|

|

WALKER, THE SOLDIER ARTIST

The striking terrain of the Chattanooga region added a scenic

dimension to the fighting for the Gateway to the Deep South. Lofty

mountains and ridges loomed over the armies, and the heights offered

spectacular views. The November 1863 battles for Chattanooga seemingly

took place in a vast, outdoor arena.

The picturesque potential of the battles on Lookout Mountain and

Missionary Ridge was not lost on one of the mid-nineteenth century's

foremost members of the artistic community—Englishman James

Walker. Born in 1818, Walker came to America with his family in 1824.

At age nineteen, he moved to Mexico and for a time taught art at the

Military College of Tampico. He was living in Mexico City when the

Mexican War began and accompanied the American army as an interpreter in

the Mexico City campaign. His experiences in Mexico led him to produce a

series of paintings chronicling that conflict and brought him national

recognition in the United States as a military artist. Acknowledging his

talents, Walker received a commission to paint a nine-by-nineteen-foot

image of The Battle of Chaputtepec for the United States Capitol.

By the time that work was completed in 1862, the American states were at

war with themselves and Walker had another conflict to record on canvas.

Thereafter, he produced thirty works on the War Between the States

encompassing images of camp life, individuals, and several battles,

including Gettysburg. It was his work with the Battle of Lookout

Mountain or "the Battle Above the Clouds," that gave him lasting

recognition.

|

A JAMES WALKER PAINTING OF UNION OFFICERS DESCENDING LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN

AFTER THE BATTLE. (COURTESY OF THE WEST POINT MUSEUM, US MILITARY

ACADEMY)

|

Walker spent time with the Army of the Cumberland in Chattanooga in

early 1864 and was moved to produce a series of works depicting the

military action in the area. With an eye for detail and accuracy, Walker

carefully studied the battlefields. He walked and rode over the scene

of the engagements, made sketches, and interviewed important Union

participants, such as George H. Thomas, Joseph Hooker, Dan Butterfield,

and John White Geary. He even employed a photographer to produce images

for later reference. "I am confident that I can give our people here to

the North a better idea of what has been accomplished down there than

any report that can be written. No one can describe Lookout in word

painting so as to make it satisfactorily understood," wrote the artist

at the conclusion of his Chattanooga visit. From these sources, Walker

first produced The Battle of Chickamauga and The Battle of

Lookout Mountain (see back cover), both commissioned by the United

States government. Later, he also produced Mounted Union Officers on

Lookout Mountain, Union Cavalry on Lookout Mountain, and another

version depicting the battle itself.

Walker's second image of the Battle of Lookout Mountain was his

largest work and is considered by many to be his masterpiece.

Commissioned by "Fighting Joe" Hooker to commemorate that general's

part in "The Battle Above the Clouds," this second Battle of Lookout

Mountain (see below) covers a thirteen-by-thirty-foot canvas and was

produced for $20,000 over a four-year period. Upon completion in 1874,

the painting toured the country with stops in New York, Philadelphia,

and San Francisco. Hooker said of Walker's grandest work, "I wanted it

to be the representation of an American battle as it was. . . . You

appear to have adhered to the instructions with singular fidelity and

success. It is unnecessary for me to speak of the landscape, except in

terms of the highest approval. . . . I am equally gratified with the

representation of the dramatis personae on your canvas. While later

generations of art and military historians would acknowledge greater

artistic license than did Hooker, The Battle of Lookout Mountain

is one of the most visually significant documents on that important

engagement.

|

JAMES WALKER'S SECOND VERSION OF THE BATTLE OF LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN.

(NPS)

|

Following the completion of The Battle of Lookout Mountain,

Walker turned his artistic attention to a new American arena, the West.

Moving to California in 1876, Walker produced more than thirty images of

Western life and California scenes before dying in 1889 at age 70.

|

Back at the Gillespie house, Stevenson and Jackson waited patiently

for Cheatham to return. It was well after midnight when a courier from

Bragg galloped up and announced that all troops west of Chattanooga

Creek were to start at once for the far right of the army. No one could

find Cheatham so Stevenson took responsibility for the move. Up on the

frigid slope of Lookout Mountain, the firing died out a little after

midnight.

Hooker's success on Lookout Mountain was of little interest to Grant.

In his view, Sherman's march against Bragg's right was the real battle,

and on it he pinned his hopes. As darkness fell on November 24, Grant

believed his faith in his friend vindicated. Sherman assumed he had

carried Tunnel Hill, and Grant based his planning on the impression that

Sherman need only press his advantage at daybreak to roll up Bragg's

flank and complete his victory.

Grant's instructions to Sherman were simple: he was "to attack the

enemy at the point most advantageous from your position at early dawn."

To Thomas went a supporting role: "I have instructed Sherman to advance

as soon as it is light in the morning, and your attack, which will be

simultaneous, will be in co-operation. Your command will either carry

the rifle-pits and ridge directly in front of them or move to the left,

as the presence of the enemy may require."

|

HOOKER SITS ATOP THE CONQUERED POINT LOOKOUT. (USAMHI)

|

|

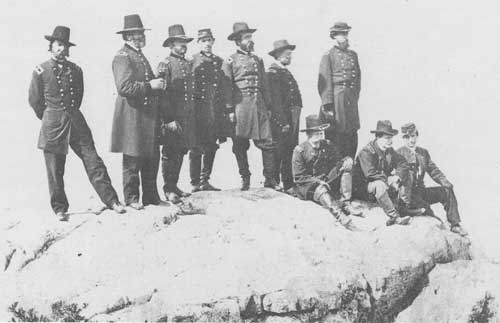

GENERAL THOMAS (SECOND FROM LEFT) AND HIS STAFF ON POINT LOOKOUT IN

1863. (LC)

|

Grant envisioned no serious role for Hooker; at best his was to

divert Bragg's attention from his right flank by a further display on

Lookout Mountain.

But Thomas flouted Grant's directive. He called Hooker down to the

valley, where he could make a more tangible contribution by

demonstrating directly against Bragg's left flank on Missionary Ridge.

Also, Thomas wanted to ensure that his own right was protected.

By 10:00 A.M., when Hooker got started, Thomas was feeling much

relieved. A stunning revelation had compelled Grant both to endorse

Thomas's orders to Hooker and to postpone Thomas's own advance toward

Missionary Ridge. When the morning fog burned off, Grant and his staff

realized that Sherman did not hold Tunnel Hill, which bristled with

Confederate cannon and toward which long lines of Rebel infantry were

marching. Grant, Thomas, and their staffs waited on Orchard Knob with

ill-concealed impatience for Sherman to go into action.

But Sherman was in the throes of indecision. Dawn found him no more

capable of grasping the reality of the Confederate presence on Tunnel

Hill—or of overcoming it—than he had been at sunset the day

before. Neither did he appreciate the overwhelming superiority he

enjoyed: facing Sherman's four divisions (16,000 men) was Cleburne's

three small brigades, numbering 4,000. And only Smith's Texas brigade

actually stood atop Tunnel Hill.

Yet Sherman hesitated. Not until 8:00 A.M., ninety minutes after

Sherman should have launched his attack, did his weary men finally

receive orders to quit fortifying their fronts. He finally decided to

strike Tunnel Hill simultaneously from the north and northwest with just

two brigades: those of John Corse and John Loomis of Ewing's division.

Corse would come at Tunnel Hill from the northwest. Loomis, on his

right, was to approach Tunnel Hill through the open fields between the

railroads. To John Smith and Morgan Smith went ill-defined supporting

roles; to Jefferson C. Davis went no role at all.

|

A DECEMBER 1863 VIEW OF A RAILROAD BRIDGE OVER CHATTANOOGA CREEK. (LC)

|

The results of Sherman's poorly planned assault were predictable.

Corse ran up against Tunnel Hill with only 920 men and was decimated in

two successive charges. Before making a third, Corse wanted to know if

Sherman wanted him to try again. "Go back and make that charge

immediately; time is everything," Sherman snarled.

Sherman's dawdling was Cleburne's salvation. Every minute the Ohioan

delayed brought the Irish immigrant vital reinforcements. The first came

just after sunrise, when Brigadier General John Brown's Tennesseans

staggered into position. With infantry on hand to support them, the

batteries of Calvert and Goldthwaite were wheeled into place above the

tunnel. Cummings brigade showed up next and was fed into line to the

left of Brown. Lewis's Orphan Brigade reported to Cleburne next.

Cleburne left him behind Smith, on the eastern slope of Tunnel Hill, as

a reserve.

At 10:30 A.M., Sherman's cannon unleashed a barrage on Smith's

Texans. Behind the exploding shells came Corse's infantry. Lieutenant H.

Shannon, in command of Swett's battery atop Tunnel Hill, wheeled his

guns to face the bluecoats. He shredded their ranks with canister, but

the Yankees kept coming. They charged to within fifty feet of Smith's

line before breaking. Smith was dangerously wounded, and brigade command

passed to Colonel Hiram Granbury.

|

MAJOR GENERAL PATRICK R. CLEBURNE (USAMHI)

|

|

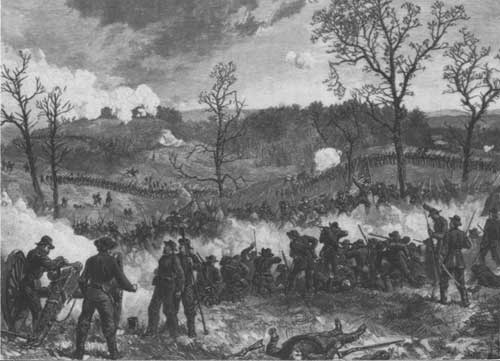

ALFRED R. WAUD'S POSTWAR DRAWING OF CLEBURNE'S REPULSE OF SHERMAN AT

MISSIONARY RIDGE. (NPS)

|

Corse had attacked with only a part of his brigade. Before trying

again, he called up the remainder and sent to Sherman for help.

But Corse had no intention of waiting for reinforcements before

attacking a second time. Placing himself in the front line, at 11:30

A.M. Corse ordered an advance. This time the Yankees came within a few

feet of the enemy works before giving way. Corse fell, slightly wounded.

While he was carried to the rear, his troops kept up the pressure on the

Texans, holding onto the northern slope of Tunnel Hill with a rabid

tenacity.

Cleburne worked feverishly to dislodge the Federals. He positioned

Douglas's battery near Granbury's right flank to enfilade the Yankee

left, then called forward two of Lewis's regiments to extend his line

eastward.

When the Federals at last gave way, the Texans surged over their

breastworks and into the ravine after them. Regrouping on the rise north

of Tunnel Hill, the Yankees beat back the counterattack. Colonel

Charles Walcutt, assuming command from Corse, appealed to Sherman for

orders.

Sherman had had enough. Corse's setback convinced him that the

northern approach to Tunnel Hill was bankrupt so he refused to send

Walcutt reinforcements, telling him simply to hold his ground. For all

practical purposes, the first Federal effort to take Tunnel Hill was

over at noon.

How was it that Cleburne had been free to turn his undivided

attention to pulverizing Corse's brigade? Largely because Loomis had

taken literally General Ewing's admonition that he "under no

circumstances" bring on a general engagement, marching his brigade only

as far as the edge of the woods. Nearly half a mile of meadows and soggy

fields lay between Loomis and the railroad tunnel, on top of which

Cleburne's artillery stood, ground Loomis was averse to cross.

At 10:30 A.M., Loomis was handed unexpected orders. Corse was about

to assault Tunnel Hill, and Loomis was to advance at once in

cooperation. Loomis made a good faith effort at complying, but he had no

idea where Corse's flank lay or when or in what direction Corse might

attack. So Loomis moved out blindly. Guiding on the mouth of the tunnel,

he opened a gap of 400 yards between his left and Corse's right.

Loomis never had a chance. The instant his men stepped into the

clear, they were easy marks for the two batteries atop the tunnel. The

Yankees made it as far as the railroad embankment at a point where it

curved south.

Loomis was in trouble. His three regiments behind the embankment were

leaking wounded rearward at an alarming rate, and his left-flank

regiment, the Ninetieth Illinois, had the impossible duty of trying to

make the connection with Corse. The brigade had strayed too far south,

and the Ninetieth had lost so many men that it covered a front barely

the width of two normal-sized companies. Worse yet, Cleburne had pushed

two regiments off Tunnel Hill and onto the flat near the Glass farm,

opposite the left flank of the Ninetieth Illinois.

After thirty minutes in this untenable position, Loomis summoned two

regiments to roust the Confederates from the farm. Lieutenant Colonel

Joseph Taft of the Seventy-third Pennsylvania led his own regiment and

the Twenty-seventh Pennsylvania across the flat on the run, sweeping the

Rebels from the Glass farm. Taft ordered a halt at the foot of Tunnel

Hill, but his order was misunderstood, and the Twenty-seventh

Pennsylvania continued upward to within thirty yards of the hilltop.

Back on the flat, Loomis imagined that the Confederates were

preparing to sally forth of Tunnel Hill into the gap that Taft had

failed to close. Desperate to forestall an attack, Loomis again pleaded

for reinforcements. Again only a single brigade was sent to bolster the

flagging Federal attack. This time the duty fell to Brigadier General

Charles Matthies. Confederate artillery pulverized his brigade as it

crossed the flat, and the survivors took cover along a sunken wagon

road.

As his brigade sorted itself out, Matthies realized that he had

veered too far to the left to cover Loomis's flank. In an effort to

close the gap, he ordered the Tenth Iowa from the foot of Tunnel Hill

over to the far right. Colonel Holden Putnam, the commander of the

Ninety-third Illinois, led his regiment up the hill at full tilt.

Putnam was shot dead and his Illinoisans were stopped thirty yards from

the crest. Regrettably, General Matthies chose to reinforce what clearly

was a losing proposition, sending all but the Fifth Iowa up to bolster

the Ninety-third Illinois. Matthies went up himself a few minutes later,

only to be struck by a bullet in the head. In the distance was another

double line of blue sweeping across the flat, alone and unsupported. It

was the brigade of Brigadier General Green Raum, whom Sherman committed

to the stalled attack against Tunnel Hill at 2:00 P.M. By the time Raum

reached Tunnel Hill, the situation along Matthies's front had

deteriorated beyond repair. In hopes of reversing the tide, Raum sent

two of his regiments up the hill.

Cleburne was in trouble. With Raum's two fresh regiments about to hit

his front, Corse's Federals plunking away at his right flank, and the

ammunition of his men down to only a handful of cartridges, it looked

for the first time that afternoon as if Cleburne's salient might be

broken.

|

THE EAST TENNESSEE AND GEORGIA RAILROAD PASSES THROUGH MISSIONARY RIDGE

AT TUNNEL HILL. (LC)

|

But fortune favored the Irishman. General Hardee had plied Cleburne

with reinforcements. With the advantage of interior lines and easy

ground to traverse, the Rebels could marshal troops on and near Tunnel

Hill far faster than Sherman's disorganized generals could bring units

to bear against it. Cleburne fed fresh troops into the line just as

Raum's two regiments charged past Matthies's stalled brigade. After Raum

was halted, Cleburne ordered a counterattack all along the line.

The effect was electric. The Rebels bounded down the slope at 4:00

P.M. So spontaneous did the effort seem that some participants swore no

order was ever given to charge.

After three nerve-wracking hours, the Federals had neither the

strength nor the ammunition to resist. Yankees surrendered by the

score, and the survivors slipped across the flat to safety. General John

Smith was on hand to greet them, "smoking a pipe as calmly as he would

in camp," reflected a begrimed survivor. "Well, boys, that's a tough

place up there," he laughed. His joke fell flat, and the men drifted

past in sullen silence.

So ended one of the sorriest episodes in this or any other battle of

the war. In his assault on Tunnel Hill, Sherman exhibited an egregious

lack of imagination. He attacked Cleburne's salient head-on and with

only a fraction of his force, rather than look for a way to outflank

Tunnel Hill.

|

|