|

"WE MARCHED AND FOUGHT THIS BATTLE WITHOUT BAGGAGE OR WAGONS"

The Army of the Potomac's Logisticians during the Gettysburg Campaign

Mark A. Snell

"Few appreciate the difficulties of supplying an

army. If you will calculate that every man eats, or is entitled to eat,

nearly two pounds a day, you can easily estimate what a large army

consumes. But besides what men eat, there are horses and mules for

artillery, cavalry, and transportation in vast numbers, all which must

be fed or the army is dissolved or made inefficient. There is another

all-important matter of ammunition, a large supply of which for infantry

and artillery must be carried, besides what is carried on the person and

in the ammunition chests of guns and caissons. Our men carry forty

rounds in boxes, and when approaching a possible engagement take twenty

more on the person. Of this latter, from perspiration, rain, and many

causes there is great necessary waste. It is an article that cannot be

dispensed with, of course, and the supply on the person must be kept up.

The guns cannot be kept loaded, therefore the diminution is constant

from this necessary waste. My division, at present numbers, will require

forty to fifty wagons to carry the extra infantry ammunition. You should

see the long train of wagons of the reserve artillery, passing as I

write, to feel what an item this single want is."

Alpheus Williams to his daughters

July 6, 1863

Nineteenth-century military theorist Baron Antoine

Henri Jomini defined logistics as "the practical art of moving

armies." He submitted that logistics also included "providing for

the successive arrival of convoys of supplies ... [and] establishing and

organizing ... lines of supplies." In other words, logistics was

defined as the "practical art of moving armies and keeping them

supplied." [1]

As important as logistical operations are to a

successful military campaign, there have been very few studies that

focus on this aspect of military history. Even in the field of Civil War

scholarship, where almost everything has been studied several times

over, little has been written. The few inquiries into this subject are

concerned with strategic logistics, or the movement of troops and

supplies within a given theater of war or between theaters. Only a

handful of Civil War studies focus on tactical logistics, which can be

defined as the movement and supply of troops in a given campaign or

battle. [2]

An examination of logistical operations during the

Gettysburg Campaign could fill an entire lengthy volume when one

considers the magnitude of moving and supplying the 163,000 soldiers who

comprised the two armies that participated. This essay, therefore,

merely will serve as a primer to familiarize students of the war with

the missions and staff functions of logisticians serving the field

armies, using the Army of the Potomac's logisticians as a case

study.

The three staff functions examined are the roles of

the Quartermaster General, the Commissary of Subsistence, and the Chief

Ordnance Officer.

Before jumping ahead to the summer of 1863, however,

it first is necessary to understand the historical background of the

United States Army's supply departments. When the Rebellion began in the

spring of 1861, the three army departments responsible for arming,

supplying, moving, and feeding U. S. soldiers found themselves in a

terrible predicament. Not only were the Quartermaster, Subsistence, and

Ordnance departments ill-prepared for a large-scale conflict, these

organizations also suffered the loss of many key officers who resigned

to join the Confederacy.

The Quartermaster Department, which was formed

in 1812, was responsible for land and water transportation, billeting,

clothing, providing some categories of personal equipment, and procuring

horses and forage. In 1861 the Department had an authorized strength of

37 officers and seven military storekeepers. Almost one-fourth of the

Department's officers, including the Quartermaster General, Brigadier

General Joseph E. Johnston, resigned to cast their lot with the South.

[3]

The Subsistence Department had similar

difficulties. Organized in 1818 and charged with feeding the troops, the

Department had an authorized strength of only twelve officers when the

war began. Secession brought the immediate resignation of four officers,

a loss of one-third of the Department. Congress remedied the situation

by passing legislation in August 1861 that added twelve more officer

positions, for a total of twenty-four. This was still too small an

officer corps to oversee the procurement and issue of food for hundreds

of thousands of men, so a year and a half later the department again was

modestly enlarged to twenty-nine officers. [4]

The Ordnance Department probably had the most

difficult assignment of the three supply departments in 1861: it was

responsible for the manufacture and procurement of small arms, edged

weapons, artillery, ammunition, and accouterments used by the land

forces. In addition, the Department was responsible for storage and

accountability of ordnance supplies at all Federal arsenals, for

maintaining those weapons once they were with the field armies, and for

issuing and transporting the ammunition.

Complicating matters was the fact that the United

States Government owned only two weapons manufacturing facilities when

the war began. The United States Armory at Harpers Ferry was captured

immediately by Confederate forces and its machinery dismantled and

transported south. This left the Springfield Armory as the lone

government-owned weapons-producing facility in the Union, thus making it

necessary for the Ordnance Department to contract with private gun

makers both at home and abroad. The end result was that many different

makes and calibers of small arms saw service in the Union army for the

first two years of the conflict. The Ordnance Corps originally had been

part of the Corps of Artillery, but in 1832 Congress passed legislation

to make it an autonomous department. Still, the Department had only

forty-one officers when the conflict began. [5] Some,

like Benjamin Huger, would resign to join the Confederate army, while

many other ordnance officers, such as Oliver Otis Howard and Jesse Reno,

would take field commands in the Union army.

Although the supply departments of the United States

Army were ill-prepared and undermanned before the outbreak of

hostilities, the men in charge of them would have to quickly overcome

any obstacles and adapt to the pressing needs of the service once the

shooting began. Most of the logistical officers of the Regular Army were

West Point graduates and had several years, if not decades, of

experience in their respective specialties. The rapid expansion of the

Union Army in 1861, however, would mean that untried and inexperienced

volunteers would fill the ranks of the Quartermaster, Ordnance, and

Subsistence departments for the war's duration.

By the time that the Army of Northern Virginia

embarked on its second invasion of the North, the logistical officers of

the Army of the Potomac had gained a wealth of experience since the

opening shots two years earlier. During the time since the first battle

of Bull Run, the officers and enlisted men of the three supply

departments had moved the entire Army of the Potomac to the Virginia

Peninsula and back again, they had armed the soldiers with adequate

small arms and artillery—albeit of many different types and

calibers—and they had supplied the troops by water, rail, and

overland transportation. (Rail transport was the responsibility of the

Director of Military Railroads, initially a civilian-run operation, but

the Quartermaster Department was responsible for all procurement

activities of that organization.) [6]

The Army of the Potomac's logisticians had learned

valuable lessons about locating forward supply depots too close to the

front lines, such as at Savage's Station, just east of Richmond. There,

on the Richmond and York River Railroad during the Seven Days' battles

the year before, hundreds of thousands of dollars in army supplies had

to be set to the torch lest they be captured by the advancing

Confederates. [7] During that same campaign, the

logisticians learned the hard way about the proper organization and

coordination of wagon train movements, for when Maj. Gen. George B.

McClellan ordered the change of his army's supply base from the York to

the James River, confusion reigned, and it was every wagon-train master

for himself. The result of the haphazard movement from the supply base

at White House on the York River, to Harrison's Landing on the James,

was the loss of almost half of the Army of the Potomac's 5000 wagons.

[8]

By the third summer of the war, the men responsible

for supplying, arming, and moving the Army of the Potomac had become

seasoned veterans. Army regulations had streamlined to some extent the

troops baggage trains, which now were organized, moved by schedule, and

left far to the rear when a battle was imminent. In addition, the

standardization of ammunition calibers finally was coming about, and the

soldiers were well-clothed and fed. The men in Washington charged with

overseeing these functions also had come a long way since 1861. The most

prominent was Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs. Meigs had not

been a quartermaster before the war, but had served his entire career in

the Corps of Engineers. For much of the previous decade he had been

assigned with the rank of captain as the chief engineer in charge of the

construction of the new Capitol dome in Washington. He was relieved from

this position in 1859 by the unscrupulous secretary of war, John B.

Floyd. Meigs was appointed Quartermaster General after Abraham Lincoln

took office. Meigs was a brilliant engineer and very detail-oriented.

His aggressive management of the Quartermaster Department's operations,

coupled with his strong belief in the Union cause, were the driving

factors behind his success. [9]

When the war began the head of the Subsistence

Department was Colonel George Gibson, an old man who had been an invalid

for many years. Running the day-to-day operations of the Department was

Lieutenant Colonel Joseph P. Taylor, who became the Commissary General

of Subsistence when Gibson died in September 1861. The Commissary

General's mission was as daunting as the tasks charged to Montgomery

Meigs. Unlike armies in European wars where the troops generally were

expected to live off the land, most food for the Union forces was

purchased in the major metropolitan areas of the North and then packed

and shipped to field depots. From there the foodstuffs were issued to

the commissary officers of the field armies and then transported to the

troops. The exception to this procedure was the procurement of flour and

beef, both commodities usually being purchased in the areas were the

armies were operating. Much of the fresh beef was transported with the

armies in herds and then slaughtered as needed. [10]

The Chief of Ordnance when the war began was another

old man, Colonel Henry Knox Craig, then seventy years of age. Deemed not

suitable to manage the wartime demands that would be placed on the

Department, he was replaced in April 1861 by Lieutenant Colonel James W.

Ripley, who at sixty-seven years of age was no young man himself. Yet

Ripley was equal to the assignment, and he certainly had the experience

to run the Department, having previously served in several important

ordnance positions including stints as commander of Watertown Arsenal

and Springfield Armory. His most important duty would be to properly arm

the hundreds of thousands of men entering the Union army. Although the

Ordnance Department has been greatly criticized by some historians for

failing to arm the troops with the most modern weapons then available, a

close examination of the facts reveals that Ripley and his officers

accomplished a monumental task just ensuring that most of the front line

troops were armed with rifled-muskets, regardless of their make,

caliber, or from which end of the barrel they were loaded. By 1863,

domestic production of first-quality rifled-muskets had made it possible

to begin replacement of all but the best European-made arms, such as the

Enfield, then in the hands of the troops. [11]

Still, the Army of the Potomac's soldiers carried a

variety of different long arms onto the field of battle at Gettysburg,

including .54, .577, .58, and .69 caliber muskets, and a few units

carried breech-loading Sharps rifles. (The .577 and .58 caliber were

interchangeable, and most of the .69 caliber weapons were smoothbores.)

Cavalry troopers were armed primarily with .52 caliber Sharps carbines,

although a few other makes and calibers could be found. Troopers also

were armed with .44 or .36 caliber single-action pistols. Union

artillery primarily employed "twelve-pounder" smooth-bore cannon that

fired spherical ammunition, and "ten-pounder" Parrott rifles and

three-inch ordnance rifles that fired elongated concoidal ammunition.

Only one Union battery in the Army of the Potomac employed a larger

cannon, the twenty-pound Parrott rifle. [12]

It is important to recognize that the greater the

variety of ammunition required, the more wagons were required to haul it

(only one type of ammunition was authorized per wagon), and the greater

the chance that the wrong caliber of ammunition would be issued during

the heat of battle.

All three supply departments had experienced problems

with crooked contractors early in the war, part of which was exacerbated

by a lack of qualified officers who could check the corruption and

fraud. Legislation expanding the departments remedied the situation

somewhat, but the small number of Regular Army officers filling critical

positions would hamper the efficiency of the logistical departments for

the rest of the war. Since ordnance, quartermaster, and subsistence

officers also were authorized on army, corps, division, and sometimes

brigade and regimental staffs, there obviously would not be enough

qualified officers to go around. Thus, these staff positions usually

were filled by line officers, who normally were volunteers themselves.

When officers were placed in logistical staff positions but were not

assigned to the respective supply departments, they were designated as

"acting-," such as "acting assistant quartermaster" or "acting

commissary of subsistence." The majority of the logistical officers in

the Army of the Potomac fit this bill.

In the summer of 1863, however, the three chief

logisticians of the Army of the Potomac were Regular Army officers

holding commissions in their respective departments, and they all had a

good deal of field experience in their areas of expertise.

Key among the Army of the Potomac's logisticians was

its quartermaster general, Brigadier General Rufus Ingalls, an 1843

graduate of West Point and a classmate of U. S. Grant. A Maine native,

Ingalls originally was commissioned a dragoon officer and saw service

during the Mexican War. He became a quartermaster in 1848, so by the

time of the Civil War he had thirteen years' experience under his belt.

[13] Ingalls became the Quartermaster General of the

Army of the Potomac at the close of the Peninsula Campaign in the summer

of 1862. He was a little more than a month away from his 44th birthday

when the Battle of Gettysburg was fought. [14]

The Chief Commissary of Subsistence was Colonel Henry

F. Clarke of Pennsylvania. Like Ingalls, Clarke also was a 1843 graduate

of West Point. He finished 12th in the class of 1843, ahead of both

Ingalls and U. S. Grant. His friends gave him the nickname "Ruddy,"

apparently because of his rugged complexion. He was commissioned in the

artillery and served in the 2nd U. S. Artillery in Mexico where he was

wounded in action and breveted for gallantry. [15]

After the Mexican War, he was assigned as a mathematics professor at

West Point where he formed close friendships with future Union generals

George McClellan, William Franklin, and Fitz John Porter, as well as

future Confederate General Dabney Maury. [16] Clarke

transferred from the artillery to the Subsistence Department in 1857 and

served as the Chief Commissary of Subsistence for the Mormon Expedition

that same year. In 1861, he married the daughter of Joseph Taylor, the

Commissary General of Subsistence of the U. S. Army. Clarke became the

Chief Commissary of Subsistence for the Army of the Potomac when his

friend McClellan took command in the summer of 1861. [17] Ruddy Clarke was forty-two years of age in the summer

of 1863.

Captain Daniel Webster Flagler was the Army of the

Potomac's Chief Ordnance Officer. A native of New York State, he

graduated from the United States Military Academy in June 1861 and was

commissioned directly into the Ordnance Corps. He served as an acting

aide-de-camp to Colonel David Hunter at the first battle of Bull Run and

subsequently became an aide to Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell from the end of

July until December 1861. During Ambrose Burnside's expedition to the

North Carolina coast Flagler was assigned as the chief ordnance officer

for the entire expedition. When Burnside's command joined the Army of

the Potomac in the late summer of 1862, he served as an assistant

ordnance officer and aide-de-camp on Maj. Gen. Burnside's staff. Flagler

became the Army of the Potomac's chief ordnance officer on November 21,

1862 when Burnside was elevated to its command. [18]

At age twenty-eight, Captain Flagler was the youngest of that army's

three supply chiefs.

Ingalls, Clarke, and Flagler were the primary staff

officers of their respective logistical functions in the Army of the

Potomac, but they could not possibly supply and move the army by

themselves. The staff officers in the echelons below army

level—normally "acting commissaries," "acting quartermasters," and

"acting ordnance officers"—consolidated requests from their

subordinate units, ensured the paperwork was filled out properly, and

forwarded the requests to the next higher command. When the requests

were filled, these men ensured that the correct number and type of

supplies were picked up, transported, and issued to their subordinate

commands. For example, the chief commissary of subsistence for the First

Division of V Corps would have provided staff supervision for the

requisitioning, transportation, and issue of food for the three brigades

assigned to his division. The brigade chief commissaries had similar

responsibilities and provided staff supervision of the regimental

quartermasters (commissary officers were not authorized in regiments).

This setup was similar for the chief quartermasters, but ordnance

officers were not authorized any lower than division level staffs.

Since the regiment was the basic building block of

the army's organizations, most of the hands-on logistical work occurred

at the regimental level. In the majority of instances, the lieutenants

serving in these logistical functions were line officers of their

respective branches (ie.; cavalry, infantry, or artillery) At the

regimental level of organization, the quartermaster also served as the

commissary officer, but he was assisted by a quartermaster sergeant and

a commissary sergeant. Ordnance officers were not authorized at the

brigade and regimental level, but most regiments were authorized an

ordnance sergeant who issued ammunition and made minor repairs on his

unit's weapons. Still, many brigade and regimental commanders chose to

have an officer oversee their units' ordnance supply and transportation,

so they appointed a line officer to this position as an extra duty. At

the company level of organization, infantry units were authorized a

wagoner, and cavalry companies were authorized two farriers, one

saddler, one quartermaster sergeant, one commissary sergeant, and two

teamsters. Artillery batteries were authorized a quartermaster sergeant,

two to six artificers (repairmen), and a wagoner. [19]

During the Chancellorsville campaign in the spring of

1863, the main supply base of the Army of the Potomac was at Aquia

Creek, a tributary of the Potomac River about 25 miles southwest of

Washington. On June 14 the depot there was ordered abandoned, but

Quartermaster General Meigs was adamant that as much government property

as possible should be saved. During the next three days, over 10,000

wounded and sick soldiers were moved, as was 500 car loads of army and

railroad property. With its base of supply closed down, the Army of the

Potomac marched westward to the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, which

became its main line of supply. [20]

Once it had been determined that Robert E. Lee's

intention was to strike across the Potomac River into Maryland and

Pennsylvania, General Ingalls decided to make Baltimore the Army of the

Potomac's main supply base. [21] While the Union force

groped northward in search of Lee's army, Ingalls, Clarke, and Flagler

saw to it that the vast supplies of the army were stockpiled at

strategic locations and several days supply of food, ammunition, forage,

and other essentials accompanied the troops. To do this, long wagon

trains followed in the rear of the forces or traveled on alternate

roads. As the supplies were consumed, empty wagons were sent back to the

forward supply depots for replenishment and returned with full loads.

Ingalls later reported that "our transportation was perfect, and our

source of supply same as in...[the Maryland] campaign. The officers in

our department were thoroughly trained in their duties. It was almost as

easy to maneuver the trains as the troops." [22]

The forward depots of the Army of the Potomac during

the Gettysburg Campaign were adjacent to rail stations, since the

railroad was the main means of transportation for the bulk supplies.

Once the cargo had been off-loaded from the cars by enlisted men and

civilian laborers, supply officers would set up storage areas with the

different supplies organized by type or category. A careful inventory

was maintained by the supply officers so that they would know how many

days of supply, by item, that they had on hand. Issues were made from

these stocks to the supply officers assigned to the various corps of the

Army. As supplies began to dwindle, telegrams were sent to the

respective supply bureaus in Washington where orders were issued to

release stocks from the main depots, such as Washington Arsenal.

Complicating matters was the fact that the Army of

Northern Virginia destroyed railroad bridges, rolling stock, and

sections of track as it moved through enemy territory. To the rescue

came Herman Haupt, a brilliant engineer who always seemed at his best

during crisis situations. A native of Pennsylvania, Haupt graduated from

West Point in 1835 along with George Meade, who had taken over command

of the Army of the Potomac on June 28, 1863. Haupt resigned his

commission shortly after graduation from the academy and went to work

for the railroads. He taught for a while at Pennsylvania College in

Gettysburg, and in 1851 published a book titled The General Theory of

Bridge Construction, which was considered a significant contribution

to the engineering profession at the time. Haupt had several other

important positions during the antebellum period, including general

superintendent and later chief engineer of the Pennsylvania Railroad,

and chief engineer in charge of construction of the Hoosac Tunnel in

Massachusetts. He had served the War Department since the spring of

1862, and his accomplishments under very adverse conditions had enabled

him to acquire almost dictatorial authority over the military operations

of the railroads in the Eastern Theater. One historian of Civil War

railroads has said that Haupt took pleasure in surmounting difficulties,

and was delighted to find a badly tangled situation which he could clear

up with his magic touch. ...this humorless man was responsible for

developing not only the general principles of railroad supply operation,

but also detailed methods of construction and destruction of railroad

equipment. To this capable engineer and brilliant organizer is due most

of the credit for the successful supply of the Army of the

Potomac.... [23]

Haupt took control of the situation on June 27 when,

in Special Orders No. 286, General-in-Chief Henry Halleck authorized and

directed him "to do whatever he may deem expedient to facilitate the

transportation of troops and supplies to aid the armies in the field in

Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania." [24]

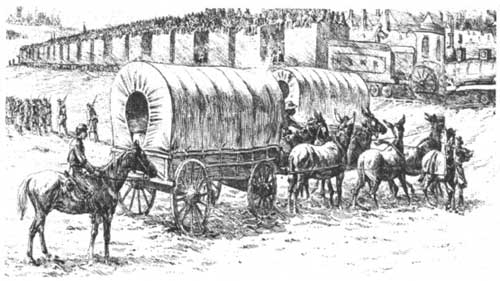

Even if Haupt could repair the tracks and keep the

trains moving, it took wagons, mules, horses, and teamsters to transport

the supplies from the forward depots to the army, and the Army of the

Potomac had an abundance of wagons during the Gettysburg

Campaign—3,652, not counting ambulances. Four horses or mules were

required to pull an army wagon, sometimes six animals if the wagon was

overloaded, so a minimum of 14,608 animals were required just to

move the supplies and baggage of the Army of the Potomac. [25] Transportation and supply reforms earlier in the year

were supposed to decrease the number of wagons accompanying the army on

campaign. General Ingalls estimated that "one wagon to every 50 men

ought to carry 7 days' subsistence, forage, ammunition, baggage,

hospital stores and everything else." This was a standard of twenty

wagons to every thousand men. During the Gettysburg Campaign, there was

one wagon for every 25.6 men, which translates to roughly 39 wagons per

1,000 men. If the transportation reforms had been adhered to, the Army

of the Potomac would have required only 1,870 wagons, 1,782 less than

what was actually employed. [26]

The total number of horses and mules employed by the

Army of the Potomac at the Battle of Gettysburg has been estimated at

43,303. Ingalls not only was accountable for the horses used by his own

trains, he also was responsible for the replacement of horseflesh for

the artillery and cavalry as well. [27] For example,

General Alfred Pleasanton's Cavalry Corps had been very active the month

of June, and the wear and tear on the horses was beginning to tell.

Ingalls telegraphed Pleasonton on June 26 to inform him that 700 horses

were being shod at Alexandria and were ready for issue. [28]

The supply of forage for the horses and mules was

Ingalls' responsibility, too. In the same telegram that he sent

Pleasanton on the June 26, Ingalls asked him if "fifty wagons, laden

with forage" had yet reported to his command. [29]

Since these animals normally required twelve pounds of grain and

fourteen pounds of hay per day, almost 520,000 pounds of feed and

606,000 pounds of hay had to be supplied to the Army of the Potomac

every day of the campaign if the horses were going to remain healthy.

Grazing would reduce the amount of feed and forage required to keep the

horses fit, but the great number of Union and Confederate horses (over

72,000 combined) quickly devoured the grasses and other edible

vegetation in the Gettysburg area. Comments by the soldiers of the

cavalry and artillery about their worn-out horses indicate that the poor

brutes were not eating very well, and it is no wonder that forage

probably constituted the largest single commodity of supply during the

Battle of Gettysburg. [30]

Those men not lucky enough to ride a horse had to

walk, and the wet weather and macadamized roads of Maryland and

Pennsylvania were taking their toll on the footwear of the Union

soldiers. On June 28 Ingalls wired Meigs that at least 10,000 pairs of

shoes and socks were needed at Frederick to issue to soldiers as the

various corps of the Army of the Potomac passed through the town.

Ingalls telegraphed back the same day that the "bootees and socks

have been ordered, and will be sent as soon as a safe route and escort

can be found." Then Meigs followed with a terse message:

Last fall I gave orders to prevent the sending of

wagon trains from this place to Frederick without escort. The situation

repeats itself, and gross carelessness and inattention to military rule

has this morning cost us 150 wagons and 900 mules, captured by cavalry

between this and Rockville.

Yesterday morning a detachment of over 400 cavalry

moved from this place to join the army. This morning 150 wagon were sent

without escort. Had the cavalry been delayed or the wagons hastened,

they could have been protected and saved.

All the cavalry of the Defenses of Washington was

swept off by the army, and we are now insulted by burning wagons 3 miles

outside of Tennallytown.

Meigs ended his missive with the sarcastic conclusion

that "[y]our communications are now in the hands of General Fitzhugh

Lee's brigade." [31]

The wagon train in question had been captured by the

troopers of J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry as it was making its circuitous ride

around the Army of the Potomac. Ingalls shot a telegram back, stating

that it was unfortunate that the train was captured, but he did not even

know about the Union cavalry force leaving earlier in the day, nor did

he feel any ordinary guard force could have prevented the train's

capture. [32] Shortly after sending this message,

Ingalls received another telegram, this one from his assistant, Lieut.

Col. Charles G. Sawtelle, who said he had just seen Gen. Meigs, who in

turn told him there was to be an investigation concerning the loss of

the wagon train. [33]

Now Ingalls was very upset. He telegraphed Meigs that

he did not understand how the Quartermaster General could hold

him responsible, since he had nothing to do with the escort. [34] Meigs apparently settled down and became more

rational. In a follow-up message to Ingalls he mentions that 25 teams of

mules sent later in the day to Edwards Ferry, Maryland, also had been

captured, yet Meigs did not lay fault this time. In fact, he told

Ingalls that he was sending 20,000 pairs of shoes and socks instead of

the 10,000 pairs ordered, and that 600,000 pounds of grain had been

loaded on a train, ready for him if he needed it. [35]

Ingalls obviously had better things to do than engage

in a war of words with the Quartermaster General. The Army of Northern

Virginia was somewhere in Pennsylvania, and the Union army was

desperately trying to ascertain its whereabouts. To prevent the clogging

of roads by the Army of the Potomac's supply trains as the forces

approached Gettysburg, Ingalls made sure that the combat units always

had the right-of-way. He later wrote that "[o]n this campaign, ...our

trains, large as they were necessarily, never delayed the march of a

column, and, excepting small ammunition trains, were never seen by our

troops. The main trains were conducted on roads to our rear and left

without the loss of a wagon." [36]

Once the battle was opened on July 1, Westminster,

Maryland, was selected as the forward supply base of the Army of the

Potomac. In his official report written months after the battle, Ingalls

described the logistical scenario as the battle unfolded:

The wagon trains and all impedimenta had been

assembled at Westminster, on the pike and railroad leading from

Baltimore, at a distance of about 25 miles in the rear of the army. No

baggage was allowed in front. Officers and men went forward without

tents and with only a short supply of food. A portion only of the

ammunition wagons and ambulances was brought up to the immediate rear of

our lines. This arrangement, which is always made in this army on the

eve of battle and marches in the presence of the enemy, enables

experienced officers to supply their commands without risking the loss

of trains or obstructing roads over which the columns march. Empty

wagons can be sent to the rear, and loaded ones, or pack trains, brought

up during the night, or at such times and places as will not interfere

with the movement of troops. [37]

General Ingalls was not the only supply chief who was

busy on the eve of the battle. From his tent at Headquarters, Army of

the Potomac, then located in Taneytown, Maryland, Col. Ruddy Clarke

scribbled a hurried report at 10 p.m., June 30, to his father-in-law,

Commissary General Joseph Taylor. He informed General Taylor that the

army had seven days' rations on hand except for the cavalry, which

apparently had out-distanced its supply wagons. (On June 30, Brig. Gen.

John Buford, commanding the 1st Division, Cavalry Corps, telegraphed to

his wing commander, Maj. Gen. John Reynolds, "I can get no forage or

rations; am out of both. The people give and sell the men something to

eat, but I can't stand that way of subsisting; it causes dreadful

struggling."

Clarke forecasted his subsistence requirements and

requested that 300,000 rations of hard bread, coffee, and sugar, 100,000

rations of pork or bacon; 100,000 rations of candles; 150,000 rations of

salt; and 50,000 rations of soap be loaded on rail cars in Washington or

Baltimore and kept ready to be sent forward. Clarke stipulated that if

hard bread could not be supplied, then flour must be substituted. He

also demanded that the coffee was to be roasted and ground. Colonel

Clarke then told his chief that one of his assistants had been sent to

the main supply base at Baltimore to arrange matters for the Army's

future food supply, but that he had not yet arrived, the Army of

Northern Virginia having destroyed a section of the Baltimore and Ohio

Railroad on which his assistant was traveling. After informing the

Commissary General that the Army of the Potomac "was well off for

beef cattle," which were following in herds behind the supply

trains, Clarke concluded that, "it is necessary I should be kept

informed of the arrangement made by the [Subsistence] Dept. to supply

this army in so far as I have requested and otherwise." [38] But the situation rapidly changed. Two and a half

hours later, at 12:30 a.m. on July 1, Clarke sent an urgent telegram to

Taylor which read, "...send three hundred thousand (300,000) marching

rations to Union Bridge on the Westminster Rail Road as soon as

possible." [39]

Captain Daniel Flagler, the Chief Ordnance Officer of

the Army of the Potomac, apparently sent few messages back to Washington

during this time period. Since the infantry and artillery had not been

engaged for several weeks, enough ammunition was on hand for any

imminent confrontation with the enemy. The cavalry had been in contact

with the enemy several times in June, but the status of their ammunition

supply on the eve of the Battle of Gettysburg is not known. (The

troopers apparently had enough ammunition, since none of the cavalry

brigade or division commanders mentioned any shortages in their messages

or reports.) General Orders No. 20, Headquarters Army of the Potomac,

dated March 25, 1863, dictated that infantry divisions must constantly

have on hand 140 rounds per man, and cavalry must have 100 rounds

carbine and 40 rounds pistol ammunition per man. Both of these figures

included the rounds soldiers carried in their cartridge boxes. For the

artillery, 250 rounds per gun were required to be on hand, including

that carried in the limber's ammunition chest.

These same general orders dictated that the wagons

carrying a division's reserve ammunition would be marked by a six-inch

wide horizontal stripe painted on the canvas. Artillery ammunition had a

red stripe, cavalry a yellow stripe, and infantry had light blue. To

prevent confusion in a combat situation, the wagons had to be

"distinctly marked with the number of the corps and division" to

which they belonged, as well as the type and caliber of the ammunition

they carried. [40] Captain Flagler apparently was so

unmoved by the events transpiring on July 1 that he took the time that

day to fulfill one of the Ordnance Department's bureaucratic

requirements: he sent to the Chief of Ordnance in Washington the Army of

the Potomac's quarterly "disbursement" and "accounts current" reports

for the second quarter of calender year 1863. [41]

By July 2, the flow of supplies was coming into

Westminster without much difficulty. The major supply artery between

Baltimore and Westminster was the Western Maryland Railroad. It had only

a poorly constructed single track, no telegraph line, and no adequate

sidings. Its main station was at Westminster, and the terminus was at

Union Bridge. Herman Haupt was at Westminster on July 1. He immediately

brought order to a very confusing situation, since the line was being

operated off schedule to prevent capture of the trains. After assessing

the situation, Haupt sent for construction supplies, tools, lanterns,

and 400 laborers. He also borrowed rolling stock from several other

railroads. Since there was only one track and no acceptable sidings,

Haupt sent the trains to and from Westminster three convoys a day, five

or six trains at a time, with ten cars per train. Haupt calculated that

by keeping to this plan, he could move 1,500 tons of supplies a day from

Baltimore, and return with 2,000 to 4,000 wounded soldiers. Two other

rail lines also were available for use at this time, the North Central

from Baltimore to Hanover Junction, and the B & O to Frederick. [42] Most supplies went over the Western Maryland,

however, since the route through Westminster was the most direct path to

Gettysburg.

Meanwhile, General Ingalls moved with army

headquarters and directed resupply operations from Gettysburg. He made

arrangements to issue supplies at Westminster and eventually at

Frederick, and ensured that telegraphic communications were open between

these two towns and Baltimore and Washington. He then established

communications with Westminster and Frederick by sending relays of

cavalry couriers every three hours. [43]

At 7 a.m. on July 3, Ingalls wired Meigs that

"[a]t this moment the battle is raging as fiercely as ever.... We

have supplies at Westminster that must come up to-morrow if we remain

here." He concluded by correctly predicting that "[t]he contest

will be decided today, I think." [44] Only

ammunition wagons and ambulances had been allowed to accompany the

various Union corps to Gettysburg, and after three days of fighting,

Ingalls knew that the Army of the Potomac soon would have to be

resupplied. His efforts had made the situation appear to be almost

routine, but on July 3 he had a close call. While Ingalls was conversing

with Generals Meade and Butterfield during the artillery duel that

preceded Pickett's Charge, a shell from a Confederate gun exploded so

close to the trio that it knocked down and severely wounded Butterfield,

but neither Ingalls nor Meade was hurt. [45] (During

the same bombardment the ordnance officer responsible for the ammunition

of the Army of the Potomac's Artillery Reserve reported that

"[s]everal shells passed over the [ammunition] train, and three or

four fell among the teams, only one exploding. A mule in one of the

teams was stuck by a solid shot and killed, and many of the animals

became so unmanageable that there was danger of a stampede.") [46]

Back in Westminster, the rations that Colonel Clarke

had requested in the early morning hours of July 1 finally began to

arrive on July 2. Private James Terry, a teamster assigned to Company A,

7th Wisconsin Infantry, noted in his diary that "100 teams came from

Washington with rations for the troops. We are 25 miles from them [the

troops at Gettysburg]." [47] Late the next day,

July 3, orders were received in the Army's wagon parks in Westminster to

proceed to Gettysburg with fresh rations. The magnitude of this task was

daunting; in the Third Corps alone, which had only two divisions, 60,000

rations and 250 head of cattle were sent northward on the Baltimore Pike

towards Gettysburg. [48] Hundreds of wagons headed

northward on the Baltimore Pike and off-loaded their supplies, most of

which began arriving during the early morning hours of July 4. A First

Corps soldier who had been captured on July 1 and had escaped the

morning of July 4 remembered that he had just gotten back to the Union

lines in the morning when the commissary wagons began arriving. "[W]e

soon filled our haversacks with coffee, sugar, pork, and hardtack, the

standard articles of a soldiers diet," he wrote. [49]

In Washington, Quartermaster General Meigs prepared

for the battle's aftermath. He sent messages to quartermasters in

Philadelphia and Harrisburg directing them to purchase as many wagons

and horses as possible to replace expected losses in the Army of the

Potomac. On July 4 Meigs telegraphed Ingalls to buy or impress all the

serviceable horses that were within the rage of his foraging parties.

Priority for fresh mounts went to the combat arms: he directed Ingalls

to "refit the cavalry and artillery in the best possible manner."

Instructions also were sent to the quartermaster at Baltimore to

redirect all remounts to Frederick as replacements for the cavalry. As

if to underscore his priorities, Meigs sent a message to Herman Haupt at

Westminster: "Let nothing interfere with the supply of rations for

the men, and grain for the horses..." On July 6, General Meigs

telegraphed his counterpart in the Army of the Potomac that 5,000 horses

would be headed by rail for Frederick from depots across the East and

Midwest. [50]

The soldiers of the Army of the Potomac and their

horses needed sustenance, but they required ordnance supplies, too. One

historian has estimated that the Union soldiers probably expended over

5,400,000 rounds of small arms ammunition during the three days of

fighting. [51] Captain Flagler estimated that at least

25,000 artillery rounds also had been fired or lost as well. [52] (He was not far off the mark: Brig. Gen. Henry Hunt,

Chief of Artillery, later reported that 32,781 rounds were fired or lost

during the battle.) [53] The situation was serious

enough that General Meade issued a circular on July 5 urging his corps

commanders to be cautious in expending both their small arms and

artillery ammunition. "We are now drawing upon our reserve

trains," the circular stated, "and it is of the highest

importance that no ammunition be exhausted unless there is reason to

believe that its use will produce a decided effect upon the enemy."

[54]

On July 6, Captain Flagler wired General Ripley at

the Ordnance Bureau. After informing his chief that a wagon train of

ammunition was standing by at Frederick, he requested the following

ordnance supplies be sent to Gettysburg:

- 800,000 cartridges, caliber .574

- 100,000 .69-caliber rifled-musket cartridges

- 200,000 .54-caliber cartridges

- 200,000 .69-caliber smooth-bore cartridges

- 30,000 Sharps rifle cartridges

For the artillery, he initially requested

- 2500 12-pound rounds

- 2,500 rounds for 3-inch rifles

- 1,500 rounds for ten pounders. [55]

Shortly after his request was sent, Flagler found out

that the Army of Northern Virginia had begun its withdraw. Since the

Army of the Potomac soon would be in pursuit, Flagler requested that the

ammunition be sent to Frederick instead of Gettysburg. He also asked if

his earlier request for artillery ammunition could be increased to 4,000

rounds each of 3-inch and 12-pound rounds. The telegraph operator made a

mistake, however, and requested 40,000 rounds each. Upon arriving in

Frederick, Flagler discovered the error, took what he needed from the

supply train—15,000 rounds each of 3-inch and 12-pound ammunition,

much more than his earlier request—and sent the rest back to the

Washington Arsenal. [56] Although he drew enough

artillery ammunition to compensate for that which had been expended, the

amount of small arms ammunition that Flagler requested appears to be

much too low.

Some ordnance officers remained in Gettysburg when

the Army of Potomac marched southward after Lee's army. Over 24,000

muskets were collected by the Ordnance Department in the immediate

aftermath of the battle, as well as thousands of bayonets, cartridge

boxes, and other accouterments. [57] Some of these

items would be reissued to the troops, while many were sent back to

Washington Arsenal for repair. Similarly, General Meigs sent Captain

Henry C. Blood of the Quartermaster Department from Washington on July 6

to assist with the collection of government property and oversee the

burial of the dead. The first week he was in Gettysburg his time was

occupied with getting the dead buried. Thousands of horses on both sides

had been killed, and their carcasses also had to be disposed of. After a

quick return to Washington, Blood was back in Gettysburg by July 16 and

spent much of his time supervising the collection of equipment from the

battlefield and the confiscation of U. S. property from the citizens of

Gettysburg who had picked it up on the field. Wounded and worn-out

horses which were wandering aimlessly about the battlefield or had been

taken by civilians also were rounded up. In fact, Meigs received word

from Gettysburg on July 18 that over 350 horses and mules had been

recovered and, with proper care and medication, could be made ready for

service in a very short time. The recovery of equipment at Gettysburg by

the Quartermaster Department would continue through the end of August.

[58]

As the Army of the Potomac moved farther away from

the Gettysburg area in its pursuit of General Lee, the supply trains

that had been assembled at Westminster were ordered to rejoin their

respective corps by way of Frederick so they could re-stock from the

forward depot established there. [59] The badly

wounded had no choice but to remain in Gettysburg, and arrangements had

to be made for their care. Colonel Clarke ordered 30,000 rations brought

to Gettysburg on July 4 to be issued specifically to the hospitals, and

he ordered more to be delivered after the army departed. [60] When the Army moved west from Frederick, once again

only ammunition and ambulance trains were allowed to accompany their

commands. Supply and baggage wagons were to remain in the Middletown

Valley on the evening of July 9. The trains were left without guards.

The severe manpower losses sustained by the Army of the Potomac at

Gettysburg required every able-bodied man to be in the ranks. While

Meade's command was taking up positions around Williamsport from 10 - 13

July to attack the Confederate army, the trains remained in Middletown

Valley and supplied the Army from there. [61]

After the Army of Northern Virginia escaped across

the Potomac, General Ingalls ordered his logisticians to replenish the

Army's supplies from depots that had recently been established at Berlin

and Sandy Hook, Maryland, and Harpers Ferry, West Virginia. Three days'

worth of cooked rations were issued to the troops, and those men who

needed replacement articles of uniform were issued them at that time. In

addition, fresh horses and mules were issued to commands that required

them, though probably not in the requisite numbers, as it would take

some time for the horses that Meigs ordered sent to the Army to actually

arrive. Once the Army crossed the Potomac, Ingalls made the necessary

arrangements to resupply the command via the Orange and Alexandria

Railroad. [62] Thus ended the Gettysburg Campaign from

the logistical perspective.

The logisticians of the Army of the Potomac had

accomplished a herculean task, but the soldiers and animals were worn

out. Muddy roads from heavy rains made resupply difficult as the Union

force pursued Meade through Maryland, making tired men and horses even

more exhausted. The campaign had taxed the transportation assets of the

army to its fullest, and food and forage was running low. [63] Ammunition supplies had been replenished, but it is

doubtful that the Army of the Potomac had as much ordnance on had as it

did when the battle began, especially in light of the modest

requisitions made earlier by Flagler—almost 3,000,000 small arms

rounds less than what was expended.

The major logistical lesson that was learned from the

Gettysburg Campaign was that large supply trains degrade the tactical

mobility of an army. In order to reduce the number of wagons

accompanying the Army of the Potomac on campaign, General-in-Chief Henry

Halleck issued a general order on August 21, 1863 that instituted, for

the entire United States Army, the transportation recommendations made

earlier by General Ingalls: no more than twenty wagons would be allowed

per every 1,000 men. [64] (Field commanders, however,

would not always abide by this policy.)

Even though Ingalls had done a magnificent job in

resupplying the Army while at the same time keeping the ponderous wagon

trains out of harm's way—and out of the way of the combat elements

of the Army—the logistical umbilical cord had been stretched thin.

The horrific three-day battle was the largest and most intense that had

ever been fought on American soil, and the supply of military

necessities could not keep up with the demand, especially ammunition.

From a purely tactical point of view, Meade should have counterattacked

Lee on the 4th or 5th of July. When the element of logistics is factored

into the equation, Meade probably made the correct decision not to

attack.

And what happened to the men who orchestrated the

supply efforts of the Army of the Potomac during the Gettysburg

Campaign? Ruddy Clarke remained the Chief Commissary of Subsistence of

the Army of the Potomac until the spring of 1864. At his own request he

was transferred to a commissary post in New York. Clarke was breveted to

major general on March 13, 1865 for faithful and meritorious service

during the war. When the conflict ended, he stayed in the army and

served in several commissary positions, including Chief Commissary under

General Sheridan in the Division of Missouri. Henry Francis Clarke died

on May 10, 1887. [65]

Daniel Flagler became ill shortly after the battle

and took sick leave from the army. Once he had recovered, he was

reassigned to inspection duty at the West Point Foundry from October

1863 until May 1864, and finished the war as an assistant in the offices

of the Ordnance Bureau in Washington, D. C. He was breveted to

Lieutenant Colonel in March 1865 for distinguished service in the field

and faithful service to the Ordnance Department. After the war, Flagler

had a number of different ordnance assignments, his most notable as

commander of Rock Island Arsenal, Illinois, for 15 years. He was

promoted to brigadier general in the Regular Army and appointed the

Chief of Ordnance in January 1891. He still served in this capacity

during the Spanish American War. General Flagler died on March 29, 1899.

[66]

Rufus Ingalls remained the Army of the Potomac's

quartermaster general for the duration of the war. At the end of the

conflict he was breveted to major general for faithful and meritorious

service during the war. Like his two other fellow logisticians, he, too,

stayed in the regular army, and was promoted to increasing positions of

responsibility, becoming Quartermaster General of the United States Army

in February 1882. Ingalls retired on July 1, 1883, twenty years to the

day after the Battle of Gettysburg began. He died ten years later, on

Jan. 15, 1893. [67]

The men who moved, armed, fed, and supplied the Army

of the Potomac are a shining example of American logisticians at their

best. Although no monuments were dedicated at Gettysburg to honor their

memory, it is obvious that their efforts were critical to the success of

the Army of the Potomac during the first week of July 1863. If nothing

else, these men certainly deserve more attention by historians than they

have received in the past.

NOTES

1. Cited in Martin Van Creveld,

Supplying War: Logistics from Wallenstein to Patton (Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1977), p. 1.

2. A discussion of theater-level

logistics can be found in Herman Hattaway and Archer Jones, How the

North Won: A Military History of the Civil War (Urbana: University

of Illinois Press, 1983); Edward Hagerman, The American Civil War and

the Evolution of Modern Warfare (Bloomington: Indiana University

Press, 1988); and several studies on Civil War railroads. (Hagerman

discusses logistics—and the impact on tactical doctrine—during

the Gettysburg Campaign in moderate detail, but mostly from the

perspective of Rufus Ingalls, Quartermaster General of the Army of the

Potomac.) The role of Northern and Southern industry in manufacturing

weapons and supplies, as well as the role of agriculture in feeding the

armies has received scholarly attention, but not nearly the

consideration it deserves. In The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in

Command, Edwin Coddington devotes a chapter to the discussion of

arms, equipment, and organization of the two armies, but his

concentration was not a detailed analysis of logistical operations. See

the chapter "Arms and Men" in The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in

Command (New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1968), pp. 242-259. The

best overall treatment of military logistics is Martin Van Creveld's

Supplying War but, unfortunately, the author focused on European

wars and failed to even mention the impact of the American Civil War on

the evolution of military logistics. The one study of tactical logistics

during the Civil War is William J. Miller's "'Scarcely any Parallel in

History': Logistics, Friction, and McClellan's Strategy for the

Peninsula Campaign" in William J. Miller, ed., The Peninsula Campaign

of 1862: Yorktown to the Seven Days, vol. 2 (Campbell, CA: Savas

Woodbury Publishers, 1995). A brief, yet well written discussion of

Civil War field logistics can be found in Jay Luvass and Harold Nelson,

editors, The U. S. Army War College Guide to the Battle of Antietam:

The Maryland Campaign of 1862 (Carlisle, PA: South Mountain

Publishers, 1987). See Appendix I, "Field Logistics in the Civil War,"

(pp. 255-284), by Lieutenant Colonel Charles R. Shrader.

3. Erna Risch, Quartermaster

Support of the Army: A History of the Corps, 1775-1939 (Washington:

Center of Military History, U. S. Army, 1989 [2nd edition]), pp. 136,

334.

4. Ibid., pp. 202, 382-83.

5. Carl L. Davis, Arming the

Union: Small Arms in the Civil War (Port Washington, NY: National

University Publications, 1973), p. 14.

6. Risch, Quartermaster

Support, p. 397.

7. Stephen W. Sears, To the Gates

of Richmond: The Peninsula Campaign (New York: Ticknor & Fields,

1992), p. 263.

8. Hagerman, The American Civil

War and the Origins of Modern Warfare, p. 51.

9. Meigs' life is chronicled in

Russell B. Weigley's Quartermaster General of the Union Army: A

Biography of Montgomery C Meigs (New York: Columbia University

Press, 1959).

10. Ibid., pp. 382-385. For a

discussion of European methods of subsisting the troops during the

period from the early Napoleonic campaigns through 1866, see Van

Creveld, Supplying War, pp. 40-82.

11. Davis, Arming the Union,

pp. 12-14, 76. Davis provides a revisionist interpretation of the role

of the Ordnance Department. He convincingly argues that the officers of

the Ordnance Department were extraordinary in their untiring efforts to

place first-rate rifled arms in the hands of the troops.

12. For a listing of small-arms

calibers and types, by unit, see Dean Thomas, Ready, Aim, Fire: Small

Arms Ammunition in the Battle of Gettysburg (Gettysburg Thomas

Publications, 1991), 52-59. The three types of cannon predominantly

employed by the Army of the Potomac at Gettysburg were the Model 1857

12-lb. bronze smoothbore gun howitzers, known as "Napoleons"; the 3-inch

ordnance rifles; and the 10-lb. Parrott rifles. According to the Brig

Gen. Henry Hunt, Chief of Artillery, Army of the Potomac, of the 320

artillery pieces employed by the Union army at Gettysburg, "142 were

light 12-pounders, 106 3-inch guns, 6 20-pounders, 60 10-pounder Parrott

guns, and a battery of 4 James rifles and 2 12-pounder howitzers...."

Hunt also mentioned that his report excluded the 44 3-inch guns employed

by the Cavalry Corps' horse artillery. "Report of Brig. Gen. Henry Hunt,

U. S. Army, Chief of Artillery, Army of the Potomac, September 27,

1863." OR 27 (part 1), p. 241.

13. Patricia L. Faust, editor,

Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Civil War (New

York: Harper & Row, 1986), p. 383.

14. Miller, ed., Peninsula

Campaign, p. 184.

15. Ibid., p. 180.

16. Dabney H. Maury,

Recollections of a Virginian in the Mexican, Indian, and Civil

Wars. (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1894), pp. 53-54.

17. Miller, ed., Peninsula

Campaign, pp. 184-85.

18. George W. Cullum,

Biographical Register of Officers and Graduates of the United States

Military Academy at West Point, New York, from its Establishment in 1802

to 1890 (3rd ed., revised and extended; Boston, Houghton, Mifflin,

1891) volume 2, p. 814. "General Orders No. 185, Headquarters Army of

the Potomac, Nov. 21, 1862." U.S. War Department, War of the

Rebellion: The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies,

128 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1880-1901). series I, vol. 21, p. 785.

Hereinafter cited as OR. All references are to series I unless otherwise

noted.

19. Shrader, "Field Logistics," in

Luvass and Nelson, eds., Guide to the Battle of Antietam, pp.

260-61. The personnel authorizations apply to volunteer units.

Generally, fewer logistical personnel were authorized for Regular Army

units.

20. Thomas Weber, The Northern

Railroads in the Civil War, 1861-1865 (reprint; Westport CT:

Greenwood, 1970), p. 162.

21. Risch, Quartermaster

Support, p. 439.

22. Ingalls to Meigs, Sept. 29,

1863. OR 27 (part 1), p. 221

23. Weber, Northern

Railroads, p. 138-141.

24. S.O. No. 286, HQ of the Army.

Adjutant General's Office, Washington, D. C., June 27, 1863. OR 27 (part

3), pp. 367-68.

25. "Estimated Numbers of Wagons and

Horses, Gettysburg Battlefield Vicinity, June - July 1863." USNPS Report

(July 1993), GNMP files.

26. Cited in Hagerman, Origins of

Modern Warfare, p. 73. The figure of 93,500 is used as the strength

of the Army of the Potomac for the Battle of Gettysburg (Coddington,

Gettysburg Campaign, p. 249). 93,500 divided by 3652 (number of

wagons) equals 25.6. 1000 divided by 25.6 equals 39.06. These figures do

not include ambulances.

27. Blake A. Magner, Traveller

and Company: The Horses of Gettysburg (Gettysburg Farnsworth House

Military Impressions, 1995), p. 47.

28. Ingalls to Pleasonton, June 26,

1863. OR 27 (part 3), p. 338.

29. Ibid.

30. Brig. Gen. John Buford,

commander of the the 1st Division, Cavalry Corps, reported on June 30:

"My men and horses are fagged out. I have not been able to get any grain

yet." Buford to Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasanton, OR 27 (part 1), p. 923.

31. Meigs to Ingalls, June 28, 1863.

OR 27 (part 3), p. 378.

32. Ingalls to Meigs, June 28, 1863.

Ibid., p. 379.

33. Sawtelle to Meigs, June 28,

1863. Ibid.

34. Ingalls to Meigs, June 28, 1863.

Ibid.

35. Meigs to Ingalls, June 28, 1863.

Ibid., p. 380.

36. Ingalls to Meigs, August 28,

1864. OR 27 (part 1), p. 222.

37. Ibid., pp. 221-222.

38. Clarke to Taylor, June 30, 1863.

Records of the Commissary General of Subsistence, General

Correspondence, Letters received, 1828 - 1886. (Box 145.) National

Archives, Washington D.C. Buford's message is in OR 27 (part 1), pp.

923-24.

39. Clarke to Taylor, July 1, 1863.

Records of the Commissary General of Subsistence (Box 146.) Marching

rations consisted of hard bread, salt pork and coffee.

40. Cited in Thomas, Ready, Aim,

Fire, p. 60.

41. Flagler to Brig. Gen. James W.

Ripley, July 11863. Record Group 156, Records of the Office of the Chief

of Ordnance, General Records, Letters Received, 1812 - 1894 (box

276).

42. Weber, Northern

Railroads, pp. 164-65.

43. Ingalls to Meigs, August 28,

1864. OR 27 (part 1), p. 222.

44. Ingalls to Meigs, July 3, 1863.

OR 27 (part 3), pp. 502-503.

45. A file on Butterfield in the

Robert L. Brake Collection, USAMHI, has a note that states that a tag

was attached to a relic shell fragment. The tag reads: "While Generals

Meade, Ingalls, and Butterfield were conversing at the battle of

Gettysburg, July 3, 1863, this piece of shell from a Confederate gun

knocked down and severely wounded Major General Butterfield, Chief of

Staff of the Army of the Potomac."

46. "Report of Lieut. Cornelius

Gillett, First Connecticut Heavy Artillery, Ordnance Officer, Artillery

Reserve, Camp near Warrenton Junction, Va., August 23, 1863." Gillett

also reported that he issued 19,189 rounds from his train during the

battle. OR 27 (part 1), pp. 878-79.

47. 7th Wisconsin Infantry File,

GNMP Library.

48. Lieutenant Colonel George Woods

to Maj. Gen. David Birney, July 3, 1863. George H. Woods Papers,

USAMHI.

49. Sergeant Austin C. Stearns,

Three Years with Company K, Arthur A. Kent, ed. (Rutherford, NJ:

Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press, 1976), pp. 203-204. Stearns was in the

13th Massachusetts Infantry.

50. Russell F. Weigley,

Quartermaster General of the Union Army: A Biography of M. C.

Meigs (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959), pp. 280-282.

51. Thomas, Ready, Aim, Fire,

p. 12.

52. Flagler to Ripley, July 11,

1863. OCO, Letters Received, 1812-1894 (Box 276).

53. Hunt's Report, OR 27 (part 1),

p. 241.

54. OR 27 (part 3), p. 542.

55. Flagler to Ripley, July 6, 1863.

OCO, Letters Received, 1812-1894 (Box 276).

56. Ibid., July 11, 1863.

57. "Report of John R. Edie, Acting

Chief Ordnance Officer of the Army of the Potomac." OR 27 (part 1), pp.

225-226.

58. Gregory A. Coco, A Strange

and Blighted Land: Gettysburg: The Aftermath of a Battle (Gettysburg

Thomas Publications, 1995), pp. 318-325.

59. Ingalls to Meigs, August 28,

1864. OR 27 (part 1), p. 222.

60. Report of Surgeon Jonathan

Letterman, U. S. Army Medical Director, Army of the Potomac. OR 27 (part

1), p. 197.

61. Ingalls to Meigs, August 28,

1864. OR 27 (part 1), p. 222.

62. Ibid., p. 223-224.

63. Hagerman, Origins of Modern

Warfare, p. 76. By the end of July, some two weeks after the

campaign had ended, the supply system seemed to be back on track. In one

command, however, a few officers went to bed hungry, necessitating the

following circular order: "Many officers have complained of their

inability to procure proper food for their own use, when the troops of

their commands have been fully supplied owing to the neglect of the

Brigade Commissaries in furnishing supplies for their use at the same

time they issued rations to the men. Officers are human as well as

enlisted men and have natural wants and the duty of Brigade

Commissaries attends to supplying officers as well as men." Circular of

the 2nd Division, III Corps, dated July 29, 1863. George H. Woods

Papers, USAMHI. (Emphasis added.)

64. Hagerman, Origins of Modern

Warfare, p. 77. The breakdown was as follows: 6 wagons for baggage,

7 wagons for subsistence and quartermaster supplies, 5 wagons for

ordnance, and 2 wagons for medical supplies.

65. Miller, "Federal Logistics," in

Miller, ed., The Peninsula Campaign, p. 185; Francis B. Heitman,

Historical Register and Dictionary of the United States Army, from

its Organization, September 29, 1789, to March 2, 1903 (reprint;

Univ. of Illinois Press, 1965) vol. 1, p. 307.

66. Heitman, Historical

Register, p. 424; Ordnance Hall of Fame file, U. S. Army Ordnance

Museum, U. S. Army Ordnance Center & School, Aberdeen Proving

Ground, MD; Cullum, Register of Graduates, vol. 2, p. 814.

67. Heitman, Historical

Register, p. 562; Miller, "Federal Logistics," in Miller, ed.,

The Peninsula Campaign, p. 180.

|

|