|

THE NORTHERN HOME FRONT (continued)

The northern economy, profoundly affected if not transformed by war,

thrived. The United States offered extraordinary opportunity, and the

North remained a beacon for liberty. One in five of the twenty million

northerners was foreign-born. Even more amazing, almost a quarter

million per year continued to emigrate to the United States, almost all

to the North.

Land remained the greatest lure. Over 70 percent of the northern

population resided on farms and over half of northern wage earners

worked the land. The family farm was the dream not just of immigrants,

but of a majority of Americans. Many thousands of immigrants bypassed

eastern urban centers to come to the midwestern farmlands, trying to

earn enough at day labor to buy their own land. Wartime legislators

pushed to fulfill this dream. In 1862 Congress passed the Homestead Act,

which allowed individuals to settle on 160 acres of land. After laying

claim and working their claim for five years, homesteaders obtained

deeds. In this way 2.5 million acres were distributed. Over 15,000 new

farms sprang up in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Kansas, and Nebraska

during wartime.

|

THE GOVERNMENT MADE MILLIONS OF ACRES AVAIABLE HOMESTEADING BY 1862.

KANSAS WAS A JUMPING-OFF PLACE FOR THOUSANDS SEEKING LAND IN THE WEST.

(KANSAS STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

|

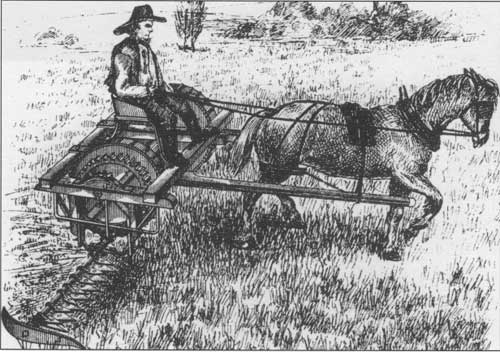

FARMERS RELIED ON MACHINES AND OTHER LABOR-SAVING DEVICES AS WORKERS

WENT OFF TO WAR. (GPO)

|

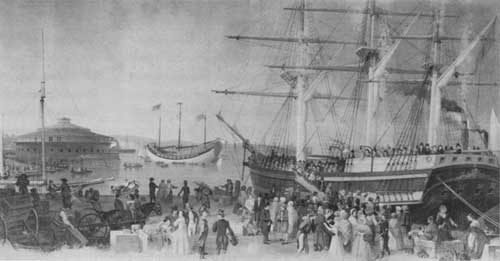

Most of the immigrants landing in America did not settle on farms,

and very few made any transition to land ownership without several

years as wage laborers. Immigrants entering the United States were

usually deposited in urban centers and ports, overcrowded and overpriced

for recently arrived greenhorns. Surprisingly, the war provided some

means of upward mobility. Immigrants could earn $13 a month by joining

the Union army. By 1862, nearly 80,000 New Yorkers out of a population

of 816,000 had joined up. Rural regions as much as urban centers

responded to the call to arms: Illinois contributed 197,000 volunteers,

Iowa 70,000, and over 75,000 enlisted from Wisconsin. Itinerant farm

workers were the first to go, as an Iowa farmer explained: "Our hired

man left to enlist just as corn planting commenced, so I shouldered my

hoe and have worked ever since. I guess my services are just as

acceptable as his."

Ironically, farm production was not hard hit but accelerated

tremendously during the war. Reaper sales grew 300 percent in response

to increased demand. Consequently, farmers increased their output and,

in addition, plentiful harvests contributed to the doubled export of

foodstuffs to Europe. The war stimulated new stock and production. With

the cotton blockade, northern farmers turned to alternatives, and the

wool trade exploded: the number of sheep in northern states grew from 15

million in 1860 to over 32 million in 1866.

Armies in the field were not just in the market for food and

clothing. Animals were a major resource for the war effort. Prices for

horses pushed slowly upward, from $100 at the outset to $185 by war's

end. The Union army used up approximately 500 horses per day by war's

end so that despite efforts to supply the insatiable demand, the horse

population in the Union dropped by nearly half a million. Mules were as

much in demand as horses. The production of cattle and hogs boomed, but

demand outstripped supply throughout the war years in the North.

Increased consumption seemed not limited just to the army; a general

upward trend in meat eating marked the war years. The hog population in

the North declined by nearly 3 million during the war years and the

production of cows slowed by nearly 800,000 in the last year of the war.

The meatpacking industry naturally boomed, and the transportation

industry exploded. Wartime witnessed the expansion of the railroad,

including successful completion of the transcontinental railroad in

1864.

Businessmen and entrepreneurs, thrown into confusion by the outbreak

of war, finally hit their stride by 1862. Although over 3,000 companies

failed in the first twelve months of the war and an income tax was

introduced in 1861, the economy began to bounce back as manufacturing

thrived. For example, in Philadelphia, the growth of factories marked

rapid expansion: fifty-eight new factories in 1862, fifty-seven in 1863,

and sixty-three in 1864. The shoe and textile industry grew, and the war

ushered in standardized sizes for clothing. The number of sewing

machines in use doubled between 1861 and 1865.

The same year that the war erupted a successful young Scot named

Andrew Carnegie formed the Columbia Oil Company. After drilling on the

Allegheny yielded 20 barrels a day in 1857, the petroleum industry was

poised to launch itself. The young John D. Rockefeller had built himself

an oil refinery on the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, Ohio. (Both Carnegie

and Rockefeller bought themselves substitutes rather than get drafted.)

The Comstock Lode near Virginia City, Nevada, provided its owners with

$15 million worth of ore annually.

|

EUROPEANS POURED INTO AMERICA THROUGH NEW YORK'S CASTLE CLINTON ON

MANHATTAN'S SOUTHERN TIP AS DEPICTED IN SAMUEL WAUGH'S PAINTING THE

BAY AND HARBOR OF NEW YORK. (MUSEUM OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK)

|

|

THE GENERAL STORE BECAME A CENTER FOR WAR NEWS AS WELL AS A PLACE TO

BARTER AND BUY SUPPLIES. (USAMHI)

|

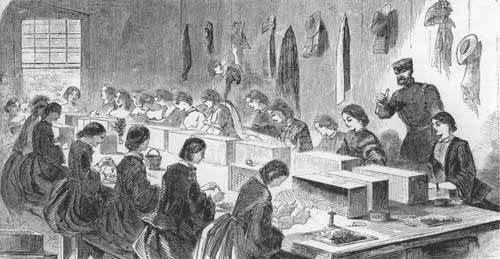

|

MACHINERY AND PATRIOTISM FUELED THE BOOM IN CLOTHING MANUFACTURE.

(HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

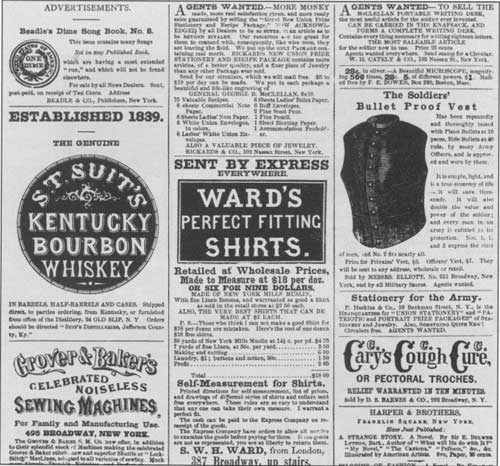

But as business grew, so did speculation and graft. Smuggling became

a particularly lucrative part of the northern economy as colonels and

quartermasters engineered illicit deals with planters in the southern

states. When cotton was ten to twenty cents a pound in Memphis in 1864,

it sold for over $1 a pound in Boston. Conversely, while salt sold for

$1.25 in the North, an identical amount cost $60 in the southern

states.

Certainly inflation hit in the North, and wages were unable to keep

pace. While a dozen eggs cost fifteen cents in 1861, by 1864 the price

had risen to twenty-five cents. The average daily wage (pegged to a male

worker) rose from $1 to only $1.25. While business boomed, labor did not

fare so well. Clothing manufacturing thrived, but seamstresses certainly

did not. The six-day-a-week, fourteen-hour day netted a seamstress a

week's wages of under $2. Northern workers found a 20 percent decline in

real earnings as a result of wartime inflation. The wartime labor

surplus did not shift into labor shortage until 1862. By the later years

of the war, many women replaced men in the fields throughout the North.

One observer watched "a stout matron whose sons are in the army with her

team cutting hay. . She cut seven acres with ease in a day, riding

leisurely on her cutter." This ease and leisure was not typical. The

majority of Yankee women, like poor seamstresses, struggled for economic

survival during hard times. Females increased their proportion of the

manufacturing work force (from one-fourth to one-third) but were

confined to low-paying sectors, and because of inequities in pay, their

increase depressed manufacturing wages. During the last year of the war,

real wages in many trades returned to prewar levels and the North was

plagued with the problem of worker unrest resulting in violence,

strikes, and other labor disputes. Most of these slowdowns and strikes

were met with armed resistance and government intervention.

When workers at a munitions factory in Cold Spring, New York, went on

strike, the factory owner was able to call in the army to throw strike

leaders into jail and restore order. Dock workers in New York were

stripped of their pay and locked in the yards when they tried to use

organizing tactics. Army troops were brought in and arsenal workers

labored at bayonet point in Nashville, Tennessee, after threatening a

walkout. "Free labor" had been a battle cry of the Republican party, but

once the war was under way labor found itself in the government's thrall

and less free than at any other time in the history of labor

organization. Railroad engineers, munitions workers, and stevedores were

especially vulnerable, as the Union government tolerated no dissent in

these war-related industries.

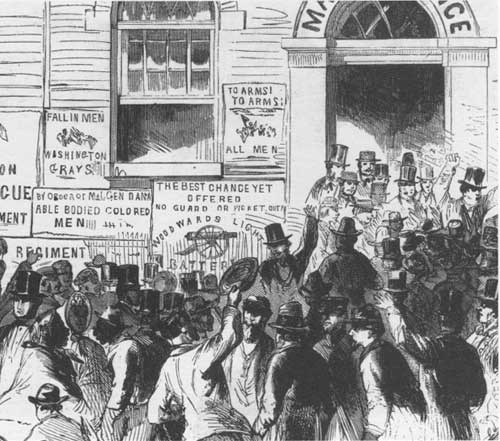

Unrest on the civilian front became an increasing problem as the war

wore on. In the wake of northern defeat at Bull Run, over 90,000 men

enlisted in less than a month, and over half a million volunteered by

November. But when calls for troops were renewed in the summer of 1862,

300,000 recruits were desperately needed. Each recruit received a $100

bounty from the federal government. As each community and state set its

own quotas and paid its own bounties, recruits might be paid as much as

$500 to enlist. But even these financial incentives were increasingly

unsuccessful.

Bounty jumping and hiring substitutes increased with the publication

of the death lists. More and more men sought alternatives to joining up.

Draft resistance became widespread, and Canada welcomed almost 100,000

men during wartime; almost a third were deserters. Draft dodgers who

escaped used the "skedaddle quickstep" as it was called, which reached

such epidemic proportions that states such as Iowa passed laws against

young men emigrating without passes and the federal government forced

Canada to restrict immigration. Nearly 800,000 were called in four

drafts between the summer of 1863 and spring of 1865. During this same

period 200,000 failed to report and an equal number of deserters left

the ranks.

|

NOTICES FOR BULLETPROOF VESTS JOINED STANDARD ADVERTISEMENTS FOR

CLOTHING AND MEDICINES AND OTHER GOODS DURING WARTIME IN THIS

HARPER'S WEEKLY ADVERTISEMENT.

|

|

WOMEN WORKED IN A WATERTOWN, MASSACHUSETTS, ARSENAL ASSEMBLING

CARTIDGES. THE MUNITIONS INDUSTRY COULD AND DID PROVE DANGEROUS TO THOSE

WORKERS CAUGHT IN INFREQUENT BUT DEADLY FACTORY EXPLOSIONS. (HARPER'S

WEEKLY)

|

|

RECRUITMENT WAS ESSENTIAL TO THE UNION EFFORT. RALLIES SUCH AS THIS ONE

IN PHILADELPHIA WERE IMPORTANT TO BOOSTING SAGGING NORTHERN MORALE. (LC)

|

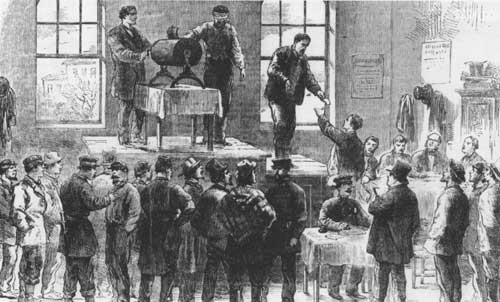

By as early as August 1862 it was impossible to fulfill state quotas.

Accommodating doctors were willing to sell certificates of unfitness. In

response, the press aggressively published "cowards lists" to shame men

into uniform. At the same time civilian agitation was a dangerous

proposition for recruiters. When Congress passed the Conscription Act in

March 1863, all men between twenty and forty-five were required to

register. Feelings against the draft were exacerbated by the provision

that allowed men who could afford it to pay $300 and buy their way out

of army service. By the summer of 1863, over 26,000 substitutions had

been purchased. Widespread dissent festered, erupting into violence in

New York City in July 1863.

When names of draftees were drawn on July 11, on the heels of

victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, where the Union had sustained

devastating losses, protesters were unwilling to make further

sacrifices. Democratic agitators stirred protesters into a frenzy with

radical rhetoric. New York governor Horatio Seymour proclaimed "that the

bloody and treasonable and revolutionary doctrine of public necessity

can be proclaimed by a mob as well as by a government." Mobs of

unskilled workers, many Irish laborers and their families, roamed the

city to exact a toll beginning July 12, and vigilantism and violence

followed in their wake.

The violence was extreme and politically motivated—draft offices

and merchants were favorite targets. Vandals broke into Brooks Brothers

and helped themselves to expensive clothing, contemptuous of the moneyed

classes. Draft offices were burned, recruiters were targeted, and any

well-dressed bystander might be seized and attacked as a "$300 man."

Store windows were smashed and looted and recruiters' homes were burned.

For three days the rampage continued, nearly unabated.

|

CONSCRIPTION AT A NEW YORK CITY DRAFT OFFICE. (LC)

|

|

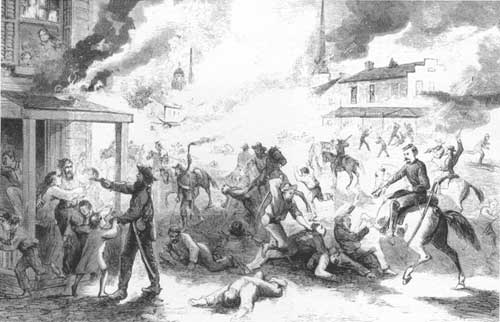

SCENES OF VIOLENCE DURING DRAFT RIOTS IN MANHATTAN IN JULY 1863.

(HARPER'S WEEKLY)

|

A special brutality and vengeance was reserved for blacks during this

violent spree. Racism reared its ugly head and devoured all sense and

reason during these riots. Black homes, boardinghouses, churches, and

even a black orphanage were burned to the ground. Lynchings were

perpetrated while the police remained helpless. The chief of police was

beaten unconscious as his men and federal soldiers attempted to restore

order. Diarist George Templeton Strong described the mayhem on July 14:

"Fire bells clanking as they have at intervals through the evening . . .

Shops were cleaned out and a black man hanged in Carmine Street for no

offense but that of negritude." On the fourth day of the riot,

troops marched in from Gettysburg to help put down the violence. Over

100 people were killed, hundreds more injured, and it took over forty

regiments ringing the city to restore order.

Following the draft riots, African Americans fled New York City in

large numbers, which reduced the labor pool and improved white wages.

The city council voted $2 million to buy substitutes for any policeman,

fireman, or member of the militia who was drafted and couldn't afford to

pay. Additionally, any New Yorker who could prove that enlistment would

impoverish his family was granted a substitute stipend to fight off the

draft. Records indicate that few of those caught committing crimes and

mayhem during the riot had criminal records and nearly a third of the

male participants were not themselves threatened by the draft but merely

sympathetic to the protest. Women and children, and especially

immigrants, played a disproportionate role in the violent uprising. Most

grand juries refused to indict those arrested, and few received any

punishment for their violent acts and even the murders that

resulted.

New York City was not alone in its violent uprising. Disturbances

broke out in Boston and Troy of a similar character, but none were as

bloody and destructive as this draft riot for three long days in July.

Massive protests in Chicago's roughest ward, "The Patch" turned out

nearly three thousand to protest the draft. When arrests were made,

bricks and bottles rained down on the police, who released their

captives. When a provost marshal decided to bring in soldiers to quell

the riots, workers from a local quarry met the men with clubs and

stones. Throughout the North local politicians faced increasingly

impossible dilemmas—to keep their constituents happy while meeting

war demands from the federal government. Union troops were called into

the mining districts of Pennsylvania because Irish miners felt as abused

by the draft recruiters as they had by English landlords. When quotas

weren't met and disorder threatened, Lincoln cautioned the Pennsylvania

governor that saving face was important but not at further political

costs—and the unfilled slots were stuffed with men who had once

lived or even been born in those mining counties where eligible

immigrants resisted recruiters.

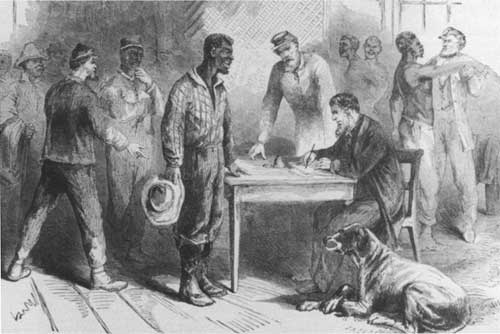

|

AFRICAN AMERICANS WERE KEY TO FILLING NORTHERN DRAFT QUOTAS, AS FORMER

SLAVES COLLECTED BOUNTIES AS SUBSTITUTES. (FW)

|

Disorder and unrest plagued the Union in a variety of spheres

during wartime. Most vexing were the border states, which fostered

guerrilla warfare at its most vicious.

|

Disorder and unrest plagued the Union in a variety of spheres during

wartime. Most vexing were the border states, which fostered guerrilla

warfare at its most vicious. Missouri was contested terrain throughout

the war, with two governments—Confederate and federal—wrestling

for control of the population. This state suffered the second

largest number of armed encounters (after Virginia) and was a land awash

with blood from decades of violence. Union guerrilla leader James H.

Lane began by targeting homes that hosted rebel forces but ended with

the wholesale plunder of towns and counties. His even more bloody

opponent, Confederate Captain William C. Quantrill, began his career

opposing slavery but ended as a leader of the Bushwhackers, Confederate

guerrillas. He launched a raid on Lawrence, Kansas, an antislavery

stronghold, on August 21, 1863, marching nearly five hundred of his men

into the town in the early morning hours. Reputedly, while Quantrill

breakfasted, his men butchered nearly 150 men and boys, most unarmed,

while women and children were forced to witness the barbaric executions.

The town was burned to the ground except the saloon, which they looted

and left standing.

|

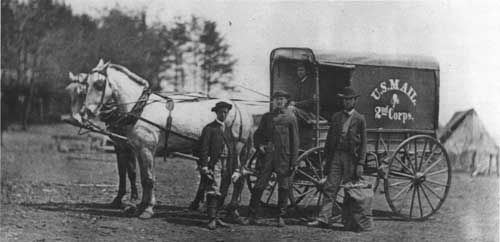

MAIL DELIVERY BECAME EVEN MORE IMPORTANT DURING WARTIME FOR FAMILIES OF

SOLDIERS, AS WELL AS THE MEN IN CAMPS FAR FROM HOME. (USAMHI)

|

|

CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTORS AND THE UNION

Many groups that had fought long and hard to defeat slavery, most

notably the Society of Friends (known as Quakers), were thrown into a

crisis with the outbreak of war. Although most wanted the slave power

defeated and the Confederacy restored to the Union, many Quakers were

devout pacifists. Quaker abolitionists had spearheaded campaigns

protesting the Mexican War in 1848. Lincoln's call to arms in 1861, even

for a good cause, created a dilemma for devout Quakers.

The Union created many loopholes for those drafted. The payment of

$300 could delay conscription—but only by securing a substitute, a

practice frowned upon by members of the Society of Friends, could

military service be permanently avoided.

|

ELDER FREDERICK W. EVANS (COURTESY OF HANCOCK SHAKER VILLAGE,

PITTSFIELD, MA)

|

Moral objections were dismissed by recruiters, as men were forced

into the army despite religious convictions. Cyrus Pringle, a Quaker

from Burlington, Vermont, described his experience in July 1863,

compelled to enlist against his will. The Union army was desperate for

able-bodied men and wouldn't allow Quaker draftees the luxury of a

conscience, as Pringle complained in his diary about debates with

officers: "They are utterly unable to comprehend the pure Christianity

and spirituality of our principles. They have long stiffened their necks

in their own strength. They have stopped their ears to the voice of the

Spirit, and hardened their hearts to his influences. They see no duty

higher than that to country. What shall we receive at their hands?"

Pringle and his fellow Quakers were held in the guardhouse, pending an

appeal to Washington. The response from headquarters was disappointing

to the pacifists: "The President, though sympathizing with those in our

situation, felt bound by the Conscription Act, and felt liberty, in view

of his oath to execute laws, to do no more than detail us from active

service to hospital duty, or to the charge of the colored refugees."

An even better organized and adamant opposition to war service was

begun by the Shakers, followers of Mother Ann Lee. Nearly 6,000 Shakers

lived in twenty settlements scattered throughout the North. Church

elders sent their representatives directly to Washington to plead their

cause: "As we have received the grace of God in Christ, by the gospel,

and are called to follow peace with all men, we cannot, consistent with

our faith and conscience, bear the arms of war for the purposes of

shedding the blood of any, or do anything to justify or encourage it in

others." They demanded total financial exemption, which Secretary of War

Edwin M. Stanton refused. But when Shaker elder Frederick Evans pointed

out that pension payments to veterans of the War of 1812 were owed to

scores of men within his community who had become Shakers following

military service and that these payments would create an enormous

financial penalty, Stanton relented. If the Shakers were granted total

immunity, the sum would be forgiven, a bargain federal authorities

happily approved. Shakers were the only group granted such a sweeping

exemption.

|

This senseless slaughter of civilians led Union General Thomas Ewing

to issue Order No. 11, which required the evacuation of four Missouri

counties while Union guerrillas, known as Jayhawkers, had their revenge.

A sympathetic federal officer condemned the exodus: "It is heart sickening

to see what I have seen here." He went on to decry the looting

and pillaging, while near naked families stumbled onto the barren

prairie. Confederates retaliated with renewed efforts to stage a coup

against Union authorities, and Confederate General Sterling Price

invaded with 12,000 troops. Rebel forces were turned back at the Battle

of Pilot's Knob before being chased all the way from northeastern

Missouri back into Arkansas. Many stragglers followed Quantrill to

Texas, but the spirit of counterrebellion had been broken. Missouri

guerrillas splintered into bands, none more infamous than "Bloody Bill"

Anderson, who was said to ride into battle with a necklace of Union

scalps round his neck, encouraging his men to mutilate the bodies of

victims. Although a populist uprising against the Union never

materialized in Missouri, guerrilla fighters, such as Frank and Jesse

James, fought on for the Confederate cause, fomenting rebellion in the

interior, creating panic among civilians caught in the crossfire of war

on the northern frontier.

|

MURDER AND MAYHEM ERUPTED DURING QUANTRILL'S INFAMOUS RAID OF LAWRENCE,

KANAS, IN AUGUST 1863, WHEN DOZENS OF UNION SUPPORTERS DIED AND THE TOWN

WAS DESTROYED. (FW)

|

|

AN 1864 ANTI-LINCOLN POSTER F0R THE PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN. (THE LINCOLN

MUSEUM, FT. WAYNE, INDIANA)

|

By 1864, the North grimly faced another year of battle, and Lincoln's

chances looked slim. Confederates took advantage of the Union's

inability to capitalize on its victories and press for peace.

Confederate raider Jubal Early roamed the northern countryside and on

July 30 demanded a ransom of half a million dollars to spare the town of

Chambershurg, Pennsylvania. When the townspeople failed to pay, Early

torched the business district and destroyed the heart of the city. That

very same day, Union General Ambrose E. Burnside's scheme to tunnel

under Confederate lines and blow his enemies up with gunpowder

backfired. The tunnel exploded and over a thousand troops surrendered

after being caught in a terrible "crater." The federals lost nearly

5,000 troops in the fiasco. Horace Greeley complained, "Our bleeding,

bankrupt and almost dying country longs for peace, shudders at the

prospect of further wholesale devastation, of new rivers of human

blood." Indeed, as the war dragged into its fourth year, Lincoln looked

to the South, to General William T. Sherman to crush the southern

spirit, which was bending but refused to break. The surprise of

Lincoln's reelection in November 1864 invigorated Union efforts to

defeat the Confederate bid for independence once and for all.

|

|