|

LIFE IN CIVIL WAR AMERICA

The coming of the Civil War was not unanticipated because the sectional

conflict had been at the center of American politics for several

decades before the firing on Ft. Sumter in April 1861. Yet war was a

rude awakening for most Americans who had not realized that Lincoln's

election in 1860 and secession fever would culminate in armed struggle

for Confederate independence. Few imagined that this conflict would

escalate into a full-scale bid to destroy slavery and result in waves of

African Americans struggling openly for full and equal rights as

citizens, many through the dangerous rite of passage as Union soldiers.

Hardly anyone imagined that the conflict would result in the kind of

total war which would absorb the entire nation for over four years and

deprive the country and families of half a million young men, as the

wartime generation and those who followed grappled with the several and

severe meanings of civil war.

|

CHARLESTONIANS WATCHED THE CONFEDERATE BOMBARDMENT OF FT. SUMTER

FROM ROOFTOPS OVERLOOKING THE BAY. (LC)

|

This conflict became all-encompassing, touching the lives of nearly

all Americans—slave and free, black and white, native-born and

immigrant, property owner and wage earner, man and woman, adult and

child—dramatically transformed by this momentous battle to decide

the future of the continent. Like many armed engagements, even its name

reflected dispute. Lincoln and his government wished to minimize

secession, hoping to ignore the sovereignty of the Confederacy. But

certainly the "War for the Union," or the "Civil War" was the most

popular Yankee appellation. Ardent Confederates had choice names: the

"Second American Revolution, "the "War of Northern Aggression," the "War

for Southern Independence," the "War for States' Rights." Most

Americans, horrified by the way the nation was ripped apart, viewed it

as "the Brother's War." Indeed, the conflict deeply divided hundreds of

households and thousands of kinship networks when volunteers were

needed.

Symbolic of this division was that four of Lincoln's brothers-in-law

wore Confederate uniforms. Despite Mary Todd Lincoln's staunch devotion

to the Union her southern relations were loyal to the Confederacy. Other

prominent politicians found themselves in complex straits: Senator

George B. Crittenden of Kentucky had two sons fighting in the

war—one a major general for the Confederacy and the other a major

general of the Union. Major Robert Anderson, in charge of federal troops

at Ft. Sumter, was the son-in-law of the governor of Georgia. Across the

bay he faced his artillery instructor at West Point, Confederate General

P. G. T. Beauregard, who fired on his star pupil and former assistant.

Many West Point graduates, friends and roommates, faced one another on

the battlefield as well as serving alongside military school comrades.

(Some wags even believed the outcome of the battle was determined by

the class rank of the generals pitted against one another!) Friendship

and kinship were rent asunder by the great onslaught of the Civil

War.

Childhood was dramatically affected by the onset of war. The

overwhelming youth of the armies on both sides and the way young men

flocked to battle had a generational impact on America. Out of 2,700,000

federal soldiers, over two million were twenty-one or younger and over

a million younger than eighteen. Rough estimates are that 100,000 served

in the Union army at fifteen or younger with 300 under thirteen and 25

under ten. Most of these extremely youthful volunteers were in the drum

and fife corps, but their separation from families and exposure to

deprivation and danger could be traumatizing.

In a sampling of a million federal enlistments, only 46,000 soldiers

were over twenty-five. Youthful officers became a hallmark of the Union

army—with Galusha Pennpacker rising to the rank of brevet major

general at seventeen, too young to vote until the war ended. George

Custer rose to this exalted rank at the age of twenty-one and joined six

other Union generals in their twenties.

Confederates had equally legendary youths in military service.

Brigadier General William P. Roberts of North Carolina rose to his rank

at the age of twenty. Boys in gray were equally common, and Confederate

troops had disproportionate numbers of teenagers as well, but samplings

of rebel ranks indicate that there were larger numbers of men in their

twenties and thirties and a larger group of older soldiers, especially

as the war wore on. In any case, families were stripped of manpower and

communities literally depleted by the war. One town in Wisconsin

witnessed 111 of the 250 registered voters volunteering for the army.

The farm boys of the midwestern states entered the Union ranks in

droves.

But no group was more electrified by the 1860 election than free

blacks. Thomas Hamilton, founder of the New York weekly the

Anglo-African, had warned in March 1860: "We have no hope from

either [of the] political parties. We must rely on ourselves, the

righteousness of our cause, and the advance of just sentiments among the

great masses of the . . . people." But the majority of African Americans

supported Lincoln. The Colored Republican Club of Brooklyn raised a

"Lincoln Liberty Tree" in the summer of 1860, and similar signs of

African American solidarity dotted the northeastern seaboard and Old

Northwest riversides. Most eligible black voters cast their ballots for

Lincoln.

Frederick Douglass crowed over Lincoln's victory: "For fifty years

the country has taken the law from the lips of an exacting, haughty and

imperious slave oligarchy . . . . Lincoln's election has vitiated their

authority, and broken their power." The threat of disunion buoyed black

activists during postelection chaos. In the North, they rallied to the

cry, "BREAK EVERY YOKE." Blacks saw the split in the Union as a sign

that the North could no longer tolerate slaveholders' tyranny.

|

THE MAJORITY OF FEDERAL ENLISTEES WERE UNDER TWENTY-FIVE. THIS

PHOTOGRAPH OF UNION OFFICERS INCLUDES GEORGE A. CUSTER (RIGHT FRONT),

WHO BECAME A BREVET MAJOR GENERAL AT TWENTY-ONE. (LC)

|

White Southerners chose to interpret Lincoln's election and the

response to secession in equally strong terms. Further, slaveholders

feared the undermining of their authority, which armed federal

intervention represented. The slave grapevine rattled with the threat of

war. In the Deep South, conspiracies and plots spontaneously combusted

in the war's first few weeks. On May 14, 1861, a planter in Jefferson

County, Mississippi, wrote to the governor concerning his fears: "A plot

has been discovered and [alrea]dy three Negroes have gone the way of all

flesh or rather paid the penalty by the forfeiture of their lives." He

argued that 11,000 slaves surrounding less than a thousand whites might

foment devastating insurrection. The plotters' "diabolical" plans

included killing white males, capturing white females, and marching "up

the river to meet 'Mr. Linkin' bearing off booty such things as

they could carry." Planter paranoia prevailed in the Delta

countryside.

|

UNION MOBS TARRED AND FEATHERED A PRO-CONFEDERATE NEWSPAPER EDITOR, AS

SHOWN IN THIS FRANK LESLIE ILLUSTRATION (FW)

|

By the end of the long hot summer of 1861, a plot was uncovered in

Adams County, where a Mississippi woman reported "that a miserable,

sneaking abolitionist has been at the bottom of this whole affair. I

hope that he will be caught and burned alive." Alarm ran rampant in the

rural interior, where husbands and sons had been lured off to the

Confederate army and blacks routinely outnumbered whites twenty to one.

Local investigators determined that this home grown conspiracy was the

work of slaves, planning to rise up against masters in the event of

federal invasion. By mid-September, Home Guards and Vigilance Committees

in Adams County were on the offensive and nearby counties on alert.

Reportedly twenty-seven black men were hung. A woman writing from her

plantation confided, "It is kept very still, not to be in the

papers."

With the outbreak of war, the Confederacy required the utmost

cooperation of all her citizens, especially from the sons and daughters

of the planter class. The newly formed government did not want hysteria

in the countryside and slave owners arming themselves against their own

slaves. As a result, evidence of insurrectionary activity was repressed.

Despite the protracted efforts of Confederate loyalists to portray only

harmony among owner and owned, despite best efforts to rally blacks to

the Stars and Bars, we know not all African Americans were devoted

servants to Confederate masters, as painted by wartime rhetoric or

postwar ideologues.

Equally interesting evidence remains, however, on this question of

black loyalty. In New Orleans, Confederate leaders confronted an

affluent, articulate, and assimilated free black community. The colored

Creoles were in a difficult position when Louisiana left the

Union—a people without a country. The mixed-race "mulatto"

community emphasized community ties and volunteered to "take arms at a

moment's notice and fight shoulder to shoulder with other citizens." A

local unit of "colored men" even enrolled in the state militia.

|

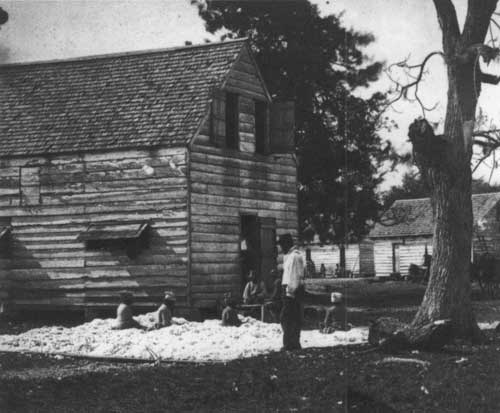

EVEN MORE AFTER SECESSION, THE PRODUCTIVITY OF SOUTHERN PLANTATIONS WAS

DEPENDENT UPON SLAVE LABOR. (LC)

|

|

PRO-UNION HOMESTEADERS WERE DRIVEN OFF THEIR FARMS IN THE MISSOURI

BOOTHEEL BY INVADING CONFEDERATE TROOPS. (FW)

|

|

FUGITIVE SLAVES SOUGHT REFUGE BEHIND UNION LINES AND WERE DUBBED

CONTRABANDS BY FEDERAL OFFICERS UNSURE HOW TO HANDLE THE SITUATION. (LC)

|

African American men who formed companies and offered themselves for

military service, however, were greeted with considerable discomfort by

the new southern government, ignored and spurned. The Confederacy dared

not allow blacks to serve as soldiers. Free blacks who did volunteer

were assigned to projects as teamsters on earthworks projects, building

fortifications, and other menial support roles. The loyalties of these

free blacks volunteers were considerably divided. Most, like the New

Orleans Native Guards, feared that if Confederate independence was

achieved without their help, they might be returned to slavery. To

safeguard status, they pledged themselves to the Confederate cause—perhaps

even aware of the emptiness of such a gesture.

|

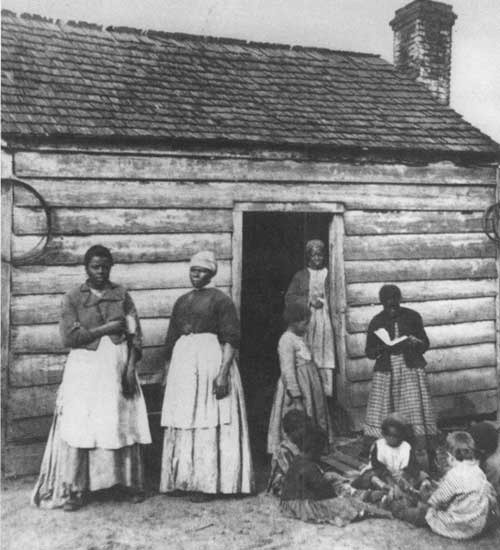

MANY SLAVE CABINS, LIKE THE BIG HOUSE ON THE PLANTATION, WERE

DEPLETED OF THEIR ADULT MALE POPULATION DURING WARTIME. (COLLECTION OF

THE NEW YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

From the very earliest days of the war, slaves were caught in a

vicious thrall. Many hoped to escape bondage and fled behind enemy

lines. The flooding of Union camps with fugitive slaves was an alarming

and unanticipated development for federal officers. Confederates who

claimed that slaves were loyal to owners because the system of

paternalism fostered mutual dependency were repudiated by a steady

stream of black desertions. Unfortunately, federal soldiers expressed

less than sympathetic attitudes toward blacks in bondage, such as the

Union man who balked at the suggestion that he was fighting for blacks'

freedom and retorted: "I ain't fighting for the damned niggers, I'm

fighting for fifteen dollars a month."

Despite such rampant racism among federal troops, African Americans

overwhelmingly sided with the Union—indeed, the Native Guards

proved their true colors during federal occupation. When Union forces

threatened to overrun the Crescent City in the spring of 1862, black

troops volunteered to remain behind. They ended up greeting soldiers in

blue with jubilation and switching sides effortlessly.

From the earliest days of the war, federal military units employing

blacks were organized in South Carolina and Louisiana to capture the

runaways and harness their loyalty. Thousands of African Americans were

willing to take up arms against the Confederacy. The flood of black

volunteers northward from the Confederate states increased dramatically

with the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863. It was a time of

tremendous rejoicing for slaves trapped behind Confederate lines. Most

thought of New Year's Day with sadness, as it was the time when sales

were organized and families separated, nicknamed "Heartbreak Day." But

after 1863 the majority of African Americans would celebrate instead of

dread this date.

The Union at first resisted the use of blacks as soldiers, although

these runaways, who were called contrabands were welcomed and employed

as teamsters and ditchdiggers to man the engineering and quartermasters'

corps. But free blacks persisted and commanders relented, so well over

100,000 black men from Confederate states ran away to join the Union

army. By war's end nearly 200,000 African Americans had served under the

Union flag.

|

AN 1863 ILLUSTRATION OF A MALE SLAVE BEING SEPARATED FROM HIS FAMILY.

(LC)

|

Despite Confederate efforts to stem the tide, the federals were able

to drain plantations of precious manpower and, even more boldly, allow

former slaves to return to these plantations as enemy soldiers—an

alarming prospect for most planter households. As one former slave

soldier reported when he went to see his mistress after the Battle of

Nashville, she upbraided him, reminding him of how she nursed him when

he was sick, and "'now, you are fighting me!' I said, 'No'm, I ain't

fighting you, I'm fighting to get free.'"

Slave women and families, left behind by fathers and husbands, could

be thrown into precarious situations when planters discovered "treason"

and vented their anger on family members who remained in slavery. One

wife left behind in Missouri confided: "They are treating me worse and

worse every day. Our child cries for you. Send me some money as soon as

you can for me and my child are almost naked." A white commander of a

black regiment complained that planters forbade wives and children to

see these black men in blue and prevented all communication, especially

the flow of wages back to the plantation home. Some African American

soldiers, driven to desperation by such treatment, risked all to return

and retrieve families, such as Spottswood Rice, who plotted from his

hospital bed to rescue his children: "Be assured that I will have you if

it cost me my life." One Kentucky woman spirited her several children

away, only to be halted on the road by her master's son-in-law, "who

told me that if I did not go back with him he would shoot me. He drew a

pistol on me as he made this threat. I could offer no resistance as he

constantly kept the pistol pointed at me." Forcing her to return to

slavery at gunpoint, the man kept her seven-year-old as hostage to

ensure that she wouldn't run away again.

The masses of African Americans who joined the Union both

undermined the Confederate cause and strengthened the fight for

emancipation.

|

Black women of the South, like white women, suffered when menfolk

went off to war. Jane Welcome wrote a letter complaining to Lincoln: "I

wont to know sir if you please wether I can have my son relest from the

arme he is all the subport I have now his father is Dead and his brother

was all the help that I had." The president's office replied: "The

interests of the service will not permit that your request be granted."

But evidence also suggests that many black women willingly bade slave

men off to war. Although fearing for soldiers' safety and dreading

repercussions, they saw this occasion as a golden opportunity to secure

future freedom. Only 11 percent of the black population within the

country was free, and the majority of slaves knew military service was a

means of liberation. The masses of African Americans who joined the

Union both undermined the Confederate cause and strengthened the fight

for emancipation. Blacks in the Union armed forces struck a vital blow

to white southern pride, all the while crippling the plantation economy.

In the North, persistence on the part of the free black community

prodded the federal government into accepting black military

potential.

When the war broke out in 1861, the North placed its faith in moral

superiority and material advantage. The Union was a powerful image, and

Lincoln used his "house" metaphor, hoping to keep the national family

together. The Union wanted to impress upon its sibling rival that it

possessed more improved farmland than the South and more soldiers in its

growing population than did the Confederacy. Southern superiority in

exports, almost exclusively cotton, could be abolished with the

blockade. The North had over 125,000 industrial firms and the South had

less than 20,000. New York State alone manufactured four times the value

of manufactured products as did the entire Confederacy. One

county in Connecticut manufactured more firearms than all the

southern states combined.

|

UNION RECRUITS PARADE DOWN BORADWAY IN MANHATTAN, ONLY A

FEW DAYS AFTER LINCOLN'S FIRST CALL TO ARMS. (BL)

|

The North had more and better ports, superior canals, and generally

better transportation. Although the United States boasted one of the

largest railroad networks in the world, less than one third of its

tracks were in the southern states—and 96 percent of American

trains were manufactured in the North. Southern shipbuilding was

considerably inferior to the size and scope of northern naval

capabilities. Financial centers, especially sophisticated trade in

bonds, were concentrated along the northeastern seaboard. Southern

farmers were less commercially acclimated than the New England, Middle

Atlantic, and Old Northwest homesteaders, with closer ties to eastern

markets, fed by flatboat and steamer trade.

|

THE NORTH HAD GREATER INDUSTRIAL AND MANUFACTURING MIGHT AS TYPIFIED BY

THIS NEW ENGLAND FACTORY. (LC)

|

|

CIVILIANS FREQUENTLY DEPENDED UPON GOVERNMENT RATIONS, STAPLE ITEMS

BECAME SCARCE AT LOCAL SHOPS, AND PANTRIES EMPTIED WHEN THE WAR

STRETCHED FROM MONTHS INTO YEARS. (LC)

|

At the same time, most white southern volunteers had been trained in

local militias and were better equipped to forage from their hunting

expertise. Further, the Confederacy declared its independence, which

meant it could conduct a defensive war against Yankee invaders, a far

simpler tactic than the conquest required for Union victory. The numbers

were reputedly against Confederate victory, but the spirit was strong,

and the North had not anticipated just how entrenched and determined

Confederate rebels had become.

|

|