(click on image for a PDF version)

|

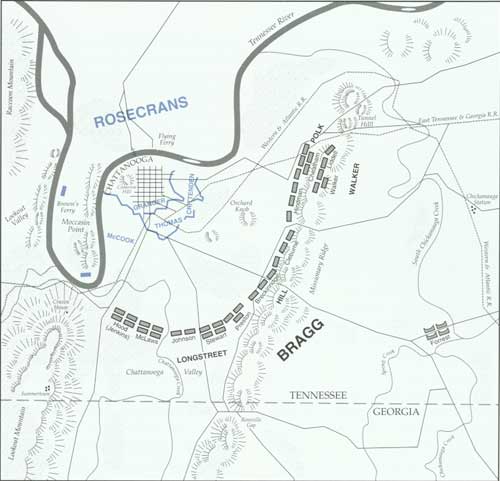

BRAGG LAYS SIEGE TO CHATTANOOGA, SEPTEMBER 24, 1863

Rosecrans has withdrawn the Army of the Cumberland into Chattanooga.

Houses, buildings, and trees on the edge of the city were removed for

construction material and to create fields of fire. Federal forces

stationed on Moccasin Point guarded the approaches into the city from

Lookout Mountain and Lookout Valley.

Bragg deployed the Army of Tennessee in positions along the base of

Missionary Ridge, across Chattanooga Valley, and to the northern toe of

Lookout Mountain. Longstreet's forces soon occupied Lookout Mountain and

extended a small number of troops into Lookout Valley closing off all

the Federal supply routes into Chattanooga but the northern one.

|

Grant arrived at Chattanooga on October 23. General Thomas was ready

with a formal briefing. He made a few general remarks, then gave the

floor over to Major General William Farrar "Baldy" Smith, a recent

arrival to the Army of the Cumberland whom Rosecrans had made chief

engineer of the Department of the Cumberland. Before being relieved,

Rosecrans had devised a plan for reopening the river supply route to

Bridgeport, which would dramatically cut both the time and risk to Union

supply efforts. Fundamental to Rosecrans's plan was the conviction that

General Joseph Hooker must move from Bridgeport with his force from the

Army of the Potomac to occupy Lookout Valley and seize the passes of

Lookout Mountain before a bridge could be thrown across the Tennessee

River from Moccasin Point, for the last leg of the journey into

Chattanooga.

Reconnoitering possible bridge sites the week before, Smith had come

upon a spot on the western side of Moccasin Point known locally as

Brown's Ferry that struck him as ideal. Its tactical importance was

obvious. The only road along that stretch of the river cut through a gap

in a chain of foothills that lined the shore opposite Brown's Ferry.

More significant, less than a quarter mile beyond the gap the road

turned south and became the primary wagon road through Lookout Valley as

far south as Wauhatchie, where it forked, meeting a road that ran west

all the way to Kelley's Ferry. The gap itself struck Smith as an ideal

crossing site. Narrow but deep, it split the foothills just above the

level of the river. Only a few Rebel picket posts were in evidence.

|

GENERAL ROSECRANS (SEATED FOURTH FROM LEFT) AND STAFF. (THE WESTERN

RESERVE HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

Smith stood before a large map of the region and spoke passionately

of his plan to Grant. Grant was impressed. He approved Smith's scheme

for opening the supply route now known as the cracker line and delegated

its execution to Thomas and Smith.

The two worked quickly. Thomas immediately wired Hooker detailed

marching orders. He was to detach Major General Henry Slocum with one

division of the Twelfth Corps to guard the rail line from Murfreesboro

to Bridgeport. With the remaining division, under Brigadier General John

Geary, and Howard's Eleventh Corps, Hooker was to cross the Tennessee

River at Bridgeport and move as rapidly as possible to Lookout

Valley.

Hooker was slow in starting. His command was scattered across the

countryside north of Bridgeport. With the roads still miserable

quagmires from the rains, it would be a day, perhaps two, before be

would be ready to move.

Grant was annoyed but not alarmed. He no longer shared Smith's

conviction that Hooker's thrust into Lookout Valley must occur

simultaneously. As he now saw things, the capture of Brown's Ferry and

the hills flanking it would permit him to forestall the sort of Rebel

concentration in Lookout Valley designed to drive back Hooker that

Smith feared. A lodgment at Brown's Ferry would enable Grant to throw a

force against the right flank of any Rebel units that ventured into the

valley.

As Thomas kept an eye on Hooker's progress, Smith set about

organizing the assault on Brown's Ferry. One brigade would travel

downriver under the cover of darkness from Chattanooga to Brown's Ferry;

there the troops were to disembark and capture the gorge and hills on

the west bank. The hazards were clear: the men would be floating targets

for nine miles. Rebel batteries atop Lookout might reduce the flotilla

to splinters. Smith judged the reward worth the risk.

|

AN ILLUSTRATION BY C. S. REINHART OF GRANT AT THOMAS'S HEADQUARTERS.

SHOWN LEFT TO RIGHT ARE GENERAL RAWLINS, CHARLES A. DANA, GENERAL

WILSON, GENERAL W. E. SMITH, GENERAL GRANT, GENERAL THOMAS, AND CAPTAIN

PORTER. (NPS)

|

Meanwhile, a second brigade and the artillery were to march across

Moccasin Point to the ferry in time to cross the river in support of the

assaulting force.

Smith chose his brigade wisely. For the river-borne force he selected

the command of Brigadier General William Hazen, a proven fighter whose

daring was exceeded only by his ambition. To lead the supporting

brigade, Smith called on the "Mad Russian," Brigadier General John

Turchin.

No one at Bragg's headquarters atop Missionary Ridge had an inkling

of what was about to unfold over in Lookout Valley. And they were not

going to find out, if matters were left to General Longstreet. Bragg had

accurate information on Sherman's progress across northern Mississippi,

thanks to Stephen Dill Lee's cavalry. Closer to home, he learned from

scouts on October 25 that Hooker was preparing to cross the river at

Bridgeport. That same day, Major James Austin's Ninth Kentucky Cavalry

came upon Yankee engineers rebuilding the railroad trestles in the gorge

of Running Water Creek.

Austin's report worried Bragg. He ordered Longstreet to make a close

reconnaissance toward Bridgeport and to protect his left flank,

presumably by moving additional units into Lookout Valley.

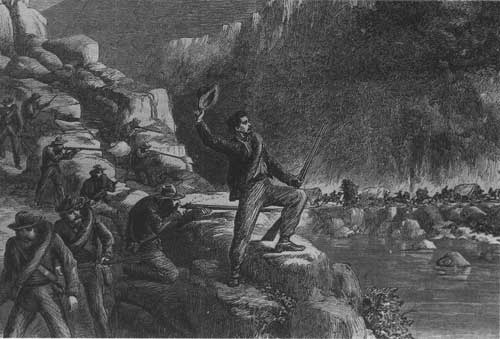

Nothing happened; Longstreet simply laid aside Bragg's instructions.

Still smarting over President Davis's decision to retain Bragg,

Longstreet probably reasoned that, if he could not command the army, he

might at least run his corps as he saw fit.

In truth, Longstreet was doing a poor job at even that. After

committing Evander Law's brigade to the defense of Lookout Valley in

early October, Longstreet gave no further thought to that

all-important avenue of approach.

|

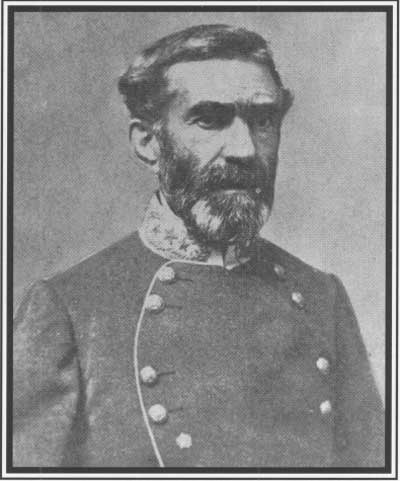

GENERAL BRAXTON BRAGG (USAMHI)

|

Matters there were worse than Bragg could have imagined. Law went on

a leave of absence. For reasons known only to himself, Brigadier General

Micah Jenkins recalled Law's three reserve regiments to the east side of

Lookout Mountain on October 25, leaving only Colonel William Oates with

the Fifteenth Alabama near Brown's Ferry and the Fourth Alabama

scattered northward along the bank of the river.

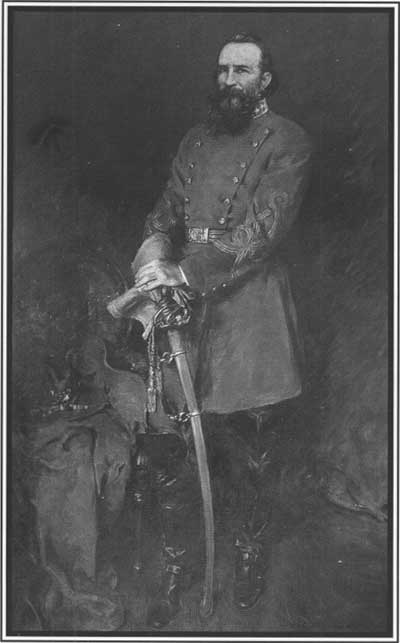

Shortly after midnight on October 26, the soldiers of Hazen's brigade

were assembled at the embarkation point. The moon sank below the

horizon. A heavy mist rolled into the valley, blanketing the river. Only

then did company officers learn of their destination.

All was ready at 3:00 A.M. on October 27. The boats glided past the

looming point of Lookout Mountain. At 4:30 A.M. the lead flatboat

thudded against the riverbank at Brown's Ferry. Ten minutes after the

last pontoon landed, Brown's Ferry was in Federal hands. Out in the

valley beyond the ferry, Colonel Oates was shaken awake as the first light

of dawn touched the hilltops. A frightened private from the scattered

picket force told him of the Yankee crossing.

|

HAZEN'S MEN FLOAT DOWN THE TENNESSEE RIVER NEAR BROWN'S FERRY. (NPS)

|

|

PORTRAIT OF GENERAL JAMES LONGSTREET. (NPS)

|

The cracking of axes against trees told Oates where to find the

Federals, but in the dark he could not guess their numbers. He attacked

nonetheless, and his Alabamians were slaughtered. Oates himself fell

with a bullet through the arm. Carried to a house near the mouth of

Lookout Creek, Oates met General Law at the head of his three reserve

regiments. "I told him that he was too late, in my opinion, to

accomplish anything; that a heavy force had already crossed the river,"

recalled Oates. Thoroughly disgusted, Law placed his brigade astride the

road over Lookout Mountain and reported the disaster to Longstreet.

Brown's Ferry was a scant three miles from Longstreet's headquarters.

But it may as well have been in another country, for all the attention

Longstreet paid it. Moccasin Point and Lookout Mountain not only blocked

the general's view of the ferry but also blinded him to its tactical

significance. He greeted Law's frantic dispatch announcing the fall of

Brown's Ferry with an indifference that amounted to dereliction of duty.

Confident that the Yankee crossing was merely a feint to cover a Federal

approach along the length of Lookout Mountain, beginning near Trenton,

Longstreet tucked away Law's message and gave the matter no further

thought; nor did he bother to inform Bragg of what had happened.

Longstreet's odd notion of a Federal threat from the south was the

product of his imagination. He had neglected to reconnoiter toward

Bridgeport as Bragg ordered, nor did he have scouts out in the direction

of Trenton to test his assumption.

Up on Missionary Ridge, Bragg exploded with rage when he learned that

Brown's Ferry had fallen. He rued ever having given Longstreet so much

responsibility and sent word to him to retake the lost ground at

once.

Again Longstreet did nothing. He let the day slip away and permitted

Smith's Federals to consolidate their bridgehead unmolested. He argued

with Bragg well into the night of October 27 that the enemy was moving

on Trenton in force. Bragg was unconvinced. To prevent further

misunderstanding, Bragg met Longstreet atop Lookout Mountain the next

morning. Their discussion was cut short by a startling discovery: a long

and powerful Federal column had emerged from the gorge of Running Water

Creek and was marching down Lookout Valley. Fourteen hundred feet below

and less than a mile west from where Bragg and Longstreet stood was the

head of Hooker's column, closing on the valley hamlet of Wauhatchie.

Hooker made good time down the valley, reaching Brown's Ferry at 3:45

P.M. The joy of Hazen's and Turchin's men, on seeing the easterners'

approach, "was beyond description," said an officer in Hazen's

brigade.

With the wagon road to Bridgeport open and the river clear to

Kelley's Ferry, Thomas and his staff worked late into the night to see

to it that rations would begin to flow over the Cracker Line into

Chattanooga. Difficulties remained, but Thomas felt confident enough to

wire Halleck that night that he hoped "in a few days to be pretty well

supplied."

|

LONGSTREET'S SHARPSHOOTERS FIRE UPON A FEDERAL WAGON TRAIN DURING AN

OCTOBER SKIRMISH. (HARPER'S PICTORIAL HISTORY OF THE GREAT

REBELLION)

|

|

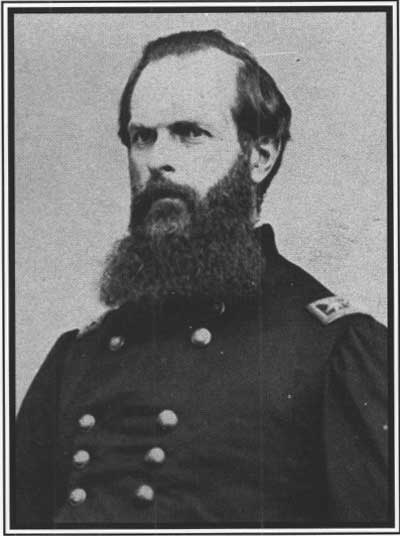

BRIGADIER GENERAL JOHN GEARY (LC)

|

Of course, that was contingent upon Hooker and Smith holding open the

wagon road across the northern stretch of Lookout Valley, which linked

Brown's Ferry with Kelley's Ferry. For the master of Brown's Ferry, that

should have been an easy task, but Smith was deeply troubled. Hooker

had not taken up any military position but directed the commanders to

find good cover for the troops and encamp for the night. The divisions

of Adolph von Steinwehr and Carl Schurz bivouacked haphazardly in the

fields on either side of the road, a half-mile above Brown's Ferry.

Hooker's most egregious error was his placement of John Geary's tiny

division, down to just 1,500 men, at Wauhatchie. There were two viable

approaches across the valley to Kelley's Ferry, one the wagon road over

the northern base of Lookout Mountain near the river, the other a

country lane that left the valley road at Wauhatchie and wound its way

northwest toward a gorge in Raccoon Mountain that ended at the ferry.

Hooker was confident that Howard could intercept any force attempting

to move against Kelley's Ferry by way of the northern approach but

worried that the Rebels might use the road from Wauhatchie if it were

left undefended. Consequently, he ordered Geary to halt there for the

night.

Geary obeyed the order with grave misgivings. He saw the danger of

his exposed position under the heights of Lookout, from which the

Confederates could watch his every move. As night fell and a brilliant,

nearly full moon rose over Lookout Valley, Geary ordered his two brigade

commanders, Brigade General George Sears Greene and Colonel George A.

Cobham, Jr., to bivouac their commands upon their arms. With the

infantry were four guns of Knap's Pennsylvania battery, one section of

which was led by Geary's son, Lieutenant Edward Geary.

The men camped along the northern fringe of a forest 300 yards north

of where the Trenton Railroad joined the Nashville and Chattanooga line.

A broad corn field lay beyond the forest. On the southern edge of the

field stood a log cabin belonging to the Rowden family. Northeast of the

cabin was a low knoll. The railroad tracks, which ran upon an

embankment, skirted the knoll. Fifty yards south of the cabin rose

another knoll; atop it Geary planted Knap's battery. The country lane to

Kelley's Ferry marked the northern limit of the Rowden Field, and a

swamp bordered it on the west.

Geary spread his picket posts so as to encircle the division bivouac,

pushing sentinels as far as Lookout Creek, and waited.

|

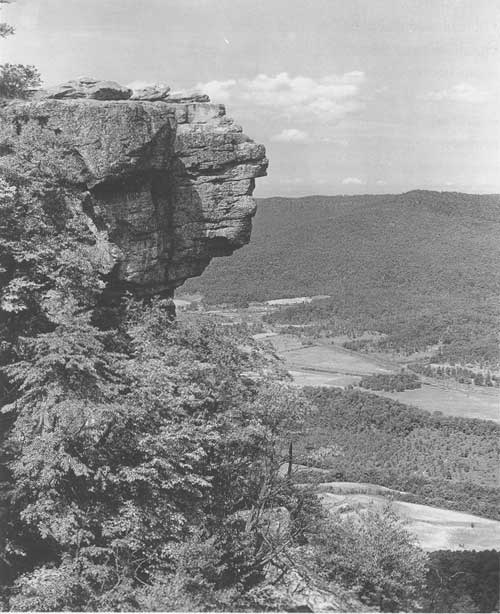

LONGSTREET USED SUNSET ROCK ON LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN AS AN OBSERVATION AREA

PRIOR TO THE BATTLE OF WAUHATCHIE. (NPS)

|

There had been no meeting of the minds between Bragg and Longstreet

during their morning encounter atop Lookout Mountain. Watching Hooker

move down the valley, Bragg demanded that Longstreet attack Brown's

Ferry, even though it would mean taking on two more Yankee divisions.

Longstreet begged leave to attack by moonlight that night. Bragg

agreed.

No sooner had Bragg left than Longstreet lost interest in the attack.

He failed to tell Law, whose brigade, being nearest the enemy, would

play a leading role in any assault, that he should prepare for action at

dusk. Longstreet probably would have ignored Bragg's order, had it not

been for Hooker's cavalier deployment of Geary's division. Loitering

about Sunset Rock in the waning of the late autumn afternoon, Longstreet

was startled to see what he assessed to be the Yankee rear guard,

burdened with a large wagon train, stop and bivouac "immediately in

front of the point upon which we stood."

Longstreet conceived a plan of his own. He would indeed attack: not

the Federal main body at Brown's Ferry, as Bragg had demanded, but the

isolated force at Wauhatchie. He told Micah Jenkins to bring his

remaining brigades over Lookout Mountain as soon as it was dark. Pleased

at the prospect of offensive action of any sort, Bragg consented to

Longstreet's plan.

Longstreet's planning was erratic—he failed to give either

Jenkins or Law clear orders—and his choice of units to carry out

the operation was foolish. Between Jenkins and Law there existed a nasty

rivalry that had started when Jenkins was given permanent command of

Hood's division over Law after Chickamauga.

The two brigadier generals met shortly after nightfall. Jenkins

briefed Law on what was expected of him. With his own brigade, commanded

by Colonel James Sheffield, and that of Brigadier General James

Robertson, Law was to hold the high ground east of the Brown's Ferry

road and slash at the flank of any Yankee column that might venture

south to relieve the force at Wauhatchie, which Jenkins would attack

with his brigade under Colonel John Bratton. Brigadier General Henry

Benning's Georgia Brigade was to be held on Law's left, to reinforce

Bratton as needed.

Law formed his line of battle on the designated hill and began to

fortify it. At 10:00 P.M., Robertson reported with his brigade. Law told

him to hold his command in a field behind the hill, both to act as a

reserve and to watch the gap that existed between Law's right and the

river.

It was nearly midnight before Bratton crossed Lookout Creek. Long,

dark clouds rolled over the valley, blanketing the moon and cutting

visibility to less than one hundred yards. Bratton's South Carolinians

stepped off gaily, believing that they were going out to capture a

lightly guarded wagon train. A few minutes after midnight, Bratton's

skirmishers collided with Geary's pickets near the creek, overrunning

the outpost and driving south along the Brown's Ferry road.

|

GEARY'S FEDERAL TROOPS HOLD THEIR GROUND AGAINST THE CONFEDERATE ATTACK

AT WAUHATCHIE IN THIS PAINTING DY WILLIAM TRAVIS. (SMITHSONIAN

INSTITUTION)

|

|

THIS HOUSE IN CHATTANOOGA SERVED AS THOMAS'S HEADQUARTERS. (LC)

|

In Geary's camp, bedlam reigned. "The night was still and chilly and

the men, roused suddenly from coveted sleep, were dazed and trembled

from chilliness and the nervous strain induced by the unexpected

situation," said a New Yorker. "They were thoroughly surprised and

unprepared for an enemy whose presence they could not divine."

Geary's division deployed in a "V" with the base pointing north. Both

sides fought with a brutal tenacity, the blackness of the night feeding

their fear. Colonel Bratton tried to maneuver his brigade so as to

outflank his numerically equal foe. He also spread his command out in a

"V" which opened toward the Federals.

Three of Bratton's regiments hit Geary's line head-on. They came

within a stone's throw of the Federal ranks before grinding to a halt on

the north side of the Rowden field. Frustrated in their advance, the

South Carolinians took aim at the gunners and horses of Knap's battery,

atop the knoll only 200 yards away.

Their aim was good. Lieutenant Geary bent down to sight a cannon. He

stood up again, yelled "Fire," then fell dead with a bullet between the

eyes. Twenty-two of forty-eight artillerymen were shot down, along with

thirty-seven of their forty-eight horses.

Although Bratton made no headway against Geary's flanks, he gave no

thought to breaking off the attack. He reported, "The enemy line of fire

at this time was not more than 300 to 400 yards in length . . . the

sparkling fire making a splendid pyrotechnic display."

And by 3:00 A.M., that fire was weakening. Fumbling for their last

cartridges, the men on the line prepared for the worst. "It looked as if

the engagement would end in a hand-to-hand struggle," speculated a

Pennsylvanian.

He was wrong. At the instant his confidence surged to an apex,

Bratton was handed a note from Jenkins ordering him to withdraw. A

strong Yankee column was pushing up the valley two miles in his rear,

the message warned. It had engaged Law and now threatened to cut off

Bratton from the bridge over Lookout Creek. Bratton stuffed the note in

his pocket and recalled his troops.

|

KNAP'S PENNSYLVANIA BATTERY, SHOWN HERE AFTER FIGHTING AT ANTIETAM,

SUFFERED HEAVY LOSSES AT WAUHATCHIE. (LC)

|

|

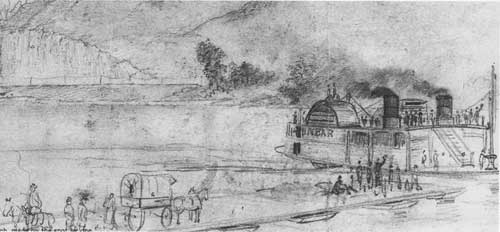

A DRAWING FROM FRANK LESLIE'S ILLUSTRATED NEWSPAPER OF A FEDERAL

STEAMBOAT PASSING THROUGH AN OPENING IN THE PONTOON BRIDGE AT BROWN'S

FERRY. (NY PUBLIC LIBRARY PRINT COLLECTION)

|

The Federal column consisted of Hooker's tired easterners, awakened

by the first volleys from Bratton's advance against Geary. Startled by

the firing, Hooker was in mortal terror that his disregard for Geary's

exposed position might cost him the division, and he told Carl Schurz to

"double-quick" his men to Wauhatchie. Unexpected opposition from Law's

brigade as the Federals marched past its position forced them to halt

and deploy at 2:30 A.M. Geary already had been fighting for two

hours.

Convinced that Geary was nearly annihilated, Hooker now confronted

the likelihood that the Rebels also were trying to wedge their way

between his relieving column and Brown's Ferry. Believing it imperative

that Law's hill be secured, Hooker abandoned his resolve to assist Geary

with his entire command and ordered an attack on the hill. Under a

mistaken impression that Schurz was leading the march (he actually had

fallen behind Steinwehr) and thus well on his way to Geary, Hooker threw

Orland Smith's brigade of Steinwehr's division into the assault. When

Law repelled Smith handily, Hooker and his lieutenants were thrown into

a frenzy. Troop commanders pushed on or hesitated, according to their

natures. Bewildered staff officers, separated from their superiors,

issued orders recklessly. The valley road and fields to the west

thronged with troops moving about without a purpose. Only Tyndale's

brigade, with Carl Schurz leading it, kept on toward Wauhatchie—one

brigade of the original two divisions Hooker had dispatched to

Geary.

Soon even that force was distracted from its purpose. Coming up

opposite the first rise south of Law's hill, Schurz was told by an

officer from Hooker's staff to take it. Schurz questioned the wisdom of

the order but halted and deployed Tyndale. At this point, General Howard

ceased to be a player in the dark comedy. Perhaps feeling superfluous, he

begged Hooker to allow him to continue on his own. Hooker agreed, and

Howard rode off with his cavalry escort.

|

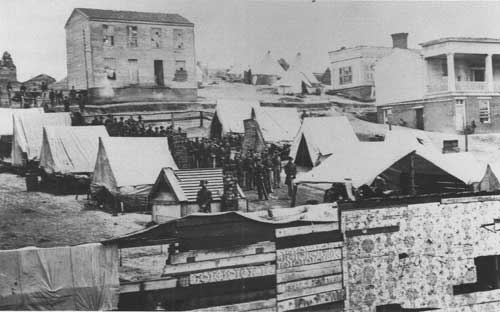

FEDERAL TROOPS CAMPED INSIDE CHATTANOOGA AFTER THE BATTLE. (WESTERN

RESERVE HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

The only officer above the rank of regimental commander who kept his

head was Colonel Smith, who charged the hill again, despite being badly

outnumbered. Smith's second assault certainly would have failed had Law

not then given up the contest as lost. Staff officers reported that

Bratton had been repelled and was falling back over Lookout Creek.

Concluding that a further sacrifice of lives would be useless, Law

withdrew from the hill just as Smith's men lurched toward his works.

The carrying of the hill did little to settle Hooker's nerves. It was

4:30 A.M., and the firing from Wauhatchie had died away. Hooker told

Schurz to hurry on to Geary's camp—on the assumption it still

existed.

General Howard and his escort entered Geary's lines at 4:00 A.M.

Geary had lost 216 men, including his son. Bratton lost 356. It had been

a senseless affair. Hooker had left Geary exposed in the valley and

invited an attack to no good end; Grant was disgusted and of a mind to

relieve Hooker. Longstreet had accepted Howard's challenge with a force

far too small to offer a reasonable chance of success.

Only the Federals had anything to be thankful for. As General Howard

wrote his wife: "God has been good and sparing and given us the victory

and we have opened the river from Bridgeport almost to Chattanooga."

Grant too would concede as much. "The cracker line" was opened, he later

wrote, and "never afterward disturbed."

Bragg was less charitable with troublesome subordinates than Grant.

After the Wauhatchie fiasco, he looked about for a means to rid himself

of Longstreet.

President Davis provided it. Two days earlier, he had reminded Bragg

that "the period most favorable for actual operations is rapidly passing

away." He suggested that Bragg send Longstreet with his two divisions

into East Tennessee to clear out Ambrose Burnside, who had occupied

Knoxville in September. That done, Longstreet would be well situated to

return to Virginia, where Robert E. Lee was reminding Davis of his

urgent need for Longstreet and his 15,000 troops. Davis's suggestion

that Bragg detach Longstreet reflected both his lack of appreciation of

the gravity of the Union buildup at Chattanooga and the degree to which

he was swayed by Robert E. Lee. Bragg was in a position to know better,

but he was beyond the force of logical persuasion. On November 3, he

called his corps commanders to a council of war. Longstreet had heard

rumors that he was to be sent away, but he was unprepared for the

finality of Bragg's decision. Bragg told him to move out immediately "to

drive Burnside out of East Tennessee first, or better, to capture or

destroy him" and to repair the railroad. Along the way, he would be

joined by most of the army's cavalry. Bragg would order the divisions of

Carter Stevenson and Benjamin Franklin Cheatham, which had been sent

into East Tennessee on Burnside's flank, to return to Chattanooga at

once, making a net loss to the army of about 4,000 infantry and nearly

all of its remaining cavalry.

|

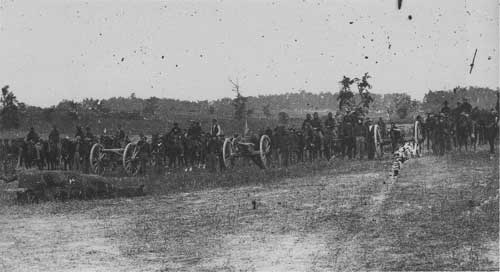

BURNSIDE'S MEN STRUGGLE TO HAUL ARTILLERY UP A MOUNTAIN ROAD IN EASTERN

TENNESSEE. (HARPER'S PICTORIAL HISTORY OF THE GREAT REBELLION)

|

Few were sorry to see Longstreet go. All but Bragg, however, seemed

troubled by any diminution of the army before the Federal buildup at

Chattanooga and by the wild reshuffling of forces along the line that

Longstreet's departure would necessitate. Bragg's determination to hold

the Chattanooga front at all, now that Lookout Valley had been lost,

struck most as foolhardy.

They were right. Bragg had committed the most egregious error of his

checkered career. Without a coherent plan, he divided his army in the

face of a now numerically superior foe who was about to receive even

more reinforcements.

Grant passed the days following Wauhatchie more productively than did

his harrowed opponent. "Having got the Army of the Cumberland in a

comfortable position, I now began to look after the remainder of my new

command." Unremitting pressure from Washington "to do something for

Burnside's relief" and his own lack of confidence in Burnside led him to

turn his attention to East Tennessee. Although many of his problems

were creations of his own mind, Burnside did face considerable

obstacles, as Grant readily conceded.

Grant was at a loss how to respond. Thomas's soldiers were too fagged

from prolonged hunger to endure a sustained offensive. And, recalled

Grant, "We had not at Chattanooga animals to pull a single piece of

artillery, much less a supply train. Reinforcements could not help

Burnside, because he had neither supplies nor ammunition sufficient for

them; hardly, indeed, bread and meat for the men he had. There was no

relief possible for him except by expelling the enemy from Missionary

Ridge and about Chattanooga." And this he was in no position to do.

"Nothing was left to be done but to answer Washington dispatches as best

I could; urge Sherman forward . . . and encourage Burnside to hold

on."

|

A PHOTOGRAPH OF GRANT CIRCA 1863. (CHICAGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY)

|

In truth, Sherman needed little urging during his march across

northern Mississippi and Alabama. He moved with commendable swiftness

until the head of his column reached Fayetteville, Tennessee, on

November 8. There, his command ran up against an extension of the

Cumberland Mountains. It was seventy miles between the Army of the

Tennessee and Stevenson, Alabama, as the crow flies—nearly one

hundred should Sherman choose to follow the line of the railroad, which

began at Fayetteville, turned east to Winchester, and then ran south to

Stevenson.

Sherman elected to follow the latter route. Even so, his army

confronted obstacles similar to those that had wrecked countless wagon

trains of the Army of the Cumberland along Walden's Ridge. Five days

were lost covering the sixty miles between Fayetteville and Winchester.

Beyond Winchester the route was a series of precipitous ascents and

dizzying declines. Then, on November 14, the rains returned—hard

and cold.

As steadily as the rain came telegrams from Washington, exhorting

Grant to action. Grant shared his concern with his friend Sherman: "The

enemy have moved a great part of their force from this point toward

Burnside. I am anxious to see your old corps here at the earliest

moment." On November 13, after Sherman's command arrived at Bridgeport,

Grant urged him to hurry ahead to Chattanooga by himself. Sherman

boarded a steamboat bound for Kelley's Ferry that night.

Grant had plenty of time on his hands during the two weeks between

the Wauhatchie fight and Sherman's arrival at Bridgeport. He turned over

to Smith and Thomas responsibility for developing the details of the

plan that would place Sherman's army in a position to attack Bragg's

right flank on the north end of Missionary Ridge. But he made it clear

that no plan would be adopted until Sherman approved it.

Skeptical of the scheme, Thomas conceded the initiative to Smith, who

seized it with his usual vigor. Beginning on November 8, he made daily

rides north of Chattanooga, reconnoitering the ground from Brown's Ferry

to the knoll opposite the mouth of South Chickamauga Creek.

Smith's analysis of the terrain revealed two critical facts. First,

although the enemy on Lookout Mountain would have a clear view of

Sherman's army when it crossed the bridge at Brown's Ferry, the column

would disappear from sight after it passed Moccasin Point and entered

the foothills along the north bank of the river opposite Chattanooga. As

Grant put it, the Rebels "would be at a loss to know whether they were

moving to Knoxville or held on the north side of the river for future

operations at Chattanooga." Second, Smith's study showed that the

northern end of Missionary Ridge was lightly defended. Only a handful of

cavalry pickets patrolled the Confederate side of the river from the

mouth of South Chickamauga Creek to the right flank of Bragg's army.

By the morning of November 14, the general plan of battle had taken

shape. Subject to Sherman's blessing, it stood as follows: Roads were to

be improved among the foothills north of Chattanooga to allow Sherman's

troops to march rapidly to their crossing sites opposite South

Chickamauga Creek. Smith, meanwhile, would assemble every available

pontoon to ferry the soldiers across the Tennessee River. Once over,

Sherman was to launch the main attack against Bragg's right flank,

pushing on along the railroad toward Cleveland to cut the Rebel line of

communications. Simultaneously, Thomas would advance directly against

Missionary Ridge to pin down the bulk of the Confederate forces.

Reliable intelligence suggested Bragg expected that any attack would

come against his left flank. To encourage this misconception, when

Sherman reached Whiteside's he was to divert his lead division in the

direction of Trenton; with the rest of his command he would continue on

toward Chattanooga over concealed roads. On the day of the

attack—perhaps in deference to Thomas's desires—Hooker was to

assault Lookout Mountain and, if possible, carry it and drive on to

Rossville, to be poised to cut off a Confederate retreat southward.

Sherman reached Chattanooga on the evening of the fourteenth. The

next morning he, Grant, Thomas, and Smith rode out to the hill opposite

South Chickamauga Creek from which Smith earlier had "spied out the

land." Leaving Grant and Thomas at the base of the hill, Smith and

Sherman climbed to the top:

Smith pointed out the portion of Missionary Ridge that Sherman was to

seize. Could the Ohioan carry it before Bragg was able to concentrate a

force to resist him? Smith wondered. Sherman swept the country with his

field glass. Yes, he said, he could take the ridge; what's more, he

could seize it by 9:00 A.M. on the appointed day.

Sherman's successful crossing of the Tennessee River north of

Chattanooga depended on secrecy and exacting preparations. For the

latter, Grant and Sherman looked to Baldy Smith.

|

The party returned to headquarters. Perhaps swayed by Sherman, who of

course wanted every unit he could muster to carry out his mission, Grant

withdrew his support for Thomas's plan to take Lookout Mountain.

Sherman's successful crossing of the Tennessee River north of

Chattanooga depended on secrecy and exacting preparations. For the

latter, Grant and Sherman looked to Baldy Smith. Once again, he was up

to the task. The Vermonter laid out for Sherman his concept of the

operation. Sherman's command was to go into camp among the foothills

north of Chattanooga, hidden from view. One brigade was to encamp beside

the mouth off North Chickamauga Creek. There Smith would assemble his

pontoons and float this brigade downriver to secure a landing just below

the mouth of South Chickamauga Creek. There engineers would throw across

a bridge over which the rest of Sherman's force would cross.

|

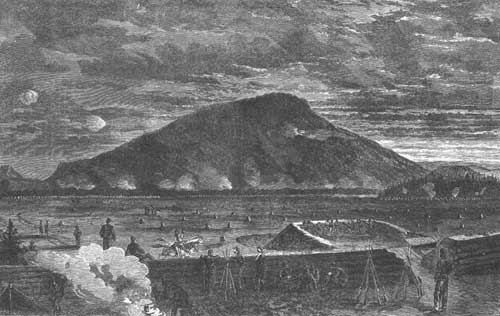

LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN FROM THE FEDERAL WORKS ON CHATTANOOGA CREEK. (LC)

|

Sherman's immediate objective was to turn Bragg's flank, which meant

seizing that portion of Missionary Ridge between Tunnel Hill and South

Chickamauga Creek. If successful, Sherman would gain control of the two

railroads leading east out of Chattanooga. Loss of the rail lines, over

which supplies flowed to the Confederate army, would compel Bragg

"either to weaken his lines elsewhere or lose his connection with his

base at Chickamauga Station," said Grant. At best, it would force him to

withdraw altogether.

Longstreet's departure did little to improve either Bragg's mood or

his clarity of thought. Bragg had decided to hold onto his line around

Chattanooga, the strength or tactical value of which, now that Federal

supplies and troops were flowing into the city unimpeded, was illusory.

To do so, Bragg had slightly under 40,000 infantry and only 500 cavalry,

which ruled out rapid reconnaissance beyond his flanks.

Having given up Lookout Valley as lost, Bragg opted to defend the

mountain itself. On November 9, General Hardee examined the mountain

with Brigadier General John Jackson, temporarily in command of

Cheatham's division while the Tennessean was on leave. It had fallen to

Jackson to defend Lookout Mountain. Their reconnaissance gave Hardee and

Jackson little comfort. "It was agreed on all hands that the position

was one extremely difficult to defense against a strong force of the

enemy advancing under cover of a heavy fire," said Jackson.

On November 12, Bragg placed Carter Stevenson in command of the overall

defense of Lookout and transferred his division to the summit of the

mountain. Jackson was to hold the bench with his own brigade and those

of Edward Walthall and John C. Moore.

|

THE TENNESSEE RIVER ACTED AS A RIVER HIGHWAY FOR FEDERAL SUPPLIES AND

MATERIALS. THIS 1864 PHOTOGRAPH SHOWS SOLDIERS AND CITIZENS WATCHING A

STEAMER GO UPRIVER. (NA)

|

|

A POST-BATTLE PHOTOGRAPH OF UNION ARMY TRANSPORTS ON THE TENNESSEE RIVER

BELOW CHATTANOOGA. (LC)

|

|