|

Johnston moved his army to the Peninsula to reinforce Magruder at

Yorktown, where Johnston assumed command. Though Magruder's extensive

preparations and imaginative theatrics had halted the Federal

advance—and the commanding general fully appreciated Magruder's

"resolute and judicious" efforts to buy the Confederacy precious

time—Johnston did not like what he saw along the Warwick. He was

not as impressed with the fortifications as was McClellan. "The works

had been constructed under the direction of engineers without experience

in war or engineering," he later wrote, and there was a dangerous

gap in the defenses near Yorktown. He felt certain a determined assault

would pierce the Warwick line.

Perhaps the more compelling reason behind Johnston's disdain for the

Confederate works on the lower Peninsula was that they did not fit in

with his plans, and he did not wish to hold them. Johnston believed that

however strong were the entrenchments themselves along the Warwick,

"they would not enable us to defeat McClellan." He was convinced that

"we could do no more on the Peninsula than delay General McClellan's

progress toward Richmond." A Federal breakthrough along the Warwick was

inevitable, he thought, and because the flanks of Magruder's line were

vulnerable the position was doomed. If the Federal navy wrested control

of either the York or the James and passed gunboats upstream beyond the

Confederate flank, Johnston's position would be untenable. The general

wished to withdraw from Yorktown immediately to take up a defensive

position closer to the capital. President Davis and Robert P. Lee also

understood that the rivers were the key to the defenses of Yorktown but

saw that Johnston could buy valuable time for the Confederacy by keeping

McClellan at bay on the Warwick. The longer the Federals sat stymied,

the more time Davis and Lee would have to gather troops from across the

Confederacy and move them to Richmond to confront McClellan. Johnston,

Davis, and Lee met on April 14 in Richmond but could come to no

agreement. Lee argued vehemently with his old friend (Lee and Johnston

had been classmates at West Point) that time was of the essence.

Johnston thought holding the Warwick was a flirtation with disaster and

left the meeting determined to evacuate Yorktown as soon as possible,

but he did not declare as much to Davis and Lee, who assumed the army

commander would hold his position until they could all discuss it

again.

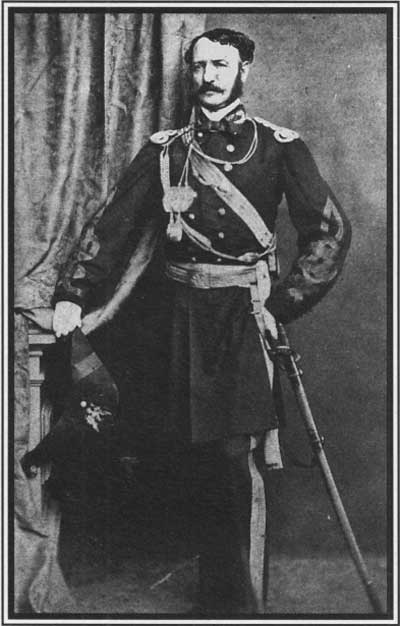

|

JOHN B. MAGRUDER (LOUISIANA STATE UNIV.)

|

On the morning of April 30, McClellan wrote to his wife that

preparations were almost complete for opening fire with the siege guns.

"We are working like horses and will soon be ready to open. It will be a

tremendous affair when we do begin, and will, I hope, make short work of

it."

But the Confederates too had been working. For Johnston, the issue at

Yorktown was whether he could get his army away before the Federals were

ready to begin their bombardment. By May 3, Johnston and his army were

about ready, and the general planned to screen his withdrawal with a

bombardment from his own heavy guns. Later that day, Johnston's

batteries opened on the Federal lines. "The shells from the rifled guns

flew in all directions," noted one of McClellan's staff officers. The

firing continued into the night, and the roar was deafening.

|

A SECTION OF THE CONFEDERATE LINES AT GLOUCESTER POINT, TYPICAL OF THE

FORMIDABLE DEFENSES THAT STALLED MCCLELLAN'S ADVANCE. THIS PHOTOGRAPH

WAS TAKEN AFTER JOHNSTON EVACUATED. (LC)

|

|

ALTHOUGH NEVER FIRED AGAINST THE CONFEDERATES, THESE SIEGE MORTARS WERE

PART OF A MASSIVE CONCENTRATION OF UNION ORDNANCE THAT HELPED PERSUADE

JOHNSTON TO RETREAT. (LC)

|

Dawn at last came, "silent as death," according to one Federal. Far

forward, along the picket lines, the Federals crept forward and

discovered the startling news: the Confederates were gone.

As soon as he learned of Johnston's pullout, a jubilant McClellan

ordered his divisions forward in pursuit. Soupy roads slowed both

armies, and rain continued to fall. Johnston kept with the head of his

column as it labored through the mud, so not until the afternoon of May

5 did he learn that the Federals had attacked his rear guard at

Williamsburg, eight miles from Yorktown.

Long before the Federals had arrived on the Peninsula, Magruder's

Confederates had built a line of earthworks just east of the old

colonial capital of Williamsburg. The defensive line's centerpiece, Fort

Magruder, dominated the main road from Yorktown. In the cold, rainy dawn

of May 5, Southern infantrymen and artillerymen lay in the muddy

earthen ramparts of the fort and peered eastward into the murk. Federals

of Brigadier General Joseph Hooker's division strode through the fog

toward Fort Magruder and immediately deployed for an attack. Confederate

artillerymen in the fort opened an accurate fire, and Confederate

infantrymen soon joined the fight. Major General James Longstreet, a

South Carolinian and perhaps Johnston's most trusted lieutenant,

conducted the engagement in Johnston's absence and sent more Southern

brigades that came forward to counter the persistent Hooker. The fighting

shifted southwestward from Fort Magruder, where Brigadier General

Richard H. Anderson advanced through tangled woods to assail Hooker's

left. Longstreet eventually committed his entire division of six

brigades against Hooker's three, and the Federals barely held their

own.

Brigadier General Philip Kearny's division came to Hooker's relief.

Certainly one of the more colorful figures in either army, Kearny led

his men up from the rear, flourishing his sword in his one hand —he

had lost his left arm in the Mexican War. Kearny cantered forward on a

personal reconnaissance to draw enemy fire. Two riders with him fell

dead, but the general returned to his troops pleased, for the

Confederates in the woods had revealed their positions. "You see, my

boys, where to fire!" he shouted, and his worshipful men sprang forward

with a yell. Kearny urged regiment upon regiment forward, shouting,

"Men, I want you to drive those blackguards to hell at once." Anderson's

Confederates fell back, and the fighting southwest of Fort Magruder

settled into a stalemate.

|

AFTER YORKTOWN, MCCLELLAN'S SOLDIERS STRUGGLED TO CATCH JOHNSTON'S

RETREATING ARMY, BUT RAIN-SWOLLEN CREEKS AND MUDDY ROADS IMPEDED THEIR

ADVANCE. (LOSSING'S CIVIL WAR IN AMERICA)

|

North of the fort, however, a Federal brigade moved forward into what

appeared to be a gap in the Confederate line. Brigadier General Winfield

S. Hancock, a Pennsylvanian, pushed his men onward until he found

himself in the Confederate rear and approaching Fort Magruder from

behind. Longstreet, with all of his troops engaged with Hooker and

Kearny, had no reserve with which to counter Hancock and sent an urgent

appeal to Major General D. H. Hill for reinforcements. Hill sent

Brigadier General Jubal A. Early and his four regiments hustling to the

Confederate left. Early's Virginians and North Carolinians emerged from

a forest and found themselves in the open directly before Hancock's

troops. Early launched an attack, and a Federal officer on the battle

line recalled that Hancock's line moved swiftly to counter it: "We

halted and opened fire, and the view of it through the smoke was

pitiful. They were falling everywhere; white handerchiefs were held up

in token of surrender. . . . We gathered in some three hundred prisoners

before dark." All told, Early had lost more than 500 men (300 from the

5th North Carolina alone) and had himself been gravely wounded.

|

THIS FANCIFUL KURZ & ALLISON PRINT OF THE BATTLE OF WILLIAMSBURG

REFLECTS THE ROMANTIC MOOD OF THE POST WAR YEARS, NOT THE BRUTAL

REALITIES OF CIVIL WAR COMBAT. (LC)

|

|

MCCLELAN'S SUPERIOR LOGISTICAL ABILITY MANIFESTED ITSELF ON THE WHARVES

OF YORKTOWN WHERE HE STOCKPILED STORES OF AMMUNITION AND EQUIPMENT.

(USAMHI)

|

The battle sputtered to a close in the soggy darkness, and commanders

were left to count their dead, wounded, and missing. In this first

pitched battle of the Peninsula campaign, the Federals spent 2,200 men

in trying to smash the Confederates from behind, and the Southerners

lost 1,600 soldiers in fending off the Federal attackers.

But McClellan had already undertaken a more ambitious movement aimed

not at the tail of the retreating Confederate column but at its head. As

his divisions had streamed through Yorktown and on to Williamsburg on

May 4 and 5, McClellan went to the wharves of Yorktown to oversee the

loading of 11,000 soldiers and their supplies and equipment on to

steamers and barges. The general's plan was for his close friend

Brigadier General William B. Franklin to lead a division up the York

River, which, with the abandonment of the Confederate batteries at

Yorktown and Gloucester Point, was open to Federal shipping. Franklin

was to establish a landing near West Point and, if possible, strike

inland at Johnston's retreating column. If all went well for the

Federals, Franklin's move might be the bold stroke of the campaign—the

blow that might severely hurt Johnston and, perhaps, set

enough dominoes tumbling to lead to the fall of Richmond. But neither

McClellan nor Franklin seemed to have the heart to deliver a crushing

blow. McClellan seemed more concerned about the risks involved than the

victory to be won and emphasized caution. Rather than releasing this

flanking force for a daring thrust, McClellan seemed satisfied to place

Franklin on Johnston's flank and keep him there on a leash.

Franklin landed at Eltham's Landing on the Pamunkey River on the

afternoon of May 6 while most of Johnston's army was still slogging

along the muddy roads from Williamsburg. Instead of striking inland to

intercept the enemy, Franklin adhered to the spirit of his orders and

fortified the landing site. Three Confederate brigades stifled a small

Federal sally the next day, ending McClellan's best opportunity yet to

hit the Confederates hard away from the protection of their

earthworks.

Franklin did, however, establish a beachhead, and McClellan's supply

officers immediately sent heavily laden vessels up the York. For the

next seven weeks, the York would be one of the busier rivers in America

as craft of all types labored to supply the army as it moved toward

Richmond.

The James River, to the south, would be less busy but no more placid.

In the second week of May, the U.S. Navy at last got its chance to add

its heavy ordnance to the contest on the Peninsula. When Johnston had

evacuated Yorktown, the commander of the Confederate garrison at Norfolk

withdrew his troops toward Richmond, abandoning the Gosport Navy Yard,

home port of the ironclad Virginia. The James River was too

shallow for the ironclad to retreat toward Richmond so, reluctantly, the

captain scuttled and burned his ship before dawn on May 11. It was an

ignominious end for the ship that had dominated the campaign for two

months.

|

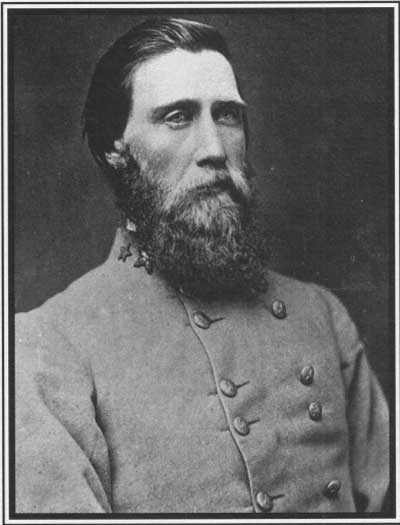

JOHN B. HOOD COMMANDED THE CONFEDERATES ENGAGED AT ELTHAM'S LANDING ON

MAY 7. (LC)

|

Free at last from the shadow of its nemesis, the U.S. Navy

immediately entered the waters of the James that the Virginia had

so long denied them. Admiral Louis M. Goldsborough placed five gunboats

under the command of Commander John Rodgers and ordered the squadron to

push upriver to Richmond. Goldsborough told Rodgers to "shell the place

into a surrender."

Davis and others in Richmond clearly understood the gravity of the

situation. The president told Virginia's legislature that he intended to

hold Richmond, but the statement was neither a promise nor very

convincing. "There is no doubt," wrote Richmond newspaperman Edward

Pollard, "that about this time the authorities of the Confederate

States had nigh despaired of the safety of Richmond." While their

leaders spoke of brave deeds and the need for courage, the people of

Richmond watched as the Confederate government began packing up. "They

added to the public alarm by preparations to remove the archives,"

Pollard wrote. "They ran off their wives and children to the country."

Davis himself had sent his wife and children to safety in North

Carolina. "As the clouds grow darker and when one after another of those

who were trusted are detected in secret hostility," he wrote, she must

try to "be of good cheer and continue to hope that God will in due time

deliver us from the hands of our enemies and 'sanctify to us our deepest

distress.'"

|

WITH THE GALENA IN THE ADVANCE AND THE FAMOUS MONITOR

NEARBY, RODGERS'S SQUADRON BOMBARDED DREWRY'S BLUFF FOR MORE THAN THREE

HOURS BUT WAS UNABLE TO SILENCE THE CONFEDERATE BATTERIES. (FRIENDS OF

THE NAVY MEMORIAL MUSEUM)

|

|

A PHOTOGRAPH OF THE BATTERED IRONCLAD GUNBOAT GALENA TAKEN

SHORTLY AFTER ITS FAILED ATTACK AGAINST DREWRY'S BLUFF. (LC)

|

Just eight miles south of Richmond, hundreds of Southern soldiers,

sailors, marines, militiamen, and civilians labored to obstruct the

James River and thus seal off the greatest immediate threat to the

capital. For weeks, men had worked to finish a fort high atop the

90-foot-high Drewry's Bluff. Work on the defenses continued through the

night of May 14, when the Southerners sank cribs full of stones and

small ships to close off the river's channel.

Rodgers's squadron steamed around a sharp bend at 7:30 A.M. on May 15

and came under fire from the guns on the bluff (the Federals referred to

the earthworks on the heights as Fort Darling). Rodgers boldly steered

his flagship, the ironclad USS Galena, to within 600 yards of the

fort. The other gunboats, the Monitor, Aroostook, Port Royal, and

Naugatuck, anchored behind the Galena and returned fire.

The Southern artillerymen concentrated their fire on the Galena,

and the riflemen along the river's edge sniped at the Federal gun crews.

More than three hours after the fight had begun, Rodgers decided he

could do no more. "It became evident after a time that it was useless

for us to contend against the terrific strength & accuracy of their

fire," wrote an officer on the Monitor. The Galena, having

expended 360 rounds, was nearly out of ammunition and was on fire.

Rodgers ordered his ships to retire downriver.

The Galena had been hit 45 times. One onlooker thought her

iron sides had offered "no more resistance than an eggshell." An officer

of the Monitor was stunned by what he saw belowdecks on the

Galena, where 13 men had been killed and 11 others

wounded—"she looked like a slaughterhouse. . . . Here was a body

with the head, one arm & part of the breast torn off by a bursting

shell—another with the top of his head taken off the brains still

steaming on the deck, partly across him lay one with both legs taken off

at the hips & at a little distance was another completely disemboweled.

The sides & ceiling overhead, the ropes & guns were

spattered with blood & brains & lumps of flesh while the decks

were covered with large pools of half coagulated blood & strewn with

portions of skulls, fragments of shells, arms legs, hands, pieces of

flesh & iron, splinters of wood & broken weapons mixed in one

confused, horrible mass."

Richmond celebrated the repulse of Rodgers as the first good news in

weeks. The James River route to the city had again been denied to the

Federal navy at the cost of just seven Confederates killed and eight

wounded.

|

THIS PANORAMIC VIEW SHOWS CUMBERLAND LANDING ON THE PAMUNKEY RIVER, USED

BY MCCLELLAN BEFORE HE MOVED THE ARMY'S SUPPLY BASE TO WHITE HOUSE

LANDING. (USAMHI)

|

|

THE "WHITE HOUSE" AT WHITE HOUSE LANDING WAS HOME TO CONFEDERATE OFFICER

W. H. F. "ROONEY" LEE, SON OF GENERAL ROBERT E. LEE. THE HOUSE WAS

UNFORTUNATELY BURNED TO THE GROUND DURING THE FEDERAL EVACUATION IN

JUNE. (BL)

|

With proper management and good fortune, any of the three Federal

thrusts in the first half of May—those at Williamsburg, Eltham's

Landing, and Drewry's Bluff—might have proved fatal to Johnston's

defense of Richmond. But the Federals had been neither adroit nor lucky,

and the Confederates drew confidence from the Federal failures as the

initiative in the campaign shifted slightly toward Johnston. McClellan

seemed willing to let it pass, for after the setback at Eltham's

Landing, he had ceased pursuing Johnston with vigor and moved haltingly

toward the Pamunkey River, where his quartermasters were accumulating

vast supplies.

On May 16, McClellan established his base of supply at White House

Landing, where the Richmond & York River Railroad crossed the

Pamunkey. Just a few miles west of White House lay Johnston's army,

where it had been resting undisturbed for more than a week. McClellan

expected a climactic battle within days near the Chickahominy River, but

he admitted he could not discern what Johnston was up to. "I don't yet

know what to make of the rebels," he confided to his wife. "I do not see

how they can possibly abandon Virginia and Richmond without a

battle."

Johnston did not intend to give up Richmond without a battle, but he

wished only to fight where and when it would favor his outnumbered army.

The Confederates stood with their backs to the Chickahominy River, a

shallow but broad, swampy morass prone to severe flooding. Johnston

decided he wished this obstacle between him and the enemy rather than

between his army and Richmond. On May 16, Johnston crossed the army to

the south bank of the Chickahominy and took up positions west of the

crossroads of Seven Pines.

|

THE PRESENCE OF UNION SOLDIERS ON THE PENINSULA REPRESENTED THE

POSSIBILITY OF FREEDOM FOR THOUSANDS OP SLAVES, MANY OF WHOM RAN AWAY

FROM THEIR MASTERS AND SERVED AS LABORERS IN THE UNION ARMY, INCLUDING

THIS GROUP OF MEN AT WHITE HOUSE LANDING. (USAMHI)

|

Despite having made his third retrograde movement in the first three

weeks of the month, Johnston was thinking offensively. He knew he would

have to fight McClellan soon, but he wished to do so under the most

advantageous circumstances possible. The Confederate commander

believed that if he soundly defeated McClellan far from his safe haven

at Fort Monroe, the Southerners could vigorously pursue the broken

Federals and destroy the Army of the Potomac. "If the Federal army

should be defeated a hundred miles away from its place of refuge, Fort

Monroe," he wrote, "it could not escape destruction. This was

undoubtedly our best hope." Contemplating this scenario, Johnston

waited west of Seven Pines and watched for an opportunity to strike.

McClellan now had a serious strategic problem before him, and he

knew that how he resolved that problem would affect every decision he

would make for the rest of the campaign. The Federal commander was

having trouble feeding his enormous army. He discovered that his 3,000

wagons, working in tandem with the railroad, were just barely adequate

to satisfy the daily requirements of his 115,000 men and 25,000 horses

and mules. The thought that he might not be able to supply his army by

wagon alone, particularly in rainy weather over muddy roads,

understandably made McClellan reluctant to leave the railroad.

Logistically, the railroad offered McClellan a great advantage in

moving supplies to his troops, but to capitalize on this advantage, he

had to hold both banks of the Chickahominy. Strategically, it would have

been better to have consolidated the army all on one side of the river

so neither wing would be isolated from the other. The principles of

strategy and logistics were thus working against each other in

McClellan's approach to Richmond. Opting to resolve supply problems

first, even at the expense of creating strategic problems, McClellan

followed Johnston across the Chickahominy with part of his force.

On May 17, after McClellan had established his base at White House,

he received welcome news from the War Department. Irvin McDowell's

30,000 troops, then at Falmouth on the Rappahannock River, would march

overland and join McClellan in his operations on Richmond. McClellan

was pleased indeed to have these long-awaited reinforcements, but he

was correspondingly outraged when a week later the War Department

suspended the order and sent McDowell instead to the Shenandoah Valley.

Confederate Major General Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's fast-marching

troops had defeated one Federal force in the Valley, attacked another,

and seemed capable of crossing the Potomac River and threatening

Washington. Jackson's hyperactive campaign in the Valley—in which

his men would march more than 600 miles and fight five

engagements—was part of a scheme developed by Jackson and Robert E.

Lee to divide Federal attention. Jackson's force was relatively

small—never more than 17,000 men—but the two generals hoped

that by swift forced marches and surprise attacks Jackson's little army

could raise havoc with the Federals in the Valley and thereby create in

the minds of strategists in Washington the impression of a serious

crisis. Lee hoped Washington would try to subdue Jackson by diverting

troops from McClellan, thereby decreasing Federal pressure on Richmond.

The Federal War Department unknowingly complied with Lee's wishes and

ordered McDowell westward to help corral Jackson. McClellan saw the

Lee-Jackson scheme for what it was—a diversion—and he

complained bitterly to Washington about sending troops to the Valley on

a wild goose chase, but to no avail; he would have to do without

McDowell for a while longer.

|

MAJOR GENERAL THOMAS J. "STONEWALL" JACKSON. (LC)

|

On his own, with no prospect of reinforcement any time soon,

McClellan tried to sort out the strategic situation before him in the

final week of May.

|

On his own, with no prospect of reinforcement any time soon,

McClellan tried to sort out the strategic situation before him in the

final week of May. Johnston lay behind fortifications west of Seven

Pines. To get at him, McClellan would have to cross the Chickahominy in

sufficient force to defeat Johnston yet leave a strong force north of

the Chickahominy to protect the railroad. In looking for his next move,

McClellan's gaze turned to a gathering Confederate force north of the

river near the village of Hanover Court House. McClellan saw that

advancing on Johnston south of the river would place these Confederates

on his flank, where it might prove troublesome, so the Federal commander

decided to eliminate it before he turned his full attention to

Johnston.

In the predawn hours of May 27, a Federal column commanded by

Brigadier General Fitz John Porter moved northwestward through a rain

storm toward Hanover Court House. Porter surprised a Confederate brigade

commanded by former U.S. congressman Lawrence O'B. Branch, but the

Southerners, mostly North Carolinians, fought bravely against more than

twice their number. The ugly little fight sprawled through the woods and

farm fields south of Hanover Court House for several hours before Branch

withdrew his battered regiments toward Richmond. The Southerners had

lost more than 750 men and the Federals 355, but McClellan had

accomplished his objective and could now attend to Johnston.

But Johnston had already been studying McClellan's positions, and he

saw that for all the Northerner's deliberations and meticulous planning,

McClellan had made a careless error. While retaining most of his army

north of the Chickahominy, the Federal commander had sent just two

corps—the Fourth and the Third—across to the south bank. The

Third Corps, under Brigadier General Samuel P. Heintzelman, remained in

a reserve position close to the river while Brigadier General Erasmus D.

Keyes's Fourth Corps advanced to the Seven Pines intersection, nine

miles from Richmond. This single corps of 17,000 men confronted the

majority of the 63,000 men Johnston had at his disposal. Neither Keyes

nor McClellan seem to have realized the extreme danger of the Fourth

Corps's position, separated as it was from most of the army with only

one bridge linking the wings across the Chickahominy. Even worse was

that Keyes had pushed his weakest division, Brigadier General Silas

Casey's 6,000 men, the smallest and least experienced division in the

army, farthest forward to hold the most advanced position in McClellan's

army—a line of earthworks just west of Seven Pines. In advancing on

Johnston, McClellan had arguably put his worst foot forward.

|

THREE DAYS BEFORE THE BATTLE OF HANOVER COURT HOUSE, THE LEADING

ELEMENTS OF MCCLELLAN'S ARMY ENTERED MECHANICSVILLE. (BL)

|

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL SILAS CASEY (BL)

|

Johnston had been looking for an opportunity to attack McClellan on

favorable terms, and his numerical superiority south of the

Chickahominy gave him the advantage he sought. Johnston decided to

attack the Fourth Corps at Seven Pines and met with General Longstreet

on the afternoon of May 30 to complete a plan. Johnston's design was not

complicated. Two strong columns, one of six brigades under Longstreet

and the other of four brigades under D. H. Hill, would converge via

separate roads on the Fourth Corps at Seven Pines. A third column of

three brigades under Major General Benjamin Huger was to support Hill's

right (the far Confederate right). G. W. Smith's division, temporarily

under Brigadier General W. H. C. Whiting, was to follow Longstreet's

column to add support as needed. If all went well, the Fourth Corps

would be crushed and the Third Corps would be pinned against the

Chickahominy and overwhelmed.

But three factors conspired to complicate the attack. The first was

James Longstreet, who, without informing Johnston, decided to

drastically alter the plan. For reasons he never satisfactorily

explained, Longstreet chose to forsake his assigned attack route on the

Nine Mile Road and move his column to join Hill on the Williamsburg

Road. By this movement, the two converging columns became one very large

force packed into a very narrow space so that it could only attack

frontally and with a fraction of its force at a time.

|

MAJOR GENERAL DANIEL H. HILL (LC)

|

|

BATTERY A, 2ND U.S. ARTILLERY AFTER THE BATTLE OF SEVEN PINES. (LC)

|

The second factor complicating Johnston's attack was the weather. On

the night of May 30, a raging storm lashed the Chickahominy basin.

"Torrents of rain drenched the earth," recalled an awed General Keyes,

"the thunder bolts rolled and fell without intermission, and the heavens

flashed with a perpetual blaze of lightning." The deluge turned the

river into a furious flood and swelled small tributaries beyond

fordability. Slippery mud made the Confederates' task of moving large

numbers of men over small roads even more difficult than it already

was.

Finally, the imprecision of Johnston's instructions to his generals

would contribute to the confusion. Huger suffered most from Johnston's

muddled orders, and the mud and high water in creeks and streams coupled

with Longstreet's crowding onto the Williamsburg Road delayed Huger's

march by several hours. The scheduled dawn attack did not begin until 1

P.M., when an impatient D. H. Hill sent his brigades forward

unsupported.

Immediately in the path of Hill's men, hunkered down in flooded rifle

pits, lay the novices of Silas Casey's division. Casey himself admitted

that his men were ill trained and poorly equipped, and though the

general was working diligently at making his men better soldiers, he

knew they probably were not ready for a fight. D. H. Hill's men were

about to accelerate the learning process for Casey's green Yankees. The

Federal line shuddered under Hill's initial blow, some units broke and

ran, but as the crucial minutes passed it became clear that Casey's

untested rookies would hold their ground and fight. Still, the

attacking Confederate force was too large for Casey to handle alone, so

as his men withdrew deliberately he called for reinforcements. Casey's

corps commander, Keyes, was slow in sending supports to threatened

points, and Hill's men continued advancing.

|

UNION SOLDIERS PERFORMING THE GRUESOME TASK OF BURNING SLAIN HORSES AND

BURYING THE DEAD AFTER SEVEN PINES, NOT FAR FROM THE FAMOUS TWIN HOUSES

AND CASEY'S REDOUBT. (BL)

|

The recent downpours had turned part of the battlefield into a swamp

and flooded rifle pits and entrenchments. Confederate regiments went

forward through hip-deep water, and officers had to form details to

follow along behind the battle line and prop up the wounded against

trees to prevent their drowning. The volume of fire was terrific, and

men on both sides fell in incredible numbers. An Alabama colonel was so

engrossed by the effort to save his regiment that he considered it his

duty to ignore a personal tragedy. Colonel John B. Gordon passed his

brother, a 19-year-old captain. "He had been shot through the lungs and

was bleeding profusely," recalled Gordon. "I did not stop; I could not

stop, nor would he permit me to stop. There was no time for that—no

time for anything except to move on and fire on."

About 4:40 P.M., D. H. Hill, strengthened by reinforcements from

Longstreet, surged forward to hit a new Federal line near Seven Pines,

this one anchored by troops under Brigadier General Samuel P.

Heintzelman, commander of the Third Corps. Heintzelman's line held, even

after a lone Confederate brigade commanded by Colonel Micah Jenkins

stove in Heintzelman's right flank. Unsupported, Jenkins had to retire

when the Federals brought up reserves.

Johnston remained near his headquarters through the early part of

the day. He had not heard from Longstreet and did not know about the

altered plan, but by mid-morning, he knew something had gone seriously

wrong. About 4 P.M., Johnston received a note from Longstreet asking his

commander to join the battle. Puzzled and still in the dark, Johnston

went forward with three brigades of Smith's Division (under W. H. C.

Whiting). Near Fair Oaks Station on the railroad, Johnston's column

encountered resistance. These Federals finally halted the Confederate

column but only when reinforcements arrived after one of the more

remarkable forced marches of the war.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

BATTLE OF SEVEN PINES—MAY 31

After a morning of confused

and misunderstood orders, the Confederates finally struck McClellan's

advance at Seven Pines. Silas Casey's untried division fell back to

Seven Pines intersection, where reinforcements halted the Southern

advance. Army commander Joseph E. Johnston fell wounded while watching

his troops in action near Fair Oaks Station.

|

When Brigadier General Edwin V. Sumner, commander of the Second Corps

on the north side of the Chickahominy, heard the sounds of battle at

Seven Pines, he, on his own initiative, sent troops forward as

reinforcements. His men had to cross the swift and turbulent waters of

the rain-swollen river, but the only crossing available was Grapevine

Bridge, which was partially submerged and threatening to wash away at

any moment. Sumner ordered his men on to the groaning, swaying span. The

weight of the passing column helped the bridge hold against the rushing

waters, but soon after the last man reached the south bank, the timbers

collapsed and were borne away by the roiling stream. Sumner's men, led

by Brigadier General John Sedgwick, hastened forward and arrived on the

battlefield in time to play a key part in halting Johnston's

advance.

|

IN A DESPERATE ACT OF HEROISM, COLOR SERGEANT HIRAM W. PURCELL OF THE

104TH PENNSYLVANIA SAVES HIS REGIMENT COLORS AT SEVEN PINES AS

CONFEDERATES RUSH FOR THE HIGHLY COVETED PRIZE. (COLLECTION OF THE

MERCER MUSEUM OF THE BUCKS COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

|

AS PART OF AN EFFECTIVE UNION COUNTERATTACK ON JUNE 1, THE 88TH AND 69TH

NEW YORK DROVE THE CONFEDERATES FROM THE FIELD, RECAPTURING GROUND LOST

THE PREVIOUS DAY. (FRANK AND MARIE WOOD PRINT COLLECTION)

|

The most important event of the day—perhaps of the

war—occurred near Fair Oaks Station late in the afternoon.

Johnston, who had been actively exhorting his troops since entering the

battle, suddenly reeled in his saddle, struck by a bullet and a piece of

shrapnel. Anguished aides carried him to Richmond and out of the

Peninsula campaign. With Johnston disabled, command of the army fell to

G. W. Smith, who was bedeviled by ill health and, so it seemed,

excessive caution. Davis felt he could not lay the fate of Richmond in

such uncertain hands and that night made his most important decision of

the war. Effective the next day, June 1, Robert E. Lee would command the

army in the field.

Before Lee assumed command at Seven Pines on June 1, the armies at

Seven Pines resumed the battle. The Confederates fended off Federal

attacks and ventured counterassaults that made no headway against fresh

Federal troops in strong positions. The fighting ended leaving 6,100

Confederates and 5,000 Federals killed, wounded, captured, or missing in

the two-day fight. It had been the bloodiest battle of the war in the

East to that point, and only the armies engaged at the Battle of Shiloh

in Tennessee on April 6 and 7 had killed or wounded more men than fell

at Seven Pines (or Fair Oaks as the Federals called it).

|

ALTHOUGH IN WORKING ORDER IN THIS PHOTOGRAPH, GRAPEVINE BRIDGE WAS

PARTIALLY SUBMERGED BY THE WATERS OF THE CHICKAHOMINY ON MAY 31, KEEPING

ELEMENTS OF EDWIN SUMNER'S SECOND CORPS FROM REACHING THE SEVEN PINES

BATTLEFIELD. (USAMHI)

|

|

UNION ARTILLERISTS POSE AT THEIR POSTS NEAR THE SEVEN PINES BATTLEFIELD.

(USAMHI)

|

Seven Pines marked the end of a phase in the Peninsula campaign. The

large, climactic battle Johnston had wished and McClellan had expected

had been attempted, but while Seven Pines had been large, it had not

been climactic. McClellan called the battle a victory, but his army had

been hurt and had very little to show for the win except that it had not

been destroyed. Confederate leaders had much more reason to be depressed

at the outcome of Seven Pines. Southerners had based their hopes of

saving Richmond and their young nation on the premise that Confederate

troops would at the moment of crisis somehow defeat the overwhelming

invading hordes in battle—but when the battle came, the Yankees had

survived. McClellan's army stood ready to resume its march on Richmond.

After Seven Pines, the already darkening future of the Confederacy

arguably took on a deeper hue of gloom.

|

|