|

Lee fretted for a while on the night of the twenty-fifth that

McClellan's advance at Oak Grove had been a spoiling attack. On the

morning of the twenty-sixth, Lee wrote to Davis: "I fear from the

operations of the enemy yesterday that our plan of operations has been

discovered to them." But by the time he turned in on the night of the

twenty-fifth, Lee had already made his decision to proceed with his

plan—it would not be ruined by McClellan's foray. Lee went to bed

believing that the situation was well in hand and tomorrow would see

the first step in the deliverance of Richmond.

|

PAINTING BY ARTIST SIDNEY KING OF CONFEDERATE GENERAL ROBERT E. LEE

FLANKED BY GENERALS LONGSTREET AND D. H. HILL AT THE OPENING BATTLE OF

THE SEVEN DAYS' CAMPAIGN. (NPS)

|

June 26 dawned pleasant, but as Lee prepared to move to the

battlefield, he received displeasing news: Jackson sent word that he was

far behind schedule. He said he would have his command up and on the

road earlier than planned, but Lee knew Jackson would be unable to be at

his assigned place on time. The commanding general could only hope

Jackson would move as rapidly as possible and make up much of the lost

time. Lee joined Longstreet's column on the dusty Mechanicsville

Turnpike to wait and from bluffs above the Chickahominy watched Federal

pickets in and around the hamlet of Mechanicsville on the other side of

the river. The generals listened for the sounds of firing from A. P.

Hill's front two miles upstream signaling the arrival of Jackson, but

the air hung heavy, hot, and silent.

Around 10 A.M., Lawrence Branch, waiting farther upstream from Hill's

position, received a note from Jackson and learned that the Valley army

was still behind schedule but was at last crossing the Virginia Central

Railroad into the day's area of operations. Jackson had not begun his

day's march as early as he had hoped to and once on the road had

encountered fallen trees, enemy skirmishers, and other obstacles thrown

in his path by Fitz John Porter's men. The result was that only by late

morning on the twenty-sixth was Jackson reaching the place he was to

have camped on the night of the twenty-fifth. By the most generous

estimate, Jackson was more than four hours—about 12 miles—behind

where he should have been.

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

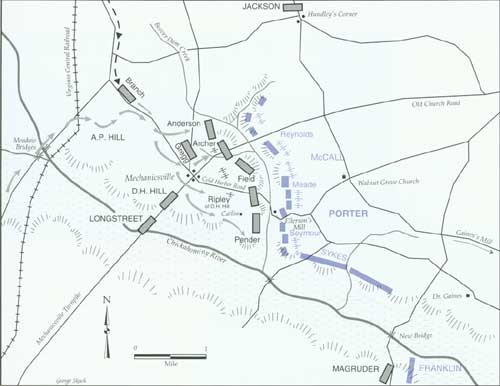

SEVEN DAYS' BATTLES: DAY TWO—JUNE 26, BATTLE OF BEAVER DAM

CREEK

After waiting in vain for word from Stonewall Jackson,

Brigadier General A. P. Hill put Lee's battle plan into motion by

crossing the Chickahominy River at Meadow Bridges. Skirmishing quickly

developed as Hill's brigades drove through Mechanicsville. Meanwhile,

Brigadier General George McCall's division of Pennsylvania Reserves

occupied previously built fortifications behind Beaver Dam Creek. Despite

repeated attempts, Union infantry and artillery repulsed each effort to

break their lines. That evening McClellan ordered a withdrawal. The next

day Brigadier General Fitz John Porter and the V Coops held an equally

strong position behind Boatswain's Creek.

|

Having at last heard from Jackson, Branch crossed the Chickahominy

and headed for Mechanicsville in execution of his part of the plan, but

his brigade of North Carolinians would not get into the fight that day,

nor would Jackson's 18,500 Valley troops. The man who initiated the

battle on June 26 had tired of waiting for Jackson and Branch and, in

his own words, "determined to cross [the Chickahominy] at once rather

than hazard the failure of the whole plan by longer deferring it."

Thirty-six-year-old A. P. Hill, youngest of Lee's division commanders,

was restless by nature, and by 3 P.M. he was out of patience. Having

heard from neither Jackson nor Branch, he ordered his men to force a

crossing at Meadow Bridges. The vastly outnumbered Federal pickets gave

way, and Hill pushed on to Mechanicsville.

Lee, watching from the bluffs above the Chickahominy saw Confederate

troops enter the village and exclaimed "Those are A. P. Hill's men." Lee

had intended that there be no real fighting at Mechanicsville. Jackson's

force should have outflanked the Federals at Mechanicsville by late

morning or early afternoon, and the Northerners should have withdrawn of

their own volition, but here was Hill forcing his way through against

stronger-than-expected resistance. Lee rode forward to learn what had

gone wrong with the plan.

Hill still expected Jackson to make an appearance above the

headwaters of Beaver Dam Creek, so he focused his attacks on the Federal

right flank. He sent Brigadier General Joseph R. Anderson's brigade to

assault the Federals north of Mechanicsville above the Old Church Road,

closest to where he expected Jackson to arrive.

|

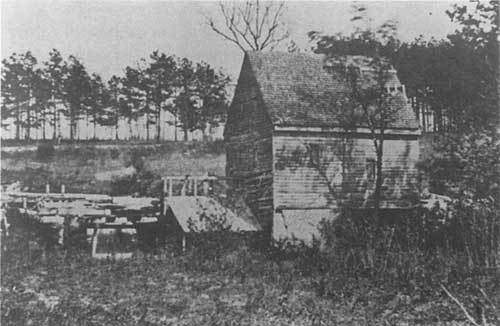

POSTWAR VIEW OF MECHANICSVILLE TURNPIKE BRIDGE, NEARLY HALF OF LEE'S

ARMY CROSSED THE CHICKAHOMINY HERE ON JUNE 26. (NPS)

|

Beaver Dam Creek, a tributary of the Chickahominy flowed almost due

south less than a mile east of Mechanicsville. The Federals had

recognized the great natural strength of the position and built a line

of rifle pits and artillery emplacements on the bluffs above the

eastern bank of the stream. When Hill's men advanced through

Mechanicsville, the defenses of Beaver Dam Creek were manned by the

Pennsylvania Reserves Division, some 8,000 men under the command of

Brigadier General George A. McCall. McCall's men were recent arrivals to

the Peninsula and had gone into position at Beaver Dam Creek just days

before Lee launched his attack.

|

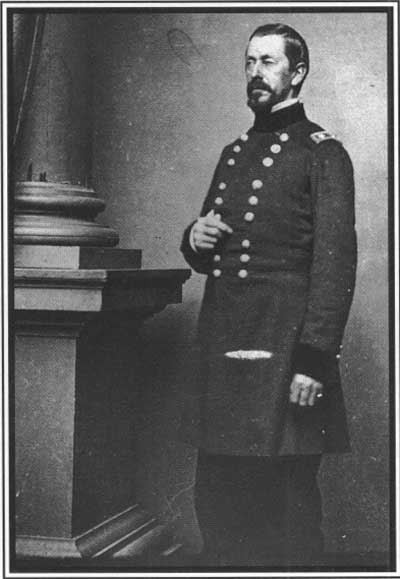

BRIGADIER GENERAL GEORGE A. MCCALL (USAMHI)

|

As Hill's men deployed in lines of battle and went forward, McCall's

artillery opened, dividing its attention between the infantry and a few

Confederate batteries, which were soon silenced with heavy loss. As the

Southern infantry moved down the slope into the stream bottom, McCall's

infantry, ensconced in their rifle pits, prepared for action. A

Pennsylvania private remembered his major encouraging him and his

comrades to "give them hell, or get it ourselves." Hill's men pressed

ever closer, but the Northerners waited. "We did not fire a shot until

they came up within 100 yards of us," wrote Federal private Enos Bloom.

"Then we gave them what the Major told us to give them." Brigadier

General John F. Reynolds rode along his battle line pointing out

targets to his Pennsylvanians: "Look at them, boys, in the swamp there,

they are as thick as flies on a ginger bread; fire low, fire low."

Another of McCall's privates recalled that "the enemy charged bayonets

on us three times, but we cut them down . . . I fired until my gun got

so hot that I could barely hold it in my hands." "We piled them up by

the hundreds," reported Private Bloom, "making a perfect bridge across

the swamp."

Despite such withering fire, enough Confederates made it across the

creek to give the Second Pennsylvania Reserves some anxious moments. "At

one time they charged the left and the centre at the same time,"

recalled one officer, "boldly pressing on their flags until they nearly

met ours, when the fighting became of the most desperate character, the

flags rising and falling as they were surged to and fro by the

contending parties. . . . Our left was driven back, the enemy . . .

bending our line into a convexed circle." These were the men of the 35th

Georgia, whom Anderson had sent toward the extreme Federal flank in the

hope of flanking the Pennsylvanians, but the Georgians failed and were

thrown back with heavy loss.

To the south, Hill pushed more brigades into action at Ellerson's

Mill. To reach the stream, the Confederates had to cross a broad plateau

while Federal artillery across the creek hammered away at them. A

Virginia battery boldly came forward and was smashed, losing 42 of 92

men and many horses. Brigadier General Dorsey Pender's brigade strode

toward the mill and felt the sting of more than a dozen Federal cannon

and supporting infantry. Pender's assault, like those before it, failed

to dent the Federal line. After 6 P.M., Lee found Brigadier General

Roswell Ripley's Brigade in Mechanicsville and, believing the Federals

were vulnerable near Ellerson's Mill, ordered Ripley to attack. The

slaughter was horrible as the Pennsylvanians, secure behind their

breastworks, loaded and fired at the open targets as rapidly as they

could. Ripley's men fell as hay before a scythe. His 44th Georgia alone

lost 324 men—60 percent of the regiment's strength.

|

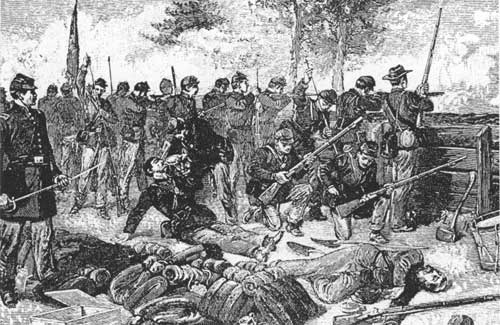

SOME OF THE HOTTEST FIGHTING AT BEAVER DAM CREEK CENTERED AROUND

ELLERSON'S MILL WHERE MASSED FEDERAL ARTILLERY AND ENTRENCHED UNION

INFANTRY REPULSED REPEATED CONFEDERATE CHARGES. (NA)

|

|

FIRING FROM BEHIND WELL-PREPARED EARTHWORKS, MCCLELLAN'S MEN DESTROYED

CONFEDERATE ATTACKERS AT BEAVER DAM CREEK WITH RIFLED WEAPONS THAT HAD A

RANGE OF 500 YARDS. (BL)

|

Darkness closed upon the scene of suffering, ending the combat and

initiating a night of torment for the hundreds of wounded men lying in

the swamp. This first battle of Lee's career with the Army of Northern

Virginia was a stinging defeat, costing him 1,500 men, about 10 percent

of his force engaged, in exchange for fewer than 400 Federals.

Despite the setbacks, delays, and bloody sacrifices of the day, Lee's

plan was working, albeit too slowly and not exactly as had been

intended. Jackson had reached his assigned place at Pole Green Church

late in the day. He was then on the Federal flank above the headwaters

of Beaver Dam Creek, just where Lee wished him to be. Although Hill was

at the same moment making no progress in forcing the Federals from their

works, the Northerners' position was, thanks to Jackson, already

untenable, though Fitz John Porter did not yet know it.

The Federals could not long remain at Beaver Dam Creek with Jackson

on their flank, and as soon as McClellan confirmed Jackson's presence

that night, he ordered Porter to withdraw. McCall's men were angry that

they had to abandon the positions they had successfully defended and

even angrier that McClellan's order came to them just before dawn and

they had to leave so hastily that they could not prepare an adequate

rear guard. The Confederates advanced promptly in the morning and

captured scores of McCall's men attempting to cover the retreat of

Porter's corps.

|

|