|

|

"A VICTORIOUS LITTLE BATTERY"

The northern end of Lookout Mountain loomed over the best

transportation routes into Chattanooga. Its bluffs overshadowed the

channel of the Tennessee River. At the mountain's base, just above the

river, ran the trackage of the Nashville & Chattanooga

Railroad. Above the bluffs, on a natural but improved rock shelf, was

the main road, the Wauhatchie Pike. Higher still were other less used

routes, including the old Federal Road.

Despite the importance of these avenues and Lookout's commanding

position over them, Rosecrans was forced to abandon the mountain to the

Confederates when he withdrew into Chattanooga following the Battle of

Chickamauga. His army could not maintain a line that encompassed both

the city and the mountain.

|

AN EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY VIEW OF MOCCASIN POINT FROM LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN.

(NPS)

|

Geography, however, gave the Federals an opportunity to provide

added security to their lines around the city and, most important, made

it difficult for the Confederates to possess the mountain. Moccasin

Point, the great land form created by the hairpin bend of the Tennessee

as it flowed westward from Chattanooga, was the key. Moccasin Point

offered excellent positions for artillery; the guns the Federals placed

on the hills at the southern end of Stringers Ridge were like a dager

thrust forward to keep the Confederates at arm's length. Dug into an

extensive series of earthen and log fortifications, the guns of the 10th

Indiana Battery and the 18th Ohio Light Artillery commanded much ground

from their fortified hilltops. Should the Confederates attempt to

attack the Federal lines around Chattanooga from the south, the guns

could fire into the flank of the force as it moved to the assault.

Should they attempt to cross the Tennessee from near the base of Lookout

Mountain to strike Rosecrans's remaining supply link, the guns commanded

the best crossings. Most important, the Indianans' and Ohioans' guns on

Moccasin Point denied the Confederates easy movement across the tip of

Lookout Mountain. The routes of the several roads and almost the

entirety of the northern tip of the mountain were within range of the

Moccasin Point batteries. They challenged and prevented the movement of

men and supplies in any but small numbers over the tip of the mountain

in daylight. Even single wagons were potential targets. Sam Divine, a

young civilian in Chattanooga during the siege, remembered:

"On one occasion I witnessed a very daring feat made by a teamster

driving a four-mule team drawing a wagon . . . . The gunners discovered

him as soon as he reached the level of the plateau and fired . . . . I

saw every shell when it burst and watched the progress of the race till

it was ended . . . . The most critical time was when he reached the open

spaces directly in front of the battery, where the road was extremely

narrow and there was a precipice of several hundred feet perpendicular

down to the railroad track below . . . . When he appeared at the opening

he had the throttle wide open and those rebel mules were racing against

cannonball time. Boom! Boom! Boom! went six rifled guns; pow! pow! pow!

echoed the bursting shells against old Lookout's ribs, but Johnny Reb

had beat'em to it and was happy on his way down the other side."

Confederate activities around Robert Cravens's white house on the

mountain's slope brought it under fire. Colonel John Bratton of the 6th

South Carolina writing from there on November 3, 1863, said:

"My Qrs. are in the Craven House . . . . The enemy gave it a shelling

the other day while we were passing this point to support Gen. Law who

was having a brush with the enemy and again since. There are two or

three holes through the room where I am sitting. The Mocasin Battery

which you have seen in the papers, does this work."

|

EARTHWORKS ON MOCCASIN BEND. (NPS)

|

For the Confederates, this Federal fire meant they could supply and

maintain only a single brigade in Lookout Valley west of the mountain,

a force too small to hold the area. When the Federals seized Brown's

Ferry and Lookout Valley on October 27 and 28, 1863, they did so without

a serious challange from the Southerners. The Moccasin Point batteries

prevented practical and timely Confederate reinforcements. A month

later, during the Battle of Lookout Mountain, the batteries supported

Joseph Hooker's assault by firing into the Confederate positions from

the rear and flank as the Federals swept the Southerners around the

northern tip of the mountain.

The Moccasin Point batteries had helped hold the Confederates at bay

and then throw them back from the Gateway to the Deep South.

|

Commanders elsewhere along Bragg's tenuous front also questioned the

defensibility of their positions. Breckinridge, in command of the center

and right, was left to defend a position five miles long with just over

16,000 troops. After a bit of shuffling about, Stewart's division

finally settled into position in the soggy fields of Chattanooga Valley,

from the east bank of Chattanooga Creek to the base of Missionary Ridge.

William B. Bate's division and that of Patton Anderson were arrayed

behind breastworks of logs and earth along the western base of the

ridge. Cleburne's division held the right just south of Tunnel Hill.

Pickets from each command were shaken out a mile closer to the Federal

entrenchments. A few batteries were left up on the ridge, but no one

thought to dig them in.

Patton Anderson was appalled at the sorry state of his sector. "This

line of defense, following its sinuosities, was over two miles in

length—nearly twice as long as the number of bayonets in the

division could adequately defend." Watching the ever-growing number of

Federal campfires, many Confederate troops did more than just

ruminate—they gave up the game as lost and walked across the valley

under cover of darkness to surrender.

Nature favored the Confederates at this juncture, but part of the

blame for the delay during the final leg of the march rested on

Sherman's shoulders.

|

The slow going of Sherman's command gave wavering Rebels ample time

to contemplate desertion. The Ohioan had started promptly enough. He

lost no time in pushing Ewing's division toward Trenton to make the

agreed-upon demonstration against the Confederate left rear in Lookout

Valley. To Sherman's chagrin, the march of the main column did not

proceed apace. Struggling along through cold rains and bitter winds over

icy wagon roads, his other three divisions made miserable time between

Winchester and Bridgeport.

Nature favored the Confederates at this juncture, but part of the

blame for the delay during the final leg of the march rested on

Sherman's shoulders. Three weeks earlier, Thomas wisely had suggested

to Hooker that he leave his wagons while he marched from Bridgeport to

Chattanooga; he had had the good sense to act on Thomas's

recommendation. But Sherman decided to march with his trains. It was a

terrible miscalculation. Wagons sank in the mire, slowing the march to a

crawl.

|

VIEW OF LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN FROM CHATTANOOGA IN 1864. (LC)

|

|

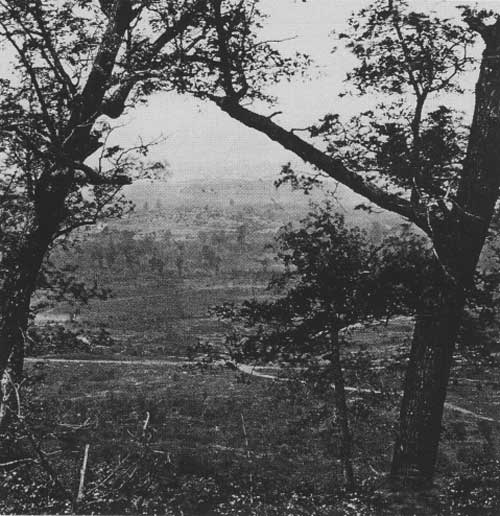

ORCHARD KNOB RISES IN THE DISTANCE BETWEEN THESE TWO TREES. (USAMHI)

|

Grant was beside himself. Burnside had fallen back onto his defenses

at Knoxville with Longstreet in close pursuit. Although Burnside was

confident he could resist a few days longer, the War Department was

frantic for Grant to act. That, of course, he could not do without

Sherman. Grant had hoped to begin offensive operations on November 21.

By the evening of the twentieth, however, only one brigade of Sherman's

command had crossed the pontoon bridge at Brown's Ferry. Grant

rescheduled the attack for November 22. Again Sherman was unready. All

of John Smith's division had crossed the Tennessee River and gone into

camp north of Chattanooga, but Morgan Smith was only partially over,

and Ewing had barely reached Hooker's line north of Wauhatchie.

When Grant postponed the attack again—this time until November

23—Thomas renewed his pleas that Hooker be allowed to keep

Howard's corps and attack Lookout Mountain. Thomas was worried that

Sherman's three days of floundering about in Lookout Valley might have

tipped Grant's hand and that Bragg would strengthen his right flank.

Grant rejected Thomas's plan—Sherman would make the main attack

against the Rebel right, regardless of when he came up. Bragg had done

nothing to strengthen his right; Ewing's display in the upper Lookout

Valley had deceived him into thinking that Sherman would attack his

left. Even after Sherman's main body and Howard's corps crossed Brown's

Ferry, Bragg misjudged the Federal objective. He assumed correctly that

Grant was trying to drive a wedge between his army and Longstreet's

corps, but he guessed wrong as to where it would be driven. Bragg

concluded that Grant was sending Sherman against Longstreet, rather than

to strike his own right flank. On this assumption, Bragg weakened his

lines even more. On November 22, he ordered Cleburne to withdraw his own

and Buckner's divisions from the line and march them to Chickamauga

Station, where they would board cars to join Longstreet.

Bragg had opted to slice away 11,000 more men from his small army at

precisely the moment Sherman was reinforcing Grant with nearly twice

that number.

Colonel Aquila Wiley of Hazen's brigade saw a surprising sight at

sunset on November 22. "Three columns are visible moving up Missionary

Ridge on three different roads. I should think the columns consist of at

least a brigade of 1,000 men each," Wiley reported to Hazen. General

Wood had also been watching the "singular and mysterious" movement

across the valley.

Wood and Wiley had witnessed the withdrawal of Cleburne's division.

They reported the sighting through the chain of command to Grant's

headquarters, along with the claims of two deserters that the

Confederate army was falling back.

Grant took Wood's message seriously. Deserters on Phil Sheridan's

front had said the same thing. If the Rebel army was withdrawing, Grant

reasoned, it was imperative that he disrupt Bragg's movement to prevent

him from reinforcing Longstreet. Before dawn, he instructed Thomas to

drive the enemy pickets from his front in order to force the

Confederates to reveal the strength of their main line. Since the best

evidence of the enemy's departure had come from Wood's sector, Thomas

charged him with conducting the reconnaissance. The orders were

unambiguous: Wood was to avoid a collision with the enemy and return to

his fortifications after completing the reconnaissance.

|

|