lost much

of its promise, as the enemy was now in position to reach Richmond

before we could do so." In the game of chess for control of Virginia,

Johnston had sidestepped the expected Federal offensive yet remained in

a fine position to react promptly to any Federal movement on Richmond.

Johnston waited for McClellan's next move.

McClellan, his generals, and the president finally agreed to proceed

with plans for the now less-lustrous amphibious route down the

Chesapeake Bay. The Federal commander planned to move to the Virginia

peninsula formed by the York River on the north and the James River on

the south. From Fort Monroe at the tip of the Peninsula, McClellan

intended, with the help of the U.S. Navy, to force the small Confederate

garrisons at Yorktown and Gloucester Point on the York River to retreat,

opening the York to Federal shipping. McClellan then hoped to move his

army by water up the river to West Point at the confluence of the

Pamunkey and Mattaponi Rivers. From West Point, McClellan hoped to move

quickly westward along the Richmond & York River Railroad to the

capital of the Confederacy just 30 miles away.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

THE PENINSULA CAMPAIGN BEGINS

General McClellan's original plan

called for a landing at Urbanna on the Rappahannock River. From there

the Army of the Potomac would march overland toward Richmond. The

Urbanna Plan was quickly discarded, however, when General Joseph

Johnston abandoned his position near Manassas Junction and ordered the

Confederate army closer to Richmond. The move forced McClellan to revise

his operation. He decided to land the Union army at Fort Monroe and

march up the peninsula between the York and James Rivers toward

Richmond.

|

McClellan was confident of victory, for his army seemed

irresistible. His host of 155,000 was the largest armed force in

American history to that point.

|

McClellan was confident of victory, for his army seemed irresistible.

His host of 155,000 was the largest armed force in American history to

that point—almost four times larger than the entire American army

in the Mexican War and seven times bigger than the largest force

McClellan had ever commanded in the field. "The Young Napoleon's" move to

capture Richmond was nothing less than the most enormous and complicated

military operation in U.S. history and would remain so even into the

twentieth century.

On March 17, the first of McClellan's troops departed aboard ship

from Alexandria, Virginia, and steamed down the Potomac. The Federals

had assembled a fleet of 389 steamers and schooners to transport the

army. For three weeks the waters of the Potomac churned with activity

as the invaders shipped vast numbers of men, animals, cannons, and

wagons southward. McClellan boarded a steamer at Alexandria on April 1

and cast off for his rendezvous with destiny. The general was deeply

happy to leave behind the politics of Washington and join the army in

the field. "Officially speaking," he wrote to his wife, "I feel very

glad to get away from that sink of iniquity."

But McClellan's troubles with Washington were just beginning. Lincoln

had stipulated that McClellan must leave about 40,000 men behind to

ensure that Washington was "entirely secure." McClellan reported he had

left more than 55,000 men behind, but the War Department learned that

only about 19,000 men remained to defend the capital and that 35,000 of

the troops McClellan counted as defenders of Washington were 100 miles

away in the Shenandoah Valley. The War Department immediately withheld

35,000 men slated to join McClellan, infuriating the general, who called

the order "the most infamous thing that history has recorded."

|

AFTER SUCCESSFULLY COMPLETING THE JOURNEY FROM ALEXANDRIA BY SHIP, UNION

SOLDIERS LANDED AT HAMPTON. (LC)

|

|

ALFRED R. WAUD'S DEPICTION OF MCCLELLAN RECONNOITERING THE LINES AT

YORKTOWN. (LC)

|

McClellan pushed onward from Fort Monroe toward the Confederate

fortifications at the historic old town of Yorktown. Admiral Louis M.

Goldsborough informed McClellan that the U.S. Navy could not assist him

in forcing past Yorktown, so the general planned to outmaneuver the

position and force the Confederate garrison to withdraw.

No sooner had McClellan's divisions moved forward than they

encountered the unexpected. The roads, which McClellan had told the

president were dry and sandy and passable in all seasons, were in

reality small and muddy. The continuous passage of heavy wagons,

artillery pieces, and thousands of men and horses churned the roads into

morasses of mud. The "rapid marches" that had composed a significant

component of McClellan's strategy, proved impossible, and every march

became a slow essay in exhaustion for the men of the ranks.

Even more fatal to McClellan's intentions was the discovery that his

maps were grossly inaccurate. The general was stunned to learn that the

Warwick River lay athwart his intended path and that the Confederates

had constructed elaborate fortifications on the west bank from Yorktown

to the James. McClellan's chief engineer declared that the line of works

was "certainly one of the most extensive known to modern times."

More distressing to McClellan were reports that the Confederates were

present in great strength across the Warwick. Federal officers reported

seeing long columns of Southern troops moving about and clearly hearing

the creaking and groaning of wagons and artillery on roads behind the

Confederate front lines. McClellan's intelligence operatives reported

that the Confederate garrison along the Warwick numbered perhaps

100,000, and the general decided that formidable works manned by so

many defenders were impregnable to assaults by infantry. An engineer by

training, McClellan had studied siege warfare and had brought with him

dozens of enormous artillery pieces—guns so large they could hurl

explosive shells weighing 200 pounds more than three miles. The Federal

commander knew that preparations for a siege would take many days,

perhaps weeks, but he reasoned that even though he would be losing time,

he would be saving lives.

The Warwick River defenses were not nearly as strong as he thought

they were. John B. Magruder commanded perhaps 13,000 Southern men in

Yorktown and along the Warwick, but he made the most of them. A career

soldier known among his brother officers of the old army for his panache

and theatrical flair, Magruder staged an elaborate show for McClellan's

scouts. Throughout April 4, Magruder ran his troops to and fro behind

the lines, across clearings and along roads, always with a view toward

being seen by the enemy. The newly arrived Federals counted many

thousands of gray-clad soldiers and reported to headquarters that the

Confederates seemed to be receiving heavy reinforcements. Magruder's

bluff helped convince McClellan that the Confederates were much too

strong to be dislodged quickly, and the Federals resigned themselves to

bringing up their heavy guns.

|

HIGH-TECH WARFARE, 1862

The high stakes of the Peninsula campaign—the fate of Richmond

and with it, perhaps, the Confederacy—drove leaders on both sides

to seek every advantage in battle, including using some of the latest

military technology on land, sea, and in the air.

Probably the most famous new weapon of the Peninsula campaign was the

ironclad warship. European naval engineers had experimented with

ironclad ships, but not until the spectacular events of March 1862 in

Hampton Roads, Virginia, did ironclads prove wooden warships were

obsolete. The turtlelike CSS Virginia and the new USS

Monitor, a "ridiculous-looking" vessel of radical design that one

soldier thought looked like a cheesebox on a giant pumpkin seed,

battled to an inconclusive draw on March 9, 1862, off the tip of the

Peninsula. Their duel marked a turning point in naval history and

revealed to the world that henceforth iron warships would rule the

waves.

Hot-air and gas balloons were not new in 1862, but technical problems

had limited the military uses of airships. An energetic 29-year-old New

Hampshire native named Thaddeus Lowe convinced both McClellan and

President Lincoln that balloons could be of great value in aerial

reconnaissance. Though Lowe had built and ascended in his first balloon just

four years earlier, Lincoln made him chief of army aeronautics in August

1861, and the young Yankee went to work creating a fleet of balloons,

the most famous of which was the Intrepid. He worked out a way to get

portable gas generators into the field and took them to the Peninsula,

where he immediately proved valuable. He and army officers made almost

daily ascents to gather intelligence on Confederate positions, and Lowe

became the first person to communicate with the ground from a balloon

via telegraph. Brigadier General Fitz John Porter went aloft to observe

Confederate activity at Yorktown when a tether line failed and winds

bore the balloon westward over enemy lines. Southern marksmen tried to

shoot the airship down, but the wind shifted and took Porter back to his

blue-suited friends.

Captain E. P. Alexander had charge of the Confederate aerial

reconnaissance program, which enjoyed few of the advantages of its

Northern counterpart. Lacking portable inflation machinery, the

Confederates had to fill the balloon at the Richmond Gas Works,

transport it by rail to the James River and tether it to a boat—the

CSS Teaser—a bargelike vessel that was arguably the first

aircraft carrier.

American businessmen had been using railroads for decades before the

Civil War, but not until the Peninsula campaign did military men see

what the iron roads could do for armies actively engaged in field

operations. McClellan made the Peninsula's one rail line—the small

Richmond & York River Railroad—a linchpin of his strategy. The

enormous Army of the Potomac consumed 600 tons of food, forage, and

supplies each day, every pound of which had to come hundreds of miles

from the North. Ships carried the food and supplies to the Peninsula,

and wagons took the materiel into the army's camps. Using the railroad

lifted a tremendous burden from McClellan's supply officers because it

could quickly move tons of rations to within a few miles of the army's

camps on the Chickahominy. So dependent did the Federals become on the

rails that one Union general stated that the Army of the Potomac could

not survive more than 10 miles from a railroad.

The Confederates used the railroads most profitably by moving men.

Five railroads converged at Richmond, and the Southerners brought troops

over the rails from North Carolina and other parts of the Confederacy to

defend the capital. Robert E. Lee's plan for a countermovement against

McClellan late in June probably would not have been possible had not he

been able to use the Virginia Central Railroad to move "Stonewall"

Jackson's men rapidly from the Shenandoah Valley to Richmond.

By far the most innovative use of railroads in the campaign sprang

from Lee's fertile mind early in June. Lee directed Confederate

military engineers to work with the C.S. Navy in mounting a powerful

Brooke Naval Rifle on a flatcar. This gun could accurately fire 32-pound

explosive shells more than a mile. The Confederates mounted the

7,200-pound cannon behind a sloping wall of iron affixed to the flatcar

and rolled the armored railroad gun—among the first in

history—into action at the Battle of Savage's Station, June 29,

1862. The gun accounted for some Federal casualties, but its chief

accomplishment seems to have been scaring Federal soldiers, many of them

patients in a nearby field hospital, with the screech of its large

shells.

More controversial were the shells deployed by Confederate Brigadier

General Gabriel J. Rains. Just before the Confederate evacuation of

Yorktown, Rains ordered his men to bury large artillery shells a few

inches underground around wells and in roadways and rig the devices to

explode when stepped on. Officers in both armies were still chivalric

enough to denounce the land mines as barbaric, and angry Federals used

Confederate prisoners to find and excavate the "infernal machines."

Of all the advanced implements of war used on the Peninsula, none

better represented the terrible destructive potential of modern

technology than Mr. Wilson Ager's volley gun.

|

Of all the advanced implements of war used on the Peninsula, none

better represented the terrible destructive potential of modern

technology than Wilson Ager's volley gun. Like the more famous Gatling gun,

this rapid-fire weapon was a direct ancestor of the modern machine gun

and spat scores of bullets per minute. Soldiers called it a "coffee mill

gun" because gunners loaded ammunition into a hopper and turned a hand

crank to fire the weapon. Several Ager guns saw action at Gaines's Mill,

where soldiers reported hearing "the quick popping of a rapid firing

gun" above the din of battle. The Agers had little effect at Gaines's

Mill but had far more significant influence in inspiring inventors to

create evermore devastating weapons and usher in the age of quick and

efficient wholesale destruction that is the hallmark of modern

technological warfare.

|

AERONAUT THADDEUS LOWE OBSERVING CONFEDERATE POSITIONS ON THE PENINSULA.

AT THE BATTLE OF GAINES'S MILL BOTH SIDES EMPLOYED GAS BALLOONS—THE

ONLY KNOWN CIVIL WAR BATTLE WHERE SUCH AN EVENT OCCURRED. (LC)

|

|

|

|