|

THE NORTHERN HOME FRONT

The northern home front rallied to the Union cause with remarkable

fervor considering that Lincoln was elected by a minority and many

blamed this first Republican president for the outbreak of war. When

South Carolina seceded, much like the fireworks over states' rights

during Andrew Jackson's presidency, when John C. Calhoun resigned as

vice-president, many Americans thought it would be another family

squabble rather than the full-scale conflict that ensued. If the battle

was a brothers' war, then Northerners cast themselves as the good and

dutiful sons loyally serving the interests of the Founding Fathers,

unlike their rebel siblings, who were willing to turn their backs on

ancestors, to grasp avariciously for themselves alone. One colonel

explicitly expressed this family metaphor to his troops: "This great

nation is your father, and has greater claim on you than anybody else in

the world . . . . This great father of yours is fighting for his life,

and the question is whether you are going to stay and help the old man

out, or whether you're going to sneak home and sit down by the chimney

corner in ease and comfort while your comrades by the thousands and

hundreds of thousands are marching, struggling, fighting and crying on

battlefields and in prison pens to put down this wicked rebellion and

save the old Union." And so paternal fealty—devotion to the

fatherland—pushed many a northern soldier onward and kept many

hitched to army life despite hardship.

|

PATRIOTIC PENNSYLVANIA LASSES POSING WHILE SEWING A FLAG AT THE

PHILADELPHIA ACADEMY OF FINE ARTS IN 1861. (LLOYD OSTENDORF COLLECTION)

|

Because so many believed in the Union cause, they met the call for

sacrifice as thousands took up arms. Panic spread fear in the streets of

Washington, D.C., during the spring of 1861. Lincoln responded with a

show of force, increasing his authority to meet the crisis. Following

Lincoln's suspension of the writ of habeus corpus, nearly 13,000 arrests

were made between 1861 and 1863 to maintain order. All individual

interests and liberties were suborned to the interests of the

state—the preservation of the Union. Women, most of all, needed to

pledge their faith to the Union—and only through such steadfast

feminine support could victory emerge.

Yankee females expressed their sentiments openly in letters to one

another. Ellen Wright of Massachusetts wrote to her friend Lucy McKim in

Pennsylvania: "Away with melancholy is the tune for us

nowadays—Chirp up . . . stir the fire—relish your lemonade and

'make believe' a little longer." Many of these girls found it harder and

harder to make believe as the death toll rose. Ellen Wright commiserated

when Dick and William (Bev) Chase, her cousins, decided to enlist in

1862. She wanted her friend Lucy to join her so they could become

nurses. When Dick died at Murfreesboro, she bitterly confessed, "There

is nothing earthly worth a life of a young man like Dick." Wright was

perhaps even more shattered when Bev, too, became a casualty of war.

Many Yankee women strongly supported the war without bloodthirsty

declarations or fiery calls for enlistment.

The patriotism of northern women was frequently contrasted to the

fierce chauvinism of female Confederates, as one Yankee primly defended:

"The feelings of Northern women are rather deep than violent; their

sense of duty is quiet and constant rather than headlong or impetuous

impulse." This notion of female devotion was integral to the Union image

of itself. Volunteerism as the secular faith swept men into the army and

women into war work, including the nursing corps.

Women as caretakers of the family well prepared them for nursing in

theory. In reality, it was considered improper for women to have such

intimate contact with strangers. Hospitals, far from the bastions of

cleanliness and order we hope they are today, had no such illusions in

the nineteenth century. These institutions were filled with filth and

carnage during the antebellum period, and wartime dramatically escalated

the degree of exposure to unpleasantries. Christian-sponsored as well as

secular efforts eased women's entrance into controversial new roles, but

it was still an uphill battle for women to contribute outside their own

homes and family.

The two largest voluntary organizations in the North during this

period were the Christian Commission and the Sanitary Commission. The

Christian Commission wanted to "promote the spiritual good of the

soldiers in the army and incidentally, their intellectual improvement

and social and physical comfort." Leaders of the Young Men's Christian

Association, temperance advocates, and members of Sunday school unions

channeled their zeal into this national organization. Spiritual welfare

was the primary focus of the group, a unified effort that crossed

sectarian lines. The board was filled with politicians and

philanthropists and held its annual meetings in the House of

Representatives, attended by important dignitaries, including, on at

least one occasion, Lincoln himself.

|

THE CONSECRATION (1861) BY GEORGE COCHRAN LAMBDIN. A SENTIMENTALIZED

RENDERING OF WOMEN'S "SACRED" ROLE IN WARTIME. (© INDIANAPOLIS

MUSEUM OF ART, JAMES S. ROBERTS FUND)

|

|

THE U.S. CHRISTIAN COMMISSION ESTABLISHED DOZENS OF BRANCHES TO

DISTRIBUTE SUPPLIES TO NEEDY SOLDIERS. (LC)

|

The Christian Commission provided a much needed coordinating system,

which funneled supplies to soldiers. By 1864 over 2,000 "delegates" were

involved in the campaign, distributing more than half a million Bibles,

half a million hymnals, and over four million "knapsack books." Funds

were solicited directly, and Yankee cities were consistently generous,

especially in the wake of a major battle. During the Wilderness

Campaign, Pittsburgh contributed $35,000, Philadelphia $50,000, and

Boston $60,000. Over the course of the war, the commission collected

nearly $6 million. Delegates were not only generous solicitors but

supportive dispensers of goods and care: handing out fresh fruits and

sweets, taking dictation from men too ill to write home, holding prayer

meetings, and passing out religious tracts. They believed in the

personal touch, a hands-on promotion of Christian values. (The social

gospel philosophy at the end of the century grew directly out of this

movement.) Their heartfelt mission was to touch the lives of Union

soldiers, to replace the families from which they had been taken. Jane

Swisshelm, who volunteered to work in Union hospitals, described an

experience:

"'What is your name?' a wounded solider at Fredericksburg asked.

'My name is mother,' she replied. 'Mother. Oh my God! I have not seen

my mother for two years. Let me feel your hand.'"

Swisshelm reported that some men feared their emotive responses might

be misconstrued as immature behavior, but she comforted most with the

thought that their soldiering was a test of their manhood, and after

being wounded, they deserved maternal care.

Scores of dedicated women workers saw their missions transformed from

genteel taskmistresses to women warriors.

|

The Sanitary Commission was a formidable institution which perhaps

drew strength from its diversity. Hundreds of ladies' aid societies

solicited and donated hospital supplies. Scores of dedicated women

workers saw their missions transformed from genteel taskmistresses to

women warriors. Many took to the podium as well, like Mary Livermore, a

teacher turned writer whose stumping on behalf of the commission reaped

tremendous rewards. Feeding the soldiers became a challenge, and a

manual on diet and cooking prepared by Annie Wittenmyer became a

standard and much appreciated contribution. Wittenmyer did on-the-job

training as superintendent of all army kitchens. Mary Shelton, Jane

Hoge, and Eliza Porter were equally significant contributors to the

commission's success.

|

CIVILIANS ENTHUSIASTICALLY SUPPORTED EFFORTS TO CHEER AND COMFORT UNION

SOLDIERS—"OUR BOYS AWAY FROM HOME"—AS SHOWN IN THIS 1861

LITHOGRAPH. (COLLECTION OF THE NEW YORK HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

The Sanitary Commission also established a transport service to

evacuate sick and wounded to hospitals. Eliza Howland and her sister

Georgeanne Woolsey contributed, along with their five other sisters and

mother, to nursing soldiers. Katherine Prescott Wormeley gave up her

role as mere philanthropist to jump into the fray of service, working in

one of the commission's "floating hospitals." Wormeley wrote of her

female comrades, "They are as efficient, wise, active as cats, merry,

light-hearted, thoroughbred and without the fearful tone of

self-devotion which sad experience makes one expect in benevolent

women." One of the most dynamic women working within and outside the

Sanitary Commission's domain, Mary Anne Bickerdyke was so beloved by

Union soldiers that they nicknamed her "mother." During her four years,

she wore a Quaker bonnet as she crisscrossed the border states, cleaning

up the messes the army left behind. Eventually, Bickerdyke became so

concerned with the fatality rate in hospitals that she set up facilities

all too near the battlefield, which made many commanders nervous.

Bickerdyke was a colorful figure and widely admired. Dorothea Dix was an

equally spirited and headstrong leader of a group of nurses, as many of

these ventures were privately funded. But estimates are as high as two

thousand women serving as nurses to the Union army. After a brief stint

of service in Washington, Louisa May Alcott returned home to

Massachusetts and penned her Hospital Sketches, followed by

Little Women and other popular titles.

|

MEMBERS OF THE SANITARY COMMISSION AT A UNION ENCAMPMENT NEAR

FREDERICKSBURG, VIRGINIA. (LC)

|

Clara Barton began her work with Massachusetts troops and soon

traveled far and wide to serve at the front. She showed up at Antietam

in an oxcart loaded down with supplies. She tried to maintain her

ladylike composure but complained that the conditions were neither fit

for men nor women on the front lines, recounting a story of a wounded

soldier shot in her arms as she gave him water. Barton suffered two

severe bouts of illness during the war, and estimates are as high as one

in ten female nurses succumbed to fatigue or disease and was forced into

bed rest. Several suffered permanent impairment, and a few died of

complications following prolonged nursing service.

|

A WARTIME ILLUSTRATION OF WOUNDED BEING TENDED TO IN A UNION HOSPITAL.

|

|

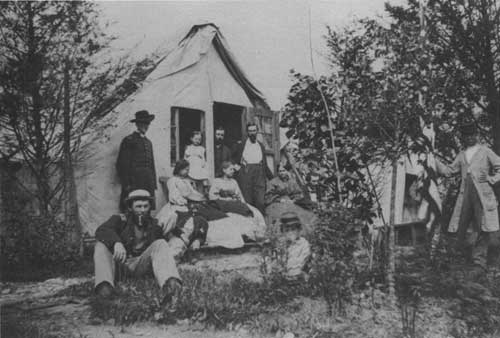

FAMILIES WERE OCCASIONALLY REUNITED IN CAMP BETWEEN BATTLES. (USAMHI)

|

Although soldiers welcomed the nurses, individual Union men raised

objections, especially about their own wives and relations endangering

themselves in army hospitals. Ulysses S. Grant said he would send his

wife home if she did not stay out of the camp hospital. Nevertheless,

tributes rather than threats were more common. Frederick Law Olmsted

praised the "glorious women" in the Sanitary Commission, commenting,

"God knows what we should have done without them, they have worked like

heroes night and day." Women worked against the prejudices of men and

earned high praise.

In 1863 Sanitary Commission worker Mary H. Thompson opened the

Chicago Hospital for Women and Children to provide an alternative for

female nurses and doctors. Later that year the New York Medical College

for Women took in its first class, and the struggle for medical

education accelerated with wartime challenges. Men's biases did not fall

by the wayside but were suspended because of wartime necessity.

Certainly the hard work women provided—to nurse and comfort, to

feed and forage, to clothe and cleanse—left men free to carry on

crushing burdens of war.

|

UNION NURSES PREVAIL CONFRONTING THE HORRORS OF WAR

Sophronia Bucklin was like many young women of her generation-bright,

committed, patriotic. When the Civil War broke out, this schoolteacher

from Auburn, New York, applied to be a nurse in the Union army. Dorothea

Dix had been appointed superintendent of women nurses in June 1861 and

exacted strict requirements from those under her supervision. Only women

over thirty and "plain in appearance" needed to apply. Despite Bucklin's

youth, she must have passed muster with Dix, as she was accepted into

the nursing corps and began her service at the Judiciary Square Hospital

in Washington.

Bucklin found her initial encounter with male medical staff

challenging. Female nurses discovered that most military officers and

surgeons were resentful of women's presence in Union hospitals. Bucklin

served the needs of her patients with a stiff upper lip but confided

that she felt the army doctors were "determined by a systematic course

of ill treatment . . . to drive women from the service."

Nevertheless, Bucklin, like thousands of women volunteers, triumphed

in the battles against the male bureaucracy and made invaluable

contributions. Her vivid memoir, In Hospital and Camp: A Woman's

Record of Thrilling Incidents Among the Wounded in the Late War

(1869), provides gripping detail. Bucklin's graphic descriptions of the

horrors of war encountered by this genteel generation of ladies are

compelling:

|

MANY PRIVATE HOMES LIKE THIS ONE NEAR WASHINGTON. D.C., WERE USED AS

INFIRMARIES DURING THE WAR. (USAMHI)

|

About the amputating tent lay large piles of human flesh—legs,

arms, feet and hands. They were strewn promiscuously about—often a

single one lying under our very feet, white and bloody—the

stiffened members seeming to be clutching offtimes at our clothing. . .

. Death met us on every hand. It was a time of intense excitement.

Scenes of fresh horror rose up before us each day. Tales of suffering

were told, which elsewhere would have well-nigh frozen the blood with

horror. We grew callous to the sight of blood. . . . A soldier came to

me one day, when I was on the field, requesting me to dress his wound,

which was in his side. He had been struck by a piece of shell, and the

cavity was deep and wide enough to insert a pint bowl. . . . Often they

[the patients] would long for a drink of clear, cold water, and lie on

the hard ground, straining the filthy river water through closely set

teeth. So tortured were we all, in fact, by this thirst, which could not

be allayed that even now, when I lift to my lips a drink of pure cold

water, I cannot swallow it without thanking God for the priceless

gift.

|

|

|