|

THE CIVIL WAR'S COMMON SOLDIER

The American Civil War, like all such uprisings, was slow in

conception and subtle in development. Political commissions and

omissions lay at the roots of the explosion. The existence of slavery in

a new nation that proclaimed liberty for all, the role of the previously

sovereign states in a central government yet to be clearly defined, the

growing industrial might of the North competing more and more with the

"Cotton Kingdom" agriculture of the South, a general lack of

understanding and communication between the sections of a country that

was a United States in name only—these were the major issues that

neither time nor statesmen could resolve. So in December 1860, the

shouting turned to shooting, the politician gave way to the soldier, and

war replaced uncertainty.

In a conflict that was the largest in the history of the Western

Hemisphere, the Civil War brought unprecedented suffering in every form.

Yet the greatest tragedy of all was that both sides were fighting for

the same thing: America, as North and South each envisioned what the

still-ripening republic should be.

Young men of the Union and Confederacy alike went to war to defend

the same Constitution. A Louisiana recruit wrote in June 1861 that he

and his friends were Confederate soldiers because "the Magna Carta of

liberties, the constitution," had "fallen entirely into the hands of

[Northern] fanatics." Another Confederate put it succinctly: "We are

fighting for the Constitution that our forefathers made, and not as old

Abe would have it." A few months later, an Ohio private asserted that "the strength of the

nation is to be tried here, whether we have a country or not; whether

our constitution is a rope of sand, that it may be severed wherever it

is smote."

|

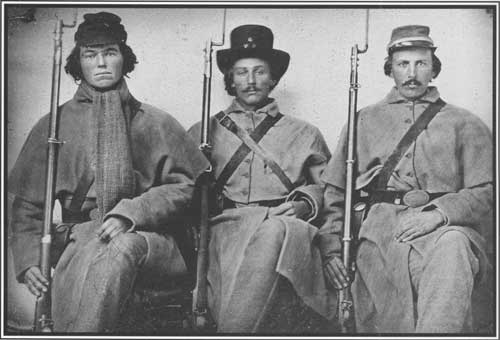

CONFEDERATE SOLDIERS OF COMPANY D, 3RD GEORGIA INFANTRY. (MC)

|

In America's eighth decade, preserving the Union and preserving a

way of life had somehow become incompatible ideals. The most effective

motivation for Northern recruits was "the Union" and all that it

denoted. Many remembered their grandparents relating thrilling stories

of the 1770s and the fight for American independence. Again and again in

the letters of Billy Yanks, one encounters the phrase "fighting to

maintain the best government on earth."

Southerners saw the outbreak of civil war in a different light. A

North Carolinian explained: The Southern States passed ordinances of

secession for the purpose of withdrawing from a partnership in which the

majority were oppressing the minority, and we simply asked "to be let

alone."

|

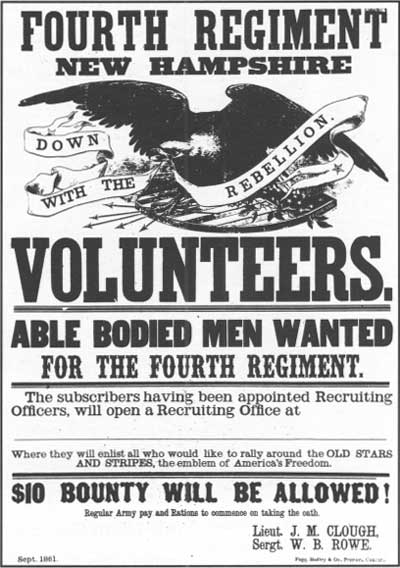

CALL FOR VOLUNTEERS RECRUITING POSTER FROM SEPTEMBER 1861. (LC)

|

Protection of home and hearth also became fundamental aims of both

sides. One Southern enlistee in 1861 explained why he was joining the

army: "If we are conquered we will be driven penniless and dishonored

from the land of our birth.... As I have often said I had rather fall in

this cause than to live to see my country dismantled of its glory and

independence—for of its honor it cannot be deprived."

A Wisconsin private felt essentially the same way two years later.

To his sweetheart he wrote: "Home is sweet and friends are dear, but

what would they all be to let the country go in ruin, and be a slave....

I know that I am doing my duty, and I know that it is my duty to do as I

am now a-doing. If I live to get back, I shall be

proud of the freedom I shall have, and know that I helped to gain that

freedom. If I should not get back, it will do them good that do get

back."

In 1861 tens of thousands of American youths on both sides rushed to

answer the call to arms. They became soldiers because they had been

caught up in the heated atmosphere and angry words of the day, or they

had been emotionally moved by swaying oratory, inspiring music,

patriotic slogans, the sight of a flag waving defiantly in the air.

Youthful innocence and dreamy passion swept them onward. A Confederate

veteran later recalled: "I was a mere boy [in 1861] and carried away by

boyish enthusiasm. I was tormented by a feverish anxiety before I joined

my regiment for fear the fighting would be over before I got into

it."

Those recruits were ready to fight, but few of them knew how to

fight. The War of 1812 was history, the Mexican War a vague childhood

recollection to most of the youths drawn into the struggle of the 1860s.

They had no conception of drill, life in the open, following orders

unhesitatingly, mastering weapons, digging earthworks, and eating

unfamiliar food. They would confront the novelty of living in company

with thousands of strangers. They would face diseases they had never

known and wounds they had never imagined. And through it all, these

common-folk-turned-soldiers would endure homesickness to a degree none of them had ever

envisioned.

|

RECRUITING OFFICE OF NINTH MASSACHUSETTS BATTERY, BOSTON, 1862. (LC)

|

About 3,000,000 soldiers fought in the Civil War, with the North

having a 2 to 1 ratio. The men of blue and gray were far more alike than

unalike. Mostly products of rural backgrounds, they spoke the same

language and shared the same heritage. They had common hopes; they

endured common hardships. The majority of soldiers knew the basic

rudiments of reading and writing. Billy Yanks tended to be better

educated because most Northern states had better school systems. In some

units formed in the rural South, illiteracy was pronounced. Thirty-six

of 72 privates in one North Carolina company made a mark rather than a

signature at the muster-in; 27 of 100 recruits in another Tarheel

company did the same.

Johnny Rebs and Billy Yanks were also highly independent-minded.

They went off to war as citizen-soldiers: volunteers who tended to

remain more citizen than soldier. Very seldom did these men became fully

regimented and militarized. Many of them retained in large measure an

ignorance of army life and an indifference to army discipline. In camp,

on the march, and in battle, they fought with a looseness

that no amount of training could remove. Soldiers on both sides

demonstrated that they could be led but they could not be driven; and

any officer who attempted the latter was bound to encounter at least

resistance and at most rebellion. The individualism of the Civil War's

common soldiers was but a reflection of the societies that spawned

them.

Typical human beings in mid-nineteenth century America, the army

volunteers of North and South performed as one might expect. Many of

them became outstanding soldiers, some of them had rather poor records,

a few were shirkers and cowards; most of them, however, were just

average. Yet for four horrible years those representatives of the

nation's common folk bore on their shoulders the heaviest

responsibilities that have ever been placed on the people of this land.

And they carried that burden so well that we still marvel at their

strength and endurance.

Their story is a mixture of hardship, humor, and heroism—which

are doubtless the ways in which Johnny Rebs and Billy Yanks would like

to be remembered.

On enlistment, a man's physical condition received little attention

from contract surgeons or anyone else in attendance. Then came about two

weeks in which recruits at a rendezvous camp went through the awkward

process of learning the basic rudiments of camp life, drill, and the use

of arms. By the end of that period, the various companies were organized

into regiments.

The clothing and equipment distributed to each recruit might have

seemed bulky to Northern soldiers, who tended to he abundantly supplied

at the outset. Confederate enlistees often had to rely on individual

efforts to clothe and equip themselves. One Virginian wrote with assurance:

"Wisdom is born of experience, and before many campaigns have been

worried through the private soldier, reduced to the minimum, consisted

of one man, one hat, one jacket, one pair pants, one pair draws, one

pair socks, and his baggage was one blanket, one gum-cloth, and one

haversack."

|

CONFEDERATE SOLDIERS STRIPPING FALLEN UNION TROOPS OF CLOTHING. (LC)

|

Regulation uniforms were dark blue for the North and light gray for

the South. However, cloth—like everything else—quickly became

scarce in the embattled Confederacy. The principal source for Southern

soldier apparel soon became captured Union uniforms. Johnny Rebs sought

to alter the color by dying the clothing in a mixture of walnut hulls,

acorns, and lye. This changed the tint to a light tan which Southerners

labeled "butternut."

The introduction to government-issue attire could be a shock.

Federal uniforms came in four basic sizes. A New England recruit saw a

messmate "so tightly buttoned [that] it seemed doubtful if he could draw

another breath." Over in the 10th Rhode Island, a soldier told of a

friend who was less than five feet tall: "His first pair of army drawers reached to his

chin. This be considers very economical, as it saves the necessity of

shirts."

Of course, with some troops no quality of clothing and equipment

could improve their appearance. In 1863 Louisiana soldier Robert Newell

watched 400 Texas Rangers ride into camp. Newell was repulsed at the sight.

"If the Confederacy has no better soldiers than those we are in A bad

roe for stumps, for they looke more like Baboons mounted on gotes than

anything else."

|

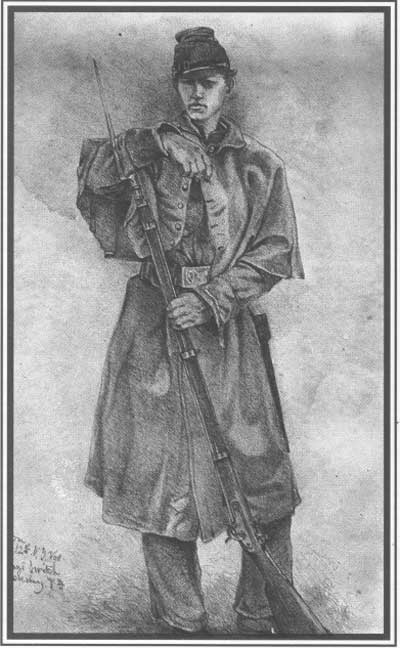

DRAWING BY CIVIL WAR ARTIST EDWIN FORBES OF A SERGEANT MAJOR,

12TH NEW YORK VOLUNTEERS. (LC)

|

Quite often, at the end of basic training, a local delegation (dominated

largely by women) bestowed an ornate flag upon the regiment. The lady

presenting the standard would implore the men in a flowery speech to

love their country and to fight for it with their lives. Accepting

the flag, an officer would respond with an equally glowing address pledging

that his men would never disgrace the sacred banner.

|

SOLDIERS OF THE 23RD PENNSYLVANIA. (USAMHI)

|

On more than one occasion, a foulup made this ceremony ludicrous. Such was

the case the afternoon the women of Fayetteville gave a flag to the 43rd

North Carolina. None of the good ladies was willing to make the

presentation speech, so they invited a local orator of some reputation

to do the honors. The man, a bit nervous at the starring role he was to

have, fortified himself beforehand with a drink, then another, and

another. He managed to stumble to the speaker's stand, and he somehow

got through his address in a halting manner. Then, momentarily

oblivious to everything, he proceeded to give the same speech all over

again—after which he sat down and cried, to the mortification of

the ladies and to the amusement of the soldiers.

|

PRESENTATION OF A REGIMENTAL FLAG ON BEHALF OF THE LADIES OF BOSTON. (LC)

|

Proud recruits who left for war had strong opinions about the

shirkers who remained behind. Private Henry Bear of Illinois gave a

typical expression. From camp in Tennessee, Bear instructed his wife:

"You must tell evry man of Doubtful Loyalty for me, up ther in the

north, that he is meaner than any son of a bitch in hell. I would rather

shoot one of them a great deal more than one [Southerner] living

here."

Unique regiments abounded on both sides during the Civil War. The

1st New York, under Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, was recruited largely from

the New York Fire Department ranks and was known to contain several

dangerous criminals. The average age of all officers and men in the 23rd Pennsylvania was

nineteen. In contrast was the 37th Iowa, known as the "Graybeard

Regiment" because all recruits for this home guard unit had to be at

least forty-five years of age.

Faculty from the Illinois State Normal College so dominated the 33rd

Illinois that it was known as the "Teacher's Regiment." Its officers

were often accused of refusing to obey any order that was not absolutely

correct in grammar and syntax. The "Iowa Temperance Regiment" gained its

sobriquet because its entire membership vowed that it would "touch not,

taste not, handle not spirituous or malt liquor, wine or cider." Some of

the Iowans later in the war violated the pledge, but they were excused

on the grounds that "it has only been at such times as they were under

the overruling power of military necessity."

Civil War armies were young in composition. Ages ranged from lads

with smooth faces to old men with gray beards. The largest single age

group was eighteen, followed by soldiers twenty-one and nineteen.

Unknown numbers of children served in the armies. Edward Black was nine

years old when he entered an Indiana regiment. Among the youngest

Confederate soldiers was Charles C. Hay, who joined an Alabama regiment

at the age of eleven. John Mather Sloan of Texas lost a leg in battle at

the age of thirteen.

The most famous of the dozens of young drummer boys was Johnny Clem

of Newark, Ohio. He went to war at the age of ten. In Clem's first

battle, a shell fragment ripped his drum apart. He became known as

"Johnny Shiloh." Gallantry in action two years later brought him

promotion to sergeant. Clem made the army a

career, and he retired in 1916 with the rank of major general.

|

JOHNNY CLEM, "THE DRUMMER BOY OF CHICKAMAUGA." (USAMHI)

|

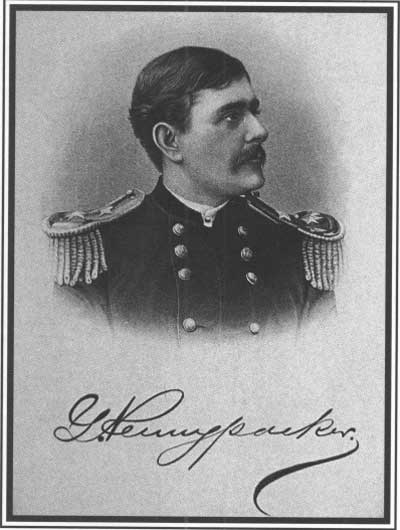

Three "boys" had extraordinary careers in the Civil War.

Pennsylvania's Galusha Pennypacker received promotion to brigadier

general a month before his twenty-first birthday. William P. Roberts

became the Confederacy's youngest general at the age of twenty-three.

Arthur MacArthur, father of the famed World War II commander, won the

Congressional Medal of Honor at Missionary Ridge, Tennessee, while only

eighteen. Months later, MacArthur became colonel of the 24th Wisconsin,

and after the war he rose to lieutenant general in the army.

|

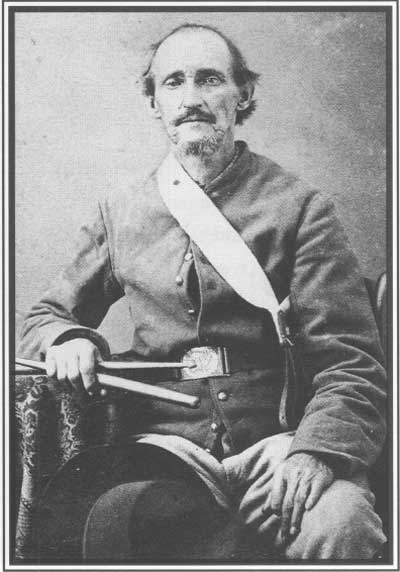

BRIGADIER GENERAL GALUSHA PENNYPACKER (CWL)

|

At the other end of the age spectrum was Curtis King, who served

four months in the 37th Iowa before being discharged for

disability. King was eighty. One of the oldest of the Confederates

was F. Pollard. In the summer of 1862, the 73-year-old North Carolinian

enlisted as a substitute. Pollard was shortly discharged "for

rheumatism and old age."

|

BRIGADIER GENERAL WILLIAM P. ROBERTS (LC)

|

Civil War soldiers came in every size. The shortest service man was

from Ohio and stood 3 feet, 4 inches tall. In contrast, David Van

Buskirk of Indiana was 6 feet, 11 inches in height. Van Buskirk had a

ready reply for those who gawked openly at his stature. When he left for

war, he would say, each of his six sisters "leaned down and kissed me on

top of the head."

Occupations of the soldiers were not as varied as would exist in a

troop call-up today. A survey of 9,000 Civil War soldier occupations

contained 5,600 farmers. The next vocations were students (474),

laborers (472), and clerks (321). Some of the remaining occupations

given were unique. One man termed himself a rogue, another listed his

status as convict, and several recruits put down their occupation as

"gentleman."

The greatest flood of immigration in the nation's history occurred in

the decades just before the Civil War. New England and the Midwest

became home for the vast majority of those new citizens. As a result,

one of every five Billy Yanks was foreign-born. In contrast, one of

every twenty Johnny Rebs was born outside the country. Every nationality

had representatives in the Civil War.

|

JAMES WARD, MUSICIAN, 76TH OHIO, ENLISTED

OCTOBER 9, 1861, AGED SIXTY. (PHOTO COURTESY OF DENNIS KEESEE)

|

|

WILLIAM BLACK, AGE TWELVE, IS CONSIDERED THE YOUNGEST WOUNDED SOLDIER OF THE WAR.

(LC)

|

No foreign group on either side in the war gained greater

renown—positively as well as negatively—than the Irish. They

quickly earned a reputation for overindulgence in whiskey and an

overfondness for fighting, whether it be the enemy or themselves. To

an Indiana soldier stationed near Vicksburg in 1863, the arrival

of some reinforcements was hardly reassuring. "The 90th Ill., the

Irish Regiment," he wrote in his diary, "came into camp just back of us

this morning. And such a time as those fellows did have. They got into a row about putting up their tents and

had a free for all fight and were knocking each other over the head with

pick handles, tent poles, and any thing they got hold of. Pretty soon

their Colonel, O Marah, came out of his tent with a great wide bladed

broadsword that is said to have belonged to some of his ancestors. And the way he did

bast those Irish fellows with the flat of it was a caution. He stopped

the row, and they settled down. His Regiment adore him."

Felix Brannigan of the 75th New York offered a personal explanation

of how he and his fellow Irishmen thought. "As we rush on with the tide

of battle, severe sense of fear is swallowed up in the wild joy we feel

thrilling thro every fibre of our system. . . . There is an elasticity

in the Irish temperament which enables its possessor to boldly stare

Fate in the face, and laugh at all the reverses of fortune . . .

and crack a joke with as much glee in the heat of battle as in the

social circle by the winter fire."

|

ENLISTED IRISH AND GERMAN IMMIGRANTS

IN NEW YORK. WOOD ENGRAVING FROM LONDON ILLUSTRATED NEWS, 1864. (LC)

|

Germans, Italians, English and Canadians also served in large

numbers with the Union armies. Union encampments often sounded

like "a babel of tongues."

|

Germans, Italians, Englishmen, and Canadians also served in large

numbers with the Union armies. Union encampments often sounded like "a

babel of tongues." A Mississippi surgeon once listened to a long line

of Union prisoners pass. He then turned to a colleague and said

despairingly: "Pierce, we are fighting the world."

Representatives of fifteen different countries served in one New

York regiment. Fortunate it was that the Hungarian colonel of the unit

could give orders in seven different tongues. Scandinavians were especially

visible in units from the upper Midwest. The 15th Wisconsin was

predominantly Norwegian. Identity in the unit must have been a problem

for 128 men had the first name of Ole and in one company were five

men named Ole Olsen.

|

|