| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

BLOODY BEACHES: The Marines at Peleliu by Brigadier General Gordon D. Gayle, USMC (Ret) Encirclement of Umurbrogol and Seizure of Northern Peleliu A plan to encircle the Pocket, and deny reinforcement to northern Peleliu was immediately formulated. General Rupertus' staff was closely attended by selected III Corps staff officers, and General Geiger also was present. The plan called for two regiments to move up the West Road, the Army 321st Infantry leading in the attack, and the 5th Marines following. The Marines were to pass through the Army unit after it had gone beyond the Pocket on its right, and the 5th would continue then to take northern Peleliu and Ngesebus. The 321st RCT, by now battle tested, was tasked to push up the West Road, alongside and just atop the western edge of coral uplift which marked the topographical boundary between the flat western plain, and the uplifted coral "plateau." That plateau, about 300 yards west to east, constituted the western shoulder of the Pocket. The plateau rose some 30-80 feet above the West Road. Its western edge, or "cliff," was a jumble of knobs and small ridges which dominated the West Road, and would have to be seized and cleared to permit unharrassed use of the road.

Once the 321st RCT was past this up-lift, and the Pocket which it bounded, it was to probe east in search of any routes east through the 600 yards necessary to reach the eastern edge of that portion of Peleliu. Any opportunities in that direction were to be exploited to encircle the Pocket on the north. Behind the 321st RCT, the 5th Marines followed, pressed through, and attacked into northern Peleliu. Hanneken's 7th Marines relieved the 1st, which was standing down to the eastern peninsula, also relieving the 5th Marines of their then-passive security role. The 5th was then tasked to capture northern Peleliu, and to seize Ngesebus-Kongauru. This maneuver would involve the use of the West Road, first as a tactical route north, then as the line of communications for continued operations to the north. The road was comparatively "open" for a distance about halfway, 400 yards, to the northern limit of the Pocket, and paralleled by the ragged "cliff" which constituted the western shoulder of the up-lifted "plateau." That feature was no level plateau, but a veritable moonscape of coral knobs, karst, and sinkholes. It had no defined ridges or pattern. The sinkholes varied from room-size to house-size, 10 to 30 feet in depth, and jungle- and vine-covered. The "plateau" was generally 30 to 100 feet above the plain of the road. Some 200-300 yards further to the east, it dropped precipitously off into a sheer cliff, called the China Wall by those Marines who looked up to it from the southern and eastern approaches to the Pocket. To them, that wall was the western edge of the Pocket and the coral "plateau" was a virtually impassable shoulder of the Pocket. The plateau was totally impenetrable by vehicles. The coral sinkholes and uplifted knobs forced any infantry moving through to crawl, climb, or clamber down into successive small terrain compartments of rough and jagged surfaces. Evacuating any casualties would involve unavoidable rough handling of stretchers and their wounded passengers. The area was occupied and defended by scattered small units and individuals who did not sally forth, and who bitterly resisted movement into their moonscape. When Americans moved along the West Road, these Japanese ignored individuals, took under fire only groups or individuals which appeared to them to be rich targets.

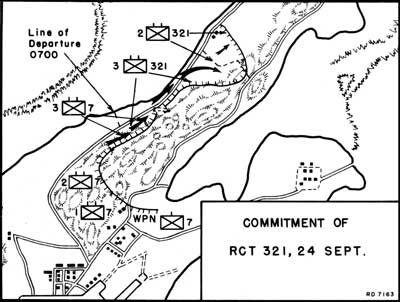

The only tactical option along the West Road was to seize and hold the coral spires and cliffs commanding the road, and to defend such positions against infiltrators. Once those heights were seized, troop units and trucks could move along West Road. Until seized, the "cliff" offered concealment and some cover to occupying Japanese. Until those cliff positions were seized and held, the Japanese therein could be only temporarily silenced by heavy firepower. Until they were driven from their commanding positions, the road could not be treated as truly open. Those terrain conditions existed for three-quarters of a mile along the West Road. There, abreast the north end of the Pocket, the plateau of coral sinkholes merged into a more systematic group of limestone ridges. These ridges trended slightly north east, broadening the coastal strip to an east-west width of 200 to 400 yards. Into that milieu, the 321st RCT was launched on 23 September, behind an hour-long intensive naval gunfire and artillery preparation against the high ground commanding the West Road. The initial Army reconnaissance patrols moved generally west of the road, somewhat screened from any Japanese still on the "cliff" just east of the road by vegetation and small terrain features. These tactics worked until larger units of the 2d Battalion, 321st, moved out astride the West Road. Then they experienced galling fire from the heights above the road. The 321st's 2d Battalion had relieved 3d Battalion, 1st Marines, along an east-west line across the road, and up onto the heights just above the road. Near that point, the 1st Marines had been tied into the forward left flank of 3d Battalion, 7th Marines. The orders for the advance called for 3/7 to follow behind the elements of 2/321, along the high ground as the soldiers seized the succeeding west edge of the cliff and advanced northward. However, the advanced elements along the ridge were immediately out-paced by the other 2/321 elements in the flat to their west. Instead of fighting north to seize the ridge, units responsible for that cliff abandoned it, side stepping down to the road. They then advanced along the road, and soon reported that 3/7 was not keeping contact along the high ground.

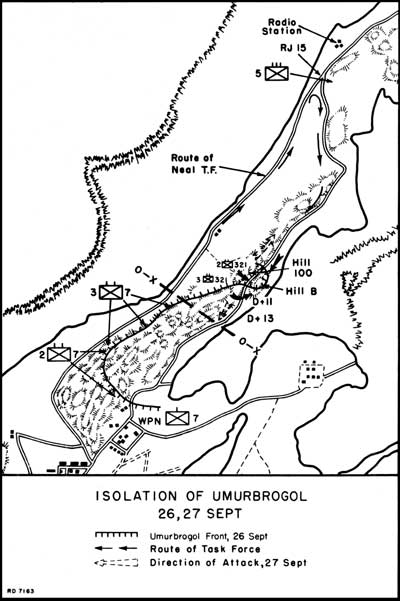

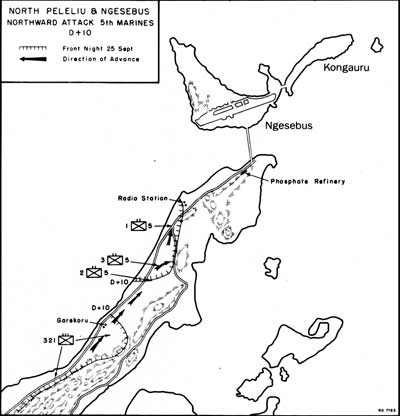

On orders from Colonel Hanneken, the 7th Marines' commanding officer, 3/7 then captured the high ground which 2/321 had abandoned, but at a cost which did little for inter-service relations. Thereafter, 3/7 was gradually further committed along the ridge within the 321st zone of action. This of course stretched 3 / 7, which still had to maintain contact on its right in the 7th Marines' zone, generally facing the southern shoulders of the Umurbrogol Pocket. Further north, as the 321st pressed on, it was able to regain some of the heights above its axis of advance, and thereafter held onto them. Abreast the northern end of Umurbrogol Pocket, where the sink hole terrain blended into more regular ridgelines, the 321st captured parts of a key feature, Hill 100. Together with an adjacent hill just east of East Road, and designated Hill B, that position constituted the northern cap of the Umurbrogol Pocket. Seizing Hill B, and consolidating the partial hold on Hill 100 would occupy the 321st for the next three days. As the regiment probed this eastern path across the north end of Umurbrogol, it also pushed patrols north up the West Road. In the vicinity of the buildings designated "Radio Station," it reached a promising road junction. It was in fact the junction of West and East Roads. Colonel Robert F. Dark, commanding officer of RCT 321, determined to exploit that route, back south, to add a new direction to his attack upon Hill 100/Hill B. He organized a mobile task force heavy in armor and flamethrowers, designated Task Force Neal, named for Captain George C. Neal. He sent it circling southeast and south to join 2/321's efforts at the Hill 100/Hill B scene. Below that battle, the 7th Marines continued pressure on the south and east fronts of the Pocket, but still attacking south to north. As those efforts were underway, the 5th Marines was ordered into the developing campaign for northern Peleliu. Now relieved by the 1st Marines of its passive security mission on the eastern peninsula and its near by three small islands, the 5th moved over the West Road to side-step the 321st action and seize northern Peleliu. Having received the division order at 1100, the 5th motored, marched, and waded (off the north eastern islets) to and along the West Road. By 1300, its 1st Battalion was passing through the 321st lines at Garekoru, moving to attack the radio station installations discovered by 321st patrols the previous afternoon. In this area, the 5th Marines found flat ground, some open and some covered with palm trees. The ground was broken by the familiar limestone ridges, but with the critical tactical difference that most of the ridges stood alone. Attackers were not always exposed to flanking fires from mutually supporting defenses in adjacent and/or parallel ridges, as in the Umurbrogol. The Japanese had prepared the northern ridges for defense as thoroughly as they had done in the Umurbrogol, with extensive tunnels and concealed gun positions. However, the positions could be attacked individually with deliberate tank, flamethrower, and demolition tactics. Further, it developed that the defenders were not all trained infantrymen; many were from naval construction units.

On the U.S. side of the fight, a weighty command factor shaped the campaign into northern Peleliu. Colonel Harold D. "Bucky" Harris was determined to develop all available firepower fully before sending his infantry into assault. His aerial reconnaissance earlier had acquainted him with an understanding of the terrain. This knowledge strengthened his resolve to continue using all available firepower and employing deliberate tactics as he pursued his regiment's assigned missions. On the afternoon of 25 September, 1/5 seized the Radio Station complex, and the near portion of a hill commanding it. When 3/5 arrived, it was directed to seize the next high ground to the east of 1/5's position. Then when 2/5 closed, it tied in to the right of 3/5's position, and extended the regimental line back to the beach. This effectively broke contact with the 321st operations to the south, but fulfilled Colonel Harris' plans to advance north as rapidly as possible, without over-extending his lines. By suddenly establishing this regimental "beachhead," the 5th Marines had surprised the defenders with strong forces challenging the cave defenses, and in position to engage them fully on the next day.

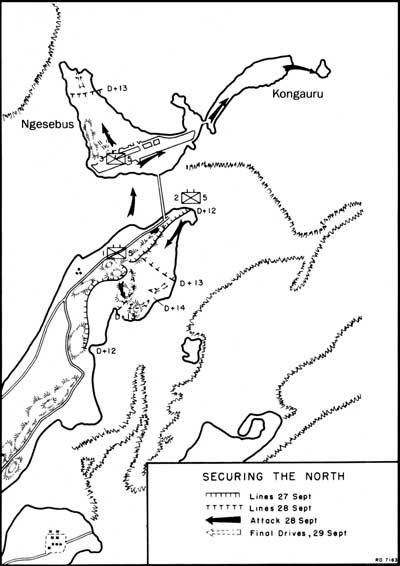

The following day, 26 September, as the 321st launched its three-pronged attack against Hill 100/Hill B (northern cap of the Umurbrogol Pocket) and the 5th Marines attacked four hills running east to west across Peleliu, dubbed Hills 1, 2, 3, and Radar Hill in Hill Row. The row was perpendicular to and south of the last northern ridge, Amiangal Mountain. These hills and the ridge were defended by some 1,500 infantry, artillerymen, naval engineers, and the shot-up reinforcing infantry battalion which landed the night of 23 September, in caves and interconnected tunnels within the ridge and the hills. As the fight for Hill Row developed, Colonel Harris had his 2d Battalion side-step west of Hill Row and begin an attack on the Amiangal ridge to the north. Before dark, the 2d Battalion had taken the southern end and crest of the ridge, but was under severe fire from cave positions in the central and northwestern slopes of the ridge. What was not yet appreciated was that the Marines were confronting the most comprehensive set of caves and tunnels on Peleliu. They were trying to invade the home (and defensive position) of a long-established naval construction unit most of whose members were better miners than infantrymen. As dark fell, the 2d Battalion cut itself loose from the units to its south, and formed a small battalion beachhead for the night.

The next morning, as the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, tried to move along the route leading to the northern nose of Amiangal Ridge, it ran into a wide and deep antitank ditch which denied the attacking infantry the close tank support they had so successfully used earlier. At this point, the 5th Marines command asked, again, for point-blank artillery. This time, division headquarters responded favorably. During the night of 27 September Major George V. Hanna's 8th 155mm Gun Battalion moved one of its pieces into position in 2/5's sector. The gun was about 180 yards from the face of Amiangal Ridge. The sight of that threat at dawn elicited enemy machine-gun fire which inflicted some casualties upon the artillery men. This fire was quickly suppressed by Marine infantry fire, and then by the 155mm gun itself. Throughout the morning, the heavy 155mm fire played across the face of Amiangal Ridge, destroying or closing all identified caves on the west face, except for one. That latter was a tunnel mouth, down at ground level and on the northwestern base of the hill. It was too close to friendly lines to permit the gun to take it under fire. But by then, tanks had neutralized the tunnel mouth, and a tank bulldozer filled in a portion of the anti-tank ditch. This allowed 2/5's tank-infantry teams to close on the tunnel mouth, to blast and bulldoze it closed, and to press on around the northern nose of Amiangal. Simultaneously, Marines swept over the slopes above the tunnel and "seized" the crest of the small mountain. The term seizure is qualified, for although 2/5 held the outside of the hill, the stubborn Japanese defenders still held the inside. A maze of inter connected tunnels extended through out the length and breadth of the Amiangal Ridge. From time to time the Japanese inside the mountain would blast open a previously closed cave or tunnel mouth, and sortie to challenge the Marines. Notwithstanding their surprise effect, these counterattacks provided a rare and welcome opportunity for the Marines actually to see their enemy in daylight. Such tactics were inconsistent with the general Japanese strategy for Peleliu, and somewhat shortened the fight for the northern end of the island.

As that fighting progressed, the 5th Marines assembled its 3d Battalion, supporting tanks, amphibian tractors, and the entire panoply of naval gunfire, and air support to launch a shore-to-shore operation to seize Ngesebus and Kongauru, 600 yards north of Peleliu, on 28 September. There followed an operation which was "made to look easy" but which in fact involved a single, reinforced (but depleted) battalion against some 500 prepared and entrenched Japanese infantry. For some 35 hours, the battalion conducted the most cost-effective single battalion operation of the entire Peleliu campaign. Much of the credit for such effectiveness was due to supporting aviation. VMF-114, under Major Robert F. "Cowboy" Stout, had landed on Peleliu's air strip just three days prior to this landing, and immediately undertook its primary service mission: supporting Marine ground operations. The Ngesebus landing was the first in the Pacific War for which the entire air support of a landing was provided by Marine aviation. As the LVTs entered the water from Peleliu's shore, the naval gun fire prematurely lifted to the alarm of the assault troops. Stout's pilots immediately recognized the situation, resumed their strafing of Ngesebus until the LVTs were within 30 yards of the beach. They flew so low that the watching Marines "expected some of them to shoot each other down by their ricochets." This action so kept the Japanese defenders down that the Marines in the leading waves were upon them before they recovered from the shock of the strafing planes.

The 3d Battalion got ashore with no casualties. Thus enabled to knock out all the Japanese in beach defenses immediately, it turned its attention to the cave positions in the ridges and blockhouses. The ridges here, as with those on northern Peleliu, stood individually, not as part of complex ridge systems. This denied their defenders opportunities for a mutual defense between cave positions. The attacking companies of 3/5 could use supporting tanks and concentrate all fire means upon each defensive system, without being taken under fire from their flanks and rear. By nightfall on 28 September, 3/5 had overrun most of the opposition. On 29 September, there was a day of mopping up before Ngesebus was declared secure at 1500. As planned, the island was turned over to 2/321, and 3/5 was moved to division reserve in the Ngardololok area. Seizure of Ngesebus by one depleted infantry battalion gave a dramatic illustration of an enduring principle of war: the effective concentration of means. To support that battalion, General Rupertus concentrated the bulk of all his available firepower: a battleship; two cruisers; most of the divisional and corps artillery; virtually all of the division's remaining armor; armored amphibian tractors; all troop-carrying amphibian tractors; and all Marine aviation on Peleliu.

Such concentrated support enabled the heavily depleted 3d Battalion, 5th Marines, to quickly seize Ngesebus, destroying 463 of Colonel Nakagawa's battle-hardened and well-emplaced warriors in 36 hours, at a cost of 48 American casualties. Other maneuver elements on Peleliu also were attacking during those 36 hours, but at an intensity adjusted to the limited support consequent upon General Rupertus' all-out support of the day's primary objective. As 3/5 was clearing Ngesebus, the rest of the 5th Marines was fighting the Japanese still in northeast Peleliu. After capturing Akarakoro Point beyond Amiangal Mountain, 2/5 turned south. It swept through the defenses east of that mountain with demolitions and flamethrowers, then moved south toward Radar Hill, the eastern stronghold of Hill Row. That feature was under attack from the south and west by 1/5. After two days, the two battalions were in command of the scene, at least on the topside of the hills. Inside there still remained stubborn Japanese defenders who continued to resist the contest for Radar Hill, as did the defenders within Amiangal Mountain's extensive tunnels. All could be silenced when the cave or tunnel mouths were blasted closed. As these operations were in progress, the 321st at the north end of Umurbrogol completed seizing Hills 100 and Hill B, then cleared out the ridge (Kamilianlul Mountain) and road north from there to the area of 5th Marines operations. On 30 September the 321st relieved the 1st and 2d Battalions of the 5th Marines in northern Peleliu. That regiment reassembled in the Ngardololok area, before it became once more necessary to commit it to the Umurbrogol Pocket.

|