|

|

PRISONERS OF WAR

by James I. Robertson, Jr.

Fear of being captured scarcely entered the minds of Northern and

Southern recruits who entered the armies. Americans had never faced the

problem of significant numbers of prisoners of war. In past conflicts,

those comparatively few enemy troops taken prisoner received battlefield

paroles and generally vanished from the scene. However, the immense

scope of the Civil War broke all traditions with the past. About 410,000

soldiers fell into the hands of the other side. This figure is 4-5 times

greater than the number of American soldiers captured in all of the

nation's other wars combined.

|

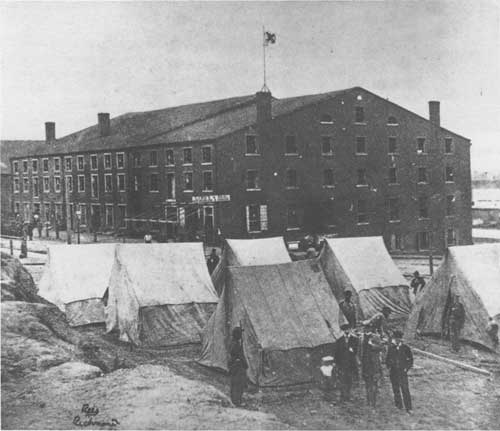

MANY UNION PRISONERS OF WAR WERE HELD AT LIBBY PRISON IN

RICHMOND, VA. (LC)

|

Neither side had any knowledge of what to do with

growing numbers of prisoners. An attempt at an exchange policy,

begun in 1862, collapsed ingloriously the next year. In the

course of the war, both sides were guilty of neglect and

mismanagement resulting in unnecessary suffering and needless

deaths.

Sickness reigned in every one of the 20 to 25 major compounds of the

war. (In all, over 150 prisons came into existence.) A Confederate

surgeon, after inspecting one facility, filed a report that easily could

have applied to any soldier prison. From the crowded conditions,

filthy habits, bad diet and dejected, depressed condition of the

prisoners, their system had become so disordered that the smallest

abrasion of the skin, from the rubbing of a shoe, or from the effects of

the sun, the prick of a splinter or the scratching of a mosquito

bite, in some cases took on a rapid and frightful ulceration and gangrene.

Soldiers unlucky enough to be captured usually went first to a depot

compound such as Point Lookout, Maryland, or Libby Prison in Richmond.

From there most captives were transferred to the prisons that would be

their homes for the remainder of the war.

Prominent Northern prisons were Fort Warren, Mass.; Elmira, N.Y.;

Old Capitol, D.C.; Fort Delaware, Del.; Camp Douglas and Rock Island,

Ill.; and Johnson's Island, Ohio. In the South the major prisons were at

Richmond and Danville, Va.; Salisbury, N.C.; Columbia and Charleston,

S.C.; Andersonville, Ga.; and Camp Ford, Texas.

Prison routine was painfully monotonous. Soldiers arose at dawn,

answered roll call, and received some kind of rations. A second meal

came in the afternoon, with another roll call at sundown. During the

remaining 23 hours of each day, prisoners were left to their thoughts

and improvisations.

Because Andersonville was the largest of the Civil War prisons, it

has received the most attention from generations of writers. It had a

record that remains vile by any standard. The compound was hastily laid

out late in the war and designed for 10,000 prisoners. At one point,

more than 33,000 Federals were crammed into the open and barren

expanse. Most of the captives sent there were "old fish," prisoners

sent from other compounds. Andersonville held a total of 49,400

prisoners during its 13-month existence. Over 13,700 of those men

perished from overcrowding, malnutrition, and insufficient medical

care.

Closely matching Andersonville's death rate, on a smaller scale, was

the Union prison camp at Elmira, New York. Of 12,147 Confederates held

there, 2,980 succumbed from the same causes present at

Andersonville.

Each side accused the other of atrocity, cruelty, and barbarism, yet

neither North nor South made any concerted endeavor to improve

conditions.

As one would expect, soldiers' opinions of prison life were

consistently negative. Inmates referred to various

prison administrators as "the little snotty dog," an "Ass of a

Lieut." and "a most savage looking man," "a vulgar, coarse brute," and

"the greatest scoundrel that ever went unhung." Speaking of a trio of

officials at Fort Delaware, a Tennessee prisoner asserted: "I Dont Think

Thar is any Place in Hell Hot anuf for Thos 3 men."

|

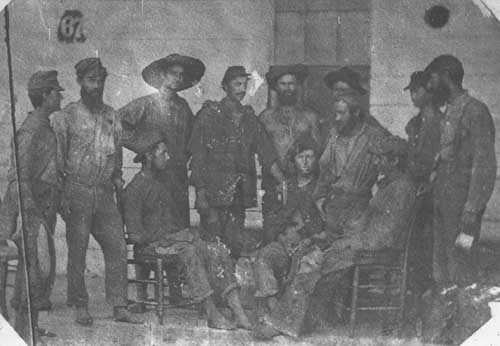

A PHOTOGRAPH OF RELEASED PRISONERS OF WAR. (LC)

|

In the case of the guards

at Andersonville, a Federal prisoner stated that "we are under

the Malishia & their ages range from 10 to 75 & they are the

Dambst set of men I ever had the Luck to fall in with yet."

Rations issued to Federal officer-prisoners at Libby, a New Englander

stated, "consisted of about twenty-two ounces of bread and thirty ounces

of meat for each week. We had something else that they gave us one

week; I do not know what the name of it was." A Confederate at Camp

Douglas in Chicago was explicit about some meat he received: a hunk of

mule neck with the hair still attached.

No doubt exists but that all prisoners fought a constant battle

against vermin. A New York officer found fleas to be particularly

obnoxious. "The beasts crawled over the ground from body to body, and

their attacks seemed to become more aggravating as the men became more

emaciated. By daylight, they could be picked off . . . but in the

darkness there was nothing to do but suffer with patience."

Literally hundreds of "memoirs" by former prisoners of war appeared

in print after the Civil War. The authenticity and accuracy of the

majority have always been in question. Each former prisoner who picked

up pen and paper seemed to feel duty bound to present a more horrible

picture of conditions than did the last writer. These accounts in most

instances were propagandistic and political; they fed the flames of a

controversy that rages still.

Of the 215,000 Johnny Rebs and 195,000 Billy Yanks

taken prisoner in the Civil War, 56,000 died in confinement. The prison

death rate is less than that of most military hospitals at the time.

Yet so many of those incarcerated soldiers lost their lives through

incompetence and indifference that beclouds the whole prison subject

with deep sadness.

George F. Root's "Tramp! Tramp! Tramp!" was one of the best-known

war songs of the 1860s because it was written from the viewpoint of a

prisoner of war whose feelings mirrored those of the captured men of

both sides. The opening lines are:

In the prison cell I sit, thinking,

Mother dear, of you,

And our bright and happy

house so far away."

And the tears they fill my eyes,

spite of all that I can do,

Tho' I try to cheer my comrades

and be gay.

|

|

TWICE AS MANY MEN DIED BEHIND THE LINES OF ILLNESS OR DISEASE THAN IN

BATTLE. (LC)

|

Sickness and insufficient medical treatment were the worst enemies

that Johnny Rebs and Billy Yanks faced.

Midway through the Civil War a Southern private swore that he "had

rather face the Yankees than the sickness and there is always more men

dies of sickness than in battle." This soldier was tragically correct.

For every man killed in action during the Civil War, two died behind the

lines of illness and disease. Extant records show over 6,000,000

reported cases of sickness in the Union armies alone. Surgeon Joseph

Jones tabulated that every Confederate soldier was ill an average of six

times in the course of the war.

Several factors, each with major impact, accounted for the high

incidence of sickness. The ease with which a man could enter the army in

the first half of the war, the poor condition of many of the recruits,

and the abysmal camp conditions were the first causes. Encampment sites

were selected primarily for military reasons and rarely for health

considerations. Such locations tended to be used repeatedly. Inadequate

drainage, ignorance of sanitation practices, plus the natural

carelessness of life in camp added to the setting for widespread

illness. Exposure to the elements, general filth, improper diet, and

always-present vermin compounded the situation. A woeful lack of medical

knowledge, critical shortage of army surgeons, and total inexperience in

dealing with both traumatic injuries and large numbers of incapacitated

soldiers further intensified four years of human suffering. Only hints

at that time existed that unseeable objects called germs played any part

in sickness or infection. That flies and mosquitoes might be carriers of

disease was widely regarded as preposterous.

|

THE CONFEDERATE CHIMBORAZO HOSPITAL IN RICHMOND, VIRGINIA. (LC)

|

Before they heard their first hostile shots, the soldiers encountered

two onslaughts of illness. First were the so called "childhood diseases"

that struck the farmboys and others who had accumulated no immunities.

Chicken pox, measles, mumps, and whooping cough plowed through new

regiments in epidemic proportions. Measles was the deadliest of these

diseases. An Iowa soldier visited a warehouse where one batch of measles

cases had been deposited. "About 100 sick men crowded into a room 60 by

100 feet in all stages of measles. The poor boys lying on the hard

floor, with only one or two blankets under them, not even straw, and

anything they could find for a pillow. Many sick and vomiting, many

already showing unmistakable signs of blood poisoning."

While the troops struggled helplessly against the first wave of

diseases, they also had to endure "camp illnesses" triggered by impure

water, exposure, poor food, mosquitoes, and general filth. Such

conditions produced the biggest killers of the Civil War: diarrhea,

dysentery, typhoid fever, and pneumonia.

|

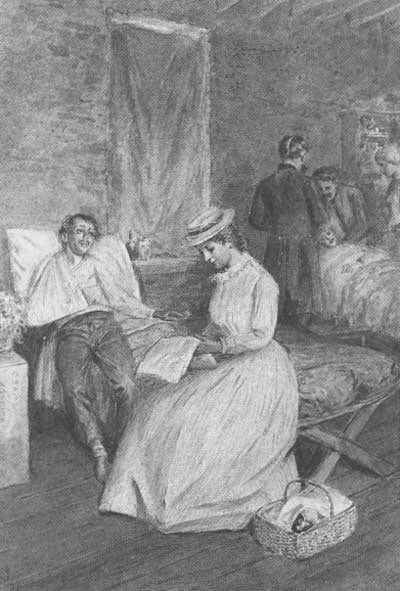

PAINTING BY W. L. SHEPPARD TITLED "IN THE HOSPITAL, 1861." (MC)

|

Diarrhea was practically a universal epidemic among Civil War

soldiers. It was at the least debilitating and at the most deadly. Army

physicians were never able to find any suitable cure or even to provide

a semblance of relief. This led an Illinois soldier to remark on one

occasion that a compatriot's bowels "needs turning ron side out and

washing with soap suds." After the war an Iowa soldier noted humorously

that countless numbers of men "literally had no stomach for

fighting."

Medical knowledge was at such a primitive stage in the 1860s that the

practice of army medicine devolved into administering drugs and potions

of all known types and in heavy quantities. One New England surgeon

habitually plied men suffering from any ailment (including diarrhea)

with dose after dose of castor oil. As he did so, he would state

cheerily: "Down with it, my boy. The more you take, the less I

carry."

Most Civil War soldiers were unaware of the severe handicaps under

which the doctors labored, especially during a battle. In the rude and

makeshift field hospitals only a mile or two behind the battle lines,

physicians toiled long hours to rescue life from the debris of war.

Field surgeons performed three basic tasks only. They probed for

embedded missiles (usually with their fingers), and they employed

unsophisticated ligatures in an effort to control hemorrhaging. However,

three-fourths of a surgeon's time was spent in amputating mangled arms

and legs. Little was known at the time of the principle of setting

broken bones; of greater impact was the simple rationale that the

wounded were too many and the doctors too few to allow prolonged

treatment of a serious injury to an extremity. It was quicker, and the

prognosis seemed just as favorable, to remove the limb in question.

|

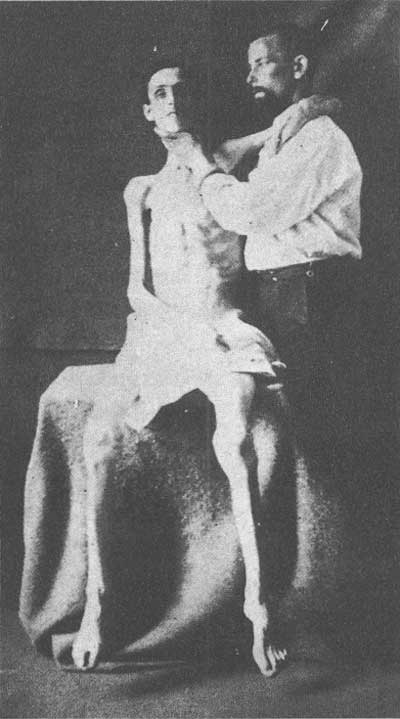

PHOTOGRAPH OF UNION POW TAKEN AT THE U. S. GENERAL HOSPITAL IN

ANNAPOLIS, MARYLAND. (LC)

|

|

"VOLUNTEERS ASSISTING THE WOUNDED IN THE FIELD OF BATTLE," ILLUSTRATION

BY A. R WAUD. (LC)

|

Any soldier who saw a field hospital never forgot it. At the first

major battle of the war, Lieutenant William Blackford and his Virginia

cavalry company patrolled one of the vital roads. It was early in the

afternoon when Blackford observed that "along a shady little valley

through which our road lay the surgeons had been plying their vocation

all the morning upon the wounded. Tables about breast high had been

erected upon which screaming victims were having legs and arms cut off.

The surgeons and their assistants, stripped to the waist and all

bespattered with blood, stood around, some holding the poor fellows

while others, armed with long bloody knives and saws, cut and sawed away

with frightful rapidity, throwing the mangled limbs on a pile nearby as

soon as removed. Many were stretched on the ground awaiting their turn,

many more were arriving continually . . . while those upon whom

operations had already been performed calmly fanned the flies from their

wounds. The battle roared in front . . . but the prayers, the curses,

the screams, the blood, the flies, the sickening stench of this horrible

little valley were too much for the stomachs of the men, and all along

the column, leaning over the pommels of their saddles, they could be

seen in ecstasies of protest."

Army surgeons were not miracle men: they lacked both the knowledge

and the medications to curb epidemics, to stop the spread of infection,

and to restore health to every man who was ailing. Hence, they were

incompetent in the eyes of many sick soldiers. "Because a man had

enlisted to serve his country," an artilleryman asserted, "it is no

reason he should be treated like a dog by one-horse country doctors who

once they mount shoulder straps, think they are Almighty." A Midwestern

private worked up what he regarded as the supreme criticism when he

stated that "the docterking [was] about in keeping [with] the

Cooking."

The surgeons labored on as best they could in the face of such

damnation. One Confederate physician put the subject in perspective (at

least to his own satisfaction) when he concluded: "Medical Officers are

generally the most unpopular—owing to the fact that they deal with

sick men—the most unreasonable of all animals."

As for those soldiers outspoken in their denunciation of surgeons,

few of them would have considered Dr. George T. Stevens of the 76th New

York pausing in the midst of the 1864 Wilderness campaign in Virginia to

inform his wife: "I see so many grand men dropping one by one. They are

acquaintances and my friends. They look to me for help, and I have to

turn away heartsick at my want of ability to relieve their sufferings. .

. . Oh! can I ever write anything besides these mournful details?

Hundreds of ambulances are coming into town now, and it is almost

midnight. So they come every night."

|

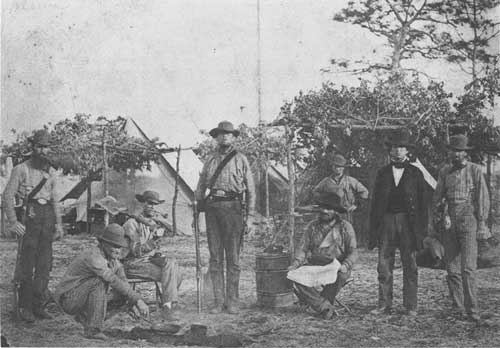

CONFEDERATE CAMP AT PENSACOLA, FLORIDA, 1861 (LC)

|

|

LACK OF CLEANLINESS WAS A MAJOR PROBLEM IN CAMP. HERE, SOLDIERS BATHE

IN THE RIVER. (LC)

|

Lack of adequate clothing brought misery and suffering to thousands

of soldiers. Men in the Union Army of the Potomac likened the winter of

1862-1863 around Fredericksburg, Virginia, to the agony of George

Washington's army at Valley Forge. A member of the 13th New Hampshire

observed: "It is fearful to wake at night, and to hear the sounds made

by the men around you. All night long the sounds go up of men coughing,

moaning and groaning with acute pain. . . . This camp of 100,000 men is

practically a vast hospital."

It is a shocking fact that at least a third of the Southern army was

barefoot at any given time. Commanders worried constantly about the men

suffering from want of shoes, particularly in wintertime. One

Confederate brigadier sought to alleviate the situation by issuing

strips of fresh cowhide to his men to wrap around their feet. The result

of using untreated hide was disastrous, according to one Johnny Reb.

"General Armstad sent me a pair of raw hide shoes the other day and

[they] stretch out at the heel so that when I start down a hill they

whip me nearly to death, they flop up and down. they stink very bad and

I have to keep a bush in my hand to keep the flies off of them."

However, the soldier added, "this is the last of the raw hide, for some

of the boys got hungry last night and boiled them and ate them, so

farewell raw hide shoes."

|

HEADQUARTERS OF THE ARMY OF THE POTOMAC AT BRADY STATION. NOTE BOXING

MATCH IN CENTER. (LC)

|

Unhealthy camp conditions were commonplace. Little opporunity existed

for bathing. Since most soldiers had but one uniform, it appeared a

waste of time to wash oneself in a river and then don the same filthy

rags again. Confederate soldiers suffered harshly in this regard.

Following the 1862 battle of Antietam, Lieutenant James Burnham of

Connecticut told his parents of seeing Confederate prisoners of war for

the first time. "Their hair was long and uncombed and their faces were

thin and cadaverous as though they had been starved to death. It is of

course possible that is the natural look of the race, but it appeared

mightily to me like the result of short fare. They were the dirtiest set

I ever beheld. A regiment of New England paupers could not equal them

for the filth, lice and rags."

The use and misuse of camp latrines—long, open ditches with no

sanitary aspects whatsoever—further promoted germs and disease.

Many soldiers scorned the foul-smelling "sinks," as latrines were

called. Thus did a Virginia soldier write in his diary in 1862: "On

rolling up my bed this morning I found I had been lying in—I wont

say what—something though that didn't smell like milk and

peaches."

A contaminated atmosphere where tens of thousands of unwashed

soldiers congregated led to an endless horde of flies, mosquitoes,

gnats, lice, and fleas, which themselves became additional hazards to

health. "There are more flies here than I ever saw any where before," an

Alabama volunteer wrote his wife. "Sometimes I ... commence killing them

but as I believe forty come to everyone's funeral I have given it up as

a bad job."

Few soldiers escaped infestation by fleas. A Mississippi soldier,

returning to camp from a short furlough, wrote about the onslaught of

fleas he encountered. "They hay most Eate me up since I came Back her,"

he declared. "I was fresh to them so they pitched in." Fleas likewise

plagued an Alabama private and led to an interesting commentary by that

man to his wife: "I think there are 50 on my person at this time, but

you know they never did trouble me. . . . May, I have thought of you

often while mashing fleas."

Vermin swarmed wherever an army assembled. Battle was no deterrent. A

Federal colonel once waved his men into action with a sword in one hand

while he feverishly scratched himself with the other hand.

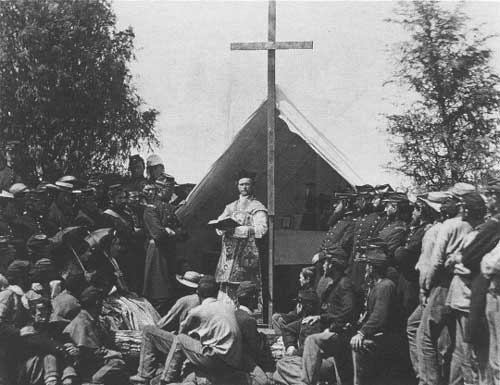

Civil War soldiers took varying degrees of refuge in religion. For

most troops, religion was a personal matter. Joining the army only

strengthened their conviction to follow home-learned Christian

principles down the uncertain road of war. Hence, faith in God became

the single greatest instrument in the maintenance of morale inside the

armies. The evangelical sects of the nineteenth century were active and

large. From the writings of Johnny Rebs and Billy Yanks comes the

inescapable conclusion that faith was more prevalent in the ranks than

is the case in modern times.

|

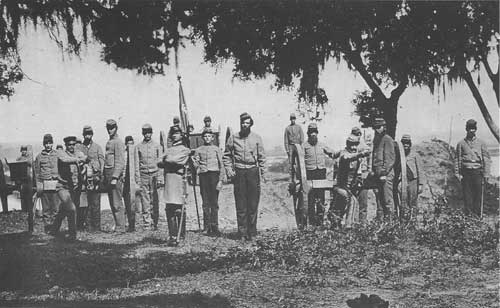

CONFEDERATE ARTILLERY PICTURED NEAR CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA IN 1863.

(LC)

|

A few men, of course, dismissed religion as a weakness or scorned

faith after witnessing the hell of battle or experiencing the loss of

friends and comrades. Some soldiers just grew weary of the loud

evangelicalism present in camp. Among the latter was Sergeant James

Williams of the 21st Alabama. After having to endure the noise of yet

another nightly camp meeting, Williams sneered: "It seems to me that

where ever I go I can never get rid of the Psalm-singers ... making

night hideous with their horrid nasal twang butchering bad music, and

insulting the Most High with hypocritical and 'impious prayers!'"

Williams had no confidence either in the fighting qualities of the

openly devout. "If I had to go off on a dangerous expedition to-night,

I'd rather take an old granny than any of them—Give me a good

'sinner' to stand by me when the hour of danger comes."

Far larger numbers of soldiers found in religion a sanctuary from war

and all of its uncertainties. One such Confederate, James Parrott of the

16th Tennessee, reassured his wife: "I can say thank God that I have

never bin harmed, when I go into a fite I say God be my helper and when

I come out I say thank God I feel like he has bin with mee."

|

FATHER THOMAS MOONEY PERFORMS SUNDAY MASS FOR THE 69TH NEW YORK. (LC)

|

|

1871 LITHOGRAPH OF CONRAD CHAPMAN'S "THE 3RD KENTUCKY (CSA) AT MESS

BEFORE CORINTH." (LC)

|

|

"PRAYER IN STONEWALL JACKSON'S CAMP." (MC)

|

Reading testaments was a common occurrence in camp. Chaplains usually

spoke to large and attentive audiences at a field service. Religious

tracts found eager takers whenever they were circulated. Many soldiers,

unsure of the unknowns of tomorrow, seconded the sentiments of Abraham

Lincoln, who once acknowledged: "I have often been driven to my knees by

the realization that I had nowhere else to go."

The personal religion of Johnny Rebs and Billy Yanks manifested

itself in intimate and sometimes interesting prayers. Just before the

start of one large battle, a group of North Carolinians asked a

compatriot who was also a self-styled preacher to lead them in prayer.

The man removed his hat, looked heavenward, and intoned: "Lord, if you

ain't with us, don't be agin us. Just step aside and watch the damndest

fight you are ever likely to see!"

The bulwarks of faith in the armies were supposed to be the

chaplains. Yet evidence is strong that many of the initial appointees

did not practice what they preached. An Englishman serving in the

Confederate army termed the first group of Southern chaplains "a race of

loud mouthed ranters . . . offensively loquacious upon every topic of

life save man's salvation." A hospital chaplain made a habit of sitting

on the edge of some soldier's cot, telling the man he looked close to

death, and urging him to prepare to meet his Maker. This was too much

for one recuperating soldier; he threw a plate at the cleric and told

him to go to hell.

Lack of scruples characterized a number of early army ministers.

Court-martial records show that some descended to horse-stealing,

speculation, theft, and desertion. One rainy evening, a chaplain entered

a stud-poker game in the camp of a Connecticut unit and promptly cleaned

out an entire company.

Such behavior brought momentary discredit to the whole profession and

a variety of nicknames to individual offenders. One chaplain remembered

only for hellfire-and-brimstone sermons was dubbed "The Great

Thunderer"; another who continually warned soldiers of imminent death

was called "Death on a Pale Horse"; and when the chaplain of the 127th

New York began charging the troops a penny apiece for each letter he

mailed home for them, the soldiers contemptuously christened him "One

Cent by God."

Fortunately, these incompetents eventually left the armies.

The men who remained—known affectionately as "Holy Joe" or "Holy

John"—proved to be sincerely motivated, unpretentious, filled with

both righteousness and patriotism, and able to bring a sense of caring

in an aura of callous warfare. The good chaplains performed a wide

variety of activities: holding prayer meetings and church services on a

regular basis, visiting the sick in camp and hospital, counseling with

individual soldiers, distributing religious tracts and testaments,

writing and reading letters for soldiers, delivering mail, enduring the

hardships of their men on the march and in battle, and making of

themselves an example for the troops to follow. Chaplains were generally

judged far more for what they did than for what they said; and if they

turned out to be good preachers as well, that was an extra point in

their favor.

|

A GROUP OF CONFEDERATE SOLDIERS POSE FOR A WAR PHOTOGRAPHER. (LC)

|

The kindness of chaplains to soldiers was never forgotten. On a

particularly trying march in 1863, Chaplain William E. Wiatt of the 26th

Virginia carried the guns of several weakened men in his regiment.

|

The kindness of chaplains to soldiers was never forgotten. On a

particularly trying march in 1863, Chaplain William E. Wiatt of the 26th

Virginia carried the guns of several weakened men in his regiment. This

exertion so sapped the Baptist cleric that he was confined to bed for a

week. Yet Wiatt's actions won him scores of lifelong friends.

Another example was the Reverend Arthur Fuller of the 16th

Massachusetts. He fell at Fredericksburg, Virginia, musket in hand,

while participating in a skirmish. Two days earlier, Fuller had received

his discharge from service. He had delayed his departure to remain with

his friends a little longer. Similarly, Mississippi Chaplain A. G.

Burrows returned to camp with the troops after a skirmish with Federals.

Burrows had a four-inch gash in his skull. "It was winter and bitter

cold," a fellow minister noted. "The wounded chaplain had no overcoat.

His other coat was thin and ragged. All his clothing was worn out."

Burrows died shortly thereafter, "his devotion to his God and his

country" having "cost him his life."

Two great revivals swept through the Confederate armies in the course

of the war, and lesser religious awakenings marked other armies at some

point. These movements doubtless elevated faith as well as morality. Yet

evidence is strong that such improvements too often were temporary. Evil

seems to have remained just as persistent in an army camp as the crusade

for righteousness.

|

|