|

|

WOMEN OF THE WAR

by William Marvel

Until 1861, the part played by women in American wars had been only

incidental. For both political and sociological reasons, that began to

change almost with the opening of the guns at Fort Sumter.

Until the first half of the nineteenth century, the individual family

had constituted the principal unit of production in a society that was

largely self-sufficient. Within the family, men tended to provide the

raw materials while women served as the manufacturers of finished

products. The evolution of industrial society had freed millions of

women from their roles as the producers of goods, and a simultaneous,

gradual reduction in the size of families somewhat lessened the burdens

of motherhood. These combined factors allowed many women the leisure to

pursue other callings. By midcentury American girls were accorded the

"unprecedented right to equal education in public schools, and female

seminaries began springing up across the country."

Added to these societal changes was the movement toward female

equality: an 1848 convention in Seneca Falls, New York, had marked the

opening of the women's rights movement. That movement arose at least

partly as an outgrowth of the abolitionist crusade, which usurped its

momentum for another generation, but the Civil War posed an opportunity

for women to express and exercise their independence. It is no surprise

that the founders of the women's movement and the prominent women of the

war included a disproportionate number of Quakers and Universalists, for

those denominations had long since begun to shed the veil of male

supremacy.

Much attention has been devoted to the women who disguised themselves

and served under arms in the Union and Confederate armies. The lack of

extensive physical examinations permitted such masquerades in far

greater numbers than might have been possible in later wars, and some

women inevitably saw combat: a shallow grave uncovered near the Shiloh

battlefield in 1934 contained the skeletons of nine Union soldiers, one

of which was identified as that of a woman.

|

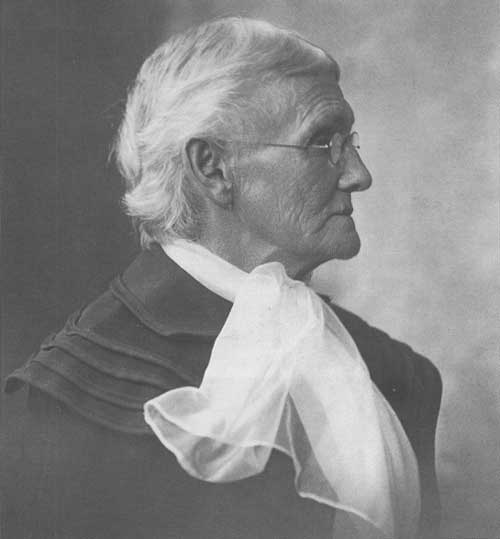

MARY ANN BICKERDYKE (LC)

|

Rare wives like Kady Brownell, of Rhode Island, actually marched

openly with their husbands on the parade ground and, reputedly, into

battle. Armed women, however, were relatively few, disguised or not. Far

more women contributed by replacing the men who left civilian employment

for the army. Particularly in the Midwest and the South, great numbers

of women could be found driving teams and harvesting crops; one Iowa

observer recalled seeing more women in the fields than men. North and

South, women turned their energy toward the production of uniforms,

equipment, and medical supplies, while still others on both sides filled

vacant clerkships in government bureaus. In the North, women composed

much of the labor force that engaged in the manufacture of ammunition,

and dozens of them were killed in the accidental explosion of a

munitions factory at Pittsburgh in September of 1862.

The single greatest service that women provided lay in the field of

humanitarian relief. Within a week of the outbreak of war Dorothea Dix

proposed the creation of a corps of army nurses, and she was named

superintendent of those nurses. Until then the care of sick and wounded

soldiers had been the domain of men alone, but the war changed all that.

Northern women flocked to hospitals by the thousands, both under

official auspices and, like Clara Barton, independently. An 1862

Confederate law provided for female nurses wherever possible, and

Southern women rose to the formal command of large military

facilities.

Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman to earn a medical degree, drew

3,000 women to a meeting in New York two weeks after Fort Sumter fell,

and that meeting led to the formation of a group that became the

Sanitary Commission, which saw to the general health and comfort of the

U.S. soldier. In Chicago Jane Hoge and Mary Livermore organized the

Northwestern Sanitary Commission, and their most famous field agent was

Mary Ann Bickerdyke, known to the soldiers of the western army as Mother

Bickerdyke. She was the only woman William Sherman would allow at the

front, and when his army marched in the Grand Review in 1865 she rode a

horse at the head of the Fifteenth Corps. In the South, women gathered

in smaller, local relief societies devoted to the health and comfort of

their men in the ranks, but the dispersion of their efforts limited

their effectiveness.

Dr. Mary Walker, a young medical school graduate, began the war by

volunteering in Washington hospitals. From there she moved into

battlefield hospitals, and in September of 1863 she was appointed

assistant surgeon of an Ohio regiment. After the war she was awarded the

Medal of Honor for meritorious service.

Bold, determined souls like Barton and Walker blazed a wide path for

women who wished to claim their place in society. They served as clarion

examples for their sisters, and their work challenged male domination of

the medical profession in particular. In postwar years the veterans did

not forget the devotion of their wartime nurses, often welcoming them as

honorary members of their fraternal associations, and that camaraderie

may have initiated a transformation in the way American men viewed the

opposite sex.

|

The Civil War had to run its bloody course so that the destiny of the

United States could be determined. A bloody course it truly was. Almost

700,000 American soldiers of blue and gray gave their lives in the Civil

War to define the nation's destiny. If civil war erupted today in

America and total losses were in the same proportion to population now

as they were then, the Northern states would lose 4,000,000 men while

the Southern states would suffer 11,000,000 casualties.

|

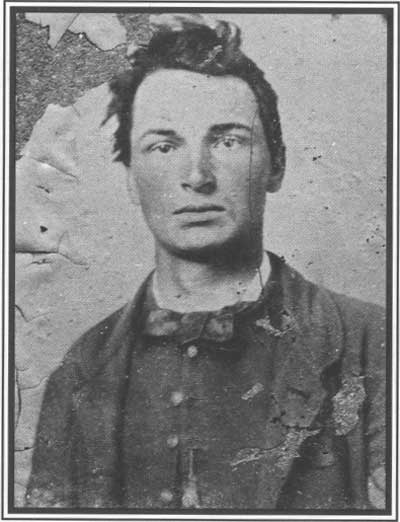

DANIEL COULET ENLISTED IN SEPTEMBER 1861 AT AGE TWENTY WITH THE 40TH

OHIO VOLUNTEER INFANTRY. HE DIED OF WOUNDS RECEIVED AT THE BATTLE OF

LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN, NOVEMBER 1863. (COURTESY OF DENNIS KEESEE)

|

|

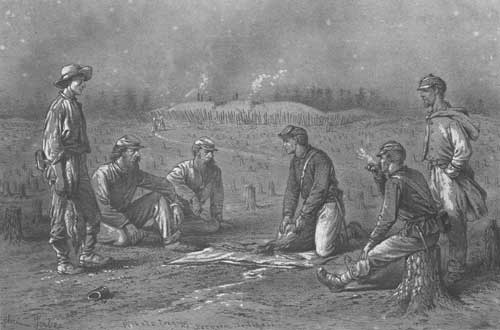

DRAWING BY EDWIN FORBES OF PICKETS TRADING BETWEEN THE LINES. (LC)

|

Four times more Americans were casualties at the 1862 battle of

Antietam than in the 1944 D-Day invasion of France. Over 125 Civil War

regiments suffered losses of 50 percent or higher in a single

engagement. At Gettysburg the 1st Minnesota and 26th North Carolina each

suffered 85 percent losses. Ninety-one pairs of brothers served in an

Illinois regiment. Of these, 43 pairs were killed in action and 15 pairs

died of sickness.

With the passing years the men of blue and gray aged gracefully. Time

healed most wounds a nd obliterated scars of mind and body.

|

They are all gone now—the last of them died in the

1950s—but they left something for us to remember and to use. From

the fractures of that war came common ties. All that the survivors on

both sides endured ultimately became a common bond that brought them

together. The millions of farmboys, students, and clerks who went home

from that terrible storm of fire and blood realized that they had been

witness to the greatest event of the century. As time cooled passions,

shared experiences helped to forge a oneness. A post war brotherhood

took root, and it became more concrete than the ties of sectional

allegiance had been.

With the passing years the men of blue and gray aged gracefully. Time

healed most wounds and obliterated scars of mind and body. "Some good to

the world must come from such sacrifice," a North Carolina veteran

observed late in life; and when Tennessean John Mason was asked in the

1920s about his Civil War experiences, the bent and gray-haired

Confederate responded: "I fired a cannon. I hope I never killed

anyone."

|

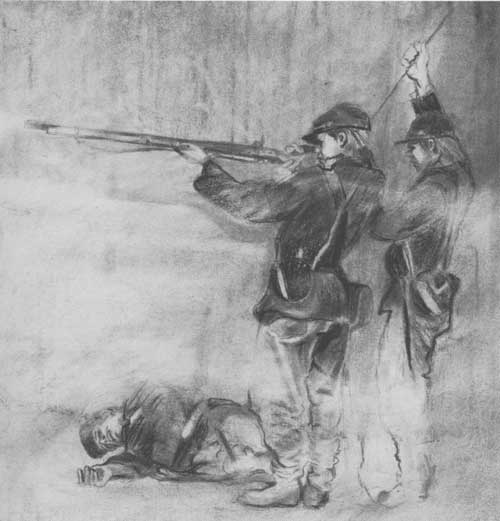

MANY SOLDIERS LIED ABOUT THEIR AGE IN ORDER TO JOIN IN THE WAR EFFORT.

(ILLUSTRATION BY MARK KAUFMAN)

|

|

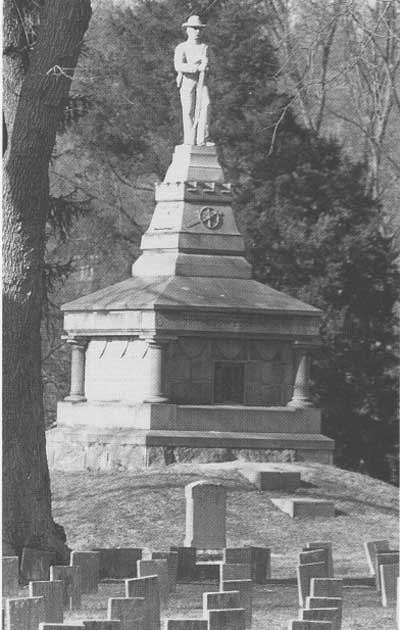

CONFEDERATE CEMETERY AT FREDERICKSBURG, VIRGINIA. (MPS)

|

|

"HOME COMING, 1865" PAINTING BY W. T. SHEPPARD. (MC)

|

From a common pride came a common legacy, and they remain foundations

of a nation of united states. Johnny Rebs and Billy Yanks demonstrated

for all time how to endure, to fight, to suffer, to die, to remember,

and to forgive. In the fire and ashes of a great civil war, the strength

of the common folk stood supreme. Because of that, and because of them,

America still lives.

|

Back cover: Painting by Mark Kaufman, 203 Brandywine Blvd.,

Wilmington, DE

|

|

|