| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

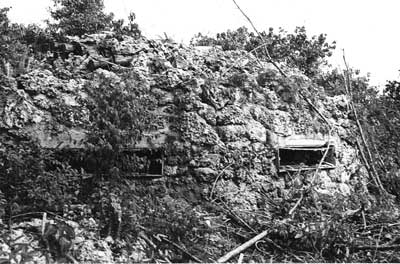

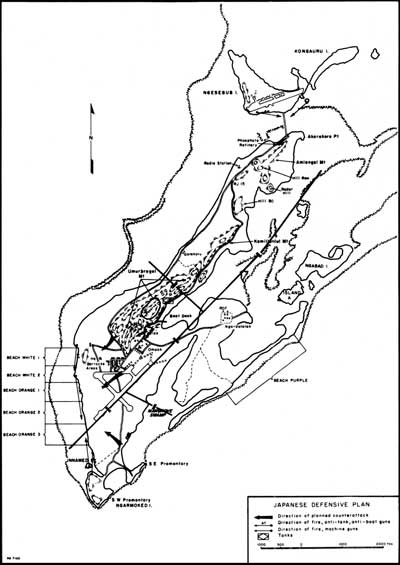

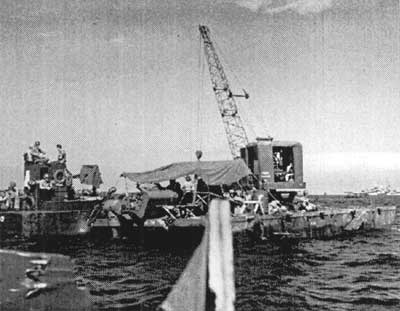

BLOODY BEACHES: The Marines at Peleliu by Brigadier General Gordon D. Gayle, USMC (Ret) The Assault in the Center As the 1st Marines battled to se cure the left flank, and as the 7th Marines fought to isolate and then reduce the Japanese defenses in the southern end of Peleliu, the 5th Marines, Colonel Harold D. Harris commanding, was charged to drive across the airfield, cut the island in two, and then re-orient north and drive to secure the eastern half of the island. Shortly after the scheduled H plus one schedule, the 2d Battalion, 5th Marines, Major Gordon D. Gayle commanding, landed over Beach Orange 2, in trace behind 3/5. It moved directly east, through the dunes and scrub jungle, into and out of the antitank barrier, and to the west edge of the clearing surrounding the airfield. Passing through the lines of 3/5, Gayle's battalion attacked west against scattered resistance from dug-outs and bomb shelters near the southern end of the airfield, and through the scrub area slightly farther south. The 3d Battalion's mission was to clear that scrub, maintaining contact with 3/7 on its right, while 2/5 was to drive across the open area to reach the far side of the island. Advancing in its center and right, 2/5 battled completely across the island by mid-afternoon, echeloned its left rearward to keep contact with 1/5, and moved to reorient its attack northward. The 2d Battalion's right flank tied for a while into 3/5 in the woods to the south of the airfield, but then lost contact. By this time, the antitank ditch along the center and right of Orange Beaches 1 and 2 was notable for the number of command posts located along its length. Shofner's 3/5 was there, as was Harris' 5th Marines command post. Then an advance element of the division command post under Brigadier General Oliver P. Smith, the assistant division commander, landed and moved into the antitank ditch within sight of the airfield clearing area. Simultaneously, important support weapons were moving ashore. The 1st Tank Battalion's M-48A1 Sherman medium tanks, one-third of which had been left behind at the last moment because of inadequate shipping, were landed as early as possible, using a novel technique to cross the reef. This tank landing scheme was developed in anticipation of early Japanese use of their armor capability.

Movement of this fire and logistical support material onto a beach still close to, and under direct observation from, the commanding Umurbrogol heights was an inescapable risk man dated by the Peleliu terrain. So long as the enemy held observation from Umurbrogol over the airfield and over the beach activity, there was no alternative to driving ahead rapidly, using such fire support as could be mustered and coordinated. Continuing casualties at the beaches had to be accepted to support the rapid advance. The commanding general's concern for early momentum appeared to be eminently correct. Units on the left had to assault toward the foot of Umurbrogol ridges, and quickly get to the commanding crests. In the center, the 5th Marines had to make a fast advance to secure other possible routes to outflank Umurbrogol. In the south, the 7th Marines had to destroy immediately those now cut-off forces before becoming freed to join the struggle against central Peleliu. The movement of the 5th Marines across the airfield and to the western edge of the lagoon separating the air field area from the eastern peninsula (Beach Purple), created a line of attacking Marines completely across that part of the island oriented both east and north, toward what was believed to be the major center of Japanese strength. The 7th Marines, pushing east and south, completed splitting the enemy forces. Colonel Hanneken's troops, fully engaged, were generally concealed against observation from the enemy still north of the airfield and from the heights of Umurbrogol. There was a gap between the 5th's right and the 7th's left, but it did not appear to be in a critical sector.

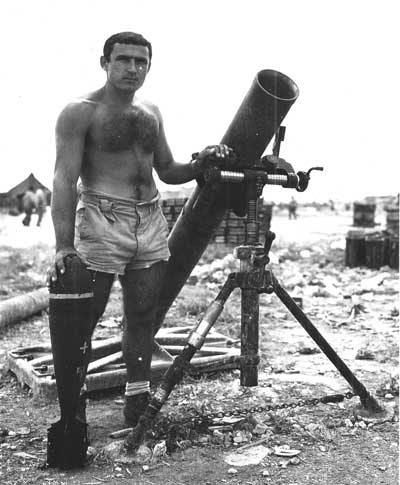

Nevertheless, it was by now apparent that the D-Day phase-line objectives were not going to be met in either the south or the north. Alarmed at the loss of the desired momentum, General Rupertus began committing his reserve. First, he ordered the division reconnaissance company ashore, then, pressing commanders already on the island, he ordered his one remaining uncommitted infantry battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Spencer S. Berger's 2/7, to land. No commander ashore felt a need for 2/7, but Colonel Hanneken said he could find an assembly area where it would not be in the way. General Rupertus ordered it to land, remarking to his staff that he had now "shot his bolt." Ashore, it was apparent that what was needed on this hectic beachhead was not more troops, but more room in which to maneuver and more artillery. General Rupertus began to make plans to land himself and the main elements of his command group. Advice from the ADC ashore, and his chief of staff, Colonel John T. Selden, convinced Rupertus to stay on the flagship. He compromised that decision by ordering Colonel Selden ashore. By now, the shortage of LVTs was frustrating the timely landing of following waves. In consequence, neither Selden's small CP group, nor Berger's 2/7, could get past the transfer line in their landing craft, and had to return to their ships despite their orders to land. Into this division posture, at about 1650, Colonel Nakagawa launched his planned tank-infantry counterattack. All Marine commanders had been alerted to the Japanese capability to make an armored attack on D Day, and were well prepared. The attack emerged from the area north of the airfield and headed south, generally across the front of the 1st Marines' lines on the eastern edge of the airfield clearing. The attack moved directly into the 5th Marines' sector where Boyd's 1/5 was set in, and stretched across the southern area of the airfield. Marines in 2/1 and 1/5 took the attackers under fire, infantry and tanks alike. A bazooka gunner in 2/1's front hit two of the tanks. The commanding officer of 1/5 had his tanks in defilade, just behind his front lines. They opened up on the Japanese armor, which ran through the front lines and virtually into his forward command group. Boyd's lines held fast, taking the attackers, infantry and tanks alike, under fire with all available weapons.

Major John H. Gustafson, in 2/5's forward command post mid-way across the airfield, had his tank platoon close at hand. Although the enemy had not yet come into his zone of action, he launched the platoon of tanks into the melee. Accounts vary as to just who shot what, but in a very few minutes it was all over. The attacking tanks were all destroyed, and the Japanese infantry literally blown away. Colonel Nakagawa's attack was courageous, but proved to be a total failure. Even where the tanks broke through the Marine lines, they induced no Marine retreat. Instead, the Japanese armor became the focus of antitank fire of every sort and caliber. The light Japanese tanks were literally blown apart. More than 100 were reported destroyed. That figure, of course, reflected the amount of fire directed their way; each Marine grenadier, antitank gunner, and tanker thought he had killed the tank at which he shot, and so reported. With the counterattack over and the Japanese in apparent disarray, 2/5 immediately resumed its attack, moving north along the eastern half of the airfield. The battalion advanced halfway up the length of the airfield clearing before it stopped to organize for the night. It was the maximum advance of the day, over the most favorable terrain in the division front. It provided needed space for artillery and logistic deployment to support the continuation of the attack the next day.

However, that relatively advanced position had an open right, south, flank which corresponded to a hole in the regimental command structure. At that stage, 3/5 was supposed to maintain the contact between north-facing 2/5 and south-oriented 3/7. But 3/5's battalion command and control had been completely knocked out by 1700. The battalion executive officer, Major Robert M. Ash, had been killed earlier in the day by a direct hit upon his landing LVT. About the time of the Japanese tank attack, a mortar barrage hit the 3/5 CP in the antitank ditch near the beach, killing several staff and prompting the evacuation of the battalion commander. As of 1700, the three companies of 3/5 were not in contact with each other, nor with the battalions to their right and left.

The 5th Marines commanding officer ordered his executive officer, Lieutenant Colonel Lewis W. Walt, to take command of 3/5 and to redeploy so as to close the gap between 5th and 7th Marines. Major Gayle moved 2/5's reserve company to his right flank and to provide a tie-in position. Walt located and tied in his 3/5 companies to build a more continuous regimental line. By 2230, he had effected the tie-in, just in time. Beginning then, the salient which the 5th Marines had carved between Peleliu's central and southern defenders came under a series of sharp counterattacks that continued throughout the night. The attacks came from both north and south. None of them enjoyed any notable success, but they were persistent enough to require resupply of ammunition to forward companies. Dawn revealed scores of Japanese bodies north of the Marine lines. Elsewhere across the 1st Division's front there were more potentially threatening night counterattacks. None of them succeeded in driving Marines back or in penetrating the lines in significant strength. The most serious attack came against the Company K, 3/1, position on the Point, at the 1st Marines' left. In the south, the 7th Marines experienced significant night attacks from the Japanese battalion opposing it. But the Marines there were in comfortable strength, had communications to bring in fire support, including naval gunfire illumination. They turned back all attacks without a crisis developing.

At the end of the first 12 hours ashore, the 1st Marine Division held its beachhead across the intended front. Only in the center did the depth approximate that which had been planned. The position was strong everywhere except on the extreme left flank. General Smith, from his forward command post was in communication with all three regimental commanders. The report he received from Colonel Puller, on the left, did not afford an adequate perception of 1st Marines tenuous hold on the Point. That reflected Colonel Puller's own limited information. The other two regimental reports reflected the situations adequately. In addition to the three infantry regiments, the 1st Division had almost three battalions of light artillery ashore and emplaced. All 30 tanks were ashore. The shore party was functioning on the beach, albeit under full daylight observation by the enemy and under intermittent enemy fire. The division necessarily had to continue at full press on D plus 1. The objective was to capture the commanding crests on the left, to gain maneuver opportunities in the center, and to finish off the isolated defenders in the south.

At least two colonels on Peleliu ended their work day with firm mis conceptions of their situations, and with correspondingly inaccurate reports to their superiors. At day's end, when General Smith finally got a telephone wire into the 1st Marines' CP, he was told that the regiment had a firm hold on its beachhead, and was approximately on the 0-1 objective line. He was not told about, and Colonel Puller was not fully aware of the gaps in his lines, nor of the gravity of the Company K, 3/1, struggle on the Point, where only 38 Marines were battling to retain the position. Colonel Nakagawa. on the other hand, had reported that the landing attempt by the Marines had been "put to route." Inconsistently, he had also reported that his brave counterattack force had thrown the enemy into the sea.

|