|

|

THE HOME FIRES

by William Marvel

The Civil War was waged not only on the battlefields and in the

camps, but well behind the lines. From the New England farmer who hired

a boy in place of his soldier son, to the Piedmont housewife who roasted

chicory root as a substitute for her family's coffee, American civilians

could not ignore the conflict.

The South obviously bore the brunt of civilian sacrifice and

suffering. Even by the final months of 1861, before Federal armies had

struck deeply into Confederate territory, the naval blockade had begun

to whittle away at the Southern standard of living. Culinary delicacies

and creature comforts quickly became scarce (and thus more expensive)

for a society that had long imported most of its goods. As the war

progressed, drugs and other medical supplies disappeared. Salt, which

proved so essential to food preservation and the curing of animal hides,

became the fore most commodity on the black market. Field armies

absorbed all that Confederate industry could produce. A higher

proportion of Southern farmers died or came home disabled than their

Northern counterparts, and a greater percentage were taken for the army;

as the remaining growers turned to speculation in cotton and other cash

crops, shortages developed even among the staple foods that the agrarian

South had traditionally provided for itself.

While an early lack of fine wines or dress silk afflicted only the

upper classes, the resulting increase of prices struck more painfully

with each step down the social ladder. Poorer Southerners suffered more,

however, from the plummeting value of Confederate paper currency.

Inflation spiraled in triple digits through most of the war, and by the

middle of the conflict the Confederate capital was the scene of a bread

riot. Decline in the production of food, a dearth of salt, and the

destruction of stores and transportation by the Union armies brought

some regions to the brink of famine by the end of 1864, dragging

thousands of deserters out of the fight and shattering the will of many

Southerners to continue the struggle.

|

A WOODCUT DEPICTING THE DISTRIBUTION OF RATIONS. (LC)

|

Nearly every Northern community escaped outright want. Money, and to

some extent manpower, composed the principal difficulties for civilians

in the loyal states. Government contracts increased job opportunities

but did not always improve the worker's economic situation. Often,

wartime production meant longer hours and lower pay: even as carpenters

at the Portsmouth naval shipyard finished the sloop that would sink the

Confederate cruiser Alabama, the commandant announced that the

workday would begin thereafter at sunrise, and wages would be cut by as

much as one-quarter.

Although inflation posed a less serious problem for U.S. citizens

than it did in the Confederacy, it still ate away at the workingman's

ability to support himself, and the introduction of large numbers of

women into the unskilled work force helped to diminish the labor demands

that might have swelled wages enough to offset the shrinking value of

greenbacks. Industry did lose a substantial ratio of its skilled workers

to the army and navy, but New England agriculture probably felt the

greatest labor shortage. For two decades New England farm families had

been losing their sons to manufacturing or to the more fertile soil of

the plains; geography did not adapt the rocky Yankee hill farms to the

mechanical implements that supplemented scarce labor north of the Ohio,

and the sudden exodus of thousands of prime farm hands forced many New

Englanders to reduce crops drastically. Many such farms never resumed

their former production, and the war at least accelerated the decline of

agriculture in the Northeast.

Rich or poor, the male Northern citizen preoccupied himself at one

time or another with the possibility that he might be drafted, but most

never saw an armed rebel or endured any fear of enemy depredations

against himself or his property. Even during the great raids into

Maryland and Pennsylvania, Confederates did not pillage the countryside,

taking only horses and provisions with little wanton destruction,

whereas Southerners whose homes lay in the path of Union armies

frequently lost everything they owned and occasionally suffered personal

violence as well. The difference lay in the military philosophies of the

contending sides. Southern forces operated largely to defeat or

discourage the Union armies, after the genteel European fashion; Federal

generals like William Sherman eventually realized that the swiftest path

to victory was to destroy the very fabric of Southern society, striking

simultaneously at the Confederacy's military might and civilian

morale.

|

|

ILLUSTRATION FROM HARPER'S WEEKLY TITLED "THE STAG DANCE,"

SOLDIERS OFTEN MADE UP AMUSEMENTS TO ALLEVIATE THE TEDIUM OF CAMP LIFE.

(LC)

|

|

A HUMOROUS "BRAWL" BREAKS OUT AT UNION CAMP. (LC)

|

Nostalgia is always the great enemy of soldier morale. This was

especially true of the men of blue and gray, most of whom were away from

home for the first time. Moreover, these were young men looking for

excitement and susceptible to temptations. As a Virginian told his

cousin: "I have not seen a gal in so long a time that I would not know

what to do with myself if I were to meet up with one, though I recon I

would learn before I left her."

Prostitution thrived during the war years. From a Kentucky encampment

in the spring of 1864, an Indiana soldier wrote his family in disgust:

"The godlessness [of this area] is great, cursing and whoring cries to

heavn. Men from our company, yes even married ones, have gone to whore

houses and paid 5 and 6 dollars per night. I was astonished. If their

wives would know about it, it would cause terrific fights and maybe

divorce. That's why I don't want to name them."

In 1863, more than 7,000 prostitutes were working in Washington, D.C.

Some of the bordellos in the Northern capital had such stimulating names

as "The Haystack," "Hooker's Headquarters," and "Madame Russell's Bake

Oven." Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederacy, was hardly

any better. One madam there opened a bawdy house immediately across the

street from a soldier hospital. Shortly thereafter, the hospital

superintendent complained angrily that the prognosis of many of his

patients had taken sharp turns for the worse. Prostitutes, he explained,

were appearing at their windows in various stages of nudity, and they

were making highly provocative gestures. As a result, patients were

sneaking and hobbling from the hospital with little thought to the

seriousness of their condition.

|

HEADQUARTERS OF HOOD'S TEXAS BRIGADE IN VIRGINIA. (MC)

|

|

SEVERAL GENERATIONS OF A SOUTHERN FAMILY. (SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DEPT.

EMORY UNIVERSITY)

|

More often than not, soldiers North and South displayed the rude

strength of youth by exhibiting a terrible capacity for loneliness. Two

months into the war, Captain Harley Wayne of an Illinois regiment wrote

his wife that many of his lads were grieving with homesickness. "I found

one crying this morning," Wayne reported. "I tried to comfort him but

had hard work to keep from joining him."

Accentuating that loneliness was a sentimentality deep and

characteristic of the 1860s. The Civil War brought those two emotions

together and created a deep love alien to most modern generations caught

in the whirlpool of life in the late twentieth century. Romance was an

overpowering sentiment among the men of blue and gray.

Once in the army, acquiring a sweetheart became a triumph just short

of victory in battle. Illinois soldier John Shank wrote home about his

new girlfriend: "I intend to have her for my wedded wife if I ever get

home safe again. She is about 16 years old. She has black eyes and dark

hair and fair skin and plenty of land and that aint all." Another Billy

Yank was more specific about his new love. "My girl is none of your one

horse girls," he announced. "She is a regular stub and twister. She is

well-educated and refined, all wildcat and fur, and Union from the

muzzle to the crupper."

Soldiers and the folks back home generally maintained the most

regular correspondence possible. Georgia soldier William Stillwell was a

great tease; he enjoyed bantering with the home folk, and one suspects

that he did so in great part to bolster the morale of all concerned.

Stillwell had not seen his wife for a year when he informed her in

matter-of-fact terms: "If I did not write and receive letters from you I

believe that I would forgit that I was marrid. I dont feel much like a

maryed man but I never forgit it so far as to court enny other lady, but

if I should you must forgive me as I am so forgitful."

|

A MEMBER OF THE OHIO VOLUNTEER INFANTRY AND HIS WIFE. (COURTESY OF

DENNIS KEESEE)

|

Husbands and wives were not as forthright and uninhibited in their

letters as one might expect. Civil War generations wrote in guarded

fashion. Rarely did that reserve break down. One instance occurred in

April 1864, when a young Southern wife wrote her soldier-husband: "My

loving John, I feel like I would squeese you and hug you to death if I

had a chance. You would not sleep in a week if I got my arms around you.

I will make up for lost time [when you come home], so you hold yourself

in readiness."

More often than not, soldiers and wives devoted much space in their

letters to an attempt to combat mutual loneliness. Indiana volunteer

John Craft had never been away from home before joining the Federal

army. Shortly after Christmas 1861, when his wife seemed unable to

control her depression, Craft wrote back: "Eliza you must not be

discouraged. Remember the Sun is never brighter than when it emerges

from behind the darkest cloud. ... I have abiding faith that all will be

well yet; that our government will be sustained; that we will have yet a

country, a Home, and time and opportunity alloted us to enjoy them."

The ultimate test of a soldier is battle. All else in warfare is

incidental to two armies closing in combat. Northern and Southern troops

may have left a good deal to be desired in camp and on the march, yet

they more than compensated for those deficiencies by their overall

performance on the battlefield. Sir Winston Churchill once said of Civil

War soldiers: "With them, uncommon valor became a common virtue."

Letters and diaries of those men reveal that the most prevalent fear

they had was not the possibility of being wounded, or even killed, but

of "showing the white feather": of displaying cowardice that would bring

humiliation to family and friends back home. A large percentage of

soldiers hoped for a battle wound ("a red badge of courage"), but

uncertainty gripped all of them as they moved toward their first battle.

Differing reactions occurred before hell literally broke loose. Soldiers

remembered sweatiness, nervousness, praying fervently, "a violent

pounding in the heart," "shaking hands with everyone around you,"

"losing control of bowels," and "urinating in pants."

|

MEMBERS OF A UNION ARMY TRANSPORT PHOTOGRAPHED OUTSIDE THEIR CAMP. (LC)

|

Teenager Edward Edes of the 33rd Massachusetts wrote on the eve of

his baptism in combat: "I have a mortal dread of the battlefield . . . I

am afraid that the groans of the wounded & dying will make me shake,

nevertheless I hope & trust that strength will be given me to stand

up & do my duty." Edes performed admirably in his first battle but

died of sickness a year later.

In marked contrast to Currier and Ives paintings and other orderly

depictions of the Civil War, the actual fighting was not clean or visual

at all. An assault tended to be an interrupted, accordion-like advance

across a field with fixed bayonets. The attacking soldiers would rush

forward a few yards, fire a volley, reload, dash several more yards,

fire again, and then make a final run toward the enemy works. No matter

how precise or meticulous the charge was designed to be, the whole

situation tended to disintegrate the moment the battle began.

|

A CURRIER AND IVES PRINT OF THE BATTLE AT CEDAR MOUNTAIN. (LC)

|

Feelings on going into combat were mixed. A Mississippian wrote of

his initial battle action: "This was my first experience at being shot

at, and I was as scared as the next man." One New York soldier who was

part of an assault described his feelings to his sweetheart: "When we

first started from our position, I thought of home, friends, and most

everything else, but as soon as we entered the woods where the shells

and balls were flying thick and fast, I lost all fear and thought of

home and friends, and a reckless don't-care disposition seemed to take

possession of me."

Men who had come from farms, factories, schools, and stores

unanimously admitted that fighting was the hardest task they had ever

performed. No time existed in battle for rest; food and water were

practically nonexistent in the struggle. Anxiety, nervous energy, and

exuberance all took such a toll that by midafternoon many soldiers were

barely able to stand, much less to load and fire a gun.

|

DEAD SOLDIERS ALONG THE SUNKEN ROAD AT ANTIETAM. (LC)

|

No participant in the Civil War ever forgot a battle scene. It so

exceeded anything they had ever witnessed that soldiers had difficulty

composing word-pictures of it. Still, a Billy Yank came close to

unloading all of his impressions with this account of the fighting at

Gettysburg: "Foot to foot, body to body and man to man, they struggled,

pushed and strived and killed. Each had rather die than yield. The mass

of wounded and heaps of dead entangled the feet of the contestants, and,

underneath the trampling mass, wounded men who could no longer stand,

struggled, fought, shouted and killed—hatless, coatless, drowned in

sweat, black with powder, red with blood, stifling in the horrid heat,

parched with smoke and blind with dust, with fiendish yells and strange

oaths they blindly plied the work of slaughter."

Chaos reigned everywhere. Thick, acrid smoke settled over the arena;

and in the crash of musketry, the explosion of artillery fire, the

screams of men fighting and dying, a soldier at best saw only what was

directly in front of him. Officer casualties were high because it was

customary for company, regimental, and brigade commanders to lead their

men into action. Once thousands of troops became engaged in frenzied

fighting, any firm control was impossible. The common soldiers were left

to their own to wage the contest. Their courage and tenacity, both

individually and collectively, often decided the outcome of the

engagement.

In every army are men who can stand some things but not everything:

soldiers whose feelings for survival override devotion to duty. When

cowardice occurred in the Civil War, the steadfast ones viewed it with

utter contempt. Sergeant Harold White of the 11th Iowa recalled at the

battle of Shiloh that a frightened fugitive shouted as the Iowans moved

into action: "Give them hell, boys! I gave them hell as long as I

could!"

White observed: "Whether he had really given them any, I cannot say,

but assuredly he gave them everything else he possessed, including his

gun, cartridge box, and hat."

For every soldier who lacked fortitude in the Civil War, 100 others

were quick to rise to the heights of courage. A call for volunteers for

a dangerous task would bring shouts of response. When charging against

concentrated musketry, Civil War soldiers were known to lean forward as

if they were advancing into the face of a heavy rainstorm. Men jumped

atop parapets to yell defiance at the enemy; they begged for the

privilege of carrying the regimental colors; they took command without

being told when all of the officers were disabled; they refused to leave

the field when seriously wounded; many cheered on their comrades with

their final dying breath.

|

JOHN WALTON ENLISTED IN AUGUST 1862 AT AGE TWENTY WITH THE 95TH OHIO

VOLUNTEER INFANTRY. HE WAS CAPTURED IN JUNE 1864 AND HELD PRISONER.

(COURTESY OP DENNIS KEESEE)

|

Soldiers North and South came to have a mutual respect for the

courage and sacrifice of their opponents. After the battle of Shiloh a

Midwestern cannoneer praised the Confederates to a friend: "If we ever

had a notion in our heads that those fellows couldn't shoot, it was

dispelled." Another Billy Yank was even more laudatory of the

Southerners in that contest. "Never did I see such men fight. When you

heare . . . a man say they wont fight tell him he nows nothing bout them

for wen our cannons would mow them down by hundreds others would follow

and take their plase and fight like demons."

When a shell tore off both hands of a Confederate soldier, the man

stared at his two bleeding stumps and mumbled: "My Lord, that stops my

fighting." Major James Waddell stated in his official report of the

battle of Second Manassas that his Georgia regiment "carried into the

fight over 100 men who were barefoot, many of whom left bloody

foot-prints among the thorns and briars through which they rushed with

Spartan courage and jubilant impetuosity, upon the ranks of the foe."

Before one of the bloodiest assaults of the war, Union soldiers were so

convinced of the futility of their assignment that they wrote their

names and units on pieces of paper and pinned them to their shirts so

that the burial details could make easier identification. One New

Englander hastily wrote in his diary: "June 3, 1864, Cold Harbor. I was

killed." The journal was found in the coat pocket of the dead

soldier.

|

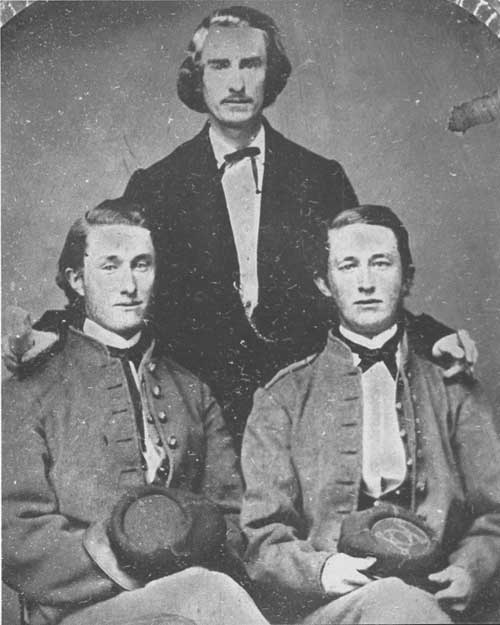

THE WARREN BROTHERS: LEVIN AND LUTHER (L-R) SERVED IN THE 19TH

BATTALION, VIRGINIA HEAVY ARTILLERY. THEY ARE SHOWN WITH THEIR FATHER,

PATRICK. (MC)

|

With the end of a battle, the surviving participants soon felt a

bone-deep weariness. Scores of them would begin searching the field,

nearby hospital stations, and camp for a comrade who was missing. Only

rarely would he be found. Soon after darkness fell, the soldiers would

sink to the ground somewhere and, in spite of the screams and moans

coming from the nearby battleground, sink into a fitful sleep of

exhaustion.

The aftershock of battle could be traumatizing for the survivors. A

soldier from Maine tried to tell his parents what part of one battle

arena contained: "I have Seen . . men rolling in their own blood, Some

Shot in one place, Some another. . . . our dead lay in the road and the

Rebels in their hast to leave dragged both their baggage wagons and

artillery over them and they lay mangled and torn to pieces so that Even

friends could not tell them. You can form no idea of a battle field . .

. no pen can describe it. No tongue can tell its horror." Another

soldier noted: "When the fight was over & I saw what was done, the

tears then came free. To think of civilized people killing one another

like beasts. One would think that the supreme ruler would put a stop to

it."

Sometimes the soldiers did precisely that on a momentary basis.

During the war an amazing degree of fraternization took place between

men of opposing armies. Pickets often shared conversation, newspapers,

tobacco, coffee, even letters from home; unauthorized truces occurred

more than once because of a blackberry patch or a swimming hole

discovered in the no-man's land between opposing lines.

Many soldiers found it unnatural during the long periods of

inactivity to shoot at an enemy who had become an acquaintance. At one

point in the long siege of Petersburg, Virginia, Private George W.

Buffum of Wisconsin told his wife: "We dont shute at woune a nother

unles we let woune another no before we commenc fiering. We hay orders

to fier wounc in a while to ceep the pickitts in snug, than we howler

take care boys we are going to fier and then we lay to until we git

threw."

|

|