|

VICTORIES AND LOSSES

Lee's surrender on April 9, 1865, ended the Confederate dream. The

preservation of the Union gave Lincoln hope, a hope cut short by his

assassination on April 14. The country, following Lincoln's wishes,

rapidly tried to reunite, to heal the bitter wounds of four years of

fratricide. Struggling back to peacetime was an enormous effort in the

North but an even more devastating prospect for white southerners.

The war not only wiped out a generation (over one-fifth of the adult

male white population in the South) but deprived descendants of

misplaced dreams of returning to prewar prosperity. Ten billion dollars

worth of property was destroyed in the region, but this "destruction"

also reflected the emancipation of millions of slaves, many by their own

liberation, and a new dawn for black hope. African Americans rejoiced in

Confederate defeat. Slavery was abolished with the passage of the

Thirteenth Amendment in December 1865, and citizenship rights were

extended to individuals of the former slave class with the Fourteenth

Amendment in July 1868. (Voting rights were reinforced by the Fifteenth

Amendment, ratified in 1870.) These legislative strides on the federal

level did little to better race relations during the social and

political ferment that followed war's end. Indeed, many southern

politicians defied the spirit of these constitutional amendments and

enacted "Black Codes," as they came to be known—laws meant to

prevent African American freedom.

The Freedmen's Bureau, established during wartime under the

leadership of General O. O. Howard (after whom Howard University is

named), and various war relief agencies tried to move into the shambles

of the postwar South to set up schools, to protect voting rights, and to

initiate economic self-sufficiency among African Americans. During the

summer of 1865 the Freedmen's Bureau distributed 150,000 daily rations

(nearly 50,000 to whites), a necessity that seemed to grow rather than

diminish as the agency passed out nearly twenty-two million rations

between 1865 and 1870.

|

CITIZENS SEARCHING THE RUINS OF A BATON ROUGE MANSION. (LSU LIBRARY)

|

|

A FREEDMAN'S SCHOOL IN THE OCCUPIED SOUTH. (LC)

|

|

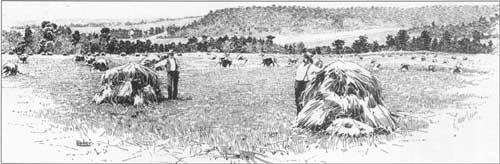

A RETURN TO FARMING NEAR "BLOODY HILL" AT THE SITE OF THE BATTLE OF

WILSON'S CREEK. (AMERICAN HERITAGE COLLECTION)

|

Defeated Confederates reeled from the consequences of their failed

rebellion. Once rich Delta lands were filled with weeds and burned out

shells of former estates.

|

Defeated Confederates reeled from the consequences of their failed

rebellion. Once rich Delta lands were filled with weeds and burned out

shells of former estates. This was in direct contrast to the stellar

record of agricultural production enjoyed in the North, where wheat

production beat prewar output, and corn, pork, and beef exports doubled,

while the Union supplied its armies and its people.

Transportation and industrialization boomed. Only the textile

industry suffered in the North (because of the shortage of raw

material). Coal production, copper processing, and other resources

accelerated from wartime demand. So much commercial growth contributed

to the Civil War being called "the Second American Revolution." Although

economic output may have slowed in some areas, the overall picture in

the 1860s is one of acute acceleration. Economists debate the question

of growth during the war years, but all agree that the sectional

redistribution of wealth was enormous. In 1860 the per capita wealth of

white southerners was 95 percent higher than that of northern whites.

That situation was reversed dramatically in 1870 when the northern per

capita wealth was 44 percent greater than that of southern whites. The

South's share of the national wealth had been 30 percent in 1860 but

shrank to 12 percent in 1870.

|

YOUNG WOMEN IN WARTIME NORTH CAROLINA. (MC)

|

The back of the plantation economy had been broken, and there seemed

no way to restore prewar patterns, despite planters' dreams. The black

work force was reluctant to return to former plantations. Although most

wanted to escape field work, without education and resources, the

majority were forced into daily wage labor. Indeed, the sharecropping

system was seen as a means to property owning by land-hungry

freedpeople. By war's end, blacks discovered that "forty acres and a

mule" was a dream rather than any federal agenda. President Andrew

Johnson's amnesty programs and congressional caution prevented the

federal government from allowing distribution of public lands, which

were plentiful. The land for black ownership need not have come from any

property held by whites. But the principle of white supremacy reigned.

Northern intervention may have allowed occasional interlopers such as

the first generation of black elected officials during Reconstruction,

including Hiram Revels and Francis L. Cardozo. The specter of black

judges, black legislators, and African Americans as local federal

officeholders alarmed former Confederates.

White men felt undermined and overwhelmed in the wake of surrender.

The 1870 census revealed 36,000 more women than men in Georgia and

25,000 more in North Carolina. In Atlanta more than 8,000 families, many

headed by women, were utterly destitute in the wake of the war. Federal

troops were a constant and visible reminder of Confederate defeat.

Georgian Fanny Andrews commented on women pulling their drapes, feigning

mourning. White women boycotted social functions where soldiers might

appear, including church, where they felt sermons were influenced by the

federal presence.

|

CONFEDERATE SPY ROSE GREENHOW AND HER DAUGHTER, UNDER HOUSE ARREST IN

WASHINGTON, BEFORE BEING CONFINED IN THE OLD CAPITOL PRISON. (LC)

|

During the summer and fall of 1865 many Confederates fled their

former homes. Brazil and Mexico hosted colonies of disenchanted former

slave owners, and Europe welcomed these aristocrats in exile as well.

Hundreds also crossed the Canadian border as refugees. But the majority

of white southerners remained in their defeated homeland.

One Georgia woman reported, "The pinch of want is making itself felt

more severely every day and we haven't the thought that we are suffering

for our country that buoyed us up during the war. Widows in the South

were deprived of the generous pensions provided families of Yankee

veterans. Despite poverty, white southerners stubbornly held on to their

pride. Many refused to take the dreaded oath (renouncing the Confederacy

and pledging loyalty to the Union) and sought federal pardons from

Lincoln's successor, Andrew Johnson, who proved an all too lenient

dispenser of mercy. Surprisingly, only Confederate president Jefferson

Davis served any time in jail and only one Confederate officer, the

infamous Commander Henry Wirz, in charge of the Andersonville Prison,

was executed for war crimes. So despite Confederate complaints to the

contrary, the federal government proved amazingly tolerant following

Union victory.

As Lincoln had predicted, once the Union was preserved, the

difficulty would be to restore the nation to order. Most ex-Confederates

wished to embalm their status by exalting the nobility of the Lost

Cause. Women were especially active in these campaigns to rewrite

history, praise southern military heroes, and paint a picture of glory

and honor in the wake of such a serious setback as presidential and

congressional Reconstruction. The United Daughters of the Confederacy

and other memorial organizations kept the Confederate cause alive well

into the next century. Indeed, it wasn't until the corrupt bargain in

the wake of the election of 1876 that the South wholly rejoined national

politics, and at the cost of black political progress, as many critics

have pointed out.

|

RUINS OF COLUMBIA, SOUTH CAROLINA. (NA)

|

But despite these setbacks, Reconstruction gave African Americans as

a group their first taste of freedom, and many seized the moment with

vigor and admirable restraint. The way southern blacks struggled for

their rights and stepped lively into political arenas is one of the

great political transformations of the millennium. Whatever happened in

the backlash that followed, former slaves shed their shackles, bidding

for their full and rightful place in the public sphere.

Following the war, many former Confederate states were forced to

contend with the discomforts of modernization. Folkways could be

supplanted by federal directives. State governments grappled with

education and reform in ways that had never been seen before south of

the Mason-Dixon line. The forced march toward fuller political

participation, literacy, and agricultural and labor reforms pulled an

unruly region more into line with its northern neighbor.

The wartime Congress could be proud of many accomplishments.

Certainly, the Homestead Act had far-reaching effects as over 500,000

settled 80 million acres by the end of the century. Additionally, the

Morrill Act paved the way for the state university system. After 1862

states were granted public lands (amounts based on a per legislator

basis) for sale, and money raised established land-grant colleges. This

was the most important and initial grant of federal aid to education.

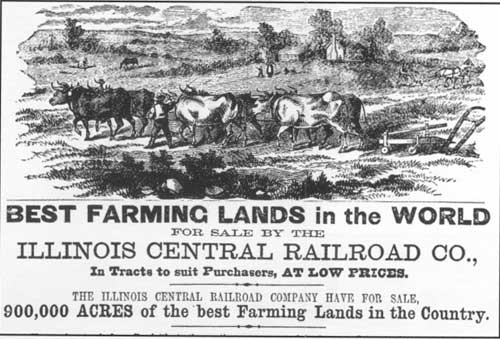

Land grants to the railroads totaled over 120 million acres. The steady

march of progress created a parade of modern legislative victories

ushering in national banking, homesteading, colleges and universities,

railroads, and, finally, the Internal Revenue Act.

|

THE EXTENSION OF THE RAILROAD CREATED A STAMPEDE WESTWARD WHERE LAND WAS

PLENTIFUL. (ADVERTISEMENT FROM HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

|

REFUGEES ON THE RICHMOND CANAL IN 1865. (LC)

|

Nevertheless, the costs of war were enormous. The Civil War resulted

in more soldiers dying than were killed in almost all subsequent wars in

American history. Almost 630,000 died, with over half a million

wounded. At Antietam on a single day nearly 4,800 were killed, whereas

less than 4,000 Americans died during the Revolutionary War. But the

impact on the national scale paled in comparison to the effect on local

communities: in Worcester, Massachusetts over 4,000 of its eligible male

population of 24,000 went to war and nearly 500 never came back. Most

homecoming reunions among Yankee soldiers were touching rather than

melodramatic affairs, as Leander Stillwell recalled. When he returned to

Otterville, Indiana, Stillwell was happily restored to his parental

home: "We all had a feeling of profound contentment and satisfaction . .

. too deep to be expressed by mere words." The next day he took off his

uniform (shedding his status as a Union lieutenant), put on his father's

old clothes, and "proceeded to wage war on the standing corn."

|

CLARA BARTON'S POSTWAR CRUSADE TRACING MISSING SOLDIERS

Once the war was over in April 1865, many families faced the harsh

reality that their husbands and brothers, fathers and sons might not be

coming home. Tens of thousands had not heard from families for months

or even years and found their inquiries to the government failed to

elicit response because the War Department was flooded with requests

following Confederate surrender. Certainly the work of identifying the

thousands buried in anonymous graves would never be completed, but

Union women dedicated themselves to trying.

Clara Barton, whose legendary war work had saved hundreds of

soldiers' lives, established a clearinghouse for the purpose of tracing

lost soldiers. This task propelled her into a controversial tangle of

issues. She began her operation even before government funds were set

aside for the task. Her search for the missing naturally led to

Andersonville, the notorious Confederate prison where so many Union

soldiers has lost their lives. She traveled to Georgia in the summer of

1865 to help identify remains and rebury the dead. But Barton found her

plans thwarted by military resistance. Caught in a bureaucratic

crossfire, she was not appointed head of a Bureau of Missing Persons but

found herself at odds with the War Department.

|

CLARA BARTON (NA)

|

Having fought military red tape throughout the war, Barton simply

sidestepped the chain of command and launched a private crusade—advertising

in newspapers, printing circulars with lists of missing men,

reaching out directly to those anxious families seeking assistance.

Barton's crusade stirred up enormous passion. She was able to locate

information on dying men soliciting soldiers who may have witnessed a

comrade's passing, so that details of death were conveyed to anxious

mothers who begged to know how their sons had died. She also was able to

sift through enemy records and discover burial information on thousands,

especially those who perished in prisons, letting wives know that their

husbands would not he coming home but also letting the government know a

veteran had died.

On occasion, Barton would track down a soldier who had disappeared

for his own reasons. In one case, a veteran raged at Barton for having

his name "Blazoned all over the Country" and said his family could just

wait until he was ready to contact them. Barton sent a stinging reply,

notifying him, "Your mother died waiting." Much more often, Barton was

an instrument of welcome reunion.

Congress finally recognized the significance of Barton's campaign and

appropriated $15,000. But by the time she closed down her operation in

1869, Barton had spent all the government money and nearly $2,000 of her

own funds. She went without salary as she and her staff processed over

63,000 letters, providing more than 22,000 families with information on

missing soldiers. Through her efforts many families were able to bury

their dead and move on with their lives.

|

But not all soldiers had a homecoming. Over twelve thousand of the

Iowa men who enlisted (half of all eligible) died: 3,500 on the

battlefield, 500 in prison, 8,500 from disease. Over 8,500 of those who

went home returned seriously disabled. In the four years of war, almost

30,000 amputations were performed. In the state of Mississippi, 20

percent of the state revenue was spent on artificial limbs in 1866.

Private Cutler Rist of the Thirty-Sixth Wisconsin had his tibia

shattered by a bullet at Cold Harbor on June 1, 1864. Two days later

surgeons removed his leg from the knee down. He was operated on again in

December 1864, when leaking fluid indicated the possibility of gangrene.

Discharged in May 1865, he hobbled home to Madison, Wisconsin. Rist,

like thousands of other soldiers, would have a permanent reminder of his

war service.

|

ONE SOLDIER WHO WOULD RETURN HOME ONLY FOR BURIAL. (LC)

|

|

THIS SHEET MUSIC ILLUSTRATION SHOWS A VACANT CHAIR, A POIGNANT SYMBOL OF

LOSS IN MANY POSTWAR HOMES. (LC)

|

Nervous diseases rapidly multiplied in the postwar years, causing

physician S. Weir Mitchell to complain about "epileptics . . . every

kind of nerve wound, palsies, horeas, stump disorders, I sometimes

wonder how we stood it." Causes and treatment of mental illnesses were

little understood during the late to mid-nineteenth century. A

surprisingly small number, a little over 800 men, were discharged from

the Union army because of mental disabilities. Despite this low number,

one medical authority at the time complained that "the number of cases

of insanity in our army is astonishing." Less than 2,500 cases of mental

illness were reported in the North during the entire war, and some

doctors suggested that they thought the war actually reduced mental

diseases. The director of a District of Columbia asylum offered

conjecture: "The mind of the country was raised by the war to a

healthier tension and more earnest devotion to healthier objects than

was largely the case amid the apathies and self-indulgences of the

long-continued peace and prosperity that preceded the great struggle."

The war, an Ohio doctor suggested, channeled energies into "new and

important spheres."

We do have evidence that opium addiction increased: not only veterans

but their wives became dependent on the drug. Horace Day argued in his

1868 medical text that opiates offered temporary relief to those "maimed

and shattered survivors from a hundred battlefields, diseased and

disabled soldiers released from hostile prisons, anguished and hopeless

wives and mothers, made so by the slaughter of those who were dearest to

them."

|

THE ERECTION OF WAR MONUMENTS AND DEDICATION CEREMONIES HELPED TO HEAL A

WOUNDED NATION. (HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

The war took an enormous emotional toll, as children lost their

childhoods, families lost loved ones, and the nation mourned the passing

of a generation of youth who could have given talents and energies and

not just their bodies to their beloved country. Like many other wars,

the scars were deep and not all visible. Burying the dead did not always

bury the memories, and the words of soldiers and loved ones continue to

haunt. The impact of this terrible contest remains very much with us

today, as statues of Civil War soldiers dot town squares from rural New

England to bustling Manhattan. As Americans moving into the twenty-first

century, our reflections on the terrible ordeal that almost tore the

country apart seem nostalgic. Yet our constant reexamination of those

issues for which so many died and so many more fought, to appreciate the

bravery of those on the home front as well as the battlefront, signals

the strengths of our American heritage, as we are condemned not to

relive our history but to fulfill the promise of our victories and

recall the memories of losses.

|

Back cover: Heart of the Southern Girl by Henry E. Kidd,

Colonial Heights, Virginia.

|

|

|