|

That Thursday morning, June 27, must have found Robert E. Lee pleased

with the progress of events. His plan, though still behind schedule, was

unfolding satisfactorily, and both his army and part of McClellan's were

moving in the direction he wished—down the Chickahominy. But Lee

was far from being content and knew that his troops must keep the

pressure on Porter's men if the Federals were to be forced from the

north bank of the Chickahominy. Again this day Jackson's command would

play the crucial part in the plan. He was to continue his march to Old

Cold Harbor, still moving along the Federal right flank. As Lee saw it,

the Federals, aware now of Jackson's presence, had two choices: they

could prepare to meet Jackson when he arrived on their flank and rear at

Old Cold Harbor or they could abandon altogether their positions north

of the Chickahominy. Lee hoped it would be the latter. He met with

Jackson at Walnut Grove Church and, as the army's columns pressed by in

dusty pursuit, informed his general that D. H. Hill's large division

would march with the Valley army and be under Jackson's command. The two

men parted, Jackson to move his men onward—they had marched about

10 miles already that morning and would have to cover another eight to

be in position at Old Cold Harbor—and Lee to join A. P. Hill's and

Longstreet's columns pursuing in the Federals' wake toward Gaines's

Mill. If all went well, Lee would have all 60,000 men of his attacking

force in position to fight by early afternoon.

|

THE ADAMS HOUSE STOOD BEHIND THE UNION LINES AT GAINES'S MILL. HUNDREDS

OF WOUNDED SOUGHT RELIEF IN AND AROUND THE HOUSE. NEAR DUSK WHILE THE

FEDERALS RACED TOWARD THE CHICKAHOMINY, RESERVE UNION BATTERIES

POSITIONED NEAR THE HOUSE FELL INTO CONFEDERATE HANDS. (USAMHI)

|

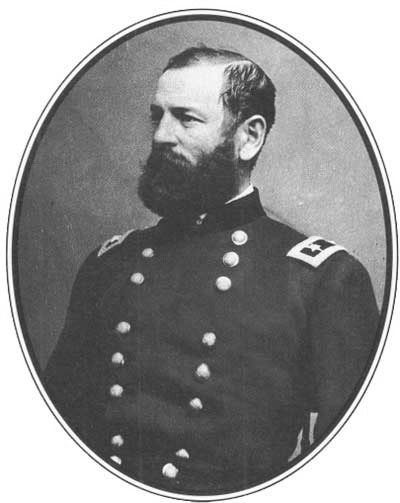

But Fitz John Porter, a brave and capable officer, did not rattle

easily. He and his friend McClellan had spent the night of June 26

discussing the situation of the army, and Porter understood that he was

to be entrusted with fulfilling a crucial assignment. McClellan had

decided the time had come to let go of his supply line—the Richmond

& York River Railroad—and move toward the James to establish a

new base. This would be a dangerous operation in the presence of a large

and aggressive enemy, but faced with the choice of standing and fighting

or changing his base, McClellan decided the retrograde movement was the

better option. He needed time to move the army, its 3,000 wagons, heavy

guns of the artillery reserve, the sick and wounded, the 2,500 head of

beef, and countless tons of supplies, and Porter and his men would buy

that time. If they failed, the army might be destroyed.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

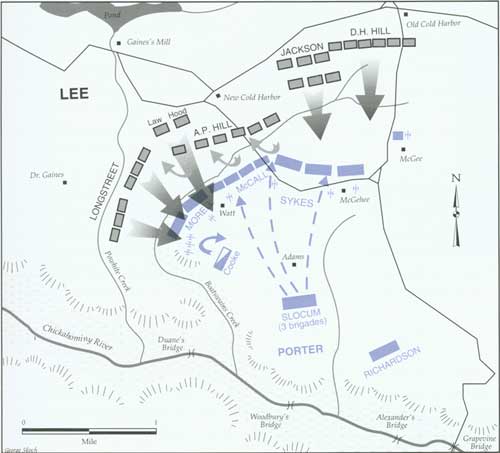

BATTLE OF GAINES'S MILL, JUNE 27

Confederate attacks began

shortly after noon when A. P. Hill's brigades charged the Union center

held by Brigadier General George Sykes's division of Porter's V Corps.

The battle reached its climax shortly after 7:00 P.M. when Lee's

combined forces surged forward against the entire Union line. Several

break-throughs occurred simultaneously. A last desperate attempt to save

several artillery pieces from capture failed when Brigadier General

Philip St. George Cooke's cavalry charged straight toward Hood's men. A

volley of musketry quickly dispersed the riders.

|

Reinforced to a strength of 35,000 men, Porter formed his defense on

high ground east of Gaines's Mill and behind Boatswain's Creek. Like the

line at Beaver Dam Creek, this naturally strong position rose to wooded

heights that dominated a boggy creek bottom, but Porter's men made it

even stronger by felling trees and digging rifle pits on the steep slope

and placing batteries along the top of the hill. For the second

consecutive day, the Federals had a great advantage in a dominating

defensive position.

A. P. Hill's men began the action around 2:30 P.M., testing Porter's

position near New Cold Harbor. Hill later reported that "the incessant

roar of musketry and the deep thunder of the artillery" told him that

the Federals were before him in great strength. His men, the general

wrote, "met a withering storm of bullets, but pressed on to within a

short distance of the enemy's works, but the storm was too fierce . . .

they recoiled and were again pressed to a charge, but with no better

success. These brave men had done all that any soldiers could do." The

Federals repulsed all Confederate sallies throughout the afternoon, and

hundreds of men, Union and Confederate, fell on the slopes above the

creek bottom.

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL FITZ JOHN PORTER (USAMHI)

|

|

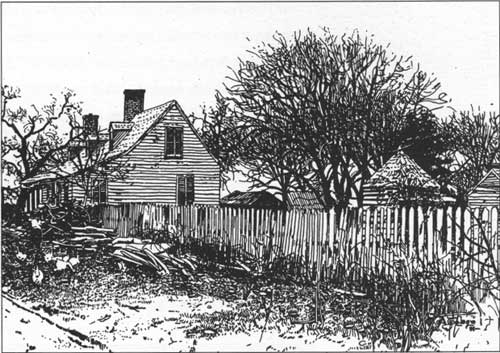

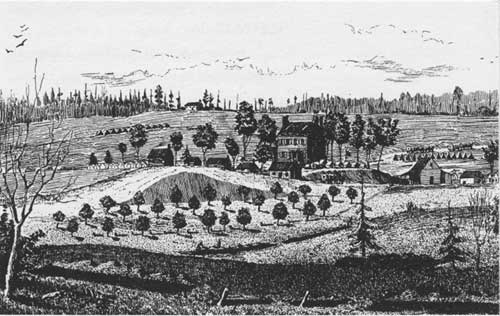

THE JUNE 27, 1862, BATTLE TOOK ITS NAME FROM THIS PROMINENT LOCAL

STRUCTURE, GAINES'S MILL, THAT ACTUALLY STOOD NORTH OF THE BATTLEFIELD.

UNION GENERAL PHILIP SHERIDAN'S CAVALRY BURNED THE MILL DURING AN 1864

RAID. (USAMHI)

|

Daylight waned, and Lee had yet to crack the Federal line. Though A.

P. Hill and Longstreet had been feeding men into the fight all

afternoon, they had made no substantial progress. Much to the

commanding general's frustration, Longstreet and Hill lacked support from

the left end of the Confederate line. For the second time in two days,

Stonewall Jackson was late.

Lacking good maps and led by a guide who misunderstood his

instructions, Jackson had taken a wrong road and lost precious time.

Only late in the afternoon did his men reach Old Cold Harbor and deploy

for battle. At 7 P.M., Lee ordered a general assault, and soon

thereafter, Confederate infantry advanced along a two-mile front. The

persistent Southerners pressed in on the outnumbered Federals at every

point along the line. The firing was terrific, producing a deafening

roar and clouds of smoke that one Texan swore blocked out the sun.

Finally, as the sun was setting, portions of Porter's line began to

give way. Brigadier General John Hood's "Texas Brigade" broke through at

Boatswain's Creek, and, on the far eastern end of the line, Jackson's

men breached the Federal defense near the road to the Chickahominy.

Despite heroic resistance in some places, especially by the U.S. Regular

troops opposing Jackson, Porter's line began to crumble. In desperation,

cavalry commander Philip St. George Cooke ordered a cavalry charge

intended to throw the advancing Confederates off balance long enough for

Federal infantry and artillery to escape. Cooke's charge failed, and the

Federals lost 22 cannon and thousands of prisoners in the

withdrawal.

|

ONE FAMILY'S WAR

Among the hundreds of civilians to feel the effects of invasion and

war on the Peninsula the family of Hugh Watt stands out. Mr. Watt and

his wife, Sarah, had operated a prosperous farm on the north bank of the

Chickahominy River. Their modest plantation home Springfield was built

in the early 1800s.

In the early afternoon of June 27, 1862, the Battle of Gaines's Mill

erupted on the Watt Farm. The 77-year-old Mrs. Watt (by that time a

widow) had been very ill for several weeks. As the first shells crashed

into the stable and kitchen chimney, Union officers warned the family to

leave quickly. Mrs. Watt protested feebly, but her children hastily

moved her off to safety. One of her grandchildren recorded later that

Mrs. Watt's condition had "benumbed her faculties," thus softening the

anguish of departing the family farm. The largest battle in the history

of Virginia up to that point was about to explode on her farm.

The Watts joined a procession of at least forty other displaced

locals fleeing eastward beyond the borders of the battlefield,

Occasionally some badly aimed shell would explode nearby, adding to the

chaos. The refugees gathered together in small groups and listened to

the battle "with bowed heads and tearful eyes."

At twilight, the final Confederate surge of the battle swept through

the yard of the Watt House and beyond, leaving a trail of dead and

wounded soldiers mixed with shattered wood from the house and its

outbuildings. Victorious Confederates soon began to segregate the

wounded, removing the injured Northerners they found into and around

the house. One week later a Confederate surgeon reported 400 wounded

still at the house. Supplies had dwindled, leaving the miserable

collection of wounded "entirely unprovided for."

|

SARAH BOHANNON KIDD WATT (COURTESY OF ELIZABETH DEANE HAW HOBBS)

|

A visitor to the area in September noticed graves all over the yard,

even in Mrs. Watt's garden. The house stood grimly silent, "The walls

and roof . . . torn by shot and shell, the weather-boarding honeycombed

by minnie balls, and every pane of glass shattered." Every piece

of floor inside the house bore menacing bloodstains. "Once a neat and

comfortable home now a . . . foul and battered wreck," the visitor

concluded.

Mrs. Watt was spared the ugliness of the scene. Her condition

continued to deteriorate, and she died early the following year,

apparently without having returned home. In some ways Sarah Watt is

similar to the famous Widow Henry at the Battle of First Manassas.

Although Mrs. Henry died in more violent circumstances, they both

illustrate the arbitrary heavy hand of the Civil War that doled out

destruction to soldier and civilian alike.

|

The Battle of Gaines's Mill was a clear Confederate victory. Porter's

force, outnumbered for much of the day, had held its own but at a

fearful cost—about 6,000 Northerners killed, wounded, missing, or

captured in seven hours of fighting. Lee had won his first battlefield

victory at the steep price of 9,000 men. With almost 95,000 men engaged,

Gaines's Mill was larger and costlier than Seven Pines and established a

new standard for blood-letting in the eastern theater. Though the two

armies that had battled at Shiloh several weeks before had produced

almost 25,000 casualties in two days of fighting, Lee and Porter had

together lost 15,000 in a single afternoon.

|

STONEWALL JACKSON'S TROOPS MARCHED PAST OLD COLD HARBOR TAVERN ON THEIR

WAY TO BATTLE ON JUNE 27. (BL)

|

|

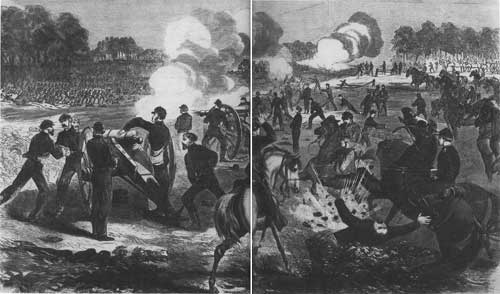

THE FINAL EFFORT BY PORTER'S DEFENDERS AT GAINES'S MILL WAS A DESPERATE

CAVALRY CHARGE. ARTIST WILLIAM TREGO MEMORIALIZED THE DRAMATIC TWILIGHT

SCENE IN THIS POSTWAR PAINTING. (LC)

|

McClellan saw the battle for the disaster it was, and he was ready to

point the finger of blame. Throughout the campaign, the general had

been pleading with Washington to send him reinforcements. He had

reported (incorrectly) that the Confederates outnumbered him

overwhelmingly and that his army was in great danger if not strengthened.

Now, the doom he had foretold had become reality, and he was quick to

blame it on Lincoln and the War Department.

"I have lost this battle because my force was too small," he wrote in

a midnight letter just hours after the firing stopped. "I again repeat

that I am not responsible for this, and say it with the earnestness of a

general who feels in his heart the loss of every brave man who has

needlessly been sacrificed to-day. . . . You must send me very large

reinforcements, and send them at once, . . . As it is, the government

must not and cannot hold me responsible for the result."

|

A PERIOD DEPICTION OF THE FIGHTING AT GAINES'S MILL. SIMILAR

"GLAMORIZED" DRAWINGS ILLUSTRATED POPULAR WARTIME MAGAZINES SUCH AS

HARPER'S WEEKLY AND LESLIE'S.

|

The general then got to the heart of the matter, He felt his

political enemies in Washington, among whom he numbered Secretary of War

Edwin M. Stanton, had conspired to bring about his failure. "I feel too

earnestly to-night," the general wrote, "I have seen too many dead and

wounded comrades to feel otherwise that the government has not sustained

this army. If you do not do so now the game is lost, If I save this army

now, I tell you plainly that I owe no thanks to you or to any other

persons in Washington. You have done your best to sacrifice this army."

A startled communications officer in Washington deleted the final two

sentences before delivering the telegram to Stanton.

If McClellan's intemperate and insubordinate "I-told-you-so" letter

was intended to send chills of fear through Lincoln and Stanton, it

worked. Lincoln immediately responded with a kind, supportive note,

assuring the general that the government would do everything possible to

forward reinforcements, but that McClellan must do his best in the meantime

to save the army.

McClellan was justified in his complaints to the extent that

Washington had not been patient during the three months he had been on

the Peninsula and had repeatedly badgered him to move more quickly on

Richmond. From the Lincoln administration's point of view, however, the

campaign was an enormous drain on the Federal treasury, and Lincoln,

Stanton, and their military advisers seem to have lost confidence in

McClellan as the weeks dragged on. There seemed to be no end in sight.

Furthermore, though the Lincoln administration had withheld troops from

McClellan, they had also reinforced him by almost 40,000 men between

April and mid-June.

|

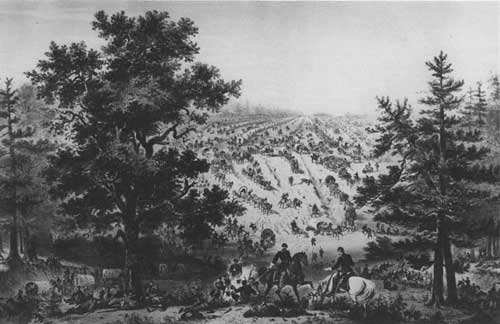

ONCE MCCLELLAN'S RETREAT BEGAN, NEARLY EVERY ROAD BETWEEN THE

CHICKAHOMINY AND JAMES RIVERS WAS CLOGGED WITH MOVING MEN AND WAGONS.

(LC)

|

McClellan's plan for saving his army was complex. First, the supply

officers had to relocate the enormous depot from White House Landing on

the Pamunkey to an as-yet-undetermined point on the James River. Federal

engineers searched for a site for the new depot even as the

quartermasters packed up the old one. McClellan intended for his army to

move rapidly from the Chickahominy over some 14 circuitous miles of

narrow, country roads through dense forests to the James. He sent the

Fourth Corps ahead to secure important points, especially the bridge

over White Oak Swamp and the crucial crossroads of Glendale, through

which most of the army must pass. Fitz John Porter's battered Fifth

Corps would follow the Fourth Corps and move on to the James. Meanwhile,

the three other corps that had remained south of the river—the

Second, Third, and Sixth, about 42,000 men total—would hold their

positions around Seven Pines and Savage's Station and cover the retreat

(McClellan declined to call the movement a retreat. Instead, he cast the

sidling march to the James in a positive light and referred to it as a

"change of base," as though it were merely another component of his

offensive operations against Richmond). McClellan calculated that he

would need two days—all of June 28 and 29—to get the lead two

corps and all of his impedimenta (wagons, wounded, cattle, and so on)

across White Oak Swamp, which he hoped would offer some measure of

protection.

|

THE CONFEDERATE PERSPECTIVE AT GAINES'S MILL

The Battle of Gaines's Mill was the largest of the Seven Days'

battles. The following graphic account, excerpted from a letter written

by an unidentified member of the 4th Texas Infantry, captures one man's

battlefield experience. It was published the month after the battle in

one of the Richmond newspapers.

"Suddenly, we (4th Texas Regiment) faced to the front, advanced in a

run up the hill, and as we reached the brow, were welcomed with a storm

of grape and canister from the opposite hill side, while the two lines

of infantry, protected by their works, and posted on the side of the

hill, upon the top of which was placed their battery, poured deadly and

staggering volleys full in our faces. Here fell our Colonel, John

Marshall, and with him, nearly half of his regiment. On the brow of this

hill the dead bodies of our Confederate soldiers lay in numbers. They

who had gone in at this point before us, and had been repulsed, stopped

on this hill to fire, and were mowed down like grass and compelled to

retire. It was now past 5 o'clock. When we got to the brow of this hill,

instead of halting, we rushed down it, yelling, and madly plunged right

into the deep branch of water at the base of the hill. Dashing up the

steep bank, being within thirty yards of the enemy's works, we flew

towards the breastworks, cleared them, and slaughtered the retreating

devils as they scampered up the hill towards their battery. There a

brave fellow, on horseback, with his hat on his sword, tried to rally

them . . . leaping over the work, we dashed up the hill, driving them

before us and capturing the battery.

|

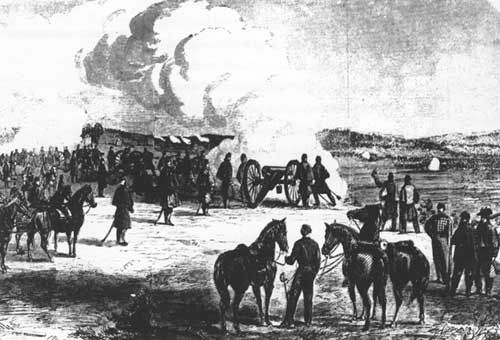

UNION ARTILLERY SHELLING CONFEDERATE INFANTRY AT GAINES'S MILL.

(HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

. . . . we saw there was yet work ahead. We were now in an open field

. . . a heavy thirty-two pound battery straight ahead now opened on us

with terrible effect, while another off to the right reminded us that

we had just commenced the battle. On we go . . . exposed to a galling

fire from the battery in front, from that on the right, and from swarms

of broken infantry all on our left and rear. Yet on, on we go, with not

a field officer to lead us, two thirds of the Company officers and half

the men already down—yelling, shouting, firing, running straight up

to the death-dealing machines before us; every one resolved to capture

them and rout the enemy . . . I could plainly see the gunners at work;

down they would drive the horrid grape—a long, blazing flame

issued from the pieces, and then crashing through the fence and barn,

shattering rails and weather-boarding, came the terrible missiles with

merciless fury . . . The smoke had now settled down upon the field in

thick curtains, rolling about like some half solid substance; the dust

was suffocating. We could see nothing but the red blaze of the cannon,

and hear nothing but its roar and the hurtling and whizzing of the

missiles. Suddenly the word is passed down the line, "Cavalry," and down

come horses and riders with sabres swung over their heads, charging like

an avalanche upon our scattered lines; they were met by volleys of lead,

and fixed bayonets in the hands of resolute men, and in less time that I

take to write it, a squadron of U.S. Regular Cavalry was routed and

destroyed. Horses without riders, or sometimes with a wounded or dead

master dangling from the stirrups, plunged wildly and fearfully over

the plain, trampling over dead and dying, presenting altogether one of

the most sublime and at the same time fearful pictures that any man can

conceive of without being an eyewitness . . . .

The next morning we arose early. I will not attempt to describe the

appearance of the field. I could write twenty pages and yet give you no

adequate idea of it."

Richmond Daily Whig

August 4, 1862

|

So far, Lee had been completely successful in his goal of driving

McClellan from Richmond. Not only had he delivered the capital from the

imminent threat of the siege, but he had wrested the initiative from

McClellan. Lee was now deciding the course of events, and McClellan, on

the defensive, was reacting to the Confederate's moves. Lee had reversed

the pattern of the past three months in just two days.

But the Confederate commander was not satisfied to rest upon these

accomplishments. He saw that now an even greater opportunity for

success lay before him. The defeated and battered enemy was in

flight—a circumstance every aggressive fighter hopes for, and Lee

was no exception. He believed that if he pursued McClellan and could

again strike him a hard blow, he might stand a very good chance of

destroying the Federal army, or at least a large portion of it. Lee did

not intend to permit McClellan to escape.

|

SAVAGE'S STATION ON THE RICHMOND AND YORK RIVER RAILROAD. (BL)

|

|

SAVAGE'S STATION SERVED AS MCCLELLAN'S MOST ADVANCED SUPPLY DEPOT.

(USAMHI)

|

But first, Lee had to be sure of where McClellan was retreating to.

The Federals might go to the James or they might move eastward toward

White House or even Fort Monroe. The Virginian spent anxious hours on

June 28 waiting for word from his scouts, but late in the day came

evidence to convince him that McClellan was heading southward. Lee at

once began planning to intercept and attack the Army of the Potomac

somewhere between the Chickahominy and the James.

According to Lee's new plan, Magruder, who had been holding the

Confederate line south of the Chickahominy with 23,000 men against

McClellan's approximately 58,000, was to move aggressively along the

Williamsburg Road-York River Railroad corridor toward Savage's

Station. Benjamin Huger, with his 9,000 men, was to move along

Magruder's right flank on the Charles City Road and push toward what Lee

saw was the crucial intersection at Glendale. Longstreet and A. P. Hill

with 20,000 men total, were to make a long march westward toward

Richmond then southward and eastward on the Darbytown Road heading, like

Huger, for Glendale. Jackson's column, including D. H. Hill's command,

was to cross the Chickahominy and follow directly in McClellan's

wake.

|

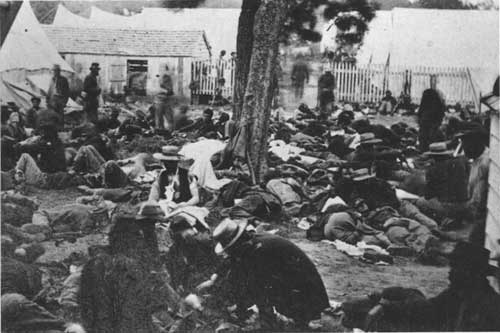

UNION WOUNDED AT SAVAGE'S STATION AFTER BATTLE ON JUNE 27. (USAMHI)

|

Savage's Station had been a Federal supply depot since just before

the Battle of Seven Pines. McClellan's quartermasters had accumulated

enormous amounts of food and equipment at the depot, and now, as the

army began its retreat, the supply officers realized they could not

remove everything. On June 28, the work of destruction began.

Pennsylvania chaplain J. J. Marks wrote, "No language can paint the

spectacle. Hundreds of barrels of flour and rice, sugar and molasses,

salt and coffee, were consigned to the flames; and great heaps of these

precious articles in a few moments lay scorching and smoldering. A long

line of boxes of crackers, fifteen feet high, were likewise thrown into

the mass."

While the destruction continued, a far sadder story began to unfold.

Savage's Station also served as a Federal field hospital. After the

battles of June 26 and 27, some 1,500 wounded men flooded into the

hospital at Savage's, and more continued to arrive until more than

2,500 men lay in and around the tents at the depot. The surgeons were

overwhelmed, as, apparently, was General McClellan. Though he had just

hours earlier told the president in lavish rhetoric that he "feels in

his heart the loss of every brave man who has needlessly been

sacrificed" McClellan decided he could not evacuate the wounded and

would abandon them to the mercy of the enemy.

|

|