(click on image for a PDF version)

|

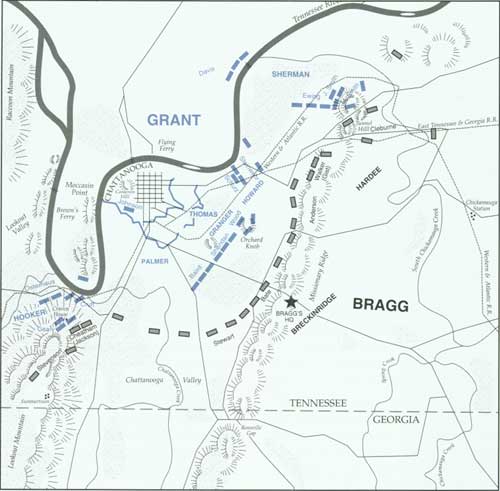

THE BATTLE OF LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN, NOVEMBER 24

Federal troops under Sherman began crossing the Tennessee River just

below the mouth of South Chickamauga Creek before dawn. That afternoon,

Sherman advanced toward the north end of Missionary Ridge to attack the

Confederate right flank but found the topography and Confederate troop

dispositions different than what had been expected. Sherman was not

successful in rolling up the Confederate right.

On the Confederate left, Federals under Hooker attacked and drove the

Confederates from the slopes of Lookout Mountain. Geary's and Cruft's

divisions swept northward toward and around the northern tip of the

mountain. Joined by Osterhaus's Division, they drove the Confederates

before them and forced the Southerners to abandon their remaining

positions on Lookout Mountain that night.

|

The crossing began on schedule, and by 6:30 A.M. Sherman had two

divisions assembled less than two miles from Missionary Ridge. A mile

and a half to the south, General Howard was preparing to send Bushbeck's

brigade north along the river road to open communications with him. And

John Smith had discovered a second, more commanding ridge 500 yards east

of the one he had fortified. He seized it without opposition. Not a

single Rebel could be seen in the fields to his front. At a minimum, a

strong reconnaissance into the woods beyond seemed in order. Yet

Sherman hesitated, unwilling to move until Ewing was up. He told Smith

to fortify the ridge, and the morning slipped quietly away.

Bragg was in the saddle shortly after daybreak. He rode north along

Missionary Ridge examining his lines with satisfaction when, through the

lifting fog, he saw, two miles across the valley, the divisions of John

Smith and Morgan Smith digging in at the mouth of South Chickamauga

Creek and Bushbeck's brigade filing north to join them.

No doubt Bragg was stunned. He had not expected a movement against

his right emanating from a point so far to the north. But even now, with

proof of Grant's intentions there before him, Bragg faltered; perhaps

Sherman's crossing was merely a feint. The measures he took during the

morning were stopgaps, reflecting an uncertainty as profound as that of

Sherman. Bragg had ample troops at hand with which to contest Sherman's

advance: Cleburne's division, reinforced by the Orphan Brigade, lay

bivouacked behind Bragg's headquarters. But Bragg told Cleburne to send

only one brigade to the far right. When Marcus Wright's brigade reached

Chickamauga Station at 8:30 A.M., Bragg ordered him to march to the

mouth of South Chickamauga Creek to "resist any enemy attempt to

cross"—a bizarre order since Sherman already had five times as many

troops over as Wright had in his brigade.

Bragg did nothing more. Only two brigades, neither within supporting

distance of the other, moved to resist an advance by three divisions,

supported by a fourth under Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis.

Bragg had handed Sherman the chance to destroy his army; the Ohioan

let it slip through his fingers. As the morning passed, he kept the two

Smiths busy digging in while waiting for Ewing to cross the river.

Howard cantered up to the head of Bushbeck's column at noon. Less

certain that he could succeed without reinforcements, Sherman

convinced Howard to leave Bushbeck with him.

|

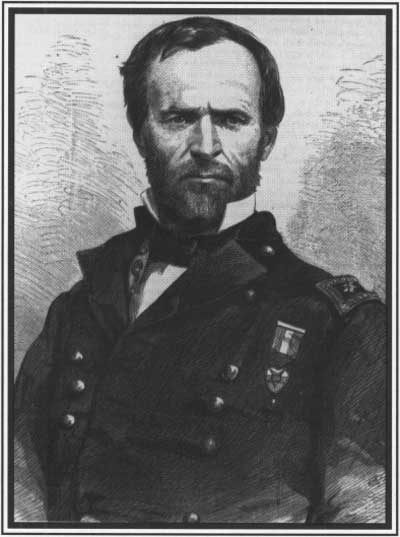

GENERAL WILLIAM T. SHERMAN (NPS)

|

At 1:30 P.M., with less than four hours of gray daylight remaining,

Sherman advanced. Less than a mile and a half of fields, forest, and

swamps stood between Sherman and the high hills at the northern extreme

of Missionary Ridge. Displaying uncommon trepidation, Sherman moved at a

snail's pace, constantly looking to his right for any sign of Rebels

bounding down from Missionary Ridge to take him in the flank.

But there was not a Confederate within two miles of Sherman's flank.

Before noon, Bragg had ridden off toward Lookout Mountain without taking

any further action to strengthen his right. Nor did Hardee act until

Sherman's massed Federals marched out into the fields, at which time he

ordered Cleburne to move his remaining three brigades with all haste

toward the right of Missionary Ridge, "near the point where the

[railroad] tunnel passes through."

The nexus of the line Hardee hoped to hold with Gist and Cleburne was

Tunnel Hill (so named by Cleburne in his report). The highest point

along the northern stretch of Missionary Ridge, Tunnel Hill rose 250

yards north of the Chattanooga and Cleveland Railroad tunnel. The next

piece of ground to the north were two detached hills that formed a

U-shaped eminence much higher than Tunnel Hill.

Cleburne had just inspected the ground around Tunnel Hill when a

courier announced that the Yankees were marching up the far slope of

the eastern hill. Cleburne ordered the Texas Brigade of Brigadier

General James Smith across Tunnel Hill and up the near slope of the

detached hill. In a ravine between the elevations, the Texans collided

with Yankee skirmishers. Smith halted on the summit of Tunnel Hill and

kept the Federals occupied while Cleburne deployed the rest of his

division. He arrayed Mark Lowrey's brigade to the left of Smith and sent

Daniel Govan to the east-west spur north of the railroad to protect

Smith's right flank and rear.

|

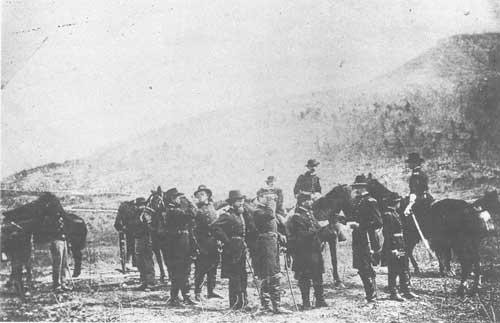

GENERAL HOOKER (SECOND FROM RIGHT, STANDING) AND STAFF IN THE SHADOW OF

LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN. (USAMHI)

|

Sherman's actions in the first crucial minutes after contact was made

were deplorable. He had made a terrible error. Through a combination of

poor maps and negligent reconnaissance, Sherman had marched from the

river convinced that the detached hills were the northern extreme of

Missionary Ridge. Not until the lead brigades of his three divisions

consolidated on the summit of the eastern bill did Sherman, looking

toward Smith's Texans drawn up on Tunnel Hill, realize his mistake.

With fifty minutes of daylight remaining—enough time to have driven

Cleburne's badly attenuated line across the railroad and probably have

forced Bragg to abandon his entire Missionary Ridge

position—Sherman chose the safe course: he ordered his men to dig

in for the night.

Fighting Joe Hooker had not the slightest doubt that he could take

Lookout Mountain. Scouts, deserters, and simple observation had given

him an excellent feel for Confederate dispositions, numerical strength,

and vulnerabilities. Hooker dismissed any direct attempt at dislodging

Stevenson from the summit; his position there would become untenable, in

any case, once Hooker swept around the bench.

Hooker and his staff worked until after midnight perfecting their

plans. Attention to detail was imperative, as Hooker's force consisted

of three divisions from three different corps, none of which had fought

together before.

At 3:00 A.M. on November 24, Geary received his orders to "cross

Lookout Creek and to assault Lookout Mountain, marching down the

valley and sweeping every rebel from it." He was to break camp at

daylight. Colonel Whitaker got his orders at the same time. He roused

his men at 4:00 A.M. for the two-hour march to Wauhatchie, where they

would join up with Geary. Colonel Grose was instructed to effect a

lodgment on the far bank of Lookout Creek near the mouth. To General

Osterhaus went a supporting role. Williamson's brigade was to protect

the artillery that Hooker was gathering on the hills near the mouth of

Lookout Creek; Woods's brigade would cover Grose and cross the creek

after him, then ascend the slope and form a junction with the left of

Geary's division as it worked its way around the mountain.

Hooker left little to chance. During the night, he brought forward

all available artillery to pulverize the Rebel pickets and cover the

advance of his own infantry. By daybreak, he had nine batteries lined up

between Light's Mill and the mouth of Lookout Creek. Two batteries from

the Army of the Cumberland lent their support from Moccasin Point; two

others set up near Chattanooga Creek.

|

UNION SOLDIERS BRIDGE LOOKOUT CREEK. (BL)

|

General Walthall had no idea that a quarter of Grant's artillery was

trained on his brigade, but he could feel the cold tingle of impending

calamity in the misty dawn air. General Moore was even more pessimistic

than Walthall: "No serious effort has been made to construct defensive

works for our forces on the mountain."

The man in overall command, Carter Stevenson, could offer his

subordinates little. He was unfamiliar with the ground and was not even

sure that Bragg really wanted him to stay on the mountain.

Dawn came at 6:30 A.M. High water and a fast current delayed Geary's

crossing of Lookout Creek until 8:30 A.M. The fog had thickened,

observed Geary with satisfaction: "Drifting clouds enveloped the whole

ridge of the mountain top, and heavy mists and fogs obscured the slope

from lengthened vision."

A little after 9:30 A.M., the bugles sounded "Forward" and

Geary's skirmishers disappeared into the fog and timber. For nearly an

hour the Federals slipped and stumbled along the craggy western slope of

Lookout.

|

Colonel George Cobham's brigade filed across a footbridge over

Lookout Creek first. Next over was Colonel David Ireland, whose brigade

faced to the front midway up the slope to form the center of Geary's

line of battle. Colonel Charles Candy's brigade crossed the creek next

and extended Geary's left down to the base of the mountain. Walter

Whitaker brought his brigade over Lookout Creek last and formed 300

yards to the rear of Geary.

A little after 9:30 A.M., the bugles sounded "Forward" and Geary's

skirmishers disappeared into the fog and timber. For nearly an hour the

Federals slipped and stumbled along the craggy western slope of Lookout.

Finally, at 10:30 A.M., the rattle of musketry from the skirmish line

announced that contact had been made. Geary's skirmishers had struck

Walthall's pickets one mile southwest of the point. The Rebels held on,

but their line was stretched far too thin to offer prolonged resistance.

Geary's main line came up without much trouble, and the pressure on the

Mississippians became unbearable. As the Federals closed to within a few

yards, the Rebels broke. Dozens were hit, and scores more

surrendered.

|

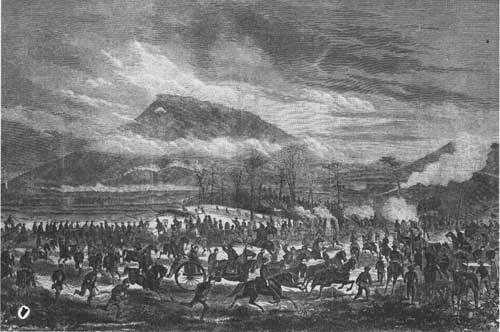

THE BATTLE OF LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN, THE SCENE FROM LOOKOUT VALLEY

ILLUSTRATION BY THEODORE R. DAVIS. (LC)

|

|

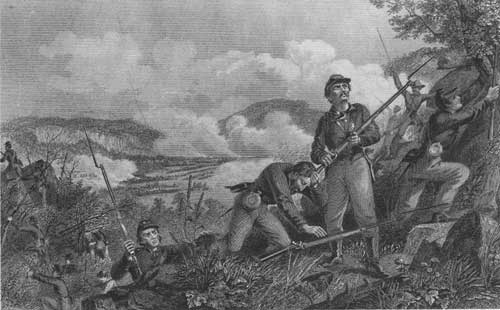

UNION SOLDIERS CLIMBING THE SLOPES OF LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN. (LC)

|

As Geary's line came in sight and the Rebel pickets began trickling

from their breastworks, Hooker ordered his artillery to saturate the

enemy's line of retreat along the mountainside. Hooker's intentions were

good but, up in the dusky forest toward which his cannoneers trained

their pieces, the opposing lines were on top of one another. Smoke and

fog hid the action from those in the valley, making the aim of the

artillerymen uncertain at best.

About 11:30 A.M., the wild Yankee pursuit came to an abrupt halt 300

yards southwest of the point of Lookout Mountain when Ireland and Cobham

ran into Walthall's two-regiment reserve, posted between the base of

the cliff and the Cravens house. Though badly outnumbered, the

Mississippians gave a good account of themselves, throwing back

Ireland's first attempt at storming their works.

With Geary and his staff on foot far to the rear, Ireland and Cobham

acted on their own to meet this unexpected resistance. Outnumbered four

to one and outflanked on both the right and left, Walthall's second

line of resistance disintegrated. Walthall tried to rally the men, but

few paid him any attention. All order was lost as the Mississippians

spilled rearward, past Walthall, around the point of the mountain, and

back toward the Cravens house.

At 12:10 P.M. Ireland and Cobham rounded the point of Lookout

Mountain and drove eastward along the bench toward the Cravens

house.

The Federals kept on past the Cravens house after Walthall's

survivors who were disappearing into the fog. Uncertain of what lurked

in the mist-shrouded trees beyond the Cravens place, Ireland's New

Yorkers wheeled to the right and trod southeastward along the slope. Off

to their left were Chattanooga Valley and the entrenchments of the Army

of the Cumberland.

Geary's appearance below the point of Lookout Mountain at noon was

the signal for Hooker to set in motion the brigades of Charles Woods

and William Grose, which were poised on the west bank of Lookout Creek,

ready to cross a footbridge. While Cobham and Ireland cleared the upper

reaches of the mountain, Candy's brigade swept the ground between the

base of Lookout Mountain and the east bank of the creek.

Shortly before noon, Candy passed through the marshy field opposite

the footbridge, clearing the way for Woods and Grose. Woods advanced

eastward, while Grose ascended the slope. The belated advance of Woods

and Grose spelled doom for the last of Walthall's regiments. Crouched

behind the railroad embankment near the turnpike bridge, the

Thirty-fourth Mississippi was cut off from the forces on the bench by

the Federal crossing, and virtually the entire regiment surrendered.

With them were 200 men from Moore's picket line, taken from behind by

Woods.

|

AN 1889 LITHOGRAPH OF THE BATTLE OF LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN. (LC)

|

General Moore caught a glimpse of his picket line withering, but he

had more pressing concerns on the bench, where the remainder of his

brigade stood, 400 yards south of the Cravens house. Ninety minutes had

passed before Moore received an answer from Mudwall Jackson to a 9:30

A.M. inquiry asking where he should deploy his brigade. Jackson was

incredulous: Did Moore not recall the plan of the night before to defend

the line at the Cravens house? Moore was reluctant to move. He applied

to Walthall for reassurances that the Mississippian would be on his left

when Moore brought his own brigade forward. Walthall could not

answer—he was being overwhelmed too quickly to promise

anything.

There was bungling aplenty among the Confederate commanders on

Lookout Mountain, but no one displayed greater negligence than Jackson.

He remained glued to his headquarters, a mile behind the line he had

been charged to defend. Jackson lacked even the presence of mind to call

for reinforcements; Stevenson had to offer them. When the roll of rifle

volleys announced Walthall's clash with Geary at 12:30 P.M., Stevenson

ordered Brigadier General Edmund Pettus to take three of his regiments

down from the summit and report to Jackson.

|

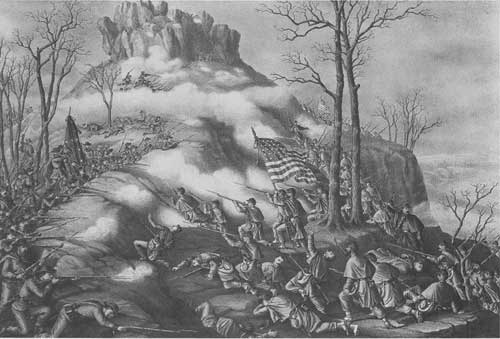

STORMING AND CAPTURE OF LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN IS THE TITLE OF THIS

PERIOD LITHOGRAPH. (LC)

|

|

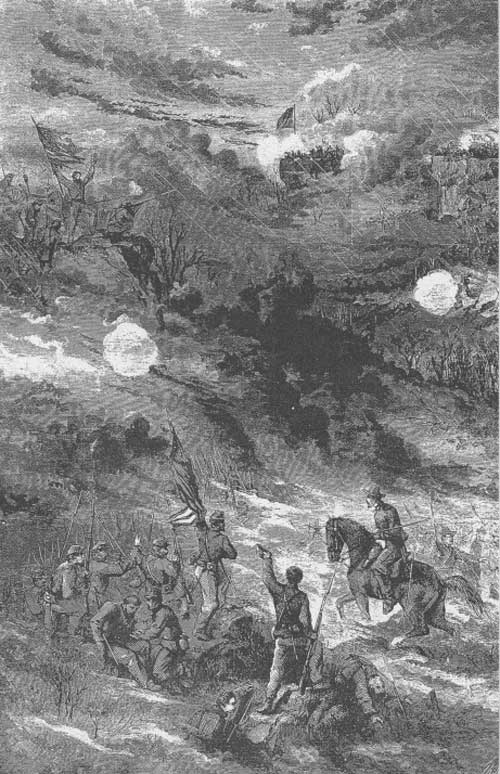

THIS ILLUSTRATION FROM HARPER'S WEEKLY WAS TITLED GENERAL

HOOKER FIGHTING AMONG THE CLOUDS. (LC)

|

By then, Moore was moving. As they neared the Cravens yard, his

Alabamians met the remnants of Walthall's brigade rushing to the rear.

Instead of finding the stone wall to their front, Moore and his men

glimpsed Ireland's New Yorkers through the drizzle. Both sides opened

fire at a range of 100 yards. The thick mist disguised Moore's small

numbers, and the New Yorkers retreated beyond the stone wall. Moore

settled his men in behind it and in the rifle pits it screened.

Moore put up a good fight. He stretched his 1,000 men as thin as he

felt he could behind the entrenchments, from the Cravens house down the

mountainside, and awaited the Yankee counterattack.

It was slow in coming. Ireland's men were dazed and tired. They lay

down along the western fringe of the Cravens yard, protected from

Moore's fire by the fog and a dip in the ground.

Whitaker's brigade arrived behind Ireland's stalled line a little

after 1:00 P.M. His men were spoiling for a fight, and they swept over

the supine New Yorkers and into the yard.

Moore was woefully outnumbered—Whitaker alone had 500 more men

than he did—and the odds were getting worse. To Moore's right

front, Candy's brigade was clambering up the mountainside to regain its

connection with Ireland's left. To Candy's left and rear were the

brigades of Woods and Grose. Although not yet near enough to attack

Moore, the Federal line clearly extended far beyond his right flank: "It

became evident we must either fall back or be surrounded and captured,"

surmised Moore. He chose the former course and withdrew most of his

command off in good order southward, toward the Summertown road.

Their front clear, Whitaker's men whooped and hopped over the stone

wall. Whitaker wanted to stop there, but his men surged past him.

Ireland was on the move again as well, to the left and rear of

Whitaker.

Whitaker was not alone in wanting to call a halt. As the weather

worsened, Hooker was content merely to see Geary round the bench.

Fearful that the enemy might be reinforced and his own lines disordered

by the fog and rugged ground, he had sent word to Geary to halt for the

day before reaching the Cravens house. But Geary was on foot and too far

behind his troops to stop them, and so, as Hooker put it, "fired by

success, with a flying, panic-stricken enemy before them, they pressed

impetuously forward."

The fog slowed them, giving Moore the chance to get away and Walthall

time to form a scratch line 300 yards south of the Cravens house with

the 600 men left to him. Crouching behind boulders and fallen trees,

they kept up enough of a racket to halt Whitaker. Thirty minutes later,

they heard the tramp of Pettus's column coming up behind them.

Pettus filed his three Alabama regiments off the Cravens house road

and into line. Marching forward, they relieved Walthall's band a little

after 2:00 P.M. and fell in behind a natural breastwork of limestone

outcrop. Moore regrouped on their right.

Pettus's line was engaged instantly. For the rest of the afternoon

and well into the night, the six Alabama regiments of Pettus and Moore

traded volleys with an invisible foe. In some places, the two lines were

just thirty yards apart. At points of collision, the smoke of battle

hung in blue sheets among the naked branches of the trees until beaten

into nothing by the falling rain. The fighting degenerated into a series

of weak, half-blind punches and counterpunches in the foggy twilight.

The racket was tremendous, the lead expended prodigious, but hardly

anyone was hurt.

|

A MODERN-DAY VIEW FROM ATOP LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN. (NPS)

|

Fighting Joe Hooker's confidence returned an hour before sunset.

Although he had told Geary earlier to dig in for the night along the

eastern slope, Hooker now announced to Grant his intention to descend

into Chattanooga Valley as soon as the fog lifted. "In all probability

the enemy will evacuate tonight. His line of retreat is seriously

threatened by my troops."

The fog never lifted, so Hooker was not put to the test. Hooker may

have embarrassed himself with his blustering, but he had correctly

guessed Bragg's intentions.

Down in Chattanooga Valley, Bragg was furious—at a loss to

understand how Stevenson, with six brigades at his disposal, could have

failed to hold the bench and slope of Lookout Mountain. Now Stevenson

was begging for another brigade in order to avert total defeat. Bragg

granted the request conditionally—the brigade sent over was to be

used to cover Stevenson's withdrawal. Bragg would do no more. To him,

the battle effectively was over and Lookout Mountain lost. At 2:30 P.M.,

he instructed Stevenson to withdraw from the mountain to the east side

of Chattanooga Creek.

As Bragg left the timing and manner of the withdrawal to his

discretion, Stevenson decided not to risk breaking contact with the

Federals on the eastern slope until the troops on the summit made good

their escape. Walthall, Pettus, and Moore would have to hold on—all

night if necessary—to keep open the Summertown road, the only means

of egress into Chattanooga Valley.

The senseless firing on the mountainside continued, alternately

sputtering and swelling. Union regiments were moved in and out of the

line during the night so that everyone on the mountain eventually had a

hand in the fight.

Down in the valley, near Chattanooga Creek, Breckinridge, Stevenson,

Jackson, and the recently returned Ben Franklin Cheatham met at the

Gillespie house at 8:00 P.M. Cheatham was livid—Jackson had nearly

destroyed two of his brigades. Breckinridge yielded the floor and left,

and Cheatham took charge of the meeting. He concluded the business

rapidly. Cheatham told Stevenson to remove his own and Cheatham's

divisions from the west side of Chattanooga Creek and stand by on the

east bank while Cheatham searched out Bragg for further orders.

Bragg, meanwhile, was absorbed in a meeting of his own. Breckinridge

had ridden directly from the Gillespie house to army headquarters. There

he, Bragg, and Hardee fell into a largely futile discussion of how they

might recoup their losses of the day. The situation was grim. With

Lookout Mountain lost and Sherman menacing Tunnel Hill, both flanks were

in danger. Another setback on either flank threatened the whole army.

Outnumbered two to one, Bragg barely had enough troops to reinforce one

flank. Finally, South Chickamauga Creek was swelling rapidly from the

steady rains, jeopardizing Bragg's line of retreat.

Bragg had no idea what to do. He turned to Hardee and Breckinridge

for advice. Hardee was all for conceding Chattanooga. The army, he said,

should cut its losses and withdraw across South Chickamauga Creek.

Breckinridge disagreed vehemently. There was no time that night for such

a move, which certainly would be discovered. In falling back,

Breckinridge continued, the army would be subject to defeat in detail

after daybreak. Furthermore, he said, Missionary Ridge was an

inherently strong position.

Bragg endorsed Breckinridge's petition to hold fast on Missionary

Ridge. Hardee argued a bit longer for a withdrawal but finally

relented. He convinced himself that the natural strength of Missionary

Ridge was sufficient to deter a direct assault against the center or

left. Hardee decided that the real threat would come from Sherman

against the right flank, which he argued was also the most vulnerable

part of the Confederate line.

Bragg agreed. He promised to send Cheatham and Stevenson to reinforce

the right during the night. Hardee would command the four divisions on

the right—those of Cleburne, Walker, Stevenson, and Cheatham.

Anderson's division was too far to the left for Hardee to devote

adequate attention both to it and to the expected fight around Tunnel

Hill. Consequently, it was reassigned to Breckinridge. The Kentuckian

was to order Stewart up from Chattanooga Valley and onto the ridge at

once; responsibility for guarding the extreme left at Rossville Gap

would rest with Stewart.

|

A POST-BATTLE PHOTOGRAPH OF FEDERAL TROOPS EXAMINING THE BATTLEFIELD AND

THE RUINS OF THE CRAVENS HOUSE HALFWAY UP LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN. (THE WESTERN

RESERVE HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

|