|

|

THE ROLE OF BLACK SOLDIERS

by James I. Robertson, Jr.

Just as the black man played a central part in causing the Civil War,

so did he play a major role in determining its outcome.

An Illinois soldier wrote of sentiments in 1861: "If the Negro was

thought of at all, it was only as the firebrand that had caused the

conflagration—the accursed that had created enmity and bitterness

between the two sections, and excited the fratricidal strife." Quite in

contrast was the observation of Pennsylvania soldier Oliver Norton.

Writing from Virginia in January, 1862, Norton stated: "I thought I

hated slavery as much as possible before I came here, but here, where I

can see some of its workings, I am more than ever convinced of the

cruelty and inhumanity of the system. It has not one redeeming

feature."

The idea among Union officials of using former slaves as soldiers

evolved slowly. It developed through stepping stones of hostility,

discrimination, and tragedy. Federal authorities had little objection to employing

blacks as army laborers, but Northern sentiment was widespread that arming

blacks would be degrading for the country. Others feared that

mobilization would invite insurrection. Many Northeners agreed with

Southern slave-holders: blacks were inferior beings incapable of

fighting with the intensity and courage of white men.

Abolitionists, patriots, and humanitarians saw compelling reasons

for placing blacks in uniform. Their numbers would add tremendous

strength to Federal forces; their presence would give new meaning to the

concept of American democracy; military service, from the blacks' point

of view, would prepare and justify them for full admission into postwar

society.

When Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on

January 1, 1863, it opened the door for the formal recruitment of black

soldiers. Progress was slow because of reluctance on the part of large

numbers of Union officials. Not until high-ranking Federal commanders

underwent a change of attitude did the program gain momentum.

For example, in the summer of 1863, General U.S. Grant had seen enough

to write Lincoln: "By arming the negro we have added a powerful ally. They will make good

soldiers and taking them from the enemy weakens him in the same

proportion they strengthen us. I am therefore most decidedly in favor of

pushing this policy."

The most important factor in the final acceptance of blacks as

soldiers was their performance in battle. No amount of talk or

propaganda could have won the black soldier a rightful place in the

Union army. He had to achieve that place himself, soldier-fashion, in

bloody combat. This they did, and proudly.

|

ATTACK ON FORT WAGNER BY THE 54TH MASSACHUSETTS, THE FIRST

BLACK REGIMENT FROM THE NORTH TO GO TO WAR. (LC)

|

In the last half of the Civil War, black troops fought in 41 major

battles and scores of minor engagements. At Fort Hudson, La., on May

27, 1863, blacks made their first formal assault of the war. Some 1,080

of them were part of an attack against a 6,000-man Confederate garrison.

The blacks did not flinch but literally threw themselves against the

enemy works. Over 300 blacks were listed among the casualties of the

unsuccessful assault. Ten days later, at Milliken's

Bend, La., the tables were reversed. Southerners assailed a position

manned by black soldiers. Some of the most vicious fighting of the war

ensued as the blacks held their lines.

Glory came to black soldiers the following month at Fort Wagner,

S.C. Close to 5,000 Federals charged across a wide expanse of open

beach against a strongly fortified position. In the forefront of the

attack was the 54th Massachusetts, the first black regiment from the

North to go to war. This unit had been struggling through tangled

marshland for two days, in pouring rain and without food. Yet it surged

forward heroically at Fort Wagner; in the illfated attack the blacks

lost 100 killed, 145 wounded, and 100 captured. The Atlantic

Monthly later declared: "Through the cannon smoke of that dark

night, the manhood of the colored race shines before many eyes that

would not see."

Throughout the Civil War, black soldiers had to weather a host of

discriminations. The Confederacy initially refused to grant them the

rights and privileges accorded to white Billy Yanks seized in battle.

For most of their Civil War service, blacks received only half the pay

of whites. They served in completely segregated regiments and, with rare

exceptions, were led by white officers. The worst duties in camp and

field customarily went to black commands. Their uniforms and equipment

as often as not were discards and rejects.

Constant harassment from white Billy Yanks further hampered the

efforts of the blacks to attain recognition. In the summer of 1861, an

Indiana lieutenant wrote his sister: "I do not believe it right to make

soldiers of them and class & rank them with our white soldiers.... I

do despise them, and the more I see of them, the more I am against the

whole black race." A New York soldier once made the terse comment: "I

think the best way to settle the question of what to do with the darkies

would be to shoot them."

|

BLACK TROOPS LIBERATE SLAVES IN NORTH CAROLINA. WOODCUT FROM

HARPER'S WEEKLY, JANUARY 1864. (LC)

|

Many of those feelings never ameliorated, but the majority of them

did. After the bloody 1864 battle of Nashville, Union General George

H. Thomas looked at the battlefield strewn with bodies and exclaimed:

"Gentlemen, the question is settled. Negroes will fight."

A total of about 179,000 blacks served as soldiers in the Civil War

and later on the western frontier. They were organized into 120 infantry

regiments, 22 artillery batteries, and 7 cavalry regiments.

Cumulative losses in black units in the 1860s and 1870s were unusually

high: 68,200—more than a third of the total enrolled. Of that

number, 2,750 were killed in action; the remaining 65,450 perished from

wounds and sickness. The number of desertions among black troops was

about 7% of the total in the army. Twenty-one blacks received the

Congressional Medal of Honor for gallantry in action.

In 1892, Colonel Norwood P. Hall of the 55th Massachusetts (Colored) Regiment proudly

stated of his men: "We called upon them in the day of our trial, when

volunteering had ceased, when the draft was a partial failure, and the

bounty system a senseless extravagance. They were ineligible for

promotion, they were not to be treated as prisoners of war. Nothing was

definite except that they could be shot or hanged as soldiers. Fortunate

it is for [the nation], as well as for them, that they were equal to the

crisis; that the grand historic moment which comes to a race only once

in many centuries came to them, and that they recognized it ..."

|

The pronounced individualism of American generations during that era

explains in great part the disrespect for authority so commonplace in

the armies. Southerners and Northerners who answered the call to arms

were products of a new nation dedicated to the ideal that one man was as

good as another; and when many of the officers showed themselves to be

at least as inexperienced as the men they were supposed to be leading,

soldiers in the ranks reacted in disgust.

These were civilian armies, formed hastily by the first fires of

war. Most of the men in a company had been lifelong acquaintances.

Before entering the army, they had addressed one another as John, Tom,

or Harry; but once in military service, several of their friends became

their superior officers. Men who had never so much as doffed their hats

at one another now found themselves obligated to salute each other and

to obey orders without question. Relinquishing friendly informality for

stuffy formality taxed the tempers of more than one private.

A North Carolinian pointedly explained the situation in his company:

"The rank and file of the Anson Guards

were the equals, and superiors to some of their officers; socially, in

wealth, in position and in education, and it was a hard lesson to learn

respectful obedience." In other words, the average soldier was willing

to obey all orders that were sensible, provided the man giving them did

not get too puffed up about it.

Verbal attacks on officers were frequent and involved the use of

such references as "whorehouse pimp," "a vain, stuck-up, illiterate

ass," "a whining methodist class leader," and one of the most classic

of all time: "a God damned fussy old pisspot." Yet the phrase that got the most

men hauled before a military court was the time-honored "son of a bitch."

|

AN UNIDENTIFIED OFFICER (LEFT) POSES WITH AN ENLISTED MAN

(COURTESY OF DENNIS KEESEE)

|

|

PICTURED L-R: UNIDENTIFIED CAPTAIN'S COOK, CAPTAIN LOUIS HILLEBRAND, AND

1ST SERGEANT W. R. PEDDLE OF THE 23RD PENNSYLVANIA.(USAMHI)

|

A Southerner once classified his colonel as "an ignoramus fit for

nothing higher than the cultivation of corn." One soldier from Florida

was convinced that all officers were "not fit to tote guts to a bear.""

Billy Yanks shared such feelings. "The officers," one Massachusetts

soldier asserted, "consider themselves as made of a different material

from the low fellows in the ranks....They get all the glory and most of

the pay and don't earn ten cents apiece on the dollar the drunken

rascals."

When a thoroughly disliked general succumbed to illness early in

1865, one of his men wrote home: "Old Landers is ded. . . I did not see

a tear shed but heard a great many speaches made about him such as he

was in hell pumping thunder at 3 cents a clap." Yet the choicest

denunciation of all came from an Illinois private who once intoned: "I

wish to God one half of our officers were knocked in the head by

slinging them Against A part of those still Left."

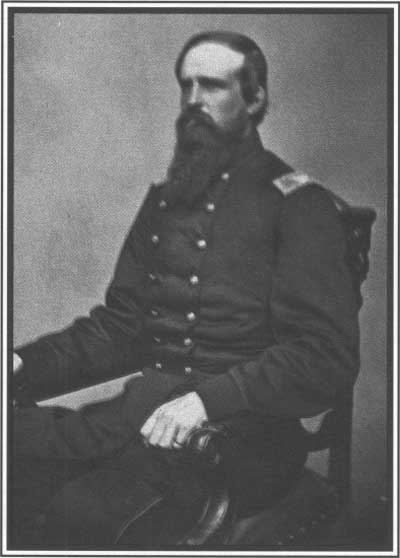

In contrast, those officers who led with gentle persuasiveness and

possessed real understanding about their men almost without exception

received obedience and respect. When widely esteemed Colonel Edward E.

Cross of the 5th New Hampshire fell mortally wounded at Gettysburg, his

last words were: "I think the boys will miss mess." They did; the

regiment was never quite the same after Cross's death.

|

COLONEL EDWARD CROSS (CWL)

|

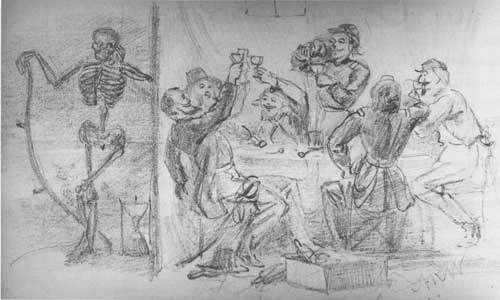

Alcohol consumption triggered the most continual misbehavior in

Civil War camps. The men drank for several reasons

and usually to excess. A Louisianian stated of a compatriot: "I never

knew before that Clarence was so much addicted to drinking. If he had

been as fond of his mother's milk, as he is of whiskey, he would have

been awful hard to wean."

|

"HERE'S A HEALTH TO THE NEXT ONE THAT DIES." SKETCH BY

ALFRED WAUD.

|

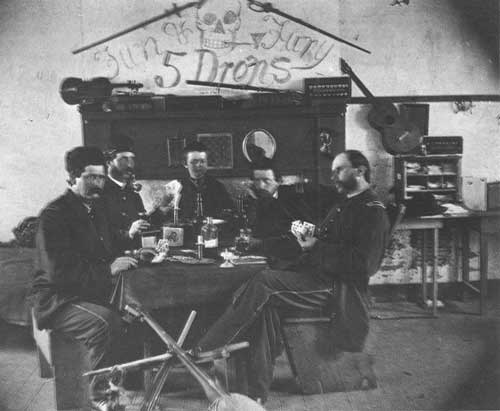

Most of the whiskey brought or smuggled into the armies could be

classified as "mean" even for that day. A Hoosier soldier analyzed one

issue of whiskey and with a straight face adjudged it to be a

combination of "bark juice, tar-water, turpentine, brown sugar,

lamp-oil and alcohol." The potency of the liquor is readily evident

from some of the nicknames given to it: "Old Red Eye," "Rifle

Knock-Knee," "How Come You So," and "Help Me to Sleep, Mother."

The liquid surely produced some startling reactions, especially among

commanders. One night in the spring of 1861, Confederate General Arnold

Elzey and his staff engaged in a long and boisterous party. Whiskey

flowed copiously. At one point, a fairly inebriated Elzey called in the

sentry guarding his tent and kindly gave the man a drink. The revelry

eventually ran its course; Elzey collapsed in bed and fell into a deep

sleep. About dawn, he was aroused by the sentinel, who exclaimed:

"General! General! Ain't it about time for us to take another

drink?"

|

UNION SOLDIERS PICTURED PLAYING CARDS

AND DRINKING "OLD RED EYE." (LC)

|

In February 1864, the officers of the 126th Ohio had a farewell

party for their colonel. A bucket each of egg nog and bourbon came into

play. The result, according to a disgusted bystander, "was a big drunk,

and such a weaving, spewing, sick set of men I have not seen for many a

day... Col. Harlan was dead drunk. One Capt. who is a

Presbyterian elder at home was not much better."

The 48th New York, commanded by the Reverend James M. Perry,

was such a model of good behavior that the regiment became known as

"Perry's Saints." However, while the men were stationed at Tybee Island,

Georgia, in 1862, a large cargo of beer and wine washed ashore after a

storm. The New Yorkers proceeded to get wildly intoxicated. This spree

may have been a leading factor in Colonel Perry suffering a fatal heart

attack at his desk the following day.

On another occasion, an inebriated Union corps commander walked

straight into a tree in front of his tent, then had to be restrained

from arresting the officer of the guard on charges of felonious

assault.

|

"DRUNKEN SOLDIERS TIED UP FOR FIGHTING AND OTHER UNRULY CONDUCT."

DRAWING BY ALFRED WAUD. (LC)

|

Army punishments were imperative for the survival of discipline. Yet

the leading characteristics of Civil War punishments were inequity and

capriciousness. The frequency and degree of army sentences depended in

large measure on the whims of the commanding officer. Sometimes the most

serious offenses were all but ignored, while on other occasions trifling

offenses resulted in severe punishments.

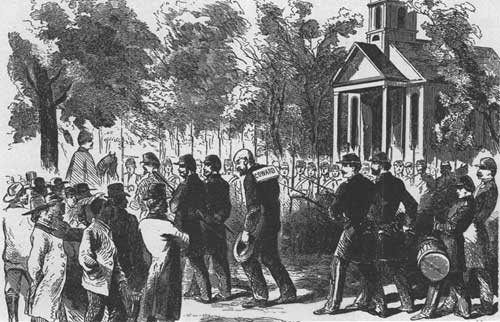

Most penalties meted out in the army were exhibitionistic. Marching

through camp with signs denoting "Thief" or "Coward" were common

punishments. Other penalties included having to wear a barrel shirt,

dragging a ball and chain, and a painful punishment called "bucking and

gagging." After seeing a man sentenced to the last-named humiliation, a

soldier described his plight. "A bayonette or piece of wood was placed

in his mouth and a string tied behind his ears kept it in position"; then "the man was

seated on the ground with his knees drawn up to his body. A piece of

wood is run through his legs, and placing his arms under the stick on

each side of his knees, his hands are then tied in front, and he is as

secure as a trapped rat." In this posture, the culprit would undergo

excruciating pain for several hours.

Long jail terms, branding, and dishonorable discharges were

punishments generally reserved for deserters, flagrant cowards, or men

repeatedly guilty of insubordination. Far more frequently than might be

imagined was the use of capital punishment. Some 500 Civil War soldiers

went before firing squads or mounted crudely constructed gallows.

Two-thirds of that number met their deaths because of the single crime

of desertion. Executions were not merely public; they were usually

mandatory in the case of the condemned man's brigade or division.

Soldiers watching one of their number put to death for a serious offense

were not likely to commit the same offense, the thinking went.

Food was the worst problem in all Civil War armies. It produced the

most criticisms of army life. Apparently the thinking on both sides was

that if the government supplied the basic foodstuffs to the men in large

enough proportions, the troops would make out satisfactorily. Such

thinking worked out well in camp; but when the

armies were on the move, food was almost always scarce.

Every regiment in the field experienced at least one food shortage in

the course of the war, while in some military theaters famines of

lengthy duration took place.

|

A COWARD IS DRUMMED FROM THE

RANKS OF THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC. ILLUSTRATION FROM HARPER'S

WEEKLY, 1862.

|

|

FORBES DRAWING "FALL IN FOR SOUP." (LC)

|

As a rule, the rations varied from mediocre to downright repugnant.

In the autumn of 1862 an Illinois corporal informed the home folk: "The

boys say our 'grub' is enough to make a mule desert, and a hog wish he

had never been born.... Hard bread, bacon and coffee is all we

draw."

Meat was always in short supply—and that may have been good

fortune. Beef was distributed either fresh or pickled with salt. When

chewable, the fresh meat was often eaten raw because it seemed to have

more taste than when cooked.

Pennsylvania soldier John H. Markley observed in 1863 that his salted

beef ration was so strong it could almost walk its self." An Illinois

infantryman examined the meat he received on one occasion and declared

that "one can throw a piece up against a tree and it will just stick

there and quiver and twitch for all the world like one of those

blue-bellied lizards at home will do when you knock him off a fence rail

with a stick."

|

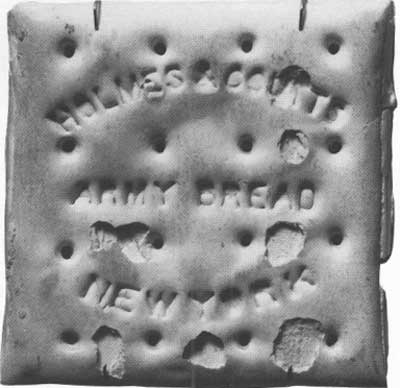

THE INFAMOUS CRACKER KNOWN AS HARDTACK. (COURTESY CHICAGO

HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

The standard bread ration in the Union armies was a

three-inch-square cracker known as hardtack. It was shipped southward in

large crates marked "B. C.," denoting Brigade Commissary. Given the

toughness of the crackers, Billy Yanks were convinced that the letters

actually stood for the date when they were baked. Worse, shipments of

these crackers were usually so infiltrated with "wigglies" that the most

prevalent nickname given to hardtack was "worm castles." One soldier

(perhaps with a degree of exaggeration) stated after the war: "All the

fresh meat we had came in the hard bread . . . and I preferring my game

cooked, used to toast my biscuits."

Civil War soldiers had wonderful powers of adaptation, but most of

them never acclimated to the quality and quantity of Civil War rations. One thoroughly

disgusted private spoke for the majority when he informed his brother:

"We live so mean here, the hard bread is all worms and the meat stinks

like hell . . . and rice two or three times a week & worms as long

as your finger. I liked rice once but god dam the stuff now."

|

FORBES ILLUSTRATION "A CHRISTMAS DINNER" DEPICTS OFF-DUTY SOLDIER

COOKING HIS MEAL IN FRONT OF AN IMPROVISED SHELTER. (LC)

|

Despite such complaints, hunger was a regular companion to several

Union armies and to all Confederate forces in the field. The problem was

not in supply, for both sides had strong agricultural bases.

Transportation breakdowns, graft, corruption, and bureaucratic

incompetence blocked tons of foodstuffs from reaching the front lines.

Soldiers therefore resorted to extreme measures in an effort to calm the

gnawing emptiness in their stomachs.

Some troops were known to subsist for days on green apples and unripe

peaches taken from orchards alongside the route of a march. A South

Carolina colonel stated after the war that he "frequently saw the hungry

Confederates gather up the dirt and corn where a horse had been fed, so

that when he reached his bivouac he could wash out the dirt and gather

the few grains of corn to satisfy in part at least the cravings of

hunger. Hard, dry, parched corn . . was for many days the sole diet of

all."

A Virginian once boiled his greasy haversack in an attempt to make

soup. In 1864 a South Carolina private, overcome by what he termed his

"bold and aggressive appetite," confessed that he had "devoured the

hindquarters of a muskrat with vindictive relish, and looked with

longing eyes upon our adjutant-general's pointer dog."

|

|