|

Fort Raleigh National Historic Site North Carolina |

|

NPS photo | |

After the changes wrought by four centuries, it is not easy to imagine the America seen by the small band of settlers who gained for England a foothold in the New World. They had left behind the comfortable limits and familiar rhythms of European civilization for a boundless and unpredictable world in which vigilance, courage, and endurance were needed just to survive.

Their colony on Roanoke Island played a part in a broader historical event: the expansion of the known world. In the century after Columbus voyage had put a new continent on the map, Europe's seagoing nations rushed to participate in the discoveries, to claim part of the prize. England was something of a latecomer to the race for the New World. By the time the English began to send out voyages of exploration, Spain was already entrenched in what is now Florida and Mexico. English privateers had been sailing to the North American coast since 1562, slave-trading and preying on Spanish shipping loaded with royal loot from Mexico. No one, though, had seriously considered a colony in North America until 1578, when Sir Humphrey Gilbert, armed with a charter from Queen Elizabeth "to inhabit and possess . . . all remote and heathen lands not in actual possession of any Christian prince," made the first of two attempts to reach Newfoundland. After he died on the second voyage, Sir Walter Raleigh, his half-brother, decided to carry on the venture, and obtained a similar charter from the queen. Reports from his expedition in 1584 sang the praises of the rich land, and by the middle of the following year England had made its first tentative move to transplant English culture to foreign soil. The new colony was called Virginia, after the Virgin Queen.

England's motives for settling the New World ranged from the mercenary to the idealistic. One of the primary spurs, at least for Raleigh, was the prospect of an ideal base for forays against French and Spanish shipping. Publicist Richard Hakluyt conjured up visions of gold and copper mines and cash crops, which fit neatly with Gilbert's plan to put "needy people" to work there. The anticipated Northwest Passage was another strong lure. Finally, like Spain's efforts to make the New World Catholic, England wanted to spread the new Protestant religion among the "savages"—to claim the land for God and Queen, although not necessarily in that order. In a sense the two settlements at Fort Raleigh represented England's schooling in establishing a colony. The first was more like the Spanish operation—militaristic, dependent on the home country, and exploitative of the native Americans. The second was intended to be a permanent colony, with women and children, fewer soldiers, and a sounder agricultural base. Although all of the settlers who were to have built The Cittie of Ralegh disappeared, their dream of an English home in the New World was realized 20 years later at Jamestown.

England's Flowering

The reign of Queen Elizabeth (1558-1603) was one of the high-water marks of English history. After the troubled years under her sister Mary I—known as "Bloody Mary for her religious persecutions—the English welcomed the spirited, intelligent, and strong-willed Elizabeth. England had long been a small, somewhat static nation, coveted by the European powers and castigated by the Pope as a hotbed of Protestantism. Now there was a sense of possibilities, of national purpose, under the young queen.

Elizabeth's radiant dress sparkling court, and adroit advisors set the tone for the period, and her personality helped give the nation a strong self-image: dynamic yet stable, where ventures and reputations rose and fell with dizzying speed while the machinery of government ground on. Hers was a rule of benevolent authoritarianism and her shrewd and sensitive handling of people earned total loyalty from her advisors and early compliance from Parliament. She felt no need for a standing army in the French fashion. The aristocracy's grand homes changed from fortified castles to open manors, reflecting their owners confidence in the stable social order and in the state's ability to defend them. That strength also benefited the common people, who took pride in England's growing international prestige and enjoyed an improved standard of living. Elizabeth's reluctance to indulge in petty wars and her shrewd financial management kept the Crown on a sound financial footing for most of her rule. The old feudal system had faded, and the economy was opening up, with a new middle class of merchants searching for investments and expanded markets for the products of England.

So with new strength and self-confidence, England turned outward, and began to make the sea its own. The nation finally had the means and the will to challenge Spain's and Portugal's dominance of world exploration and exploitation. To that end "privateers" served an important function. Their private fleets were supposed to raid only the shipping of official enemies, but during the cold war with France and Spain, the ships of both countries were fair game.

Successful sea captains weren't the only ones to find Elizabeth's favor. Under her rule, England enjoyed a flowering of the arts, especially literature. Names like Shakespeare, Bacon, Spenser, and Sidney commanded as much respect as Raleigh, Grenville, Drake and Hawkins.

Sir Francis Drake's circumnavigation of the world (1577-80) was also the most famous English privateering voyage. He looted Spanish shipping and, by flouting Spain's claims to monopoly in the Americas, proved the weakness of its empire.

The First Colony

Harsh Lessons

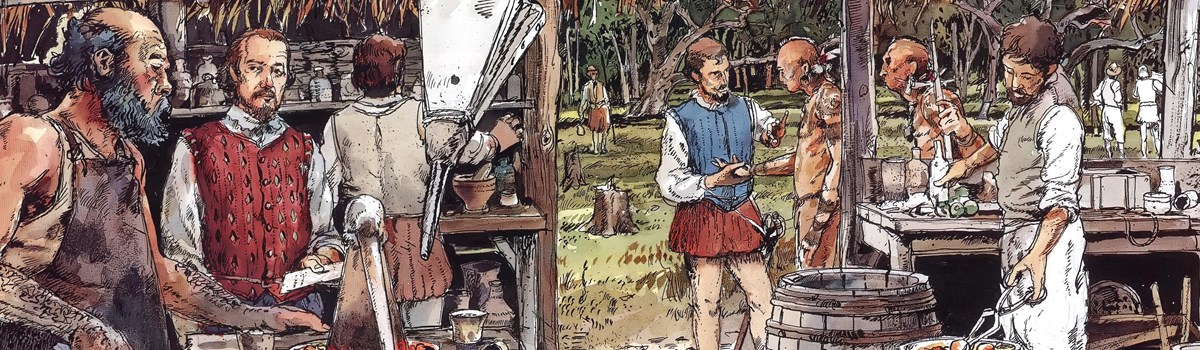

After Captains Amadas and Barlowe returned in 1584 from their expedition to the New World with reports of "a most pleasant and fertile ground," Sir Walter Raleigh had little trouble getting the Queen and a number of other investors to back his colony. In the spring of 1585, 500 men—108 of them colonists—set sail for Virginia in seven ships commanded by Raleigh's cousin, Sir Richard Grenville. After weeks of searching (and privateering), they found, with the help of nearby Indians, a fertile, well-watered, and defensible spot on Roanoke Island. Ralph Lane was named Governor of the colony, and the settlers immediately set to work building a fort for defense against the Spanish.

Although the colonists established a trading relationship with the Indians, they soon realized that, with the coming of winter, providing for themselves would not be easy. Many supplies had been lost when one of the ships ran aground, and since they cultivated little land, the colonists soon grew dependent on the Indians, cadging food and robbing their fish traps. But as winter deepened, the Indians had less food to spare, and in any case were growing tired of trinkets. Disenchantment set in, especially after measles and smallpox brought by the settlers began to kill the Indians.

By 1586 the colonists were anxious to relocate. Lane had concluded that the site wasn't suitable as a privateering base, and tales of Indian gold and a possible northwest passage were circulating. So in late winter Lane took a party up Albemarle Sound. Chief Wingina of the Roanoke Indians saw a chance to rid himself of the demanding colonists. He told inland tribes that Lane planned to attack them, so they deserted their villages, depriving Lane's party of food. But Lane made it back to the colony, and by late spring there were open battles. When a member of a friendly tribe warned Lane that Wingina planned an assault on the island, Lane arranged for a parley with Wingina and other Indian leaders. But at a prearranged signal, the English opened fire. Wingina was killed and beheaded.

A week later Sir Francis Drake's privateering fleet was sighted. His offer of the ship Francis was readily accepted, because Grenville, due by Easter with supplies, had never arrived. Lane knew that "it was unlikely that he would come at all," as his ships would probably be pressed into service against the Spanish. With the Francis, the colonists could return to England after Lane had finished his explorations. But a storm forced the ship, loaded with supplies and several of the colony's most responsible members, to leave the harbor and sail for England. Demoralized, Lane and the colonists decided to leave with Drake.

Two days later a supply ship sent by Raleigh arrived. Grenville himself finally arrived two weeks later, only to find a deserted settlement. After searching the island he left 15 men to guard the settlement until a new group of colonists could be recruited.

"...a most pleasant and fertile ground."

Sir Walter Raleigh (1554-1618) was the imaginative force behind the Roanoke colonies. His rise to favorite of Queen Elizabeth I was dazzling, sustained by his service as explorer, soldier, and seaman, and his gifts as a writer. His position brought him vast estates, influence, and a knighthood, but by 1592 his star had dimmed. In 1618 he was executed after a long stay in the Tower for allegedly plotting to dethrone James I.

Thomas Hariot (1560-1621), lifelong friend and advisor to Raleigh, was a leading intellectual figure of his time. He founded the English school of algebra, constructed telescopes contemporaneously with Galileo, and discovered the laws of refraction independently of Descartes. When chosen as scientist for the 1585 voyage, he had been living at Raleigh's home, teaching mathematics and navigation to his pilots.

Portraying the New World

Raleigh's choice of Thomas Hariot and John White to accompany the 1585 colony was inspired. Through them we glimpse the New World as the English saw it. Hariot was a 25-year-old astronomer, mathematician, and master of navigation when he was chosen as observer and chronicler for the voyage. His job was to explore, catalogue, and collect, but his accomplishments far transcended those duties. He taught himself Algonquian and became the liaison between the colonists and the native Americans. In his widely-read A brief and true report of the new found land of Virginia, Hariot described the native animals, classified food sources and building materials, and assessed the commercial potential of "commodities" there, from silk to iron. He also gave a detailed and perceptive account of the villages, customs, clothing, crafts, agricultural methods, and religion of the Carolina Algonquins. Hariot chastised his fellow colonists for being "too harsh with them and killing a few of their number for offenses which might easily have been forgiven." But he was an enthusiastic supporter of colonization, concluding, "I hope there no longer remains any reason for disliking the Virginia project. The air is temperate and wholesome there, the soil is fertile ... And in a short time the planters may raise the commodities I have described. These will enrich themselves and those who trade with them."

The second edition of Hariot's book was illustrated with engravings based on watercolors by John White. Trained as a surveyor, White was also a skilled illustrator, and no stranger to the New World, having made drawings of Eskimos while on the Frobisher expedition to North America in 1577. His work was a happy complement to Hariot's text, recording with skill and sensitivity the features, styles, and daily pursuits of the native Americans. His pictures ring true; they portray the Indians as neither base savages nor noble innocents, but as members of a culture that, in its harmony and resourceful adaptation to its environment, was worthy of attention and respect. He captures the telling detail: The portrait of the wife of a chief shows her wearing the arm sling indicative of high station. Her 8-year-old daughter wouldn't wear a deerskin apron like her mother's until she reached ten. White so gained the confidence of the villagers that he was able to quietly observe and record not only their ceremonies, but also their routine activities: fishing, canoe-making, farming, and eating. Here they eat boiled maize on a reed mat. Wrote Hariot: "They are verye sober in their eatinge, and consequentlye verye longe lived because they do not oppress nature." White also made beautifully colored scientific renderings of the exotic wildlife. Hariot dwelled on the culinary aspects of this bestiary. On tortoises: "Their heads, feet, and tails look very ugly, like those of a venomous serpent. Nevertheless, they are very good to eat." White's maps of the Roanoke Island area were for over 80 years the base for most European maps of the region.

Raleigh's flagship, the Ark Ralegh, was similar in design to those on which the colonists sailed, though larger. Rechristened the Ark Royal, it led the English Navy against the Spanish Armada.

The Lost Colony

A Silent "Cittie"

By 1586, Raleigh was already planning another colony in Virginia. This one would be more ambitious, with its own coat of arms and the title, "Cittie of Ralegh." It would be agrarian rather than militaristic, less an adventure than a commitment. Raleigh's decision to locate it on the lower end of the Chesapeake Bay was prompted by Lane's report of friendly Indians and a good natural harbor. The inclusion of 17 women and 9 children among the 110 colonists would make this a long-term, self-perpetuating settlement. Instead of wages, each settler was deeded a 500-acre plot, thereby giving him a stake in the undertaking. John White, the artist who had accompanied the first voyage, was appointed Governor, to be aided by 12 assistants.

When the three ships sailed in May of 1587, the plan was to stop briefly at Roanoke Island to resupply Grenville's party. But when they arrived in July, the pilot Fernandez insisted that the summer was too far advanced to go further, and the colonists were left at Roanoke. It wasn't an auspicious beginning. They had already failed to pick up salt and fruit in Haiti, and the Indians' hostility had not cooled since the first group had left. They had attacked the men left by Grenville. White reported: "We found none of them . . . sauing onely we found the bones of one of those fifteene." Through Manteo, who had visited England and was appointed "Lord of Roanoke" by the English, White arranged a peace conference, but a misunderstanding over the date made poor relations worse. Thinking the Indians had rejected their offer, the colonists attacked what they mistakenly thought was a hostile village, killing one Indian. After the incident the two cultures coexisted uneasily.

White's burdens were lightened when his daughter gave birth in August to Virginia Dare, the first English child born in the New World. A week later, however, he was forced to return to England for badly needed supplies. But upon arrival, his ship was pressed into service against the threat of the Spanish Armada. All White could do was petition the Queen through Raleigh and wait. Finally, in 1590, he got passage on a privateering voyage. As the party stepped ashore, there was no sign of the colonists except the letters "CRO" carved on a tree. When they approached the settlement, there was only silence. The houses had been taken down and a palisade constructed, on one post of which was carved "CROATOAN," the name of a nearby island. The colonists had agreed on this kind of message if they had to leave Roanoke, but there was no Maltese cross, the signal that trouble had forced their departure. White's armour lay rusting in the sand, indicating that the colonists had been gone for some time. He wanted to sail to Croatoan, but low provisions, the loss of sea anchors in a storm, and the privateers' impatience prevented them from stopping there. Raleigh made several attempts to locate the colonists between 1590 and 1602, but no trace was found. Their fate will probably never be known. It is likely that they were attacked by Indians, and those not killed were assimilated into the local tribes.

The "Newe Forte in Verginia"

The quiet wooded area at the northern tip of Roanoke Island was the scene 400 years ago of the struggles of some 250 colonists. From this site 116 men, women, and children disappeared forever. On the 355 acres of Fort Raleigh National Historic Site are a reconstruction of the small earthen fort they built, and the sites of part, perhaps all, of the settlement.

The fort is the only structure whose site has been located exactly. After intensive archeological studies and excavations from 1936 to 1948, National Park Service archeologists had found enough evidence of the original moat to justify reconstruction in 1950. Among the many artifacts recovered during excavation were a wrought iron sickle, an Indian pipe, and metal counters used in accounting. The fort, which originally commanded a good view of the sound, was reconstructed in the same way it was built in 1585. Workers dug out the moat along its original lines throwing the dirt inward to form a parapet that enclosed approximately 50 feet square The fort was essentially a square with pointed bastions on two sides and an octagonal bastion on the third. It is conjectured that the houses would have been built near the road leading from the fort entrance.

About Your Visit

(click for larger map) |

Reconstructions, exhibits, live drama, and talks by park interpreters give visitors to Fort Raleigh National Historic Site a richer understanding of the people who backed the colony from the safety of England and of those who lived and died at this site.

At the visitor center, the Elizabethan Room features the original oak paneling and stone fireplace from a 16th-century house of the kind lived in by the Roanoke colony investors. Also displayed are artifacts from the site exhibits on the colonists and Elizabethan life, and copies of the John White watercolors. A short film relates the story of both attempts to establish colonies.

The Lost Colony, which has been running since 1937, combines drama, music, and dance to tell the story of the ill-fated 1587 Roanoke colony. Pulitzer prize-winning dramatist Paul Green built this semi-fictional story from firsthand accounts. The play is produced each summer in the outdoor Waterside Theater by the Roanoke Island Historical Association Dates and hours are fixed by that organization.

The Elizabethan Gardens were created by the Garden Club of North Carolina as a memorial to the first colonists and as an example of the gardens that graced the estates of the wealthy backers of the colony. Visitors enter through a replica of a Tudor gate house and wander through a rich array of flowers that bloom throughout the year.

For Your Safety

Don't allow your visit to be spoiled by an accident. Every effort has

been made to provide for your safety, but there are still hazards

requiring your alertness Please use common sense and caution.

Source: NPS Brochure (2008)

|

Establishment Fort Raleigh National Historic Site — April 5, 1941 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Acoustic Monitoring Report, Fort Raleigh National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/NSNS/NRR-2015/1067 (Scott D. McFarland, October 2015)

Coastal Hazards & Sea-Level Rise Asset Vulnerability Assessment for Outer Banks (OBX) Group: Cape Hatteras National Seashore, Wright Brothers National Memorial and Fort Raleigh National Historic Site NPS 910/154048 (K. Peek, B. Tormey, H. Thompson, R. Young, S. Norton, J. McNamee and R. Scavo, May 2018)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Fort Raleigh National Historic Site (May 2010)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Fort Raleigh National Historic Site (2022)

Deciphering the Roanoke Mystery (lebame houston and Douglas Stover, eds., 2015)

Fort Raleigh National Historic Site: Historic Handbook #16 (Charles W. Porter, III, 1952)

Fort Raleigh National Historic Site: Historic Handbook #16 (HTML edition) (Charles W. Porter, III, 1952, reprint 1965)

Foundation Document, Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, North Carolina (July 2017)

Foundation Document Overview, Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, North Carolina (January 2017)

Historic Resource Study: Fort Raleigh National Historic Site (Christine Treballas and William Chapman, November 1999)

Inventory of Coastal Engineering Projects in Fort Raleigh National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRTR-2013/704 (Kate Dallas, Michael Berry and Peter Ruggiero, March 2013)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Lane's New Fort in Virginia/Cittie of Raleigh (Ronald G. Warfield, November 20, 1976)

Newsletter (Cape Chronicle Newsletter)

2018: July 26 • August 2 • August 9 • August 15 • August 23 • August 30 • September 7 • September 20 • September 28 • October 4 • October 15 • October 26 • November 1 • November 8 • November 16 • November 21 • November 28 • December 13

2019: March 14 • March 21 • March 29 • April 5 • April 11 • April 19 • April 24 • May 2 • May 8 • May 15 • May 23 • May 30 • June 6 • June 12 • June 20 • July 3 • July 11 • July 18 • July 26 • August 1 • August 8 • August 15 • August 22 • August 29 • September 26 • October 4 • October 10 • October 23 • October 30 • December 5

2020: February 20 • March 3 • April 9 • April 15 • April 27 • May 22 • May 27 • June 11 • June 25 • July 9 • July 21 • August 20 • September 3 • September 10 • October 8 • October 15 • October 21 • November 5 • November 20

2021: March 3 • April 22 • April 29 • May 5 • May 13 • May 20 • May 27 • June 17 • June 28 • July 22 • August 6 • August 19 • August 26 • September 6 • September 15 • November 22

2022: February 11 • February 24 • March 21 • April 8 • April 11 • April 29 • May 5 • May 27 • June 30 • July 29 • August 25 • September 12

2023: January 11 • January 25 • January 30 • February 9 • February 23 • March 8 • March 23 • April 10 • April 25 • May 22 • June 13 • June 23

2024: April 30 • May 9 • May 23 • June 28

Outer Banks Group Business Plan — Fiscal Year 2001 (2002)

Park Newspaper (In The Park): Summer 1983 • Summer 2000 • Summer 2009 • 2020 • 2022 • 2023 • 2024

Preserving the Mystery: An Administrative History of Fort Raleigh National Historic Site (Cameron Binkley and Steven Davis, November 2003)

Pilgrimage to Old Fort Raleigh on Roanoke island, North Carolina, August 20, 1587-May 20, 1908 (Thomas P. Noe, ed., 1908)

Search for the Cittie of Ralegh, Archeological Excavations at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, North Carolina Archeological Research Series No. 6 (Jean Carl Harrington, 1962)

Secrets in the Sand: Archeology at Fort Raleigh — Archeological Resource Study (2011)

Spain and Roanoke Island Voyages: Inventory of Sources Related to Early English and Spanish Voyages to North America in Spanish Archives (Milagros Flores, 2010)

Special History Study: Roanoke Island 1865-1940 (Brian T. Crumley, 2005)

State of the Park Report, Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, North Carolina State of the Park Series No. 34 (2016)

The Finding of Fort Raleigh (J.C. Harrington, extract from Southern Indian Studies, Vol. 1 No. 1, April 1949)

The Manufacture and Use of Bricks at the Raleigh Settlement on Roanoke Island (J.C. Harrington, extract from North Carolina Historical Review, Vol. XLIV No. 1, January 1967)

fora/index.htm

Last Updated: 25-Feb-2025