|

|

A POOR MAN'S FIGHT

by William Marvel

Initial response to President Lincoln's call for troops proved so

enthusiastic that all the volunteers could not be accommodated. Men were

turned away whom the government would have welcomed two years later, and

in April of 1862 the War Department actually closed its recruiting

offices. Within weeks it became evident that this was a mistake, and the

summer of that year saw massive enlistment drives, but by autumn the

reservoir of purely patriotic recruits had been effectively

exhausted.

The U.S. government answered this lapse with financial inducements

and the threat of conscription. Since the early months of the war,

volunteers had been rewarded with a bounty of $100, most of which was

deferred until the soldier was honorably discharged, but the bounty

seems to have been a significant lure for men from poorer families. The

Militia Act of 1862 required individual states to draft men if their

enlistment quotas fell short, and in the spring of 1863 Congress passed

the first national conscription law, authorizing the central government

to select reluctant recruits. In 1863 the federal bounty was also

increased to $300, in an effort to boost volunteering and reduce the

number of men who might have to be drafted. The men who responded to

these bounties hailed principally from the lower economic strata of

society.

|

HEADQUARTERS OF BLENKER'S BRIGADE. THE BRIGADE WAS MOSTLY

COMPRISED OF FOREIGN-BORN SOLDIERS. (LC)

|

The Conscription Act of 1863 also permitted two means of escape for

those drafted men who could not obtain an exemption for health or hardship.

Anyone who paid a commutation fee of $300—the yearly wage

of a common laborer—would be excused from the draft call in which

he was chosen, though he night be drafted again in the next levy. The

man who wished to secure permanent exemption could simply hire someone

who was willing to enlist as a substitute in his place. These clauses,

and particularly the commutation provision, provoked many to object that

the conflict was "a rich man's war, but a poor man's fight."

The same complaint arose in the South, which instituted a national

draft months earlier than the North." Confederate conscription began in

April of 1862, and that law

also allowed the hiring of substitutes. While it permitted no one to

buy his way out of service with a cash payment, the Southern draft did

excuse men on other grounds, most notably for the ownership of a certain

number of slaves: that number was changed during the war, from twenty to

fifteen, but it was never reduced to a level consistent with moderate

economic status. As late as the summer of 1864, when Confederate

manpower had ebbed critically, the owner of fifteen slaves could also

pay what amounted to a commutation fee of several hundred dollars to

retain the services of one white overseer.

State and local government officials were also exempted from

Confederate service. In Georgia, for instance, Howell Cobb complained

in 1864 that the governor suffered thousands of justices of the peace,

court clerks, sheriffs, and deputies to continue in office when the

limited business of the courts would permit all those officials to he

replaced by far fewer men who were over the military age. Thousands of

other political favorites had also received exemptions through militia

commissions, Cobb charged.

|

"RECRUITING FOR THE WAR." ILLUSTRATION FROM

FRANK LESLIE'S ILLUSTRATED NEWSPAPER,

MARCH 1864. (LC)

|

The Richmond government offered only token bounties to its volunteers, but in the North

the bounty system expanded with each successive draft call. The federal

bounty of $300 was frequently augmented by state, county, and town

bounties as these municipalities competed for the dwindling supply of

men willing to serve. In some communities volunteers could demand $800

or more just from town officials who dreaded a draft of local citizens,

and many towns paid the commutation fee for their drafted

residents—or funded the cost of substitutes, after the obnoxious

commutation clause was eliminated. By the autumn of 1864 an enlistment

could bring as much as $1,200 to $1,500 dollars.

Ironically, more of the poorest volunteers had already responded to

the lower bounties of 1862, and it was they who did most of the

fighting. The bigger bounties of the war's final months tended to draw

more affluent recruits who might not have volunteered at all without the

prospect of such a windfall, and few of these later troops suffered any

of the privations or dangers endured by their predecessors.

While wealthy and politically connected Southeners frequently

managed to avoid military service through the entire war, their poorer neighbors usually

escaped conscription only by physical flight. The mountains of Virginia,

Kentucky, Tennessee, and the Carolinas teemed with deserters and draft

evaders, and thousands of Confederate troops had to be diverted to hunt

for them, or to curb their depredations. Isolated regions of

Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida also hosted whole communities of

fugitives. Northern officials complained of similarly troublesome

enclaves in the Midwest or along the Canadian border, to which many draft-age

Union citizens fled as a last resort.

For all the incentives and coercion employed to mobilize armies North

and South, it was the early volunteers who bore the brunt of the war on

both sides." Despite the intellectuals, professionals, and planter

aristocrats who so prominently officered the legions blue and gray, it

was those of the least means who more often shed their blood and

sweat.

|

|

PRIVATE O.W. CHIPMAN, CO. E 75TH NEW YORK REGIMENT. (USAMHI)

|

Civil War soldiers in the early stages of the war went into the army

under the twin motivations of patriotism and enthusiasm. They were

volunteers and proud of it. Yet they proved insufficient in numbers to

satisfy the demands of a rapidly burgeoning war. Hence, in April 1862,

the Confederate States of America enacted the first conscription act in

American history. The Union followed suit eleven months later. Men

forced into the armies by conscription were suspect in loyalty and

behavior. As a result, officers entrusted with getting them to their

units often transported the recruits as if they were prisoners of war. A

veteran New England soldier looked at one bunch of conscripts arriving

at the front and snorted that "such another, depraved, vice-hardened and

desperate set of human beings never before disgraced an army." When a

similar group joined Confederate General Robert E. Lee's army in 1864, a

Virginia artillerist commented: "Some of them looked like they had been

resurrected from the grave, after laying therein for twenty years or

more."

In too many instances as well, a different kind of enlistee came

forth in the latter half of the war. Some joined to escape the onus of

being termed conscripts; others entered the service under pressure from

relatives and friends. An officer in the 70th Indiana sneered early in

1863 that nine-tenths of the new recruits "enlisted just because

somebody else was going, and the other tenth was ashamed to stay at

home."

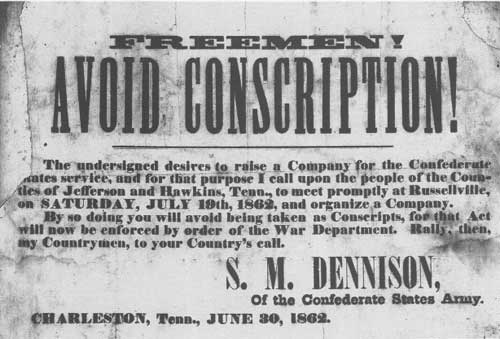

|

THIS POSTER URGED SOUTHERNERS TO "AVOID CONSCRIPTION." (LC)

|

Every Civil War soldier had something to say about

camp life—and it was generally negative. An Ohio volunteer

expressed shock at the lack of morals in his camp. "I shall try to come

out of the army as I went into it—a Christian Man," he reassured

his father, "but I can hardly describe it to you the temptation and

wickedness w'h surrounds a man in camp: Drinking, Swearing, &

Gambling is carried on among Officers and men from the highest to the

lowest."

A Louisiana private in camp near his home solemnly informed his wife:

"Dont never come here as long as you can ceep away, for you will smell

hell here." An Alabama recruit asked his brother to visit him in camp,

but to bring a shotgun with him for his own protection.

Camp shelters varied with the supply and the season. In warm weather

or on the march, most soldiers preferred to sleep in the open to take

advantage of any breeze. For inclement weather, tents were far more

available on the Union side. Yet there never seemed to be enough for

the number of men in need of them.

Three basic types of canvas shelters existed at the time of the

Civil War. The largest was the Sibley tent, bell-shaped and supported

by an upright center pole. It could hold as many as twenty soldiers at a

time—so long as they slept in position like the spokes of a wheel,

with feet to the center and heads toward the tent edge. The "A" or

wedge tent had a horizontal ridge pole and was tall enough to

accommodate a man in standing position. This was a favorite type with

officers. By the end of the war, the dog tent was the most popular shelter. Designed for two

men, it too had a horizontal crossbar at the top but was much more

shallow than the wedge tent.

|

SIBLEY, WALL, AND "A" TENTS AT FEDERAL ENCAMPMENT AT

CUMBERLAND LANDING, VIRGINIA (LC)

|

When armies went into winter quarters, troops on both sides

constructed two kinds of dwellings. One was "bombproofs," consisting of

excavations with roofs built a foot or two above ground level. Most soldiers

spent the cold months in log huts reminiscent of the homes of frontier pioneers.

Often soldiers gave their winter shacks a bit of individualism by

affixing boards over the entrance with house-names scrawled thereon.

"Growlers," "Buzzard Roost," "Sans Souci," and names of famous hotels

were among the favorites.

|

"BOMBPROOF" QUARTERS OF MEN IN FORT SEDGWICK, ALSO KNOW AS

AS FORT HELL. (LC)

|

Homesickness, foul weather, filth, crime, lack of privacy, stern

discipline, and a general absence of godliness quickly produced

criticisms of life in camp.

|

Homesickness, foul weather, filth, crime, lack of privacy, stern

discipline, and a general absence of godliness quickly produced

criticisms of life in camp. Further, oppressive heat and stifling

humidity prevailed during the months of campaigning; mosquitoes and

flies swarmed at every movement; every army

camp in the field had an overpowering stench because of lack of

attention given to latrine procedures and garbage pits. Drinking water

was not always plentiful; when available, it tended to be muddy and

warm.

The winter months were the worst time for many troops. Inactivity

and boredom prevailed. Soldiers no longer found jokes funny. Manners of

compatriots that once were comical became contemptuous.

Conversations lagged simply because the limited subjects had been

exhausted. Discipline became strained as men balked at officers whom

they disliked more with each passing week. Tempers, resentment, and

impatience ran high. Surprisingly large numbers of soldiers actually

came to look forward to springtime and battle as a relief from the dreary and

despairing routine of winter quarters.

|

FEDERAL SOLDIERS AT WINTER QUARTERS. (LC)

|

Officers sought to get around the negatives of camp life by keeping

the men as busy as possible. This meant drill, drill, and more drill,

especially during the first months in the army. The main exercises which

new units practiced were learning to do turns and facings while standing

still and marching, performing the simple rudiments of close-formation

drill, the proper handling of arms, and similar routines. Men learned

how to salute amid stern commands from sergeants to stand erect. New

soldiers struggled with the intricacies of loading weapons "by the

numbers." For some, it was an education; for others, it was total

chaos.

Even the simplest of army maneuvers was a problem for many enlisted

men who were untutored farmboys with an ignorance even of the difference

between their left and right feet. A Pennsylvania enlistee remarked on

his first day's attempt at drill that "when the order 'Right face!' was

given, face met face in inquiring astonishment, and frantic attempts to

obey the order properly made still greater confusion."

One exasperated Georgian swore to a companion that "if he lived to

see the close of this war he meant to get two pups and name one of them

'fall in' and the other 'close up' and as soon as they were old enough

to know their names right well he intended to shoot them both, and thus

put an end to 'fall in' and 'close up.'"

Marches were also considered a necessary

part of drill, and they tended to be a sore trial in every sense.

In the mountains of western Virginia during the war's first summer,

Private John Hollway recounted a march to his Georgia sweetheart: "We

slept on the ground for four nights with only one blanket apiece, and

what was the worst thing that happened to me was that in going up the

mountains I lost one of my shoes in the mud and it was so dark that I

could not find it and then of course I had to carry one until I came

back to camp. You must wonder at soldiers having to do without shoes and

blankets sometimes. I believe men can stand most anything after they get

used to it. The hardest part is getting used to it."

|

CONFEDERATE REGIMENT DRILLING NEAR MOBILE, ALABAMA. (MC)

|

Private Ted Barclay of the 4th Virginia seconded that belief.

Following a severe march in the war's first winter, Barclay jokingly

informed his sister: "Well, here I am at the old camp near Winchester,

broken down, halt, lame, blind, crippled, and whatever else you can

think of—but I am still kicking."

Since the majority of officers and men were starting out the Civil

War as novices (the U.S. Army numbered but 16,000 men at the outbreak of

the war), drill was often akin to the ignorant leading the uneducated.

Green officers giving correct instructions while scores of men were attempting to maintain lines and

proper cadence could be nerve-racking. It was for Captain Daniel

G. Chandler, who was marching his company one day when the men

began rapidly approaching a fence. Chandler could not think of the

proper command to give; and the closer the company got to the fence, the

less Chandler's thinking processes functioned. Finally the frantic

captain bellowed: "Gentlemen, will you please halt!"

The column came to a stop only a few feet from the barrier. Chandler

then shouted: "Gentlemen, we will now take a recess of ten minutes. And

when you fall in, will you please reform on the other side of the

fence!"

Late in July 1861, the 3rd Iowa had one of its first dress parades.

A private in the unit confided in his journal that "the new Adjutant

Laffingwell acted most supremely awkward. The whole Regiment as far as I

noticed, was amused. I could hardly keep a straight face. Take the

Major's blunders together with the adjutant's, and the parade tonight

was a fizzle."

|

DRESS REHEARSAL OF COMPANY K, 4TH REGIMENT, GEORGIA

VOLUNTEER INFANTRY. (PHOTO COURTESY OF GEORGIA DEPT.

OF ARCHIVES AND HISTORY)

|

Little sympathy existed down in the ranks for unknowledgeable

superiors. The greener the officer appeared, the more difficult time he

had at the outset with his men. A young and thoroughly inexperienced

lieutenant was assigned to a new company of rough-hewn soldiers. The

lieutenant was small, seemingly inept, and weak of voice. When he rode

out in front of his troops for the first time, out of the ranks came a

shout: "And a little child shall lead them!" Raucous laughter

followed.

The officer calmly went about the day's duties. Early the next

morning the men were aroused from sleep by an order to prepare for an

all-day march. The announcement ended: "And a little child

shall lead them—on a damned big horse!"

In the first weeks of

any unit's training, accidents with weapons were so commonplace as to

be inevitable. Cavalrymen drilling with sabers regularly pricked their

mounts and frightened the horses into stampedes. Recruits trying to

master the basics of artillery fared little better. Gunners in a

Massachusetts battery one quiet day decided to test their marksmanship

at a large tree on a hilltop 1,000 yards away. They clumsily set

the sights at 1,600 yards and almost annihilated a village on the other

side of the hill.

Even though the bayonet was rarely used in combat (less than half of

1 percent of Civil War battle wounds resulted from blade weapons),

drills with the weapon were an integral part of camp life. The exercises

were apparently wondrous to behold, if a New Hampshire soldier's

account is reliable. He watched his regiment go through the various

steps and lunges. To him the troops looked "like a line

of beings made up about equally of the

frog, the sand-hill crane, the sentinel crab, and the grasshopper;

all of them rapidly jumping, thrusting, swinging, striking,

jerking every which way, and all gone stark mad."

|

UNION SOLDIER'S POSES WITH MUSKET AND BAYONET. (USAMHI)

|

And then, of course, there was the musket, which was the most

important item in a soldier's equipment. Nevertheless, mobilization of

troops too often occurred before units could receive their arms. The

77th Ohio left for war completely unarmed. At the first major engagement

in the western theater, the 16th Iowa arrived on the field with muskets

but without its first issue of ammunition.

The Union armies initially used eighty-one types of muskets. They

ranged in caliber from .45 to .75, and several models antedated the War

of 1812. Soldiers for understandable reasons called the larger caliber

guns "mules" and "pumpkin slingers." When a man prepared to shoot one of these antiquated

pieces, he gripped the weapon as hard as he could, braced himself as

tensely as possible, took aim, shut his eyes tightly, and then pulled

the trigger.

A number of new Union regiments received huge .69 caliber

smoothbores which had been popular for generations. An Iowa newspaperman

examined a shipment of these blunderbusses and concluded: "I think it

would be a master stroke of policy to allow the [Confederates] to steal

them. They are the old-fashioned-brass-mounted-and-of-such-is-the-kingdom-of-Heaven

kind that are infinitely

more dangerous to friend than enemy—will kick further than they

will shoot."

|

"A YANKEE VOLUNTEER" SKETCH BY EDWIN FORBES (LC)

|

The .577 caliber Springfield rifle-musket was the most prevalent

shoulder arm of the Civil War. Next in popularity was the English-made

and extremely similar Enfield. Yet the general prohibition against

firing live ammunition for practice, the tendency of all soldiers to aim

high, and the heavy smoke from the gunpowder of that day reduced

accuracy in battle to a minimum. One authority on logistics asserted

that each Johnny Reb and Billy Yank on an average expended 900 rounds of

lead and 240 pounds of powder in taking out one of the enemy.

During the two-thirds or three-fourths of each year when the men of

blue and gray were in camp, morale underwent severe testing. Late in

1862, Constantine Hege of the 48th North Carolina confessed to his

parents: "Would to God this war might end with the close of the year and

we could all enjoy the blessings of comfortable house and home one time

more. I never knew how to value home until I came in the army."

Furloughs were rare commodities in Civil War armies, largely because

of the distance and time involved in a man getting to and from home.

Confederate General D. H. Hill advocated greater leniency in the granting

of leaves. "If our brave soldiers are not occasionally permitted to

visit their homes," he warned, "the next generation in the South will be

composed of the descendants of skulkers and cowards."

|

"A SOLDIER'S DREAM OF HOME" LITHOGRAPH PUBLISHED BY CURRIER AND IVES.

(LC)

|

Applications for leave flowed steadily through any regimental

headquarters. Most of them were denied. However, in December 1863, a

Maine sergeant used a distinctive approach. He justified his petition on

the basis of holy scripture, citing Deuteronomy 20:7: "And what man is

there that have betrothed a wife, and hath not taken her? Let him go and

return unto his house, lest he die in the battle, and another man take

her." The strategy worked: the sergeant spent Christmas at home.

Soldiers' letters, diaries, and reminiscences make it clear that a

constant search occurred for diversions to overcome the tedium and

monotony of army routine. Neither government was of any assistance in this regard. Unlike

today, no army service agencies, post exchanges, lounges, or libraries

existed for the men; telephones, radio, television, and movies, of

course, were unknown; newspapers were a rarity in camp. Few

entertainment groups ever visited troops in the field. In sum, the

soldiers were left to themselves to combat their own loneliness. That explains why

letter-writing was the most popular occupation of soldiers. It is only during war that

the plain people become articulate to a degree comparable to the upper

classes. Johnny Rebs and Billy Yanks wrote about camp life, battles,

sickness, the weather, and anything else they

had seen or thought. Interspersed throughout the letters would be

questions about conditions back home: the health of family members, the

progress of the crops, and the like. Some of the letters were models of

literary excellence; others were so badly composed, especially with

phonetic spelling, as to be impossible to translate. The great majority

of Civil War letters lay between those extremes, with tendencies toward

the more illiterate side.

|

"NEWS FROM THE FRONT" ILLUSTRATION BY EDWIN FORBES. (LC)

|

|

A LETTER FROM DYING SOLDIER J. R. MONTGOMERY TO HIS

FATHER IN MISSISSIPPI. (MC)

|

In October 1861, Private Charles Futch told his brother, who was

serving in another unit: "John I want you to write to me more plainer

than you have bin a writing." Charles added that he had carried a

bundle of John's letters through two regiments but that "they was not a

man that could even read the date of the month."

An Alabama soldier likewise rebuked his wife mildly for her

handwriting. "I had not a like to maid out half of yourre words," he

informed her, "theare is some that I hant maid out yet."

When a Federal army was undergoing reorganization, a Billy Yank

stated: "They are deviding the army up into corpses." Medical terms

always proved troublesome for many writers. "Tifoid feaver" was a

better-than-usual rendition for one of the war's most dreaded diseases.

Pneumonia once appeared as "new mornion," and hospital was often "horse

pittle." The most prevalent of all soldier illnesses, diarrhea, produced

the greatest variety of spellings. One Union soldier got both his

spelling and his meaning confused when he told his wife: "I am well at

the present with the exception I have got the Dyerear and I hope these

lines will find you the same."

A letter was the sole contact with loved ones. One soldier stated to

his cousin: "I never thought so much of letters

as I have since I have been here. The monotony of camp life would be

almost intolerable were it not for these friendly letters." A

Connecticut private expressed a similar sentiment more dramatically:

"The soldier looks upon a letter from home as a perfect God

send—sent as it were, by some kind ministering Angel Spirit, to

cheer his dark and weary hours."

|

UNION OFFICERS OF COMPANY C, 1ST CONNECTICUT ARTILLERY. (LC)

|

This was also the first time in American history that so large a

percentage of the common folk had been pulled away from home. Soldiers were seeing

new things and living in an unusual environment. They were in a

flashing, strange world whose sights they wished to share with the

homefolk. So they wrote letters—tens of thousands of them—and

they commented on every possible subject with oftentimes pointed

language.

|

MEMBERS OF "RICHMOND GRAYS" ARTILLERY (MC)

|

A young Billy Yank described his first encounter with the enemy in a

direct and forceful way. "Dear Pa," he wrote, "Went out a Skouting

yesterday. We got to one house where there were five secessionists, they

broke & run and Arch holored out to shoot the ornery suns of biches

and wee all let go at them. They may say what they please, but godamit

Pa it is fun."

Less-than-pleasant campsites always provoked sharp observations. One

foot soldier summarized the sparseness of his regiment's surroundings

and concluded: "To tell the truth we are between sh-t and a sweat out

here." At the same time, men in the ranks were especially sensitive to

unfavorable home front gossip. In June 1864, young John Evans responded

to alleged criticism in his community by writing his wife: "The people

that speaks slack about me may kiss my ass. Mollie, excuse the vulgar

language if you please."

Far more pleasing to the soldiers than writing home was hearing from

home. Mail call took precedence over anything, including food. It was

the only tonic for the chronic homesickness that plagued most men of

blue and gray. In March 1863, a soldier told his wife that he "was

almost down with histericks to hear from home," and later in the war,

when a Minnesota private at last received a letter from his family, he

confessed: "I can never remember of having been so glad

before. I sat down and cried with joy and thankfulness."

More than American servicemen of any other age, Civil War troops

were singing soldiers. Next to letter-writing, music was the most

popular diversion in the army. Men left for war with a song on their

lips; they sang while marching or waiting behind breastworks; they

hummed melodies moving into battle; music swelled from every nighttime

bivouac. That is the

major reason why the conflict of the 1860s sparked more new songs than

any other event in American history. The first Civil War song appeared

three days after the firing on Fort Sumter started the struggle. Four

years later, over 2,000 melodies had been added to the national heritage

and to denominational hymnbooks.

|

SHEET MUSIC COVER FOR "TENTING TONIGHT," A POPULAR SONG FROM

THE CIVIL WAR (LC)

|

Among the best-known songs were "Dixie," "The Battle Hymn of the

Republic, "The Yellow Rose of Texas," "Marching Along," "Listen to the

Mocking Bird," "When Johnny Comes Marching Home Again," "Yankee Doodle,"

"Pop Goes the Weasel," "Maryland My Maryland," "Aura Lee," "Sweet

Evalina," and "The Battle Cry of Freedom." Favorite hymns were "Amazing

Grace," "Rock of Ages," "Nearer My God to Thee," "How Firm a

Foundation," "Praise God from Whom All Blessings Flow," "All Hail the

Power of Jesus's Name," and "O God Our Help in Ages Past."

The truly popular tunes in camp were not stirring airs that folks

back home—and generations of Americans thereafter—sang

inspirationally. The soldiers' favorites of the Civil War were songs of

the heart and soul: "When This Cruel War Is Over," "All Quiet

along the Potomac," "Tenting Tonight on the Old Camp Ground," "Auld

Lang Syne," and the most endearing of all war songs, "Home Sweet

Home."

|

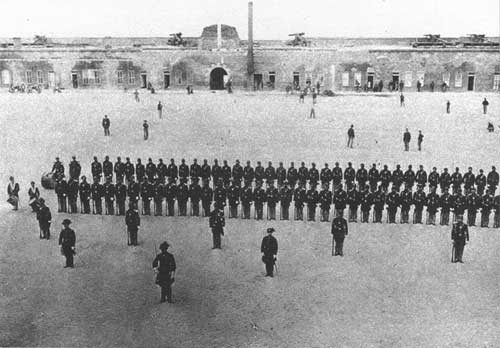

THE BAND OF THE 48TH NEW YORK VOLUNTEER INFATRY PHOTOGRAPHED

AT FORT PULASKI. (NPS)

|

Regimental bands were few, which may have been a blessing. The

scarcity of instruments, the limited talent among band members (more

than one colonel "punished" soldiers for misdemeanors by assigning

them to the band), and weariness from campaigning often resulted in

inferior renditions of the most simple tunes. Fortunately, in any

sizable group of soldiers could be found at least a banjo player, a

fiddler, or a man proficient with the Jew's harp. That sufficed to keep

men entertained with such foot-stomping melodies as "Arkansas Traveler,"

"Billy in the Low Grounds," and "Hell Broke Loose in Georgia."

Civil War soldiers tended to be habitual teasers. Practical jokes

and barbed one-liners were the favorite weapons. Covering a chimney top

so that the occupants of the hut would be smoked out was a regular

practice. Terrifying a recruit on his first nighttime picket duty by

impersonating ghosts was an enjoyable but potentially dangerous prank.

Loading firewood with gunpowder produced some spectacular displays in

camp.

Visitors to an encampment were favorite targets for the jibes of

soldiers. In a rare instance, the civilian might enjoy the last laugh.

Men in the 7th Virginia one quiet day spied an elderly minister, long

white beard flowing in the wind, riding into camp. A good-natured

Virginian immediately called out: "Look out, boys! Here comes Father

Abraham!"

"Young men," the cleric replied quietly when the chortles subsided,

"you are mistaken. I am Saul, the son of Kish, searching for his father's asses,

and I have found them."

Physical contests were a regular part of camp life. Boxing,

broad-jumping, wrestling matches, foot-races, hurdles, and sometimes

free-for-all scuffles all were popular pastimes. Of the competitive

sports, none gained more popularity during the war years than a new game

called baseball. The ball was then softer, but the base runner was out

only when hit by a thrown or batted ball. High scores were therefore the general rule. A

Massachusetts regiment once trounced a New York unit by a 62-20

score. The Texas Rangers loved the sport and played whenever possible

for about six months. They gave up baseball because of Frank Ezell. A

burly Texan with a mean disposition, Ezell pitched and, in the words of

one observer, "came very near knocking the stuffing out of three or four

of the boys, and the boys swore they would not play with him."

|

THIS PHOTOGRAPH FROM FORT PULASKI IS ONE OF THE FIRST SHOWING

A BASEBALL GAME BEING PLAYED (IN BACKGROUND). (NPS)

|

Snowball fights always followed a winter storm, and they did much to

break the tedium of camp life. These engagements usually occurred among small groups, although they might

involve large numbers of men. One such contest erupted between the 2nd

and the 12th New Hampshire. In the action, wrote one bystander, "tents

were wrecked, bones broken, eyes blacked, and teeth knocked out-all in

fun."

|

PLAYING CARDS KEPT THE TROOPS OCCUPIED. (COURTESY SPECIAL COLLECTIONS,

EMORY UNIVERSITY)

|

An Iowa soldier, writing to his father in 1863, philosophized: "There

is one thing certain, the Army will either make a man better or worse

morally speaking." This Midwesterner was pessimistic in the overall

picture of soldier conduct. "There is no mistake but the majority of

soldiers are a hard lot. It would he hard for you to imagine worse than

they are. They have every temptation to do wrong and if a man has not

firmness enough to keep from the excesses common to soldiers he will

soon be as bad as the worst."

Gambling and profanity were natural by-products of camp life.

Dominoes, checkers, and chess were well-liked diversions, but they were

not in the same class with card games. Poker, twenty-one, euchre, and

keno were in evidence any night at any camp. As for profanity, a Billy

Yank observed of his first encampment: "There is so much swearing in

this place it would set anyone against that if from no other motive but

disgust at hearing it." Army life of the 1860s—with all of its

inadequacies and hardships—lent itself to men venting frustrations

in salty language. Few had any hesitation in doing so.

|

MEN OF COMPANY B, 170TH NEW YORK INFANTRY, RELAX IN THE FIELD BY PLAYING

CARDS AND CHECKERS OR READING. (LC)

|

Every army in the Civil War contained some degree of lawlessness.

Theft was the most common offense. It was often stated that no farmer's

henhouse was safe when the 21st Illinois was encamped in the vicinity.

The 6th New York also acquired an unsavory reputation. One officer

described this New York City unit as "the very flower of the Dead

Rabbits, creme de la creme of Bowery society." Rumor circulated that

before a man was accepted in the 6th New York, he had to prove that he

possessed a jail record.

Just before that particular unit departed for war, its colonel gave

the men a pep talk. He held up his gold watch and proclaimed that

Southern plantation owners all had such luxuries which awaited

confiscation by Union soldiers. Five minutes later, the colonel reached

in his pocket to check on the time and found his watch gone.

|

|