|

Once again in this long campaign on the Peninsula, "Prince John"

Magruder found himself in the limelight. Three months had passed since

the Virginian had duped the Federals with theatrics at Yorktown. Now he

was at the heart of Lee's plan to crush McClellan's army. Unfortunately,

he was barely up to the task. Magruder had been ill and was taking

medication laced with opium. He could not relax enough to sleep and

seemed to some around him to be nearing the end of his endurance.

Nevertheless the decisive hour was at hand, and Lee expected Magruder to

do his duty. The general's orders were plain: press vigorously toward

Savage's Station.

Magruder moved forward with 13,000 men on Sunday morning, June 29 and

skirmished with Federals along the railroad. The Northerners, under

General Sumner, made a stand near a peach orchard at Allen's Farm on the

railroad but withdrew after delaying Magruder a couple of hours. The

Confederates pushed on, but as they neared Savage's, Magruder began to

grow apprehensive. Federal activity in his front convinced him he was

about to be attacked, and he asked Lee for reinforcements. Lee likely

discounted Magruder's fears but supported him with two extra brigades

anyway, stipulating that the brigades must be returned if not used

promptly. The Federal attack never came, and the two brigades trudged

wearily back to where they belonged.

|

MCCLELLAN BURNED BRIDGES, LIKE THIS ONE OVER THE CHICKAHOMINY RIVER, TO

STALL THE CONFEDERATE PURSUIT. (USAMHI)

|

Lee had hoped to squeeze the Federal position at Savage's with

pressure from Magruder on the west and Jackson on the north, but the

latter was again mysteriously slow in fulfilling his assignment. His

men worked to rebuild bridges over the Chickahominy, but the task took

much longer than expected, and Jackson seems not to have pressed his men

to get the job done with all haste. In the afternoon, Jackson received

a copy of a note from headquarters that he believed ordered him to hold

his position at the bridges. When an officer from Magruder's command

asked Jackson why he was not crossing the Chickahominy to attack

Savage's Station, Jackson replied that he had "other important duties to

perform." This puzzled both Magruder and Lee. The commanding general

said Jackson had made a mistake and should be advancing vigorously. But

the misunderstanding had gone too far to be reclaimed. Magruder was on

his own and advanced cautiously.

After Sumner had withdrawn his Second Corps troops from Allen's Farm,

he joined most of the Sixth Corps and Third Corps around Savage's.

McClellan had moved on toward the James with the rest of the army

without appointing anyone to command the rear guard, nor had he issued

any orders about deployment at Savage's. Sumner, the senior general

present, did not quickly grasp the developing tactical situation and

made no cohesive defensive deployment, but he would have little trouble

fending off Magruder's tentative thrusts at Savage's Station. The

Confederate sent only a few of his brigades forward into the woods and

fields west of the station, and Sumner would send only a few in

response. The Confederates, especially the brigades of Brigadier General

Joseph B. Kershaw and Brigadier General Paul J. Semmes, pressed on

gallantly, inflicting severe punishment and threatening to breach the

Federal line. Brigadier General William Burns's Philadelphians surged

forward to stem the tide, and reinforcements from the large Federal

reserve stifled all further Southern advances. When Brigadier General

William T. H. Brooks's Vermont brigade stormed into the woods toward

dusk, it ran smack into Semmes's men and Colonel William Barksdale's

Mississippians. For a short time, the fight in the darkening woods

matched anything Shiloh or Seven Pines or Gaines's Mill could boast in

the way of ferocity. "In less time than it takes to tell it," recalled

one of Brooks's men, "the ground was strewn with fallen Vermonters." The

5th Vermont lost 206 men, more than half its strength, in 20 minutes.

Among the fallen were five Cummings brothers, one of their cousins and

their brother-in-law. Six of the seven men were killed; only the eldest

brother, Henry Cummings, survived.

|

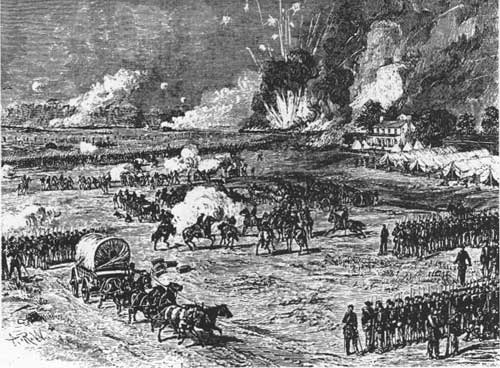

SAVAGE'S STATION BECAME A SMOLDERING RUIN. "THE SCENE WAS ALTOGETHER

UNEARTHLY AND DEMONIAC," WROTE AN OBSERVER. "THE WORKMEN SEEMED TO HAVE

A SAVAGE AND FIENDISH JOY IN CONSIGNING TO THE FLAMES WHAT A FEW DAYS

AFTERWARDS THEY WOULD HAVE GIVEN THOUSANDS TO ENJOY." (BL)

|

When the fighting stopped west of Savage's, almost 450 of Magruder's

men had become casualties. The South Carolinians of Kershaw's Brigade

got the worst of the fight, losing 290 men, and in a vain cause, for

Magruder had not accomplished his mission or attained any significant

strategic advantages. Later that night, Lee uncharacteristically

expressed his dissatisfaction with Magruder's lack of progress. The

commanding general saw that his opportunities to seriously harm the

Federals were slipping away and told Magruder "we must waste no more

time or he will escape us entirely."

That night held no rest for the Army of the Potomac. The men stumbled

onward though the black forests and endured the lashings of a violent

thunderstorm before dawn on June 30 found most of them south of White

Oak Swamp. McClellan met with some of his commanders at the nearby

Glendale intersection early in the day and issued broad orders to defend

the crossroads until all the trains, artillery, and the remainder of the

army had passed. The commanding general scattered seven divisions

around in a four-mile arc to cover Glendale, then left the field, riding

southward to the James and then taking a cutter out to the gunboat

Galena, where he would spend the rest of the day and part of the

next. Many in the army later felt McClellan had abandoned them. The

general claimed he intended to use the gunboat to scout the river and

find a safe haven for his army, but he had already assigned that task to

army engineers, and, in any event, it would seem that the commanding

general's presence would be of greater value with his men while they

awaited the approach of the enemy. McClellan had issued no specific

orders to any of his generals at Glendale and had assigned none of them

to overall command in his absence. "Bull" Sumner was again in command

by default, and the fight that day would be a clumsy, uncoordinated

effort to stave off repeated Confederate thrusts.

Stonewall Jackson at last crossed the Chickahominy early on the

morning of June 30 and moved through Savage's Station, where Lee ordered

him to continue pursuing the Federals by way of the bridge over White

Oak Swamp. The Valley general set off at once and with his more than

20,000 men made it to the swamp a little before noon, finding the bridge

destroyed and the Federals in strength on the south bank. Jackson

immediately deployed his artillery under cover of woods then opened a

terrific bombardment, the size and suddenness of which created havoc

for the Federals.

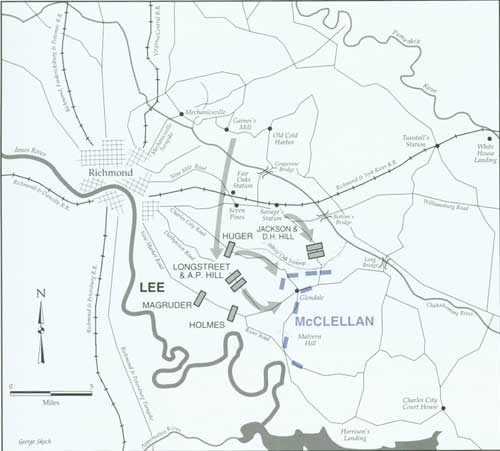

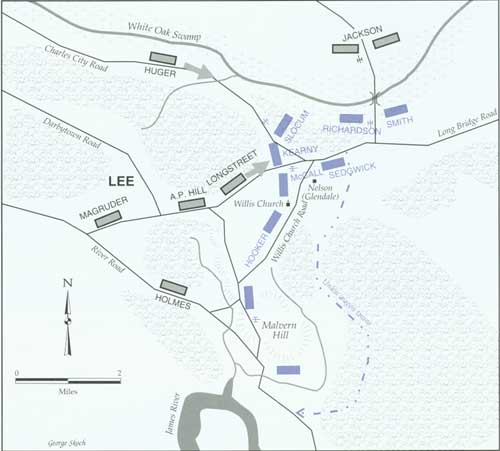

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

TROOP MOVEMENTS JUNE 28-30

Following the Confederate victory

at Gaines's Mill, McClellan ordered his entire army away from the

Chickahominy and toward the James. Lee quickly recognized the opportunity for

cutting off McClellan's retreat and defeating the widely scattered Union

forces. His plans called for a concentration of troops at the cross

roads near Glendale. On June 29 Confederate columns, following

different routes, marched toward the crossroads. The Union army found

itself in a precarious position, with soldiers scattered over ten miles

from the bridge at White Oak Swamp to the River Road leading to

Harrison's Landing.

|

"It was as if a nest of earthquakes had suddenly exploded under our

feet," wrote a Vermont soldier. Terrified men, horses, and mules dashed

about in confusion. The Federals arranged a few batteries to respond and

the affair settled into an artillery duel in which neither side had a

clear view of the other because of smoke and trees. Jackson permitted

the exchange to continue all day as his cavalry and ambitious

subordinate officers probed for ways to get across the swamp. Jackson

appears to have made no reasonable attempt to move his men across either

by force or by stealth, and, in fact, even found occasion for an

afternoon nap. Whatever the reason for Jackson's mysterious behavior at

White Oak Swamp, the effect was that the Federals on the south bank

conducted yet another successful rear-guard action. For the third time

in the five days of Lee's offensive, Jackson's troops would not get into

the day's fight.

|

STONEWALL JACKSON'S CONFEDERATES RAN INTO STIFF RESISTANCE AT WHITE OAK

SWAMP BRIDGE. POWERFUL UNION ARTILLERY BOUGHT EXTRA TIME FOR MCCLELLAN'S

RETREAT AND THE DEFENDERS AT GLENDALE. (BL)

|

|

GLENDALE OR FRAYSER'S FARM?

Having multiple names for the same battle remains one of the war's

more interesting curiosities. Explanations are just as varied. One old

story goes, "Well, northerners and southerners couldn't agree on much,

so why should they agree on what to name the battles." Whatever the

reason, this habit, popularized at Bull Run or Manassas, continued

indiscriminately throughout the war.

The 1862 actions before Richmond certainly lived up to the tradition

with the likes of Seven Pines (Fair Oaks), Oak Grove (King's School

House), Beaver Dam Creek (Mechanicsville), and Gaines's Mill (Cold

Harbor) making their way into the correspondence. But no battle of the

war goes by more names than the one fought on June 30, 1862. Union

reports generally referred to the action as Glendale while Confederate

writers preferred Frayser's (commonly misspelled Frazier's), Farm. Those

two are just the beginning.

|

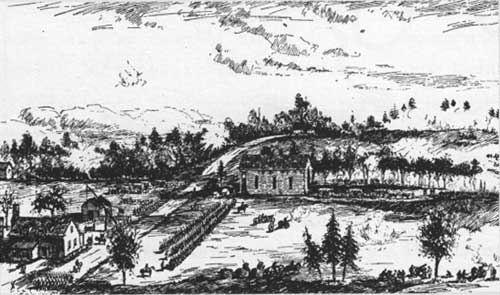

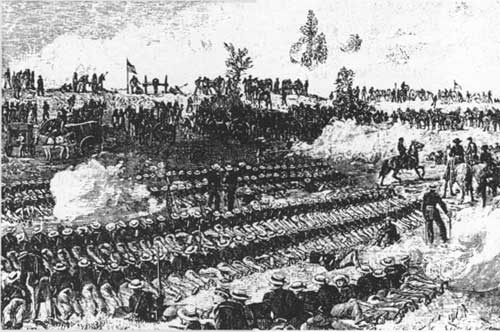

THIS PERIOD SKETCH FEATURED THE BATTLEFIELD LANDMARKS WILLIS METHODIST

CHURCH, WILLIS CHURCH ROAD, AND NELSON'S FARMHOUSE. (BL)

|

Many think Glendale referred to a small community or the important

crossroads. It was neither. Instead Glendale was the wartime home and

property of the R. H. Nelson family. The Nelson farm had belonged to the

Frayser family, but that was before the war began. A popular theory has

it that when the soldiers asked the locals to name the fields they had

fought on, many still called it Frayser's even though the family had

long since moved away. Regardless, both Frayser and Nelson appear

frequently in soldiers' after-action accounts.

The crossroads where the Long Bridge, Charles City, and Willis Church

(or Quaker) Roads came together had several names. On one corner stood

Riddell's Shop, a blacksmith business, that was used repeatedly as a

battlefield reference. Just as often, though, soldiers used the major

roads to name the intersection. Hence many reported on June 30 as the

Battle of Charles City Crossroads.

Willis Methodist Church, a battlefield landmark, also lent its name

to the day's events. Then, too, many confused the nearby New Market Road

with the Long Bridge Road, adding two more battle names to the list. In

a perverse twist, the Whitlock farm, site of repeated attacks on June

30, rarely turns up in accounts.

The soldiers who fought over this nondescript landscape knew it by

many names. Whatever the name, this now quiet country crossroads will be

forever remembered for the deeds of others long ago.

|

About two miles to the west of the stalemate at White Oak Swamp,

Lee's other two attacking columns—one under Benjamin Huger and a

larger force composed of A. P. Hill's and Longstreet's divisions, tried

to move directly on Glendale. Huger, slowed by trees felled across the

road and blocked by Federal artillery and a division of infantry under

Brigadier General Henry Slocum, could make little headway on the Charles

City Road. To the south, a small column on the River Road under General

Theophilus H. Holmes recoiled before massed Federal artillery and fire

from gunboats. As the afternoon wore on, Lee realized that his plan to

interdict the Federal retreat had gone awry and that the only hope of

damaging the Federals lay with Longstreet's column on the Long Bridge

Road. About 4 P.M., Lee ordered Longstreet into the fight.

Longstreet attacked with his own and A. P. Hill's men on both sides

of the Long Bridge Road. In position to meet the assault were Hill's

adversaries from Beaver Dam Creek and Gaines's Mill, the Pennsylvanians

of George McCall's division. Hill's and McCall's men had already done

more fighting that week than any other troops, and they deserved the day

off, but fate threw them together on the Long Bridge Road in what would

be perhaps the most savage fighting of that week of battles.

|

DETERMINED SOLDIERS, LIKE THESE FROM WILLIAM F. "BALDY" SMITH'S

DIVISION, HELPED FEND OFF LEE'S ARMY ON JUNE 30. (BL)

|

Twenty-four field guns from six batteries—New Yorkers,

Pennsylvanians, and U.S. Regulars—held the crest of a shallow rise

above a ravine southwest of Glendale. The artillery presented a formidable

front, made even more fearsome by McCall's 6,000 men and Phil

Kearny's 7,500 infantrymen. Nearby in reserve stood two more divisions

of Federal infantry under Sam Heintzelman and Sumner, plus several

batteries. But Longstreet's men seemed possessed by a powerful

determination and lunged forward with almost irresistible recklessness.

"But a single idea seemed to control the minds of the men," wrote

Brigadier General James L. Kemper of his brigade's advance, "which was

to reach the enemy's line by the directest route and in the shortest

time; and no earthly power could have availed to arrest or restrain the

impetuousity with which they rushed toward the foe."

|

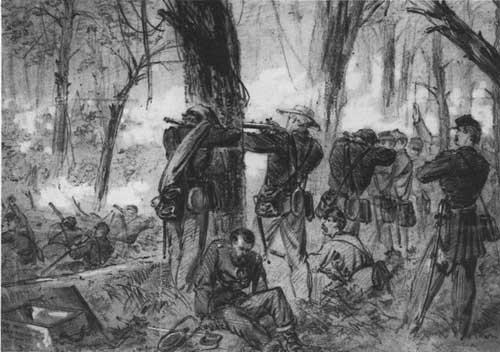

MEN OF PHILIP KEARNEY'S DIVISION

FIGHTING IN THE WOODS ABOVE GLENDALE. (LC)

|

Kemper's Virginians shattered McCall's left flank, then had to

withdraw because supports did not come forward quickly enough. But

McCall's line had been broken and would never quite be restored in the

seesaw fighting through the rest of the afternoon. Longstreet's six

brigades and Hill's six repeatedly charged against McCall and Kearny,

occasionally breached McCall's line, then reeled back under the force of

counterattacks. The climax of the fighting came near sunset when

Alabamians under Brigadier General Cadmus M. Wilcox captured the six-gun

battery of Lieutenant Alanson Randol on the Long Bridge Road. The

Pennsylvanians, joined by an enraged Randol and his gunners,

counterattacked and retook the guns in more hand-to-hand fighting. But

Virginians under Brigadier General Charles W. Field took the battery

back and held it. General McCall, wounded but still riding through the

darkening forest to shore up his lines, wandered into the ranks of the

47th Virginia and went to Richmond the next day as a prisoner. McCall's

survivors and their supports helped Kearny's stalwart veterans hold the

line until the Confederates ceased their attacks well after 9 P.M.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

BATTLE OF GLENDALE, JUNE 30

Lee's plan to concentrate the

army and control the vital crossroads near Glendale never materialized.

Stonewall Jackson's advance stalled at White Oak Swamp against two Union

divisions. They spent the day exchanging artillery fire. Artillery and

felled trees blocked Benjamin Huger's march along the Charles City

Road. Major General Holmes provided scant support along the River Road.

Only the divisions of James Longstreet and A. P. Hill reached the

battlefield. Once there they met stubborn resistance from five Union

divisions. In a bitter, sometimes hand-to-hand, struggle men fought one

another with clubbed muskets and bayonets. Darkness brought the action

to a close. The road to the James remained open.

|

Soldiers remembered the fighting at Glendale for its savagery. "No

more desperate encounter took place in the war," wrote Confederate E. P.

Alexander, "and nowhere else, to my knowledge, so much actual personal

fighting with bayonet and butt of gun." The Federals had spent some

2,800 men in defending the army's retreat route. The Confederates had

expended 3,600 in their failed attempt (which they referred to as the

Battle of Frayser's Farm) to cut the Army of the Potomac to pieces.

|

THE FEDERAL PERSPECTIVE AT GLENDALE

Some of the most ferocious fighting of the campaign occurred on June

30 at Glendale (Frayser's Farm). The 7th Pennsylvania Reserves were in

the thickest of the action. This excerpt is from a postwar account by a

member of that regiment, describing an early phase of the

battle.

Suddenly a Confederate regiment . . . charged in mass from the black

jacks at [the] lower end of the pines, crossing the "breast works" which

we had so hastily constructed and from which we had been ordered

rearward. They move on a run across Randall's muzzles as though to pass

round to his left. But Captain Cooper's battery is on the left of the

regulars, Randall's men cease their shell fire at first sight of the

charging column, quickly depress their muzzles, load grape and canister,

and "let go."

The merciless guns roar in quick succession, and the carnage . . .

has begun. Oh that terrible afternoon of June 30, 1862. 'Tis always

foremost in my memory of the seven days' battle. The enemy is within

easy musket range, and fires a few shots directed on the battery, which

seemed like kicking against a whirlwind, or trying to stop a mountain

torrent. Many of them are seen to fall in the clouds of dust being

raised by the grape shot striking the parched ground . . . . As we

looked upon them and waited for some word of command it seemed they did

not know what to do about it, that they were in the wrong place and

disliked the idea of "getting out." Our gunners slammed into them with

rapidity. The ground was somewhat depressed on the battery front, and

in order that the canister might produce more havoc the muzzles were

held well down thus lifting the gun wheels from the ground at every

discharge.

|

EARLY FIGHTING AT GLENDALE CENTERED ON THE CHARLES CITY ROAD. THE STRAW

HATS WORN BY THE 16TH NEW YORK INFANTRY CAUGHT ONE ARTIST'S EYE.

(BL)

|

Col. Harvey commanded "Charge, seventh regiment." We moved away in

almost solid mass . . . . As we advance, sounding the charge yell, we

see the enemy surging slightly, but heavily, as a mighty wave, the

deadly fire of the artillery still pouring into them. They seem, so to

speak, to find their level, somewhat after the manner of a large body

of water suddenly shot into a reservoir or other inclosure, then suddenly

move as water that has found a large outlet, back by the way they had

advanced . . . .

The artillery slewed their guns to the right to follow the enemy as

we made way for them, until they now fired into the pines . . . . the

canister, at every discharge, barked the trees, smacking off patches as

large as one's hand from two to six feet from the ground, thus suddenly

exposing the white wood, reminding one of the illuminings of numerous

very large fire bugs on the tree trunks . . . . I saw about 100 feet in

rear, a young pine some thirty feet tall, knocked off by our canister

about five feet from the ground, the trunk being carried suddenly

forward and upward. The tree fell on its top; the stem pointing upward

for an instant then falling over.

Holmes Alexander

Hummelstown (Pa.)

Sun, 1894

|

|

THE CAPTURE OF RANDOL'S UNION BATTERY EPITOMIZED THE CLOSE-QUARTERS

FIGHTING AT GLENDALE. (BL)

|

|

|