|

THE BATTLES FOR CHATTANOOGA

The autumn of 1863 was a season of shattered hopes. In the North, the

fall of Vicksburg and the turning back of Lee's invasion of

Pennsylvania in July had raised expectations of an end to hostilities

before Christmas. When Major General William Starke Rosecrans maneuvered

General Braxton Bragg out of Tennessee that same month, victory seemed

near on all fronts. But the Army of the Potomac failed to follow up its

triumph at Gettysburg and Ulysses S. Grant saw his army at Vicksburg

carved up to support peripheral operations. Then in September,

Rosecrans's Army of the Cumberland came to grief along the banks of

Chickamauga Creek, twelve miles southeast of Chattanooga, Tennessee. In

some of the bitterest fighting of the war, Bragg shattered the Union

center and sent half the Federal army reeling toward Chattanooga in

chaos. Only a stubborn stand by Major General George Thomas with the

remainder of the army averted catastrophe. As it was, Rosecrans retired

into the inner defenses of Chattanooga, too dazed to do more than await

the inevitable Confederate attack.

But it never came. As Chickamauga brought a halt to the grand Federal

offensives of 1863, so too did it represent a squandering of the South's

last chance to turn the tide of the war in the West. Bragg had no

inclination to storm Chattanooga, and the first Confederate troops did

not appear on the outskirts of the city until two days after

Chickamauga. Bragg was on the attack, but the object of his offensive

was his own generals. At the very time his attention should have been

given over to preventing the demoralized Federal army from consolidating

its defenses around Chattanooga, Bragg expended his energy rousting out

his detractors within the Army of Tennessee. Disgusted with Bragg's

repeated failings in battle and repelled by his acerbic temperament, on

October 4 twelve of his most senior generals submitted a petition to

President Jefferson Davis, calling for Bragg's removal from command.

Among the signatories were Lieutenant Generals James Longstreet, who had

come from Virginia with his corps to take part in the Battle of

Chickamauga, Daniel Harvey Hill, and Simon B. Buckner.

|

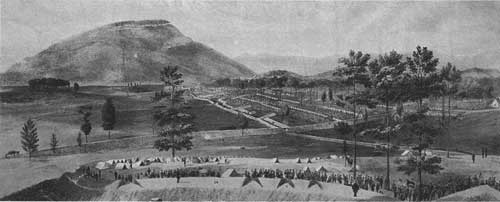

A PANORAMIC VIEW OF CHATTANOOGA, TENNESSEE, TAKEN IN JULY 1864.

(CHATTANOOGA REGIONAL HISTORY MUSEUM)

(click on image for a PDF version)

|

Davis traveled at once to the army. He listened to the complaints of

Bragg's factious subordinates and to the commanding general's

rebuttals. In the end, Davis sustained Bragg, who turned the tables on

the conspirators. He relieved Hill and Buckner, then reshuffled the

units of their corps and that of Leonidas Polk, who had been suspended

from command immediately after Chickamauga, so as to dig out the roots

of the opposition.

The reconfigured army consisted of three corps. Kentuckian John C.

Breckinridge commanded a corps consisting of three divisions, led by

Alexander P. Stewart, William Bate, and J. Patton Anderson.

Longstreet kept his corps, less one division on loan from the Army of

Tennessee that Bragg broke up, and a second that he transferred to

Polk's old corps. The two remaining divisions, which Longstreet had

brought with him from Virginia, were led by Brigadier General Micah

Jenkins and Major General Lafayette McLaws. Between Bragg and Longstreet

there could be no reconciliation. When his effort to unseat Bragg

failed, Longstreet sulked. Bragg continued to hold him in high regard as

a commander and entrusted him with key assignments early in the

campaign, unaware that Longstreet had no inclination to obey orders.

Polk's former corps went to Lieutenant General William J. Hardee,

then in Mississippi. Hardee had little to do after the fall of Vicksburg

and, despite his distaste for Bragg, he was glad to return to the

army.

The men in ranks shared their generals' low opinion of Bragg.

"Everyone here curses Bragg," a young Tennessee lieutenant wrote home.

Only Bragg's removal, he went on, would put the troops in good spirits.

The dismembering of divisions and brigades eroded morale further.

Desertions climbed at an alarming rate: 2,149 for the months of

September and October alone.

. . .there was little chance of Rosecrans recovering his strength.

Chickamauga had wrecked him. His strategic thinking was fuzzy, and he

lacked the strength to sustain a coherent effort to relieve his

beleaguered army.

|

More than just bad generalship drove the Rebels to desert. Rations

were short and shelter scarce, hardships the men could more readily have

endured had they felt Bragg had some strategy in mind beyond waiting for

the Federals to starve first. But, a Virginian bemoaned in early

October, "Bragg is so much afraid of doing something which would look

like taking advantage of an enemy that he does nothing. He would not

strike Rosecrans another blow until he has recovered his strength and

announces himself ready. Our great victory of [Chickamauga] has been

turned to ashes."

But there was little chance of Rosecrans recovering his strength.

Chickamauga had wrecked him. His strategic thinking was fuzzy, and he

lacked the strength to sustain a coherent effort to relieve his

beleaguered army.

Certainly the task before Rosecrans was daunting enough to give any

commander pause. Few cities were both so vulnerable to siege or offered

topographical features so favorable to the defense as Chattanooga.

Natural obstacles of imposing grandeur encircled it. If protected, they

might keep a besieging army at bay indefinitely, but Rosecrans had lost

them to Bragg without firing a shot in their defense, so the Federals

found themselves ensnared between a wide river and a series of long

ridges and craggy bluffs.

|

CHATTANOOGA AND THE TENNESSEE RIVER AS SEEN FROM THE TOP OF LOOKOUT

MOUNTAIN A YEAR AFTER THE BATTLE. (USAMHI)

|

Chattanooga lay in a bend of the Tennessee River, which turned

abruptly to the south just beyond the city, continuing in that direction

for two miles before butting up against Lookout Mountain. A half-mile

beyond the base of Lookout Mountain, the river veered nearly due north.

It flowed north for two miles before forking at Williams Island. These

two major changes of the river's course after Chattanooga—first to

the south, then back to the north—created a long, narrow peninsula

opposite Lookout Mountain that was called Moccasin Point.

From many miles northeast of Chattanooga to the southern tip of

Williams Island, the Tennessee River held steady at a width of three to

five hundred yards, its current gentle and waters placid. Where the two

branches reunited north of the island, the river turned narrow and

rapid. After thirteen miles of dizzying twists and foaming water, the

river calmed and widened near Kelley's Ferry, which lay six miles west

of the northern tip of Lookout Mountain. From Kelley's Ferry, the

Tennessee was easily navigable all the way to the Federal supply depot

at Bridgeport, Alabama, twenty-two miles away.

The ground east of Chattanooga was nearly as formidable a barrier as

the river. Two miles beyond the town, rising from a broad and partly

cleared valley to a height of nearly five hundred feet, loomed

Missionary Ridge.

|

A PERIOD MAP SHOWING THE CHATTANOOGA AREA DURING THE CAMPAIGN.

(BL)

|

Missionary Ridge grew out of the southern bank of South Chickamauga

Creek, which emptied into the Tennessee River two and a half miles northeast

of the city. Bisected by wagon roads, broken by ravines, dotted

with huge outcroppings, and tangled with fallen timber, Missionary Ridge

ran south by slightly southeast for nearly fifteen miles. Hard to

ascend along its entire length, its slopes were particularly precipitous

along the eight-mile stretch from South Chickamauga Creek to Rossville,

Georgia, where a narrow gap sliced through the ridge.

Missionary Ridge was separated from its more spectacular sister

elevation to the west, Lookout Mountain, by the four-mile-wide

Chattanooga Creek, which flowed north, then curved west to empty into

the Tennessee River at the base of Lookout.

Lookout Mountain was not a single mountain in the commonly understood

sense but a long, towering ridge that extended southward from the

Tennessee river eighty-five miles. Lookout Mountain narrowed as it

neared the river, coming to a point two hundred yards wide and eighteen

hundred feet above the Tennessee.

From the riverbank, the mountain first rose at a forty-five-degree

angle. About two-thirds of the way between the river and the summit, the

slope rose sharply, then changed grade and became relatively level

before terminating in a ledge, or "bench," between 150 and 300 feet

wide, which extended for several miles around both sides of the

mountain.

From the bench, the grade again became steep. Five hundred feet of

timber and outcrops brought one to the "palisades," which a war

correspondent described as "a ridge of dark, cold, gray rocks, bare even

of moss, which rise to the height of fifty or sixty feet."

West of Lookout Mountain loomed Sand Mountain. A long valley of

varying width and names divided Sand from Lookout Mountain. Of similar

length, Sand Mountain was cut by the mile-wide Running Water Creek

Valley five miles south of the Tennessee River. The mountain resumed

north of the valley, and this final stretch was called Raccoon Mountain.

It lay two miles west of Lookout Mountain. Near the river, the plain

separating the two ranges was known as Lookout Valley. A narrow stream

called Lookout Creek ran along the western side of Lookout Mountain and

emptied into the Tennessee north of the point of the mountain. On either

side of the valley, a chain of foothills rubbed against the two

mountains.

Of course, this mosaic of natural obstacles rendered lines of supply

and communications into Chattanooga from the north and west extremely

vulnerable. Confederate depredations and Bragg's tightening noose around

Chattanooga forced Rosecrans to use the longest and most indirect route,

an excruciating course through the mountains nearly sixty miles in

length, to bring supplies from Bridgeport, Alabama, into the city.

|

WHEELER'S CONFEDERATE CAVALRY CAPTURE A SUPPLY TRAIN. ILLUSTRATION BY J.

T. E. HILLEN. (NY PUBLIC LIBRARY PRINT COLLECTION)

|

As September drew to a close, heavy rains began to fall. Roads were

beaten to paste, and in the mountains, long stretches were washed away.

The Confederates made common cause with nature. On October 1, Major

General Joseph Wheeler's cavalry descended on an eight-hundred-wagon

train rumbling over Walden's Ridge, burning the wagons and shooting the

mules.

Wheeler's raid was "the funeral pyre of Rosecrans in top command."

Three Federal divisions were left without supplies, and the ammunition

reserves of the entire army were rendered dangerously low. By

mid-October, the Army of the Cumberland was on the brink of

starvation.

An unparalleled opportunity had been presented to Bragg, but he was

too absorbed in his internecine struggles to fashion a coherent plan for

compelling the Federals to abandon Chattanooga. Bragg's actions against

the Federal army at Chattanooga during October were little better than a

series of poorly thought out, makeshift measures conceived during the

odd moments between battles with his generals.

|

THE ARMY OF THE CUMBERLAND IS SHOWN

CAMPED IN FRONT OF CHATTANOOGA WITH LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN IN THE BACKGROUND

IN THIS NINETEENTH CENTURY LITHOGRAPH. (ANNE E. K. BROWN MILITARY

COLLECTION, BROWN UNIV. LIBRARY)

|

His troop dispositions offered little possibility of anything more. A

direct assault was out of the question. Bragg had a mere forty-six

thousand infantrymen stretched out along a seven-mile front that ran

from the foot of Lookout Mountain to Missionary Ridge and then northward

along the base of the ridge to a point a half-mile south of the

Chattanooga and Cleveland Railroad. Bragg lacked even the troops needed

to extend the line to the Tennessee River, which was the only way truly

to hem in the Federals. Instead, Bragg shook out a thin picket line up

the riverbank as far as the mouth of South Chickamauga Creek to guard

against crossings beyond his right flank. Longstreet's corps held the

line from the base of Lookout Mountain to the west bank of Chattanooga

Creek; Breckinridge occupied the center from the east bank to the Bird's

Mill road across Missionary Ridge, and Polk's old corps—temporarily

commanded by Benjamin Franklin Cheatham—completed the line along

the foot of the ridge. Tucked behind a chain of earthen redoubts and

rifle pits, the Federals were a mile or more beyond the attenuated Rebel

main line in most places. Their lines, by contrast, were neatly

compact. Extending from bank to bank of the Tennessee, they formed a

half-circle around Chattanooga three miles long. Opposing pickets were

often less than two hundred yards apart, placed so as to give ample

warning of an advance by either side.

Not that anyone was about to move. Rosecrans had neither the will nor

the horses needed to move his army. And Bragg spent his time sulking

about headquarters reading, with little interest, ciphered messages

warning of the approach of five Yankee divisions under Major General

William T. Sherman from Mississippi.

Victory at Vicksburg had been barren for Major General Ulysses S.

Grant. After the city's fall in July 1862, General in Chief Henry

Halleck began carving up Grant's army to enable Union forces west of the

Mississippi to "clean up a little in the weaker Trans-Mississippi

Department before undertaking anything ambitious against the stronger

half of the Confederacy." Only the defeat of the Army of the Cumberland

at Chickamauga and its retreat to Chattanooga saved Grant from being

shunted aside by Halleck, who was always jealous of Grant's successes.

On September 29, six days after Halleck ordered Grant to send William T.

Sherman to Chattanooga, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton directed Grant to

go to Chattanooga himself as commander of the newly created Military

Division of the Mississippi, an enormous field command that was to be

composed of three departments: the Department of the Ohio, then under

Major General Ambrose Burnside; the Department of the Cumberland, under

Rosecrans; and Grant's own Department of the Tennessee. In effect, all

the territory from the Appalachians to the Mississippi River and

including much of the state of Arkansas was to be unified under one

commander. Grant was given the option of retaining or dismissing

Rosecrans; he chose to replace Rosecrans with his senior corps

commander, Major General George H. Thomas.

|

|