(click on image for a PDF version)

|

ORCHARD KNOB IN FEDERAL POSSESSION, NOVEMBER 23

On November 23, Grant ordered Thomas to conduct a demonstration against

the Confederate picket line. The point selected was Orchard Knob. At

1:30 P.M., Wood's and Sheridan's divisions of Granger's 4th Corps

advanced from the Federal lines around Chattanooga and took Orchard Knob

from the surprised Confederates.

The Federal attack caused Bragg to recall Cleburne's Division. Cleburne

bivouacked for the night north of Bragg's headquarters. The Confederates

also began to construct fortifications on the crest of Missionary

Ridge.

Sherman's troops, encamped out of sight behind hills north of

Chattanooga, prepared to move to the point selected for their crossing

of the Tennessee River just downstream from the mouth of South

Chickamauga Creek.

|

Daylight on November 23 revealed the immediate objective of Wood's

foray: a craggy knoll, two thousand yards east of Fort Wood, known as

Orchard Knob. Rising sharply one hundred feet above the Chattanooga

Valley, the knob was covered with small trees and a line of rifle

pickets occupied by Rebel picket reserves.

Under chilly but crystal blue autumn skies, Wood's 8,000 infantrymen

marched out of their entrenchments and formed ranks with parade ground

precision. Phil Sheridan's division, under orders to protect Wood's

right flank, lined up with equal exactitude. On Wood's left, Howard's

Eleventh Corps extended the Federal line to Citico Creek.

By 1:15 P.M., nearly 20,000 bluecoats stood at attention in the broad

valley between the opposing picket lines. Grant, Thomas, Hooker, Howard,

and Assistant Secretary of War Charles Dana all came out to watch the

performance.

At 1:30 P.M., buglers blew the command "Forward," and Wood's and

Sheridan's long lines sprang forward at the double-quick time. The

Federal infantry swept across the plain, covering 800 yards before the

stunned Rebels opened fire. Before they could reload, Yankee skirmishers

were upon them, rounding up prisoners and pursuing the rest toward the

knob.

|

A VIEW OF MISSIONARY RIDGE FROM ORCHARD KNOB SHORTLY AFTER THE BATTLE.

(LC)

|

Six hundred bewildered Rebels confronted the advance of nearly

14,000 Federals. They exacted a heavy toll on the attackers, but the

issue was never in doubt. Those Southerners not shot or captured

retreated to the base of Missionary Ridge.

A few minutes before 3:00 P.M., Wood signaled General Thomas: "I have

carried the first line of the enemy's entrenchments." What were Thomas's

instructions?

Grant and Thomas consulted briefly. Both hesitated: Wood had done far

more than conduct a mere reconnaissance; should he be recalled as

planned? Rawlins broke the impasse: "It will have a bad effect to let

them come back and try it over again." Grant took the advice: "Intrench

them and send up support," he told Thomas.

As the sun set and a deep chill fell over the valley, Bragg

emerged from his daze. He readjusted his lines and recalled every

unit within a day's march to meet what he now realized was a serious

threat against his unprotected right.

|

As the sun set and a deep chill fell over the valley, Bragg emerged

from his daze. He readjusted his lines and recalled every unit within a

day's march to meet what he now realized was a serious threat against

his unprotected right. Cleburne's division, which had not yet boarded

the cars at Chickamauga Station, returned after dark. General Joseph

Lewis's Kentucky "Orphan Brigade" came in from guard duty at Chickamauga

Station. Marcus Wright's Tennessee Brigade returned from Charleston by

rail.

To shore up his right, Bragg stripped his left over the protest of

Carter Stevenson, who still believed the real threat was against Lookout

Mountain. Bragg wisely ignored Stevenson and ordered William H. T.

Walker's division to withdraw from the base of Lookout Mountain and move

along Missionary Ridge to the far right, taking position a quarter mile

south of Tunnel Hill. To command this now critical sector, Bragg called

upon William Hardee, who turned over the extreme left to Stevenson.

Stevenson assumed command of affairs west of Chattanooga Creek

reluctantly. He sent a brigade of Jackson's division and Cummings's brigade

to close the gap in the valley that Walker's departure had opened. He

told Walthall to deploy his 1,500 Mississippians so as to picket the

mountain and retain a reserve sufficient to help Moore hold the main

line near the Cravens house.

|

MAJOR GENERAL JOHN C. BRECKINRIDGE (LC)

|

|

LIEUTENANT GENERAL WILLIAM J. HARDEE (BL)

|

Having done what he felt he could for the left and right, Bragg

turned his attention to the center of the army, which he had entrusted

to Breckinridge. After two months in front of Chattanooga, the two

generals finally realized that it might be prudent to fortify the crest

of Missionary Ridge. Breckinridge ordered Bate to begin digging at

daylight. Hardee told Anderson to do likewise. Both Hardee and

Breckinridge recalled their cannon from the valley, while their chiefs

of artillery tried in the dark to select the firing positions they

should have reconnoitered weeks earlier.

Neither Bragg, Breckinridge, nor Hardee apparently was ready to

commit himself entirely to the defense of the crest of Missionary Ridge

should an attack come against the center. Unable to decide between

holding the existing rifle pits at the foot of the ridge or withdrawing

to the unfortified crest, they settled on a peculiar compromise: Bate

and Anderson were ordered to recall half their divisions on the crest

and to leave the remainder in the rifle pits along the base. Stewart,

meanwhile, was told to stretch his already attenuated line a bit farther

to the right, so as to rest at the foot of Missionary Ridge a half mile

south of Bragg's headquarters.

Bragg may have gone to bed that night satisfied with his

dispositions. In part, his instincts had been correct. The right needed

reinforcing, and quickly. But in his zeal to do so, he had left

Stevenson with too few troops to hold the left. And although he at last

had begun to strengthen the crest of Missionary Ridge, Bragg's and

Breckinridge's decision to split the Kentuckian's corps between the top

and the base negated any advantage the high ground might offer.

Thomas was as pleased as Grant with the events of November 23. Not

only had his army proven to Grant that it could fight, but he had won a

concession from the commanding general. Hard use and rising waters had

torn apart the pontoon bridge at Brown's Ferry, stranding the last of

Sherman's units, Brigadier General Peter Osterhaus's division, in

Lookout Valley. When it became clear that Osterhaus would be unable to

cross for at least twelve hours, Grant ordered him to report to Hooker.

The brigades of Walter Whitaker and William Grose were also trapped in

Lookout Valley.

The three divisions now congregating in Lookout Valley were more

than enough for a simple diversion against the Confederates, so Grant

acceded to Thomas's demand that a more serious effort be made against

Lookout Mountain. He stopped short of giving permission for a full-scale

assault; Hooker, he cautioned, should "take the point only if his

demonstration should develop its practicability."

|

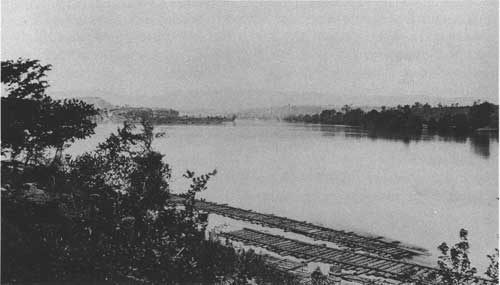

SHERMAN WAS TO CROSS THE TENNESSEE RIVER NEAR THIS POINT. (USAMHI)

|

Such subtleties were lost on Hooker. In his orders to Geary for

November 24, Hooker said nothing of a mere demonstration; Geary was to

take Lookout Mountain, plain and simple. He was to set off at dawn,

cross Lookout Creek above Wauhatchie, and march down the valley,

"sweeping every Rebel from it." Whitaker's brigade would accompany him;

Grose's brigade and Osterhaus's division would cross the creek near its

mouth. The two forces were to converge on the point of Lookout. Once he

controlled the mountain, Hooker intended to drive his united command

through Chattanooga Valley against Bragg's extreme left near

Rossville.

Sherman declined Grant's offer to delay the offensive one day more to

allow Osterhaus to rejoin his corps; Sherman was sure he could succeed

with the three divisions on hand.

During the afternoon, Sherman's troops marched from their concealed

camps to their assigned staging areas. The brigade of Brigadier General

Giles Smith was to take to the boats in North Chickamauga Creek. Joseph

Lightburn's brigade of the same division and Ewing's division were to

assemble behind the high hills opposite South Chickamauga Creek.

The operation was to begin at midnight. Giles Smith's brigade was to

float down the Tennessee, land just above South Chickamauga Creek, and

then disarm the Rebel pickets posted near its mouth. After Smith's men

disembarked, the empty boats would bring over the rest of Sherman's

force. Lightburn's brigade and John Smith's division were to entrench on

high ground along the east bank of the river, while Ewing's division was

ferried over.

Once everybody was organized on the east bank, the three divisions

would advance against the northern extreme of Missionary Ridge.

|