| Marines in World War II Commemorative Series |

|

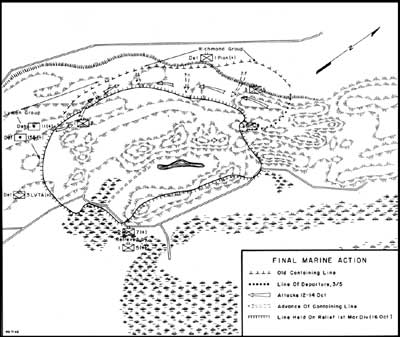

BLOODY BEACHES: The Marines at Peleliu by Brigadier General Gordon D. Gayle, USMC (Ret) Post-assault Operations in the Palaus When on 20 October Major General Mueller became responsible for mopping up on Peleliu, he addressed the tactical problem as a siege situation, and directed his troops to proceed accordingly. Over a period of nearly six weeks, his two regiments, the 322d and 323d Infantry, plus 2/321, did just that. They used sandbags as an assault device, carrying sand up from the beaches and inching the filled sandbags forward to press ever nearer to positions from which to attack by fire the Japanese caves and dug in strong points. They made liberal use of tanks and flamethrowers, even improving upon the vehicle-mounted flamethrower. They thrust a gasoline pipeline forward from a roadbound gasoline truck, thereby enabling them, with booster pumps, to throw napalm hundreds of feet ahead into Japanese defensive areas. Noting the effectiveness of the 75mm pack howitzer which the Marines had wrestled up to Hill 140, they sought and found other sites to which they moved pack howitzers, and from which they fired point-blank into defending caves. To support their growing need for sand bags on ridge-top "foxholes," their engineers strung highlines to transport sand (and ammo and rations) up to such peaks and ridgetops.

Notwithstanding these deliberate siege tactics, the 81st troops still faced death and maiming as they ground down the bitter and stubborn Japanese defenses. The siege of the Umurbrogol Pocket consumed the full efforts of 81st Division's 322d RCT and 323d RCT, as well as 2/321, until 27 November 1944 (D plus 73). This prolonged siege operation was carried on within 25 miles of a much larger force of some 25,000 Japanese soldiers in the northern Palaus. Minor infiltrations aside, those Japanese were isolated by U.S. Navy patrols, and by regular bombing from Marine Aircraft Group 11, operating from Peleliu. Difficult and costly as the American advances were, the Japanese defenders in their underground positions had a similarly demanding and even more discouraging situation. Water was low. Sanitation was crude to nonexistent. Rations were short, and ammunition was even scarcer. As time wore on, some of the Japanese, when afforded opportunity, chose to leave their defenses and undertake futile, usually suicidal night attacks. A very few succeeded in being captured. Toward late November, even Major General Murai apparently came to this point of view. Still not in command, he nevertheless proposed, in a radio message to Lieutenant General Inoue on Koror, a banzai finale for their prolonged defense. But General Inoue turned down the proposal. By this time, Nakagawa's only exterior communications were by radio to Koror. As he had anticipated, all local wire communications had been destroyed. He had issued mission orders to carry his units through the final phase of defense.

As the tanks and infantry carefully pressed their relentless advances, the 81st Division's engineers pressed forward and improved the roads and ramps leading into or toward the heart of the Japanese final position. This facilitated the tank and flamethrower attacks to systematically reduce each cave and position as the infantry pushed its sandbag "fox-holes" forward. On 24 November, Colonel Nakagawa sent his final message to his superior on Koror. He advised that he had burned the colors of the 2d Infantry Regiment. He said that the final 56 men had been split into 17 infiltration parties, to slip through the American positions and to "attack the enemy everywhere." During the night of 24-25 November, 25 Japanese, including two officers, were killed. Another soldier was captured the following morning. His interrogation, together with postwar records and interviews, led to his conclusion that Colonel Nakagawa and Major General Murai died in the CP, in ritual suicide. The final two-day advance of the 81st Division's soldiers was truly and literally a mopping-up operation. It was carefully conducted to search out any holed-up opposition. By mid day on 27 November, the north-moving units, guarded on the east by other Army units, met face-to-face with the battalion moving south, near the Japanese CP later located. The 323d's commander, Colonel Arthur P. Watson, reported to General Mueller that the operation was over.

Not quite. Marine air on Peleliu continued to attack the Japanese positions in Koror and Babelthuap. joining the patrolling Navy units in destroying or bottling up any remaining Japanese forces in the northern Palaus, A late casualty in that action was the indomitable Major Robert F. "Cowboy" Stout, whose VMF-114 had delivered so much effective air support to the ground combat on Peleliu. The stubborn determination of the Japanese to carry out their emperors war aims was starkly symbolized by the last 33 prisoners captured on Peleliu. In March 1947, a small Marine guard attached to a small naval garrison on the island encountered unmistakable signs of a Japanese military presence in a cave in the Umurbrogol. Patrolling and ambushes produced a straggler, a Japanese seaman who told of 33 remaining Japanese under the military command of Lieutenant Tadamichi Yamaguchi. Although the straggler reported some dissension within the ranks of that varied group, it seemed that a final banzai attack was under consideration. The Navy garrison commander moved all Navy personnel, and some 35 dependents, to a secure area and sent to Guam for reinforcements and a Japanese war crimes witness, Rear Admiral Michio Sumikawa. The admiral flew in and travelled by jeep along the roads near the suspected cave positions. Through a loudspeaker he recited the then-existing situation. No response. Finally, the Japanese seaman who had originally surrendered went back to the cave armed with letters from Japanese families and former officers from the Palaus, advising the hold-outs of the end of the war. On 21 April 1947, the holdouts formally surrendered. Lieutenant Yamaguchi led 26 soldiers to a position in front of 80 battle-dressed Marines. He bowed and handed his sword to the American naval commander on the scene.

|