|

THE SOUTHERN HOME FRONT (continued)

|

CONFEDERATE CHILDREN CAUGHT IN THE THROES OF WAR

Carrie Berry was too young to recall events in her home town of

Atlanta when Georgia joined the Confederacy. But by 1864, when she

turned ten, Berry reported the toll the war had taken. On her birthday,

she revealed: "I did not have a cake. Times were too hard, so I

celebrated with ironing. I hope by my next birthday we will have peace

in our land so that I can have a nice dinner." Like those of many young

white girls of the Confederacy, her formerly prosperous parents were

unable to afford peace time luxuries. In 1864 Margaret Junkin Preston of

Virginia was shocked to report in a letter: "G. and H. at Sally White's

birthday party: H. said they had 'white mush' on the table; on inquiry,

I found out it was ice cream! Not having made any ice cream since

wartimes, the child had never seen any, and so called it white

mush."

Emma Le Conte reported in 1865 at the ripe old age of seventeen: "I

have seen little of the lightheartedness and exuberant joy that people

talk about as the natural heritage of youth. It is a hard school to be

bred up in and I often wonder if I will ever have my share of fun and

happiness." Some girls tried to look on the bright side. Amanda

Worthington in rural Mississippi confided: "I think the war is teaching

us some useful lessons—we are learning to dispense with many things

and to manufacture other."

|

ATLANTA CIVILIANS HUDDLE IN A SHELTER DURING A FEDERAL BOMBARDMENT.

(COURTESY OF THE ATLANTA HISTORY CENTER)

|

The war also taught children some terrible lessons. Cornelia Peake

McDonald remembered her three-year-old wailing and clinging to her doll

Fanny, crying that "the Yankees are coming to our house and they will

capture me and Fanny." Another mother recounted a traumatic incident

during Sherman's march. When Union soldiers invaded her home, her

six-year-old daughter hid with her treasures—a bar of soap and her doll.

"One of the men approached the bed, and finding it warm, in a dreadful

language accused us of harboring and concealing a wounded rebel, and he

swore he would have his heart's blood. He stooped to look under the bed,

and seeing the little white figure crouching in a distant corner, caught

her by one rosy little foot and dragged her forth. The child was too

terror-stricken to cry, but clasped her little baby and her soap fast to

her throbbing little heart. The man wrenched both from her and thrust

the little one away with such violence that she fell against the

bed."

Such scenes created vivid memories and tales oft repeated. So

throughout the war, and the years to come, the mere mention of "Yankees"

might strike terror in Confederate children, stimulating fears that

haunted them in darkened bedrooms or around dying campfires.

|

|

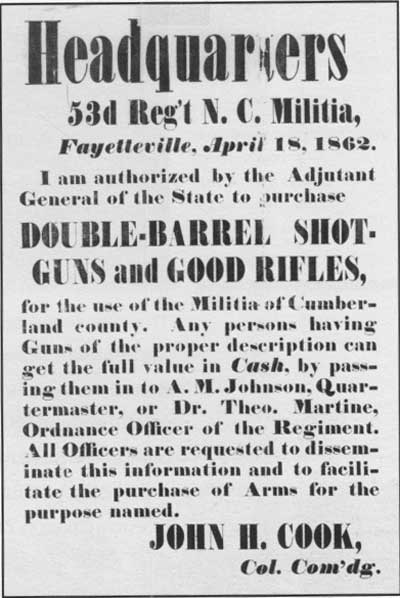

SOUTHERN COMMANDERS HAD TO SEEK WEAPONS FROM CIVILIAN SOURCES TO KEEP

THEIR TROOPS ARMED. (UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA LIBRARY)

|

By 1864, when plantation mistress Clara Bowen was joined by her

husband for a week's furlough, she hoped he would not return to the

front and wrote to a friend: "Do not call me unpatriotic, Alice! I am

sure farmers are as necessary to our suffering country as soldiers. Food

and clothing must be made for the army as well as for the women and

children—starvation would be a more powerful foe than those we are

now contending with." By the time Bowen wrote from Ashtabula, South

Carolina, southern agriculture was already in ruins.

African American labor was being spirited away for the Union

cause—men as soldiers and women as cooks and laundresses. African

Americans also served as nurses in government hospitals, drivers of

supply wagons and ambulances, and cooks and valets within Confederate

camps—all slaves donated or supervised by masters. Most

important, the War Department could and often did have the authority to

impress slave labor into service. Louisa McCord Smythe recalled that her

family slaves were requisitioned in wartime Carolina.

Slaves remained at the root of the problem during the prolonged

battle for southern independence. Only in the last few weeks of the war

was the Confederate government willing to consider arming blacks in a

desperate bid to continue the losing battle. But by as early as 1863 the

floodgates of freedom had opened wide to African Americans who seized

the opportunity to escape masters. This disintegrating process

undermined the resolve of Confederates, especially non-slave owners who

formed the majority of the fighting force. For those left behind on

plantations, the process was even more painful to witness, as the spirit

of emancipation created not so much a tidal wave of resistance as a

strong and constant flow that washed over the South, eroding

slaveholders' power with the sands of time, day by day.

|

EMANCIPATED AFRICAN AMERICANS WORKING AS FREE LABOR IN THE FIELDS OF

SOUTH CAROLINA. (WESTERN RESERVE HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

|

WINCHESTER, VIRGINIA—A TOWN THAT CHANGED HANDS FIFTY-TWO TIMES

DURING THE WAR. (USAMHI)

|

|

WITHOUT SLAVES, MANY SOUTHERN FIELDS AND PLANTATIONS WENT UNTENDED. (LC)

|

The weakening of the Confederacy was most visible in those areas of

the occupied South where escaped slaves, contrabands settled with

families and expropriated Confederate lands, with the blessings of the

federal government which leased property to blacks. On the South

Carolina Sea Islands, a thriving community was established, what

historian Willie Lee Rose has called a "rehearsal for Reconstruction."

When federals conquered and secured the region in 1862, a community of

ten thousand blacks were left behind. Many northern teachers moved in,

including a young woman born into a prominent free black family in

Philadelphia, Charlotte Forten. Forten had been educated in Salem,

Massachusetts, and become a teacher herself. She felt excited by the

challenge of traveling south to help the freedpeople and settled in at

St. Helena Island, the lone black among the colony of northern teachers.

In May 1864 the Atlantic Monthly published a two-part article

chronicling her experiment, "Life on the Sea Islands," which provides a

vivid record of this dramatic episode. She found exceptional pupils: "I

wish some of those persons at the North who say the race is hopelessly

and naturally inferior could see the readiness with which these

children, so long oppressed and deprived of every privilege, learn and

understand." As this experiment proved successful, federal authorities

sold some of the sea island property to blacks during auctions for

unpaid taxes.

Another successful experiment was conducted at Davis Bend,

Mississippi, on land owned by the family of the Confederate president.

When Jefferson Davis's brother was forced to abandon his plantation in

1862, he was unable to convince his slaves to accompany him, and when

Union troops arrived, blacks had both expropriated the Big House and

managed to run the place efficiently. By 1865 these self-sufficient

African Americans turned the place into what General Grant called "a

negro paradise."

|

"CONTRABANDS" SELF-LIBERATED SLAVES FOLLOWING POPE'S TROOPS. (LC)

|

Many women expressed complex sentiments in the wake of this

development, like the insightful Mary Chesnut, who commented on a slave

insurrection: "I have never thought of being afraid of negroes. I had

never injured any of them; why should they want to hurt me?" After her

cousin was strangled by slaves on a nearby plantation, she further

claimed: "But nobody is afraid of their own negroes. These [her cousin's

murderers] are horrid brutes—savages, monsters—but I find

everyone, like myself, ready to trust their own yard." Plantation women

were trained to repress all fears of slaves, to maintain the pretense

that enslaved African Americans were happy, childlike creatures.

Desertion of plantations by slaves was an integral part of wartime,

and, ironically, as one woman complained, "those we loved best, and who

loved us best—as we thought—were the first to leave."

Seventeen slaves fled the Wickham plantation in Hanover County,

Virginia, in June 1862 and another seventeen were "carried off" between

June 26 and July 5, 1863. Over 250 slaves remained behind, but Wickham

believed this loss a considerable blow. Slaves fleeing behind enemy

lines did not just represent a loss of income but equally a loss of

face.

Why were African Americans so anxious to escape slavery if it was the

pleasant paternalistic system owners painted it? Confederates again and

again portrayed scenes of slave loyalty to defend themselves against

Yankee charges. Eyewitness southern accounts provide occasional

refutation of these tender scenes. Belle Edmondson described rounding up

runaways in Shelby County, Tennessee: "A family of negroes had got this

far on their journey from Hernando to Memphis when Mr. Brent met them,

and they ordered him to surrender to a Negro, he fired five times, being

all the loads he had—killed one Negro, wounded another, he ran in

the woods and we saw nothing more of him—one of the women and a

little boy succeeded in getting off also." For the first time since the

American Revolution, large numbers of women and children found freedom

by deserting behind enemy lines. One mistress complained that slaves "in

some cases have left the plantations in a perfect stampede."

A Union provost marshal reported in March 1864: "The wife of a

colored recruit came into my Office tonight and says she has been

severely beaten and driven from home by her master and owner. She has a

child some two years old with her, and says she left two larger ones at

home." Wives left to manage with depleting resources and a recalcitrant

labor force took out their frustrations on remaining slaves. Emma Le

Conte complained: "The field negroes are in a dreadful state; they will

not work, but either roam the country, or sit in their houses . . . I do

not see how we are to live in this country without rule or

regulation."

|

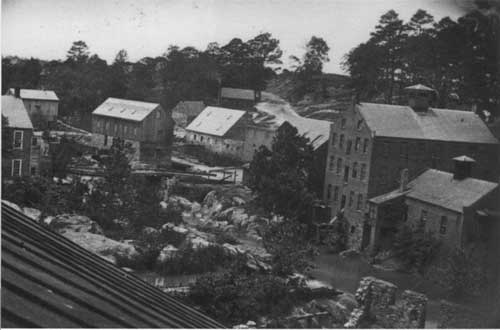

A COTTON MILL IN PETERSBURG, VIRGINIA. (LC)

|

The lack of food and material comforts became so severe that some

planters, to conserve supplies, simply turned slaves off the land. Mary

Stribling reported that by the time of Lincoln's Emancipation

Proclamation, her father had already warned slave women and children he

would resort to selling those who could not earn their own keep. Much of

the scarcity was a product of contributing to the Confederate cause, as

one Mississippi mistress explained: "My heart has yearned over our

brave, noble, bare-footed ragged young men, & have done all I could

in my limited way to meet their necessities. Our stock of cloth laid up

for the negroes is almost exhausted, having given suits of clothes to

the soldiers. We also have given hundreds of pairs of socks, the amount

of 500, I think to the Army. Some three or four weeks since we sent

twelve blankets, eight dozen pairs of socks, three carpet blankets, to

Genl. Prices Army."

Besides the endless shipping of supplies, plantations were expected

to host Confederate soldiers. Many gave generously to the anonymous sons

of the Confederacy who imposed on their hospitality. Rebecca Ridley

lived in the cook-house of her former plantation Fair Mont, outside

Murfeesborough, Tennessee, after Yankees burned her home. Following a

battle she reported: "The ground has been covered with snow and

ice—freezing our poor unprotected soldiers . . . poor fellows, how

my heart bleeds for them. They come in at the houses to warm, and get

something to eat, and some of our citizens who pretend to be very

Southern grudge them the food they eat—say they will be eat

out."

The burdens of contact with Yankees were unbearable to most southern

white women. Cordelia Scales, on her plantation eight miles north of

Holly Springs, Mississippi, reported a visit from the Kansas Jayhawkers:

"They tore the ear rings out of ladies ears, pulled their rings &

breast pins off, took them by the hair; threw them down & knocked

them about. One of them sent me word that they shot ladies as well as

men & if I did not stop talking to them so & displaying my

confederate flag, he'd blow my brains out." Amanda Worthington, also on

a Mississippi plantation, told of the 20,000 bales of government cotton

that went up in flames with over a thousand head of cattle and a

thousand head of hogs and ten thousand bushels of corn lost to pillaging

Yankees.

|

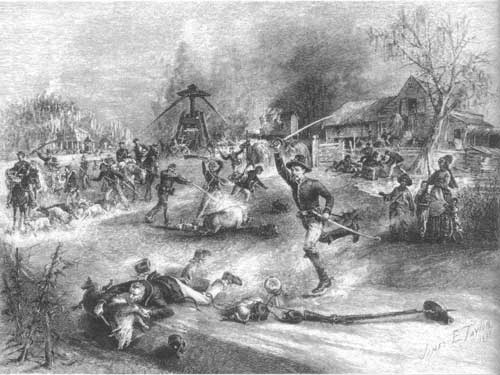

YANKEE TROOPS FORAGING ON A GEORGIA FARM. (BL)

|

|

A SOUTHERN ARTIST CAPTURED A SCENE FREQUENTLY REPORTED IN MEMOIRS OF

YANKEE SOLDIERS TERRORIZING SOUTHERN CIVILIANS. (LC)

|

Sarah Huff, in northern Georgia, remembered that the "Yankees

stripped us bare of everything to eat; drove off all the cattle, mules,

horses; killed chickens; and turned their horses into a wheat field so

that what the horses could not eat was destroyed by trampling." Dolly

Lunt recalled a similar siege at her home near Covington, Georgia: "But

like demons they rush in! My yards are full. To my smoke house, my

dairy, pantry, kitchen, and cellar, like famished wolves they come,

breaking locks and whatever is in their way." Mary Stribling in Fort

Royal, Virginia, was appalled at Yankee conduct: "They came into the

house and searched it several times and stole various articles of female

apparel for which it is impossible to imagine what purpose they could

use them . . . they threatened the girls with the worst treatment. They

wrote all over the walls addressing the ladies as if they were writing a

letter, they write low pieces of obscenity to which they signed Jeff

Davis's name."

Some plantation houses in South Carolina and other regions proudly

display Yankee graffiti today to preserve the defilement of their homes

by soldiers who clearly weren't "gentlemen." Graffiti was a small

problem compared to shelling. Further, arson was an awful crime which

too many women witnessed. The savagery of this torching policy prompted

Henrietta Lee to write directly to Union commander, General David

Hunter:

"Yesterday your underling, Captain Martindale, of the First New York

Cavalry, executed your infamous order and burned my house . . . the

dwelling and every outbuilding, seven in number, with their contents

being burned, I, therefore, a helpless woman whom you have cruelly

wronged, address you, a Major General of the United States Army, and

demand why this was done . . . . Hyena-like, you have torn my heart to

pieces! For all hallowed memories clustered around that homestead; and

demonlike, you have done it without even the pretext of revenge . . . .

Your name will stand on history's pages as the Hunter of weak women, and

innocent children: the Hunter to destroy defenseless villages and

beautiful homes—to torture afresh the agonized hearts of

widows."

But not all contact with Yankees was as brutal and hellish. Sallie

Moore, a Virginian, reported that when a Union officer was inspecting a

woman's home when climbing up the stairs "suddenly a string broke and a

shower of spoons and forks came raining down the steps from under her

hoops." In this tense moment, the soldier gallantly stooped to help the

woman retrieve her silver, which he returned to her.

The testimony of southern blacks provides a powerful counterpoint to

Confederate memoirs, as former slave Eliza Sparks of Virginia confided

with special poignancy an encounter with a Yankee:

"I was nursin' my baby when I heard a gallopin', an' fo' I coud move

here come de Yankees ridin' up . . . . The officer mought of been a

general—he snap off his hat an bow low tome an' ast me ef diswas de

way to Gloucester Ferry Den he lean't over an' patted de baby on de haid

an' ast what was its name. I told him it was Charlie, like his father,

Den he ast, 'Charlie what' an' I told him Charlie sparks. Den he reach

in his pocket an' pull out a copper an' say, 'Well, you sure have a

purty baby. Buy him something with this; an' thankee fo' de direction.

Goodbye, Mrs. Sparks.' Now what you think of dat? Dey all call me 'Mrs.

Sparks!'"

The slave presence was a trouble some issue for Confederate

civilians. African Americans were both potential enemies as well as

desperate allies within the plantation South. White women ironically

might despair both over slaves running away and over slaves remaining

behind to be looked after during federal invasion.

In the rich plantation region along the Combahee River in South

Carolina, Union commander David Hunter, assisted by the intrepid scout

and spy Harriet Tubman, recruited over 800 black soldiers during summer

raids in 1863. By rousting slaves from their owners, spreading fear and

mayhem in this and other successful operations, the North was able to

wreak havoc with the plantation system—most effectively in the

Mississippi Valley during the fall of 1863, when nearly 20,000 slaves

deserted masters to join the Union army.

These forms of open rebellion were not as common as daily resistance.

The enemies within came to represent as much of a threat to plantation

productivity as invading foes. White southerners failed to grasp this

reality until very late in the war. Indeed, by the time the tide had

turned, some masters were forced to encourage slaves to run

off—deprived of any means of feeding a dwindling work force.

Especially in the battle-torn Virginia countryside, planters might

record the number of runaways on a daily basis while northern troops

crisscrossed the country.

|

BURIAL OF LATANÉ BY WILLIAM WASHINGTON (1864). WHEN THIS

PAINTING WAS FIRST PUT ON DISPLAY, VIEWERS IN RICHMOND DROPPED COINS IN

A BUCKET PLACED IN FRONT OF IT. TOUCHED BY THE THEME OF SACRIFICE. (MC)

|

|

ESCAPING CHARLESTON WITH THE THREAT OF UNION OCCUPATION. (LC)

|

|

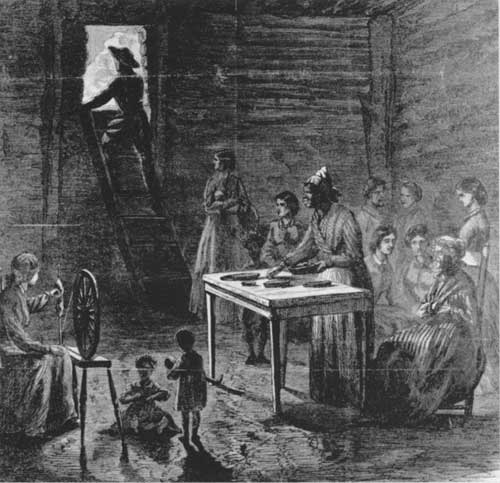

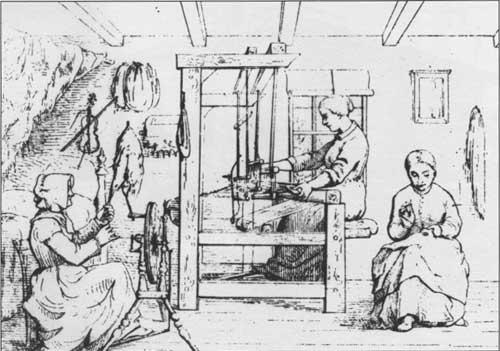

SOUTHERN HOMEMAKERS MANUFACTURING CLOTHING. (LC)

|

Many black youth on plantations initially found the whole idea of war

exotic and intriguing. Rachel Harris recalled, "I went with the white

chillun and watched the soldiers marchin'. The drums was playing and the

next thing I heerd, the war was gwine on. You could hear the guns just

as plain. The soldiers went by just in droves from soon of a mornin'

till sun down." But soon, the depletion of adult labor increased the

burdens on slave children. Henry Nelson, only ten years old when the war

broke out, remembered, "You know chillun them days, they made em do a

man's work." Eliza Scantling, fifteen in 1865, remembered she "plowed a

mule an' a wild un at dat. Sometimes me hands get so cold I jes'

cry."

For slave children the prospect of an invading enemy was confusing

and, at times, terrifying.

|

For slave children the prospect of an invading enemy was confusing

and, at times, terrifying. One slave remembered being told by the

overseer when the slave was only ten years old that Yankees had "just

one eye and dat right in de middle of the breast." Mittie Freeman, also

ten, hid in a tree when the first bluecoats arrived. There is ample

evidence to demonstrate that black children overcame apprehensions and

even became enamored of Union soldiers in many instances. Although they

might empathize with the adults' sense of jubilation over impending

freedom, at the same time they were children, overwhelmed and frightened

by the prospect of any change. Additionally, carnage was close at hand,

and many slave children witnessed frightening results. James Goings,

only three when war broke out, recalled that by the end of the war "it

wuzn't nuthin' to fin' a dead man in de woods."

|

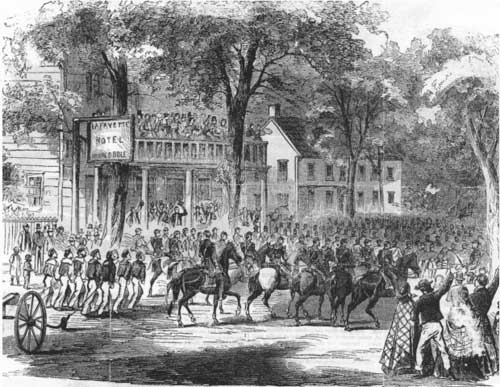

IN TOWNS LARGE AND SMALL THROUGHOUT THE SOUTH. CITIZENS WOULD PROUDLY

CHEER FOR THEIR BOYS MARCHING OFF TO WAR. (HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

|

AN ATLANTA MANSION, SCARRED BY SHELLING. (LC)

|

Many black children sacrificed parents as well to the terrible

conflict. As slave men fled the plantations, leaving wives and children

behind, thousands were fatherless and hundreds were orphaned. Amie

Lumpkin of South Carolina recalled her wartime loss: "My daddy go 'way

to de war 'bout distime, and my mammy and me stay in our cabin alone.

She cry and wonder where he be, if he is well or he be killed, and one

day we hear he is dead. My mammy, too, pass in a short time." Slave

children made their unwilling offerings, too.

The southern cult of sacrifice began on a rather high note of

camaraderie and fellowship within the Confederacy. Parthenia Hague

described the way women in the Alabama countryside would gather for

spinning bees: "sometimes as many as six or eight wheels would be

whirring at the same time." Hague was heartened by these efforts, but

another confided, "Slowly but surely the South was 'bled white.'

Luxuries, there were none." The search for necessities preoccupied most

southern housewives, and one girl in Winchester complained: "Out shopping

all morning. I'd give a cent if Jennie Baker would quit sending for

me to buy things for her. Its the bane of my existence for every store

here in town is bare and nothing you want in there. Here today I walked

all over town and couldn't get anything I wanted."

Pooling resources was a game that may have been a festive ritual

early in the war, but by 1862 scarcity was worrisome, and by the summer

of 1863 inflation and rationing made putting food on the table a major

ordeal. Lucy Johnston Ambler fretted in summer 1863: "Indeed everything

looks very gloomy. From having a comfortable table, I am reduced to

bacon bone . . . I have a very sick grandchild and several servants sick

with no suitable medicine." These stories were kept from menfolk away at

war.

|

A NORTHERN ARTISTS STARK IMAGE OF THE RICHMOND BREAD RIOT. (FL)

|

Women's sacrificial courage was summarized by Louisa McCord Smythe:

"We would have died before we would complain to a man in the army. They

had enough to bear without that." But after several seasons of war, no

amount of sanitation could prevent soldiers from knowing the dire

straits on the Confederate home front.

The constant cry for salt and bread echoed from the banks of the

Shenandoah to the Delta and boomeranged back to the Confederate capital.

A woman in Richmond wrote to a friend on April 4, 1863, in the wake of

civil disturbances. She repeated the words of a young girl: "We are

starving. As soon as enough of us get together we are going to the

bakeries and each of us will take a loaf of bread. That is little enough

for the government to give us after it has taken all our men." Nearly a

thousand women and children banded together and "marched along silently

and in order." They methodically emptied stores of goods and refused to

stop even when the mayor confronted them to "read the Riot Act." The mob

even ignored the city battalion. In desperation, Jefferson Davis

appeared. The Confederate president was at first greeted with hisses,

"but after he had spoken some little time with great kindness and

sympathy, the women quietly moved on, taking their food with them." But

over forty-eight hours later, an observer reported, "Women and children

are still standing in the streets, demanding food, and the government is

issuing to them rations of rice."

All of northern Virginia was alarmed by the Richmond Bread Riot and

spread the word. One woman confided, "I am telling you of it because

not one word has been said in the newspapers about it." People

throughout the countryside certainly understood the impulse. Virginia

Cloud of Fort Royal complained, "I do not think the speculative spirit,

so prevalent, is at all patriotic. I fear there are many who love

mammon more than their country." There is evidence of widespread

scapegoating during this period, and Jewish merchants in the Confederate

capital were targeted by unhappy civilians. Government censorship

suppressed news of such disturbances, but these incidents erupted

spontaneously throughout the South.

Feeding the Confederacy and keeping the economy going was an

increasingly impossible task. Women were reduced to dreams and wishes.

Without food, without money, many women were perilously close to the

abyss. Sarah Rice Pryor, a refugee outside Petersburg, gave birth during

a blizzard over Christmas 1863. Mother and newborn were still bedridden

three months later when her husband sought her out and found his wife

and three children abandoned by the maid and being cared for by a hired

hand. The furloughed soldier, in shock at the crumbling state of

affairs, sold goods to raise cash to care for his wife. It was his

desire that she never "again fall into the sad plight in which he had

found me."

From the war's opening hours on through to the end, Confederates

employed dramatic religious rhetoric. A girl wrote to her cousin from

South Carolina: "This is indeed a terrible war. How many hearts have

been made desolate by its ravages. How many vacant places around the

family altars. How terrible is the wrath of God, our sins as a people

has brought this upon us and we should humble ourselves before Him. I

believe that Genl. Jackson was taken from us because we were making a

god of him, not for any sin or unrighteousness in him, for I believe

that he was not only doing good work as a soldier of our Confederacy but

also of the cross." Jackson was indeed worshiped and revered during his

military career. After death, he became a martyr and after the war

canonized as part of the Confederate trinity: Davis, Lee, and

Jackson.

|

A BOMBED-OUT CHURCH IN DOWNTOWN CHARLESTON. (LC)

|

Christian faith gave these women their redemption as well. They

struggled mightily to find some sense of the slaughter, to the endless

drumbeat of defeat. Eliza Andrews, after a visit to Andersonville

Prison, worried about vengeance: "I am afraid that God will suffer some

terrible retribution to fall upon us for letting such things happen. If

Yankees ever should come to South-West, Ga . . . and see the graves

there, god have mercy on the land." This prophecy of doom perhaps came

true in the form of William T. Sherman. Almost all white southerners

recast Sherman's March as God's test of their faith. When Sherman's

troops set off from Atlanta to Savannah, his men began in an orderly

fashion, especially the first ten days, covering 275 miles. But after

they reached Camp Lawton, a prisoner of war camp at Millen, many of the

lawless brutalities emerged which made this campaign infamous.

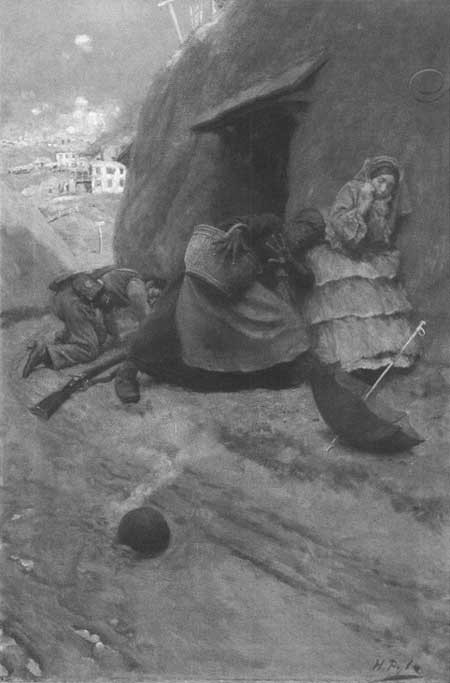

Another severe test of faith came for many Confederates during the

prolonged campaign to control Vicksburg, when thousands were caught up

in the battle over this key port. This linchpin city on a bluff

overlooking the Mississippi River had been the focus of federal military

strategy for months. Union General Ulysses S. Grant finally gathered

70,000 to assault the CSA force of 28,000 in the summer of 1863. Before

surrender, the besieged Confederates would be reduced to eating horses,

dogs, and rats. The bombardment was so fierce that civilians dug caves

into the mountainside for shelter. The memoir of Mary Ann Loughborough

documented the genuine hardships of civilians. Loughborough recalled an

incident when a shell lobbed into the center of a cave, crowded with

families: "Our eyes were fastened upon it, while we expected every

moment the terrific explosion would ensue. I pressed my child closer to

my heart and drew nearer to the wall. Our fate seemed almost certain;

and thus we remained for a moment with our eyes fixed in terror on the

missile of death, when George, the servant boy rushed forward, seized

the shell, and threw it into the street, running swiftly in the opposite

direction." Both George and the cave dwellers escaped injury.

|

TERROR IN THE GEORGIA COUNTRYSIDE AT THE APPROACH OF UNION GENERAL

WILLIAM T. SHERMAN. (LC)

|

|

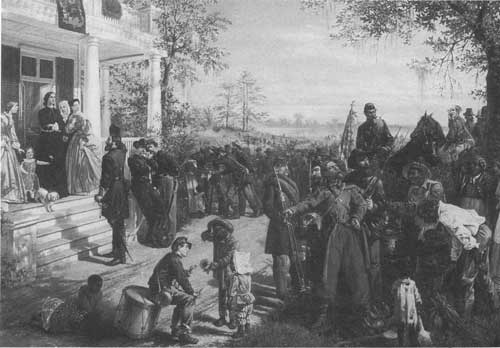

SHERMAN'S MARCH TO ATLANTA BY THOMAS NAST. THIS PAINTING DEPICTS

SLAVES GREETING FEDERAL SOLDIERS WHILE THE PLANTATION OWNERS LOOK ON

DISAPPROVINGLY. (COURTESY OF SOTHEBY'S)

|

Nerves frayed, supplies disappeared, and the determined Yanks

maintained their attack. Scurvy, mule-skinning, and bombardment chipped

away at morale. Wounded animals limped around looking for grass, evading

butchers. Nightly shelling kept frightened children awake. The

challenges were tremendous and daily life was precarious at best and,

upon occasion, deadly.

Loughborough recalled a particularly awful day when one of the young

girls, bored by confinement, ventured out: "On returning, an explosion

sounded near her—one wild scream and she ran into her mother's

presence, sinking like a wounded dove, the life blood flowing over the

light summer dress in crimson ripples from a death wound in her side

caused by the shell fragment. A fragment had also struck and broke the

arm of a little boy playing near the mouth of his mother's cave." She

recalled the frequency of heartwrenching "moans of a mother for her dead

child."

After countless dead, the Confederates hoisted the white flag on July

4, 1863. The soldiers were placated by the dignity they were accorded. As

the half-dead men stacked their arms, witnesses detected a note of

sympathy from their Union conquerors. The treaty, concluded on a federal

holiday, contained generous terms and nearly all soldiers were

paroled.

|

LIFE IN VICKSBURG

Mary Jane Sitterman was visiting her quartermaster husband in

Vicksburg when she got trapped by the advancing Union army closing in on

Vicksburg from the east. She became a cave dweller during the siege and

left the following account:

"We ... fitted the cave with the articles of housekeeping and were

comfortably fixed. Our beds were arranged upon planks that were elevated

on improvised stands, planks covered the ground floor, and these in turn

were covered with matting and carpets. The walls surrounding the beds

were also covered with strips of carpets, so all possible dampness was

by a little care entirely eliminated. The wall carpeting was made

adherent by small wooden pins or stobs."

Gordon Cotton, director of the Old Courthouse Museum in Vicksburg,

relates the following in his Vicksburg: Southern Stories of the

Siege (Vicksburg, 1988):

"Dora Miller noted that dogs and cats virtually disappeared from the

streets and wondered where they went. In The Daily Citizen,

Editor J. M. Swords described a dinner for eight shared by friends 'a

delicious and featured rabbit' stew. He also pointedly mentioned that

the cats had simultaneously disappeared and declared the felines of the

city were an endangered species."

—Michael Ballard

|

THE SHELL BY HOWARD PYLE, 1908 (MR. AND MRS. HOWARD P. BROKAW,

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF THE BRANDYWINE RIVER MUSEUM)

|

|

The defeat at Vicksburg and almost simultaneous Union victory at

Gettysburg (with 15,000 casualties out of the 60,000 rebels engaged)

seemed a dress rehearsal for the final surrender in April 1865. Many

women by this fateful time sensed the doom on the horizon and began,

consciously or unconsciously, to contemplate surrender. They continued

to consolidate their own position as women worthy of Greek tragedy;

indeed, one woman writer composed such a narrative with her novel:

Augusta Jane Evans's Macaria; or Altars of Sacrifice (1864). From

this turning point in July 1863 to the treaty at Appomattox, hundreds of

thousands were refugees, hundreds of thousands were

wounded, and tens of thousands were buried. As they hoped and prayed for

the final battle, few could contemplate life beyond war's end, afraid to

anticipate the outcome.

|

|