| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

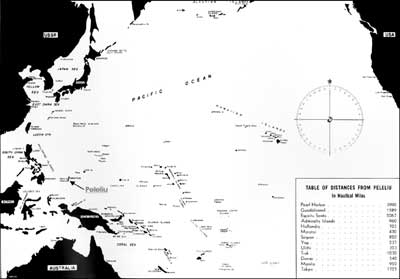

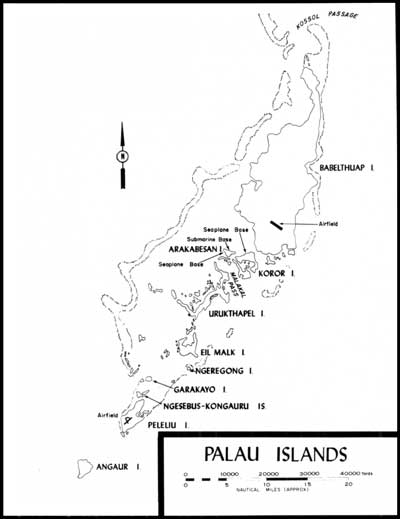

BLOODY BEACHES: The Marines at Peleliu by Brigadier General Gordon D. Gayle, USMC (Ret) On D-Day 15 September 1944, five infantry battalions of the 1st Marine Division's 1st, 5th, and 7th Marines, in amphibian tractors (LVTs) lumbered across 600-800 yards of coral reef fringing smoking, reportedly mashed Peleliu in the Palau Island group and toward five selected landing beaches. That westward anchor of the 1,000-mile-long Caroline archipelago was viewed by some U.S. planners as obstacles, or threats, to continued advances against Japan's Pacific empire.

The Marines in the LVTs had been told that their commanding general, Major General William H. Rupertus, believed that the operation would be tough, but quick, in large part because of the devastating quantity and quality of naval gunfire and dive bombing scheduled to precede their assault landing. On some minds were the grim images of their sister 2d Marine Division's bloody assault across the reefs at Tarawa, many months earlier. But 1st Division Marines, peering over the gunwales of their landing craft saw an awesome scene of blasting and churning earth along the shore. Smoke, dust, and the geysers caused by exploding bombs and large-caliber naval shells gave optimists some hope that the defenders would become casualties from such preparatory fires; at worst, they would be too stunned to respond quickly and effectively to the hundreds of on-rushing Marines about to land in their midst. Just ahead of the first wave of troops carrying LVTs was a wave of armored amphibian tractors (LVTAs) mounting 75mm howitzers. They were tasked to take under fire any surviving strongpoints or weapons which appeared at the beach as the following troops landed. And just ahead of the armored tractors, as the naval gunfire lifted toward deeper targets, flew a line of U.S. Navy fighter aircraft, strafing north and south along the length of the beach defenses, parallel to the assault waves, trying to keep all beach defenders subdued and intimidated as the Marines closed the defenses. Meanwhile, to blind enemy observation and limit Japanese fire upon the landing waves, naval gunfire was shifted to the hill massif northeast of the landing beaches.

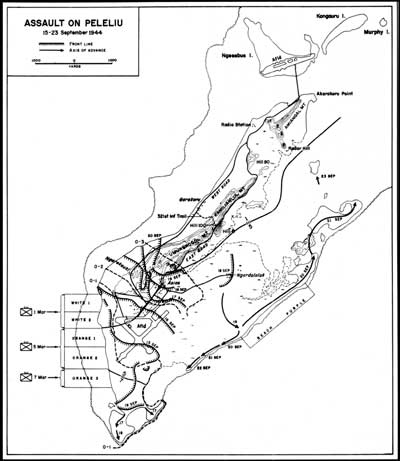

That "massif," later to be called the Umurbrogol Pocket, was the first of two deadly imponderables, as yet unknown to the division commander and his planners. Although General Rupertus had been on temporary duty in Washington during most of his division's planning for the Peleliu landing, he had been well briefed for the operation. The first imponderable involved the real character of Umurbrogol, which aerial photos indicated as a rather gently rounded north-south hill, commanding the landing beaches some 2,000-4,000 yards distant. Viewed in these early photos, the elevated terrain appeared clothed in jungle scrub, which was almost entirely removed by the preparatory bombardment and then subsequent heavy artillery fire directed at it. Instead of a gently rounded hill, the Umurbrogol area was in fact a complex system of sharply uplifted coral ridges, knobs, valleys, and sinkholes. It rose above the level remainder of the island from 50 to 300 feet, and provided excellent emplacements for cave and tunnel defenses. The Japanese had made the most of what this terrain provided during their extensive period of occupation and defensive preparations. The second imponderable facing the Marines was the plan developed by Colonel Kunio Nakagawa, the officer who was to command the force on Peleliu, and his superior, Lieutenant General Sadae Inoue, back on Koror. Their concept of defense had changed considerably from that which was experienced by General Rupertus at Guadalcanal and Cape Gloucester, and, in fact, negated his concept of a tough, but quick campaign. Instead of relying upon a presumed moral superiority to defeat the attackers at the beach, and then to use bushido spirit and banzai tactics to throw any survivors back into the sea, Peleliu's defenders would delay the attacking Marines as long as they could, attempting to bleed them as heavily as possible. Rather than depending upon spiritual superiority, they would combine the devilish terrain with the stubborn, disciplined, Japanese soldiers to relinquish Peleliu at the highest cost to the invaders. This unpleasant surprise for the Marines marked a new and important adjustment to the Japanese tactics which were employed earlier in the war. Little or nothing during the trip into the beaches and the touchdown revealed the character of the revised Japanese tactical plan to the five Marine assault battalions. Bouncing across almost half a mile of coral fronting the landing beaches (White 1 and 2, Orange 1, 2, and 3), the tractors passed several hundred "mines," intended to destroy any craft which approached or ran over them. These "mines" were aerial bombs, set to be detonated by wire control from observation points onshore . However, the preliminary bombardment had so disrupted the wire controls, and so blinded the observers, that the defensive mining did little to slow or destroy the assaulting tractors.

As the tractors neared the beaches, they came under indirect fire from mortars and artillery. Indirect fire against moving targets generates more apprehension than damage, and only a few vehicles were lost to that phase of Japanese defense. Such fire did, however, demonstrate that the preliminary bombardment had not disposed of all the enemy's heavy fire capability. More disturbingly, as the leading waves neared the beaches, the LVTs were hit by heavy enfilading artillery and antiboat gun fire coming from concealed bunkers on north and south flanking points. The defenses on the left (north) flank of Beach White 1, assaulted by the 3d Battalion, 1st Marines (Lieutenant Colonel Stephen V. Sabol), were especially deadly and effective. They disrupted the critical regimental and division left flank. Especially costly to the larger landing plan, these guns shortly thereafter knocked out tractors carrying important elements of the battalion's and the regiment's command and control personnel and equipment. The battalion and then the regimental commander both found themselves ashore in a brutally vicious beach fight, without the means of communication necessary to comprehend their situations fully, or to take the needed remedial measures. The critical mission to seize the "The Point" dominating the division left flank had gone to one of the 1st Regiment's most experienced company commanders: Captain George P. Hunt, a veteran of Guadalcanal and New Britain, (who, after the war, became a long-serving managing editor of Life magazine). Hunt had developed plans involving specific assignments for each element of his company. These had been rehearsed until every individual knew his role and how it fit into the company plan. Each understood his mission's criticality.

D-Day and H-Hour brought heavier than expected casualties. One of the company's platoons was pinned down all day in the fighting at the beach. The survivors of the rest of the company wheeled left, as planned, onto the flanking point. Moving grimly ahead, they pressed assaults upon the many defensive emplacements. Embrasures in the pillboxes and casements were blanketed with small-fire arms and smoke, then attacked with demolitions and rifle grenades. A climax came at the principal casement, from which the largest and most effective artillery fire had been hitting LVTs on the flanks of following landing waves. A rifle grenade hit the gun muzzle itself, and ricocheted into the casement, setting off explosions and flames. Japanese defenders ran out the rear of the blockhouse, their clothing on fire and ammunition exploding in their belts. That flight had been anticipated, and some of Hunt's Marines were in position to cut them down. At dusk, Hunt's Company K held the Point, but by then the Marines had been reduced to platoon strength, with no adjacent units in contact. Only the sketchy radio communications got through to bring in supporting fires and desperately needed re-supply. One LVT got into the beach just before dark, with grenades, mortar shells, and water. It evacuated casualties as it departed. The ammunition made the difference in that night's furious struggle against Japanese determined to recapture the Point.

The next afternoon, Lieutenant Colonel Raymond G. Davis' 1/1 moved its Company B to establish contact with Hunt, to help hang onto the bitterly contested positions. Hunt's company also regained the survivors of the platoon which had been pinned at the beach fight throughout D-Day. Of equal importance, the company regained artillery and naval gunfire communications, which proved critical during the second night. That night, the Japanese organized another and heavier — two companies — counterattack directed at the Marines at the Point. It was narrowly defeated. By mid-morning, D plus 2, Hunt's survivors, together with Company B, 1/1, owned the Point, and could look out upon some 500 Japanese who had died defending or trying to re-take it.

To the right of Puller's struggling 3d Battalion, his 2d Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Russell E. Honsowetz commanding, met artillery and mortar opposition in landing, as well as machine-gun fire from still effective beach defenders. The same was true for 5th Marines' two assault battalions, Lieutenant Colonel Robert W. Boyd's 1/5 and Lieutenant Colonel Austin C. Shofner's 3/5, which fought through the beach defenses and toward the edge of the clearing looking east over the airfield area. On the division's right flank, Orange 3, Major Edward H. Hurst's 3/7 had to cross directly in front of a commanding defensive fortification flanking the beach as had Marines in the flanking position on the Point. Fortunately, it was not as close as the Point position, and did not inflict such heavy damage. Nevertheless, its enfilading fire, together with some natural obstructions on the beach caused Company K, 3/7, to land left of its planned landing beach, onto the right half of beach Orange 2, 3/5's beach. In addition to being out of position, and out of contact with the company to its right, Company K, 3/7, became intermingled with Company K, 3/5, a condition fraught with confusion and delay. Major Hurst necessarily spent time regrouping his separated battalion, using as a coordinating line a large anti-tank ditch astride his line of advance. His eastward advance then resumed, somewhat delayed by his efforts to regroup.

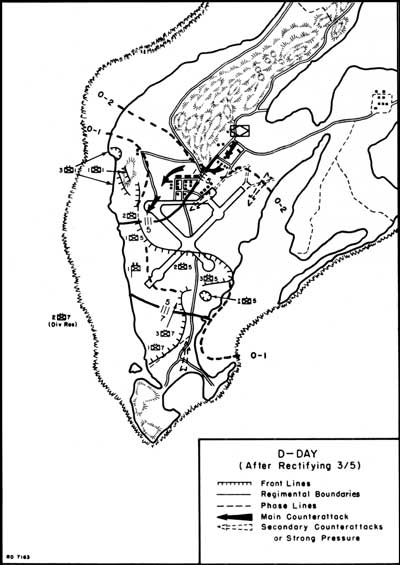

Any delay was anathema to the division commander, who visualized momentum as key to his success. The division scheme of maneuver on the right called for the 7th Marines (Colonel Herman H. Hanneken) to land two battalions in column, both over Beach Orange 3. As Hurst's leading battalion advanced, it was to be followed in trace by Lieutenant Colonel John J. Gormley's 1/7. Gormley's unit was to tie into Hurst's right flank, and re-orient southeast and south as that area was uncovered. He was then to attack southeast and south, with his left on Hurst's right, and his own right on the beach. After Hurst's battalion reached the opposite shore, both were to attack south, defending Scarlet 1 and Scarlet 2, the southern landing beaches. At the end of a bloody first hour, all five battalions were ashore. The closer each battalion was to Umurbrogol, the more tenuous was its hold on the shallow beachhead. During the next two hours, three of the division's four remaining battalions would join the assault and press for the momentum General Rupertus deemed essential.

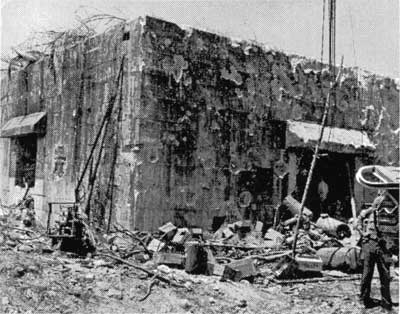

Following close behind Sabol's 3/1, the 1st Marines' Colonel Puller landed his forward command group. As always, he was eager to be close to the battle, even if that location deprived him of some capacity to develop full supporting fires. With limited communications, and now with inadequate numbers of LVTs for follow-on waves, he struggled to ascertain and improve his regiment's situation. His left unit (Company K, 3/1) had two of its platoons desperately struggling to gain dominance at the Point. Puller's plan to land Major Davis' 1st Battalion behind Sabol's 3/1, to reinforce the fight for the left flank, was thwarted by the H-hour losses in LVTs. Davis' companies had to be landed singly and his battalion committed piecemeal to the action. On the regiment's right, Honsowetz' 2/1 was hotly engaged, but making progress toward capture of the west edges of the scrub which looked out onto the airfield area. He was tied on his right into Boyd's 1/5, which was similarly engaged. In the beachhead's southern sector, the landing of Gormley's 1/7 was delayed somewhat by its earlier loses in LVTs. That telling effect of early opposition would be felt throughout the remainder of the day. Most of Gormley's battalion landed on the correct (Orange 3) beach, but a few of his troops were driven leftward by the still enfilading fire from the south flank of the beach, and landed on Orange 2, in the 5th Marines' zone of action. Gormley's battalion was brought fully together behind 3/7 however, and as Hurst's leading 3/7 was able to advance east, Gormley's 1/7 attacked southeast and south, against prepared positions. Hanneken's battle against heavy opposition from both east and south developed approximately as planned. Suddenly, in mid-afternoon, the opposition grew much heavier. Hurst's 3/7 ran into a blockhouse, long on the Marines' map, which had been reported destroyed by pre-landing naval gunfire. As a similar situation later met on Puller's inland advance, the blockhouse showed little evidence of ever having been visited by heavy fire. Preparations to attack and reduce this blockhouse further delayed the 7th Marines' advance, and the commanding general fretted further about loss of momentum.

|