|

THE SOUTHERN HOME FRONT

The willingness of the planter class to donate all, including loved

ones and family members, to the Confederate cause has become a part of

Civil War folklore. Indeed, there are many examples of aristocratic

parents—those who could well have afforded to pay for

substitutes—coaxing sons to war. Evidence abounds that southern

patriotism and a sense of honor spurred the wealthy elite into action.

Equally poignant, many families were devastated by the painful divides

the war provoked. Septima M. Collis reported in her memoir: "I never

fully realized the fratricidal character of the conflict until I lost my

idolized brother Dave of the Southern army one day, and was nursing my

Northern husband back to life the next."

|

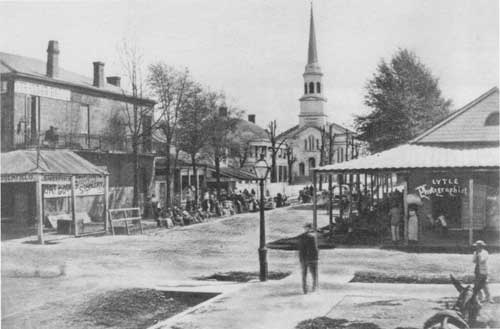

CITIZENS GATHER AT THE HANOVER JUNCTION RAILROAD STATION AND WAIT FOR

NEWS OF THE BATTLE. (LC)

|

Despite the threat of divided loyalty, Confederate nationalism

prevailed and rabid chauvinism flourished among the landed gentry. One

Selma belle broke her engagement because her fiance did not enlist

before their proposed wedding day. Support for the rebellion created a

strange mix of symbols and images for southern whites. Confederate

manhood demanded prolonged separation from the glorified household and,

ironically, absence from those very loved ones men pledged to protect.

But by individual forfeit, all households might be protected, so private

gain was sacrificed to the collective good.

|

RECRUITING IN THE SHENANDOAH VALLEY FOR

ENLISTMENT IN THE CONFEDERATE AMRY. (FW)

|

The South nurtured extremity and zeal, encouraging the press to

promote stories of female vigilance. The Raleigh Register

reported an incident in September 1863: "A young lady was engaged to be

married to a soldier in the army. The soldier suddenly returned home.

'Why have you left the army?' she inquired of him. 'I have found a

substitute,' he replied. 'Well, sir, I can follow your example, and

find a substitute, too. Good Morning.' And she left him in the middle of

the room, a disgraced soldier." Women might be sentimental, but they

could not let fears and personal concerns interfere with the Confederate

cause. The weight of victory rested heavily on the plantation matrons'

shoulders.

Virginian Margaret Junkin Preston described her husband's letters

home: "Such pictures of horrors as Mr. P. gives! Unnumbered dead Federal

soldiers cover the battle field, one hundred in one gully, uncovered and

rotting in the sun, they were all strewn along the roadside. And dead

horses everywhere by the hundred. Hospitals crowded to excess and loath

some beyond expression in many instances. How fearful is war! I cannot

put down the details he gave me, they are too horrible,"

|

EQUIPMENT BY W. L. SHEPPARD. DEPICTION OF THE ELABORATE

PREPARATIONS MADE FOR DEPARTURE INTO THE CONFEDERATE ARMY. (MC)

|

Mothers and wives, despite melancholy, rose to the occasion. In

Montgomery, Alabama, southern matrons formed a Ladies Hospital

Association in the early months of 1862. Sophia Gilmer Bibb, an

industrious widow, organized women of the town to donate supplies, staff

a hospital, and remain on call to take care of wounded soldiers and

prisoners. Women in Columbia, South Carolina, transformed the state

fairgrounds into a hospital, and the state college in town soon became a

medical facility as well. One of the most famous Confederate nurses,

Sally Tompkins, left her family plantation, Poplar Grove, to run a

hospital in Richmond. Twenty-eight and unmarried when the war broke out,

Tompkins was a devoted patriot. Her administration of the Robertson

Hospital won her Confederate fans, including Jefferson Davis, who

awarded her a military commission as "captain." Tompkins accepted her

rank but refused a salary. Phoebe Pember, a socially prominent Jewish

widow, superintended Chirimborazo Hospital in Richmond. Juliet Hopkins,

wife of the chief justice of Alabama, performed such feats that she

became known as the "Angel of the Confederacy." Wounded on the

battlefield in May 1862, she spent the rest of her life with a limp from

her wartime injury.

|

THE RETREAT INTO RICHMOND FROM THE BATTLEFIELD AT SEVEN PINES.

(BL)

|

|

SABRES AND ROSES BY DALE GALLON SHOWS J. E. B. STUART (2ND FROM

LEFT) AND TROOPS SAYING FAREWELL TO SOUTHERN CITIZENS BEFORE EMBARKING

FOR BATTLE. (COURTESY DALE GALLON HISTORICAL ART, GETTYSBURG, PA)

|

Many genteel women were exposed to scenes of ghastly horror when they

went into hospital service. Kate Cumming of Mobile described a typical

scene in April 1862: "The men are lying all over the house on their

blankets, just as they were brought from the battlefield. They are in

the hall, on the gallery, and crowded into very small rooms. The foul

air from this mass of human beings at first made me giddy and sick, but

I soon got over it. We have to walk, and when we give the men anything,

kneel in blood and water." Ladies braced themselves as they marched off

to do their patriotic duties but still reeled from their exposure to

such harsh, taxing conditions.

Wealthy men were expected to make even more dramatic sacrifices as

they donned uniforms to counter the stereotype of a "rich man's war,

poor man's fight." Several units demonstrated the patriotic loyalty of

the planter class, such as the Magnolia Cadets in Selma, Alabama, manned

entirely by local gentry. The privileged elite argued that class lines

blurred during this time of crisis. As one Alabama woman described, "We

were drawn together in a closer union, a tenderer feeling of humanity

linking us all together, both rich and poor."

While white men marched off to war, white families and slaves were

expected to keep the plantation fires tended. Indeed, the planting of

crops was considered a civilian priority, the backbone of Confederate

strategy. Women and slaves were enlisted in this effort to make the

blockaded nation economically self-sufficient. Slave owners and small

farmers alike were warned to "plant corn and be free or plant cotton and

be whipped."

With the onset of war, planters curbed their cotton production,

cutting output in half between 1861 and 1862. Sugar planters, indigo

planters, and other producers of cash crops were encouraged to curtail

production in favor of raising foodstuffs. However, a small group of

planters, who wanted to keep slaves profitable, were willing to trade

with shady speculators and continued to warehouse and smuggle large

cotton crops. Some, like Mississippian James Alcorn, saw the war as a

boom time: "I can in five years make a larger fortune than ever; I know

how to do it and will do it." Alcorn indeed made a killing in

cotton.

Trying to keep slaves in order, trying to conduct agricultural and

commercial activities during wartime disruption, absorbed the entire

planter class. It is safe to say that on the home front, planters faced

a long, slow defeat, like water on a rock, steadily wearing away.

|

SOUTHERN CITIZENS OUTSIDE THEIR HOME ON CEDAR MOUNTAIN, VIRGINIA. (LC)

|

The war turned power relations upside down on the home front. Kate

McClure, a plantation mistress left behind in Union County, South

Carolina, tired of the incompetence of her husband's overseer, Maybery,

while McClure was away at war. She fired the hapless Maybery and

deputized a slave, Jeff, to manage the work force. Indeed, the war

offered many women the opportunity to exert more influence over

plantation affairs, a challenge that many failed to embrace

enthusiastically. They might gain some satisfaction from a job well

done, but most mistresses were preoccupied with the dire straits of the

southern wartime economy. Few escaped the melancholy dread of losing one

or more family members to war.

Most southern plantation mistresses were trained to manage the

planting operations. As the wives of wealthy men who served on the bench

and in the legislature, they endured husbands' frequent and lengthy

absences. The war, however, presented a different dilemma to mistresses

left behind. Now they were faced with the possibility that their loved

ones might not return—something rare in peacetime but all too

common in war. Additionally, the threat of northern invasion undermined

slave owners' authority, and most women found themselves not worried

about prosperity but about survival as the war wore on. This crisis

weighed heavily on planter wives, increasing their burdens as defeat

seemed more and more inevitable.

The popular press advised ladies to elevate the sagging spirits of

menfolk by throwing themselves into good works to help the Confederacy.

Young girls buoyantly welcomed the challenge.

|

The popular press advised ladies to elevate the sagging spirits of

menfolk by throwing themselves into good works to help the Confederacy.

Young girls buoyantly welcomed the challenge. Judith McGuire confessed:

"Almost every girl plaits her own hat, and that of her father, brother,

and lover, if she has the bad taste to have a lover out of the army,

which no girl of spirit would do unless he is incapacitated by sickness

or wounds." Such rhetoric exalted and enforced Confederate fervor, while

stomping out dissent.

Wives and mothers, becoming more and more aware of the sacrifice such

campaigns entailed, responded in time with misgivings to the call to

arms. Alabama bride Mary Williamson cried over her husband's departure

to the army: "This great sorrow makes me forget I ever had such a

feeling as patriotism." Confederate ladies refrained from any public

displays that might be interpreted as disloyalty. The wife of the most

revered soldier within the South, Mrs. Robert E. Lee, confided in a

letter to her child: "The prospects before us are sad indeed as I think

both parties are wrong in this fratricidal war." Whatever feelings she

had in private, Mrs. Lee conveyed total support of her husband, as a

friend commented: "I never saw her more cheerful, and she seems to have

no doubt of our success." This split between the public and private

aspects of women's feelings was prevalent among women of the planter

class.

Confederates celebrated the ethic of self-sacrifice, like the matron

who proclaimed, "We are ready to do away with all forms of work and wait

on ourselves." But as hard times intensified, such sentiments withered.

Many found it difficult to face the impossible dilemmas wartime

presented. One woman confessed to her diary: "The real sorrows of war,

like those of drunkenness, always fall most heavily upon women. They may

not bear arms. They may not even share the triumphs which compensate

their brethren for toil and suffering and danger. They must sit still

and endure." Too few had the luxury of merely sitting still.

Desperate times produced desperate measures. Sallie Brock, the wife

of a Confederate soldier, "was forced to go out into the woods nearby

and with my two little boys pick up fagots to cook the scanty food left

to me." Women reported giving up blankets and even cutting up carpets to

send to the army for soldiers to sleep on. Patriot Katie Miller

reported, "I told ma when provisions got so low that she couldn't

feed a passing soldier to let me know every time one comes and I would

go minus one meal for him."

Wartime papers were filled with ideas about women's sacrifice and

heroism. One patriot in Mobile urged fellow Confederates to donate

family jewels and silver. Another Alabama woman, the niece of James

Madison, advised women to sell their hair to European wigmakers and

donate profits to the government. A bounty of $2 million would be won if

all would chop off two braids apiece at the going rate. She demanded:

"Let every patriot woman's head be shingled!" Wartime hair styles

reveal that few heeded her call.

Southern plantations, which had been concerned with conspicuous

consumption before the war, switched dramatically into plants for

production—and in the case of luxury items, centers for clever

reproduction: persimmons for dates, raspberry leaves for tea leaves,

okra seeds for coffee beans, cottonseed oil for kerosene and beeswax for

candlewax. Many mistresses took to the woods, and one memoirist recalled

that the forest became "our drug stores."

|

THIS PAINTING OF THE 1ST TEXAS CHARGING AT GETTYSBURG SYMBOLIZES THE

SACRIFICE OF CITIZENS FOR THE WAR EFFORT. THEIR FLAG WAS MADE FROM A

WEDDING DRESS. (COURTESY DALE GALLON HISTORICAL ART, GETTYSBURG, PA)

|

The search for necessities preoccupied most Confederate housewives,

and letters are filled with complaints and advice concerning quinine,

food, and other valuables. Pooling resources was important. Women in

cities were especially hard-pressed, and most stood in long lines for

bread and even flour to make bread. Charlestonian Louisa McCord Smythe

reported conditions in the blockaded port in 1863: "Food was frightfully

scarce and what there was of the coarsest description. Bacon, cornbread

made with just salt and water, and biscuits made of the wheat ground up

whole, very coarse and always with only salt and water to mix them, were

the staples, in fact the only supplies of the table. Wagons were sent

from Georgia with provisions which the town distributed to those who

came for them. For hours there would be a crowd of the best sort of

people, standing in line for their chance for a little bit of

something." In Atlanta, wartime deprivation was equally dire, as a

matron described: "I knew women to walk twenty miles for a half bushel

of coarse, musty meal with which to feed their starving little ones, and

leave the impress of their feet in blood on the stones of the wayside

ere they reached home again." One woman who confronted the price of $70

a barrel for flour exclaimed: "My God! How can I pay such prices? I have

seven children; what shall I do?" This cry echoed throughout the

Confederacy.

|

BREAD LINES IN BATON ROUGE, AS SOUTHERN SHOPKEEPERS RAN OUT OF BARE

NECESSITIES FOR THE CIVILIAN POPULATION. (LC)

|

Speculators were targeted by angry mobs. In April 1863, when a

proprietor refused to lower the price of bacon, a veteran's wife drew

her pistol and allowed fellow shoppers to "liberate" food supplies.

After the fracas, witnesses—instead of calling the

police—established a fund to provide food for indigent wives of

soldiers. Donations were solicited through the local paper.

The looting of Confederate storerooms was a problem, especially in

border states, where dissent and divides were open and flagrant. Also

the Carolina and Tennessee backcountry was plagued by desertion and

Confederate disloyalty that could and did end in bitter dispute. Where

mountain folk were embittered by planter greed and disgusted by slave

owners, mutiny ruled. In Marshall, North Carolina, rebel deserters broke

into a government warehouse to obtain salt and even raided the house of

a Confederate colonel. This set in motion a series of events which led

to vicious reprisals and the Shelton Laurel Massacre when a dozen

civilians accused of guerrilla warfare were captured and executed,

including a thirteen-year-old boy and a sixty-year-old man. The Union

campaign of starving out the rebels worked most effectively in this

interior region.

While plantations were hard hit by the war in the rural South, we

know relatively less about the way the war desiccated the lives of

ordinary people. Commonly yeoman farms were stripped of sons, mules,

tools, and other means of support, especially by the war's later years.

Women took to the fields to keep their families fed because the southern

countryside was ravaged.

Louisa Henry, anchored to her Mississippi River plantation, Arcadia,

wrote to her mother in 1862: "I feel 10 years older than when the war

commenced—and look at least five years older. I can see the change

myself and my hair is turning gray rapidly." Two years later she had

been driven off her plantation and was hiding from federals in a cottage

in the woods: "Ma, sometimes I feel almost desperate, and almost

wish I could take a Rip Van Winkle sleep till all is over and

settled."

Nineteen-year-old Amanda Worthington in Mississippi stopped writing

in her diary for a year after her brother Bert died in the war but

reflected when she recommenced: "What a change has passed over my life

since last I kept a journal! Deep have I drank of the bitter waters of

sorrow and the lightness of heart that once was mine will never return

me more."

|

SOUTHERN REFUGEES FORCED TO PACK UP AND FLEE AT THE THREAT OF UNION

INVASION. (LC)

|

|

CARTOON FROM FRANK LESLIE'S ILLUSTRATED DEPICTS THE PLIGHT OF THE

CONFEDERACY HAVING TO ROB THE CRADLE AND THE GRAVE TO FILL OUT THE

RANKS. (FW)

|

Confederate losses were enormous and devastating. The Union was

winning the war through attrition—generals in gray almost always

lost a greater percentage of their fighting force. By September 1862 the

Confederate Congress was desperate enough to push through a draft law

which raised the upper limit of conscription from the age of

thirty-five to forty-five. The government compounded the problem by

instituting the infamous "twenty Negro law" in October 1862, which

exempted any white man from army service who could demonstrate a

managerial role for twenty slaves or more—both owners and overseers

qualified. (This happened shortly before the federal government

similarly antagonized its people with a clause permitting substitutions

for $300.) Poorer farm families were outraged that planters—who

could afford service by buying substitutes—were now further

legitimated if they sat out the war. These measures coincided with

failing harvests and sparked sedition and unrest.

Within the Confederacy fewer than 5,000 men were granted government

exemptions in nineteen categories ranging from occupational emergency

(apothecaries) to physical disability (blindness, for example). And of

those exempted, only 3 percent used the "twenty Negro law." On 85

percent of those plantations where white men could prove eligibility, no

exemption was taken. Nevertheless, the perception of class privilege

rankled the populace and created a public relations disaster. Even the

$500 tax levied on exemptions, instituted in May 1863, failed to mollify

critics.

|

|